What are central banks for? How should they be governed? What is their role in the 21st century?

The recent German Constitutional Court decision has forced all these issue to the forefront of political debate. As I lay out, at length, in this piece for Foreign Policy, the judicial battle in Germany is more than a storm in a European tea-cup. It brings to the fore basic questions of modern governance that have implications far beyond Europe.

This is a problem of economics and politics, but also of history.

As I argue in the Foreign Policy piece, we still live under the shadow of the conservative reaction to the last inflationary surge in the world economy in the 1970s – the so-called “great inflation”.

I’ve long been interested in the way the 1970s figure in history – growing up between West Germany and the Uk at the time, you could hardly not be!

In the early 2000s I taught a class in Cambridge called “After the Boom” that dealt with the various strands of social theory that emerged from the late 1960s.

Political economy was definitely on my mind then. But it was after 2013 that I really began to get seriously interested in the problem of inflation/deflation and the legacy of the 1970s.

In this blog post, in an effort at integration, I have pulled together a variety of different pieces, papers and talks I have given since 2013 on the question of the central banks and inflation. This lays out the background to the piece in Foreign Policy, but also to Crashed and to my debate with the German sociologist Wolfgang Streeck in the pages of the LRB. They are contributions to a historical politics of monetary policy.

Why did my interest begin to focus on central banks and inflation in 2013?

On the personal side I finished the manuscript of Deluge that summer and I was going through some major upheaval. In the wider world it was the phase of the most intense arguments in Europe over austerity. In intellectual terms Wolfgang Streeck published Gekaufte Zeit (Buying Time 2014 english edition), his Adorno lectures, which were positioned as a resumption of a brand of German crisis theory that culminated in the 1970s with Habermas’s Legitimation Crisis.

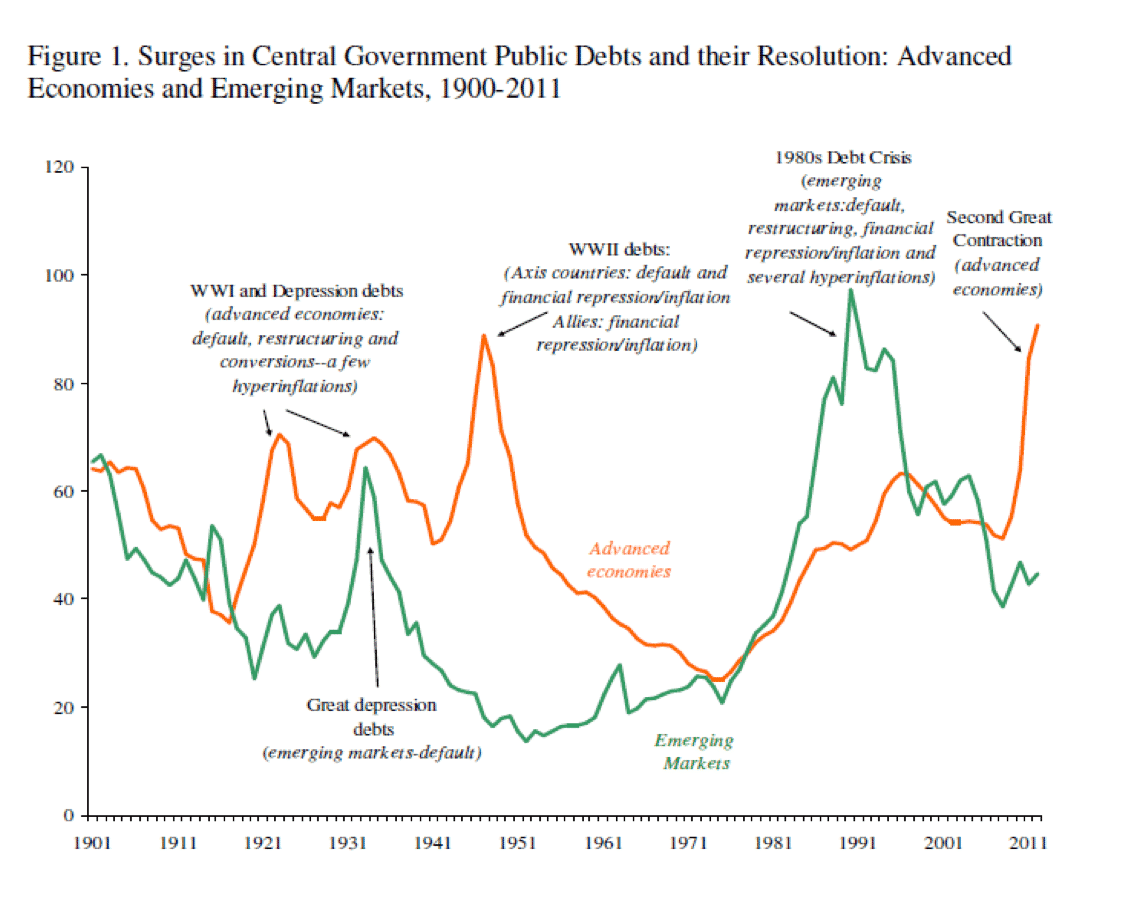

In 2013 the politics of debt were the key issue. Historically, inflation has been the solution to debt. it had been key to the working off of debts after World War II across the developed world.

In 2013 it was ruled out.

If austerity was the hammer then anti-inflationary central banking was the anvil. The two had been brought together in the 1970s. Streeck’s purportedly radical, but to my mind conservative theorizing of our contemporary condition, actually incorporated key assumptions of that conservative 1970s synthesis.

My hunch was that a progressive politics needed to overcome that reading of the 1970s. This was at one and the same time a normative/political position, a historiographical position and an observation about the realities of central banking post-2008. It seemed to me that the practitioners of modern central banking were further along than radical theory.

As I got deeper and deeper into the research for Crashed I became more and more impressed by the de facto radicalism of 21st-century economic policy and policy-economics, in the BIS-mould.

My first foray into the advocacy of a pro-flationary progressivism/monetary populism was an inflationist manifesto in the Sueddeutsche Zeitung:

Tooze Sueddeutsche Zeitung 2013 Inflation gegen die Krise – Mehr Geld! – Wirtschaft – Süddeutsche

This culminated in the the deliberately provocative riff on Horkheimer.

Horkheimer had famously said that “whoever wishes not to speak of capitalism, should also remain silent about fascism.” My inflationist variant was “Whoever wishes not to speak of inflationary distributional struggles, should also remain silent about debt jubilees and a new politics of equality”.

I gave an English version of the argument at Columbia in the fall of 2013 under the title “Who is Afraid of Inflation?”. Powerpoint slides here:

tooze who is afraid of inflation september 2013

My hook was that in 1972 Helmut Schmidt, the notoriously centrist SPD Finance minister and later Chancellor, had been less worried about inflation than radicals seemed to be in the 21st century. What had happened?

Meanwhile, I was asked to contribute a critique of Streeck’s Gekaufte Zeit as part of a forum in the Journal of Modern European History 12 (2014), which culminated in an essay, which lays out my arguments against his position on the Eurozone, inflation and the very idea of “buying time”:

Tooze on Streeck Who is afraid of inflation?

Streeck responded to me and the other contributors in that same journal.

Behind Streeck was an even more basic reference point in the political economy literature: the famous volume edited by Fred Hirsch and John H. Goldthorpe in 1978 on the political economy of inflation.

This volume mattered not only for the field of political economy but also for the historiography of the early 20th century. Charles Maier was a contributor to the Hirsch and Goldthorpe volume. Maier’s classic Recasting bourgeois Europe had appeared three years earlier in 1975, a text I had been wrestling with in Deluge. Gerald Feldman and others were at the same time, in the 1970s, beginning to rewrite the history of the Weimar hyperinflation.

In my head, by way of Deluge (about 1916-1931 in dialogue with Maier and Feldman) and Crashed (about 2008-2018 in dialogue with Streeck (who was himself extending the argument of Goldthorpe and Hirsch, (shot through with echoes of the 1920s by way of Maier))), the worlds of 1914-1931, the 1970s and the era after 2008 – were all resonating with one another.

Out of this maelstrom emerged a short, unpublished and somewhat delirious piece given as a paper at a conference organized by my old friend James Thompson at Bristol. In the paper I attempt to make a science-studies, “symmetry” type move on the Goldthorpe interpretation of the political economy of inflation.

To do so, I pit Goldthorpe against Robert Lucas’s famous critique of the possibility of modeling optimal macroeconomic policy.

Text Tooze Inflation Calculations Goldthorpe and Lucas. Slides Bristol Tooze presentation.

If nothing else, that short piece enabled me to find some distance to the influential Goldthorpe model.

Together with Stefan Eich, I then sketched a new reading of the politics of inflation in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Our argument was that the standard historiography of the conquest of the great inflation was itself a product of the triumphalism of the Great Moderation and that had been put fundamentally in question by 2008. In light of that crisis it was time to revisit the politics of the 1970s “and to pose the question put to modernity by Alexander Kluge. Was the refoundation of democratic capitalism through the overcoming of inflation a learning process with a fatal outcome?”

As we argue:

“The aim of our anti-heroic narrative of disinflation is not, however, simply to suggest a revision of the familiar view of the Thatcher and Reagan »revolutions«.The aim is to revise our understanding of the problem of democracy in relationto economic policy. Left- and right-structuralists postulate a conflict between democracy and capitalism, which, on the left reading, must either lead to terminal crisis, or in the right-structuralist version must be overcome by depoliticization.That is the moral drawn from the history of inflation in the 1970s and the1980s. Inflation was a political and economic time bomb that had to be defused as urgently as possible. A critique of both positions by way of a new history of the struggle over inflation in the 1970s, would, by contrast, seek to disarm this rhetoric of emergency and necessity. What we must insist upon is that under conditions of a fiat money regime, the choice of deflation or inflation is open. The problem is not that of a lethal and urgent menace to the common good. It is thatof a political choice with distributional consequences. The historical question is how that openness became foreclosed and how the history of that closure has been told. Depicting the history of the 1970s as a choice between a populist and delusionary »sell out« to inflation, and the virtue and realism of disinflation, is the beginning of that closure.”

I really wish that this essay with Stefan was more widely read. To that end I have put it here for download: The_Great_Inflation_w_Adam_Tooze_2016

After the exchange with Streeck in the pages of the LRB I returned to the question of central banking politics and our understanding of financial globalization in this piece with Danilo Scholz in Merkur.

Scholz Tooze Merkur Mai 2017 korr

Unfortunately, it is in German, but it may be of interest for that audience.

The title is excellent – “For a politics of monetary policy”.

Danilo and I insist that it is both compelling and reasonable to ask the question – what should a democratic monetary policy look like? It is necessary because monetary policy is a comprehensive and key domain of power. It is reasonable because politicizing monetary policy is not by itself a recipe for disaster.

Indeed as the eurozone demonstrates, we cannot escape the politicization of monetary policy, whether we like it or not.

The implication of this position is that central bankers were politicians. So I was more supportive than some of the choice of Christine Lagarde as the successor to Draghi at the ECB.

Given the persistence of mass unemployment in the Eurozone, inspired by recent American histories of economic policy debates in the 1970s, I went on to argue in this piece in Social Europe that the ECB, like the Fed, should have a dual mandate.

When the debate began in 2019 about the Green New Deal I argued in the pages of Foreign Policy that central banks had a key role to play. That attracted the attention of the Bundesbank and Jens Weidmann to whom I responded. The original provocation and the riposte can be downloaded here:

Why Central Banks Need to Step Up on Global Warming – Foreign Policy

Jens Weidmann and the German Central Bank Are Giving Climate Change a Pass

Meanwhile, in the battles between Donald Trump and Jerome Powell the politics of central banking were heating up in the US as well. This culminated in August 2019 with Bill Dudley, former President of the New York Fed, arguing on the pages of Bloomberg that the US central bank should join the resistance to the Trump Presidency.

At the same time in the pages of the European media, a more or less open campaign of intimidation was waged by ex-Bundesbanker against Mario Draghi and his successor.

Against that backdrop I was invited to talk at the New York Fed about the role of central banks in 20th century history.

Tooze NY Fed Oct 2019 compressed

That led to an invitation to a World Bank conference on central banking in Beijing where I sharpened and reiterated the argument on the need to find a new political definition of the role of central banks.

Tooze Populism and central banks Beijing Dec 2019 compressed

To the central bankers my point was: The world is knocking on the door! Whether you like it or not you are being sucked into political fights. Should central bankers retreat and try to defend the remit of “independence” & simple macroeconomic mandates? Or should you seek new fields through which to legitimate yourselves?

As I end by arguing in the Foreign Policy piece:

It is time to step out of the historical shadows left by the 1970s. Doing so is no doubt hedged with risks. But so too is attempting to patch and mend our anachronistic status quo. Half a century on from the collapse of Bretton Woods and the emergence of a fiat money world, 20 years since the beginning of the euro, it is time to give our financial and monetary system a new constitutional purpose.