Politicized memory plays strange tricks. To listen to influential Western voices in 2023 you might imagine that China emerged in December 2022 from long confinement in a zero-COVID prison, a regime dictated by the vanity of Xi Jinping, a regime which inflicted years of comprehensive and repressive lockdowns on a hapless population and revealed the threat posed by the unfettered power of the CCP.

This is how Adam Posen begins his much-discussed Foreign Affairs article:

After three years of stringent restrictions on movement, mandatory mass testing, and interminable lockdowns, the Chinese government had suddenly decided to abandon its “zero COVID” policy, which had suppressed demand, hampered manufacturing, roiled supply lines, and produced the most significant slowdown that the country’s economy had seen since pro-market reforms began in the late 1970s.

Source: Foreign Affairs

Listening to the Checks and Balances pod from the Economist I heard a contributor casually remark, “for 2 years China stifled its economy with zero Covid”, or words to that effect.

This is, to say the least, an audacious rewriting of history and reflects the way events that took place as recently as 18 months ago are subject to reinterpretation in light of the new, overwhelmingly negative narrative.

***

The idea of zero-covid as a policy of sustained repression conforms to Western preconceptions about Xi’s regime. And it is true that between 2020 and 2023 it was hard for anyone from outside to visit China. It is also true that the Shanghai lockdown in the spring of 2022 was draconian and that in the second half of 2022 increasingly unpredictable and radical measures were taken across China. The most extraordinary of all were the “closed-loop” factories operating under inhuman quarantine conditions.

It is undeniable that by December 2022 Xi Jinping’s regime was forced into a humiliating climb down, accompanied by significant economic damage, a collapse in confidence, unprecedented streets protests and, over the winter of 2022-2023, a large-scale loss of life. But this is not a story of “the last three years”, stretching back to the original lockdowns in China in January and February 2020. For much of 2020 and 2021 the successs of zero-covid meant that China’s pandemic containment on the ground was less repressive than in many parts of the West. It was the Omicron mutation that turned a highly successful policy into a fiasco. Many will remember the scenes of partying in Wuhan in the summer of 2020.

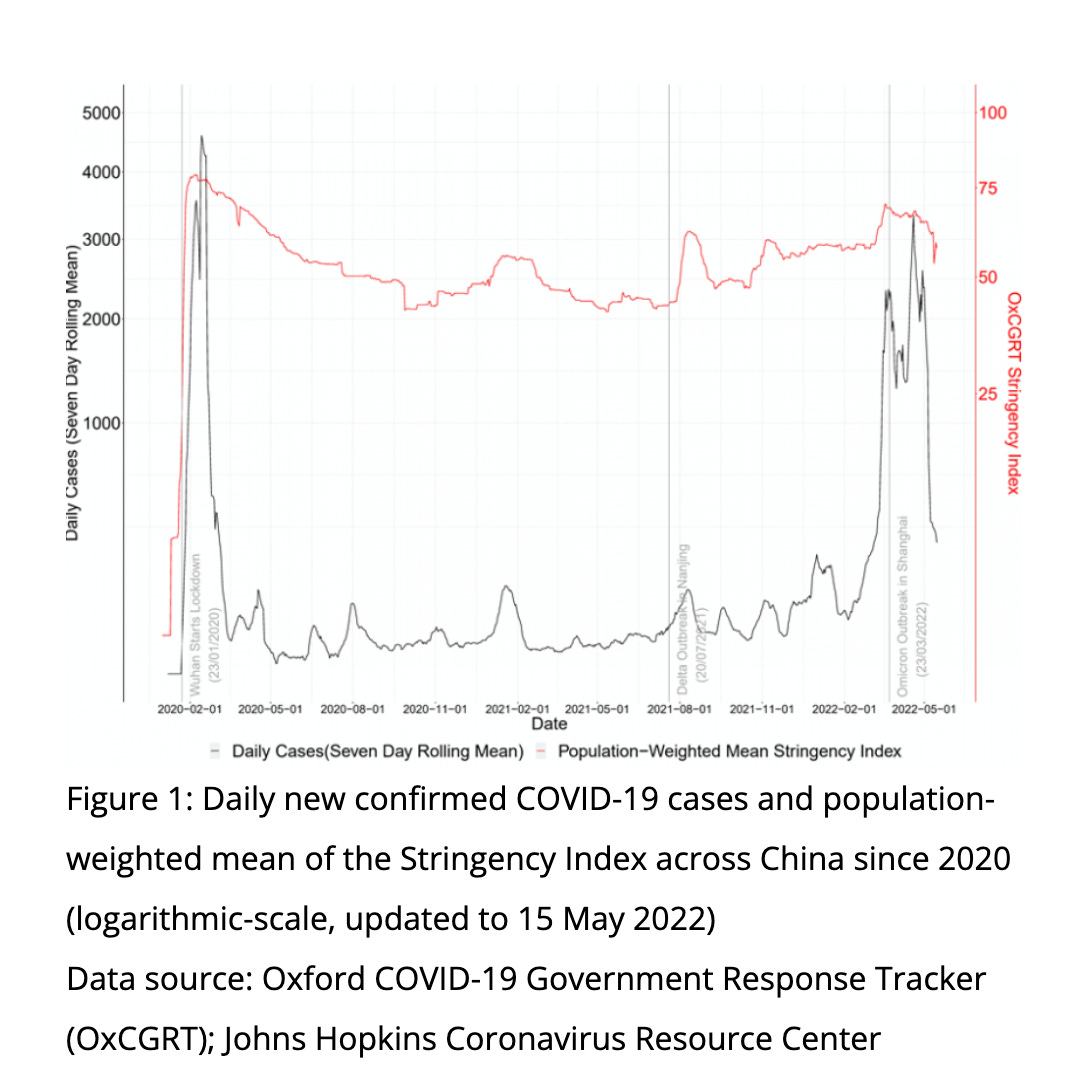

If you consult standard COVID response trackers you can see the way in which stringency in China varied over time.

Source: Hale et al 2022

This was the logic of what became known as the “dynamic clearing” model which operated successfully in 2021. As Gavekal explained:

Although often referred to as a “zero-Covid” strategy, dynamic clearing was actually adopted after it became clear that it was no longer possible to keep new case numbers at zero. The goal was instead to ensure that case numbers were at least heading to zero in every locality with an outbreak. As long as each outbreak is relatively isolated, it can be contained by restrictions in only the affected area, limiting the disruption and allowing the government to concentrate attention and resources where they are most needed.

It is easy to conflate the on-off quality of dynamic clearing with the original sin of unfettered CCP authority. But actually it followed a short sharp shock logic of pandemic containment. It was uncomfortable to live with, but was not arbitrary. And in 2021 it was highly successful allowing Delta to be stamped out.

Faced with Omicron it was clear that there would be bigger problems. Discussions about lifting restrictions began in earnest in Beijing at the end of 2021 and as early as March 2022, top medical experts submitted a detailed reopening strategy to the State Council, China’s cabinet. But before steps could be taken Omicron arrived in Shanghai and without a tried and tested alternative on hand, the authorities responded in familiar style with a massive and comprehensive lockdown.

In 2021 in Shanghai the anti-Delta measures had offered a reasonable trade off. In 2022 the lockdown was much longer and more damaging in its impact.

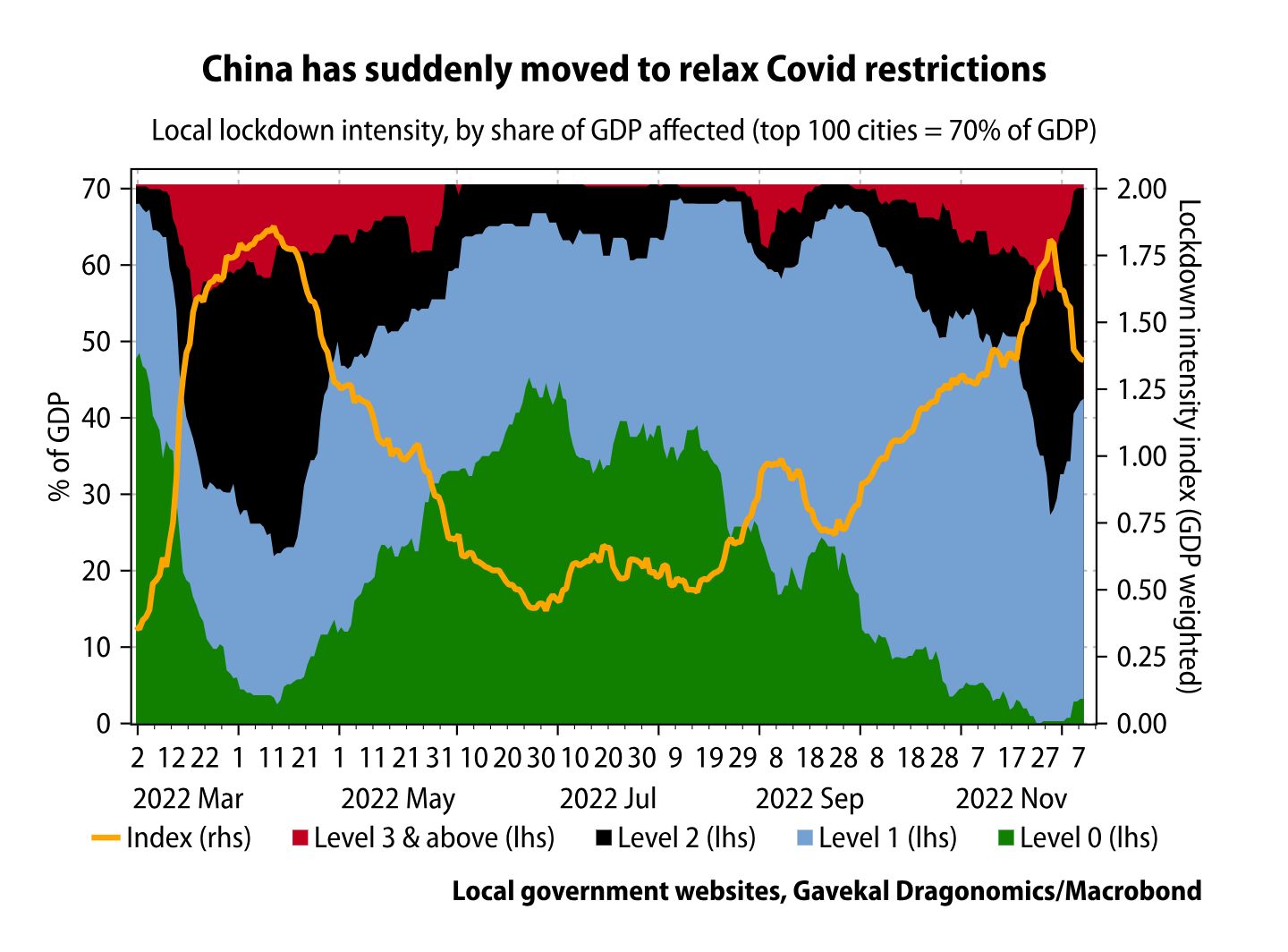

But even in 2022 it is a myth to claim that zero COVID required blanket application of lockdowns. According to the Gavekal tracker, in June 2022 cities acounting for 40 percent of GDP had abandoned all lockdown measures and two thirds of the Chinese economy was under Level 1 or below. This was the strategy of dynamic clearance in operation: not blanket and endless lockdowns, but tactical decisions taken on a case by case basis to stamp out local outbreaks, followed by quick reversal.

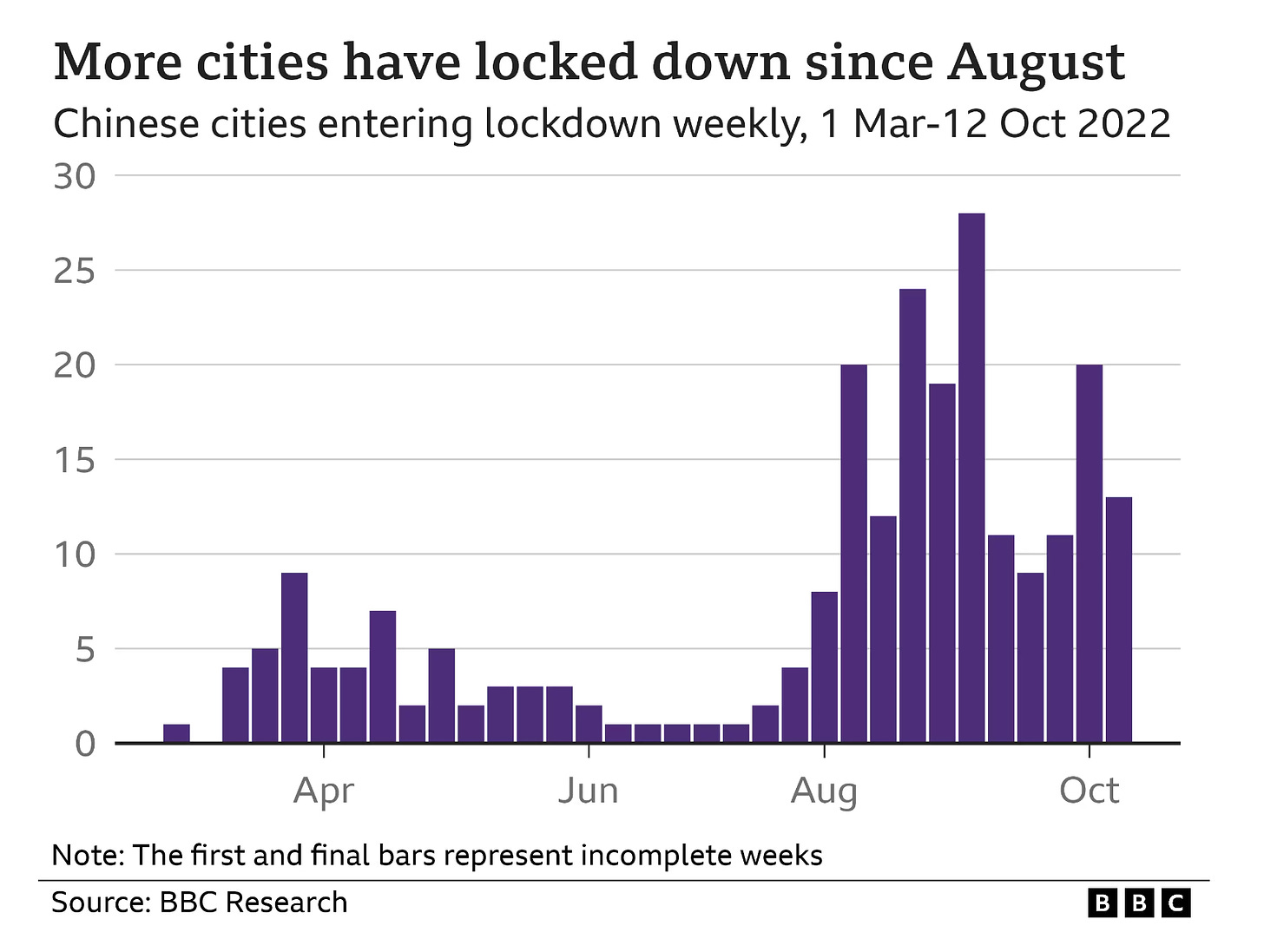

Over the summer, having achieved clearance, Shanghai relaxed. But the Omicron infection now spread to several other cities that did not have Shanghai’s resources. Notably in the Western provinces, containment began to breakdown. Within a matter of weeks Beijing lost control. As the decisive 20th Party Congress approached in October, for the first time since the pandemic began, Omicron was running rampant across the country.

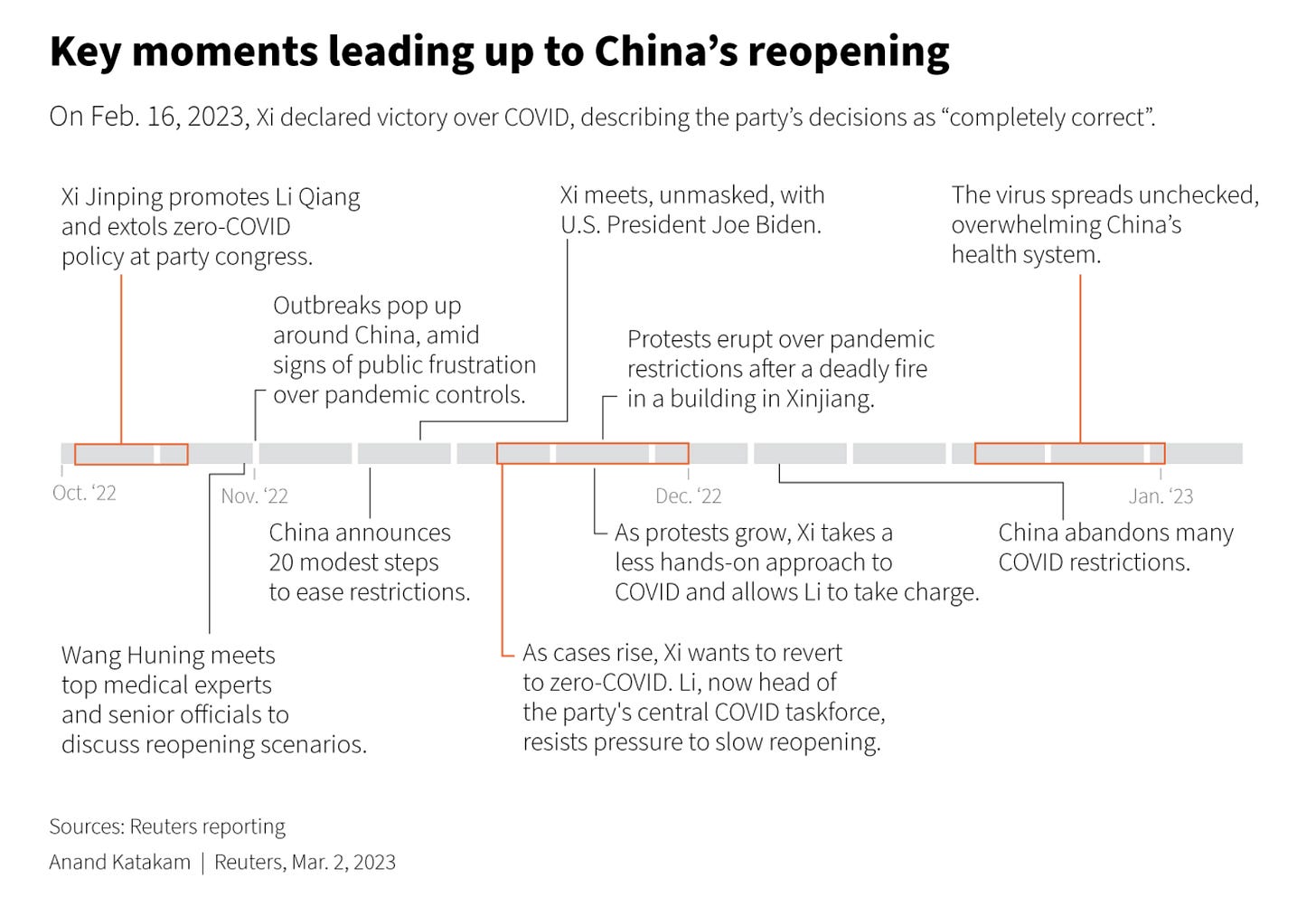

Xi’s timeline was dominated by the Party Congress in mid-October. As soon as that was over, the debate about the future of zero Covid began in earnest. Leading health experts like Wu Zunyou, China’s CDC chief epidemiologist, called on October 28 for measures to be relaxed, criticizing Beijing city government for draconian controls that had “no scientific basis.” He scolded the municipality for a “distortion” of the central government’s zero-COVID policy, which risked “intensifying public sentiment and causing social dissatisfaction.”

In early November, then-Vice Premier Sun Chunlan, China’s top “COVID czar,” summoned experts from sectors including health, travel and the economy to discuss adjusting Beijing’s virus policies. This resulted in Xi’s orders on November 10 to adopt 20 new measures to optimize the policy response, including tweaking restrictions, such as reclassifying risk zones and reducing quarantine times.

These efforts to optimize policy only added confusion. The effort to liberalize, ironically, made decisions at every level of government, less not more predictable. This is how Gavekal’s researchers described the breakdown of control in the autumn of 2022:

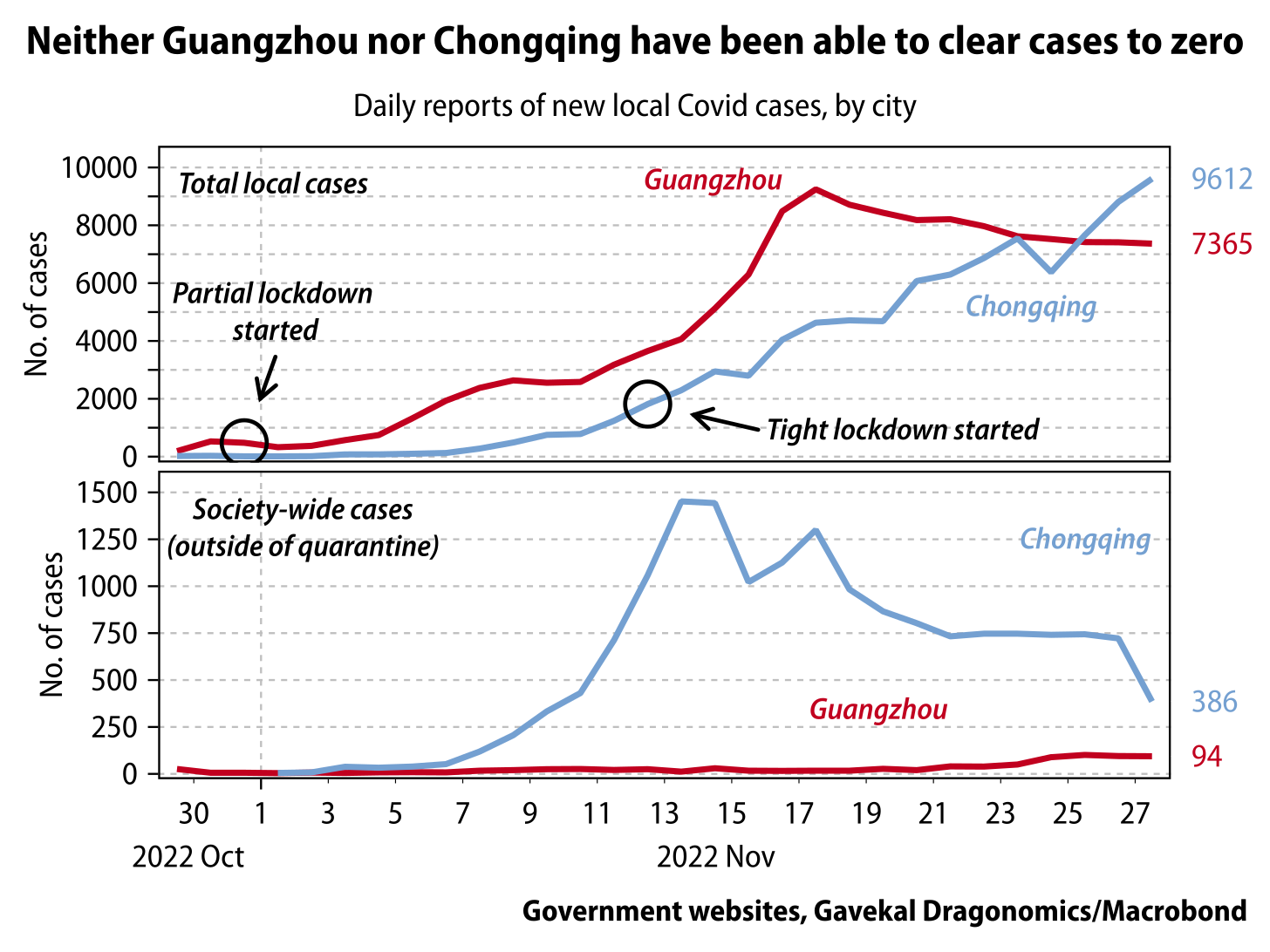

The central government tried to correct the problem by announcing 20 measures to “optimize” Covid policy, which aimed to limit the administrative and fiscal burden on local governments and thus allow them to concentrate more effectively on the necessary measures to contain the virus. But the reception and interpretation of these optimization measures was confused, with several cities relaxing their Covid restrictions even as case numbers spiraled. Those decisions allowed outbreaks to become even larger and more widespread, and thus increasingly difficult to control. By last week, many cities had reversed course after the “optimized” measures failed to slow the spread. Two cities whose loose approach to Covid controls drew nationwide attention, Shijiazhuang and Zhengzhou, both re-imposed tough lockdowns as their outbreaks spiraled out of control. And many other large cities that had been trying to manage with only targeted restrictions have gotten more aggressive: Chengdu and Tianjin have both imposed city-wide restrictions on retail services over the past few days, and expanded residential lockdowns to wider areas. … Covid restrictions began to sharply intensify around November 19, just a week after the first announcement of the optimized policies. These reversals—which seemed to go against the central government’s promise of less invasive Covid controls—were the context for the sizable protests that broke out starting November 25. Local governments were already reluctant to use aggressive measures to contain Covid transmission, and will be even more so now as they will try to avoid direct confrontations with the public … Urumqi, where the protests began, quickly announced a partial reopening of public transportation and businesses even though it has not gotten new cases fully under control after more than three months of lockdown. In Beijing, where there were also many protests over the weekend, the local government has relaxed restrictions in several areas even though case numbers are still high. But the experience of Urumqi and other large cities struggling to contain outbreaks suggests that the “dynamic clearing” approach was already breaking down even before the protests, for a couple of reasons. … Now, outbreaks are no longer isolated, which increases the strain on government capacity and makes every outbreak harder to control. As of November 27, 306 of China’s cities, over 85% of the total cities that directly report such data, were reporting new Covid cases, the highest figure on record and twice the level before the “optimization” of policy. Targeted restrictions on individual buildings and neighborhoods, the optimized strategy envisioned by the central government, are extremely unlikely to be consistently effective in this environment.

Throughout November the debate raged about how to proceed. Xi’s preference, apparently, was to crackdown with ever greater force. But the telling point is that Xi did not get his way. Fresh from the Shanghai battlefield, the new #2 Li Qiang insisted that the costs were too high. The economy was clearly suffering. Protestors made the point loud and clear.

At the city level the resources for implementing tough testing and quarantine regimes were running out. As Reuters reported:

A local leader of a sub-district in Beijing with over 100,000 residents told Reuters that by the second half of last year it had run out of money to pay testing companies and security firms to enforce restrictions. “From my perspective, it’s not that we set out to relax the zero-COVID policy, it’s more that we at the local level were simply not able to enforce the zero-COVID policy anymore,” the official said. Beijing’s local government, which did not respond to a request for comment, spent nearly 30 billion yuan ($4.35 billion) on COVID prevention and controls last year, official data show.

At the G20 in Bali on November 14 during his meetings with Biden and Trudeau Xi showed himself without a mask. But at home he continue to take a hard line, demanding the “unswerving” execution of zero-COVID. But that was increasingly unrealistic. And as Li repeatedly emphasized the economics costs were mounting up. In meetings with Xi on November 19 after his return from the G20 trip, Li resisted Xi’s pressure to react to ever worse infection numbers by slowing the pace of reopening.

By the end of November it was clear that the outbreak in the two megacities of Guangzhou and Chongqing could no longer be contained. Both cities had adopted aggressive lockdown strategies but the case load was no longer reacting.

Rather than following Xi’s preference, or the more gradual timeline preferred by health experts, the decision was taken to accept the price in terms of life and to announce a complete end to all measures in early December.

It is hard to see how you turn this narrative into one of pigheaded and arbitrary repression. It is far more plausible to see it as an effort first at dynamic clearing and then optimization, an effort to minimize the impact on society and economy, which was successful in 2021 but failed when faced with Omicron. This exposed the limitations of local government resulting in an increasingly haphazard and incoherent policy. Once the failure was apparent, within a matter of weeks, despite the reputational cost, the repressive impulses of Xi were overruled and the regime opted to prioritize public order and economic recovery.

***

Of course, the pandemic period saw huge global economic uncertainty. But even in 2020 the regime was highly sensitive to the need to maintain production. And by the summer of 2020 the Chinese economy stood out globally precisely for the strength of its rebound from the first COVID shock.

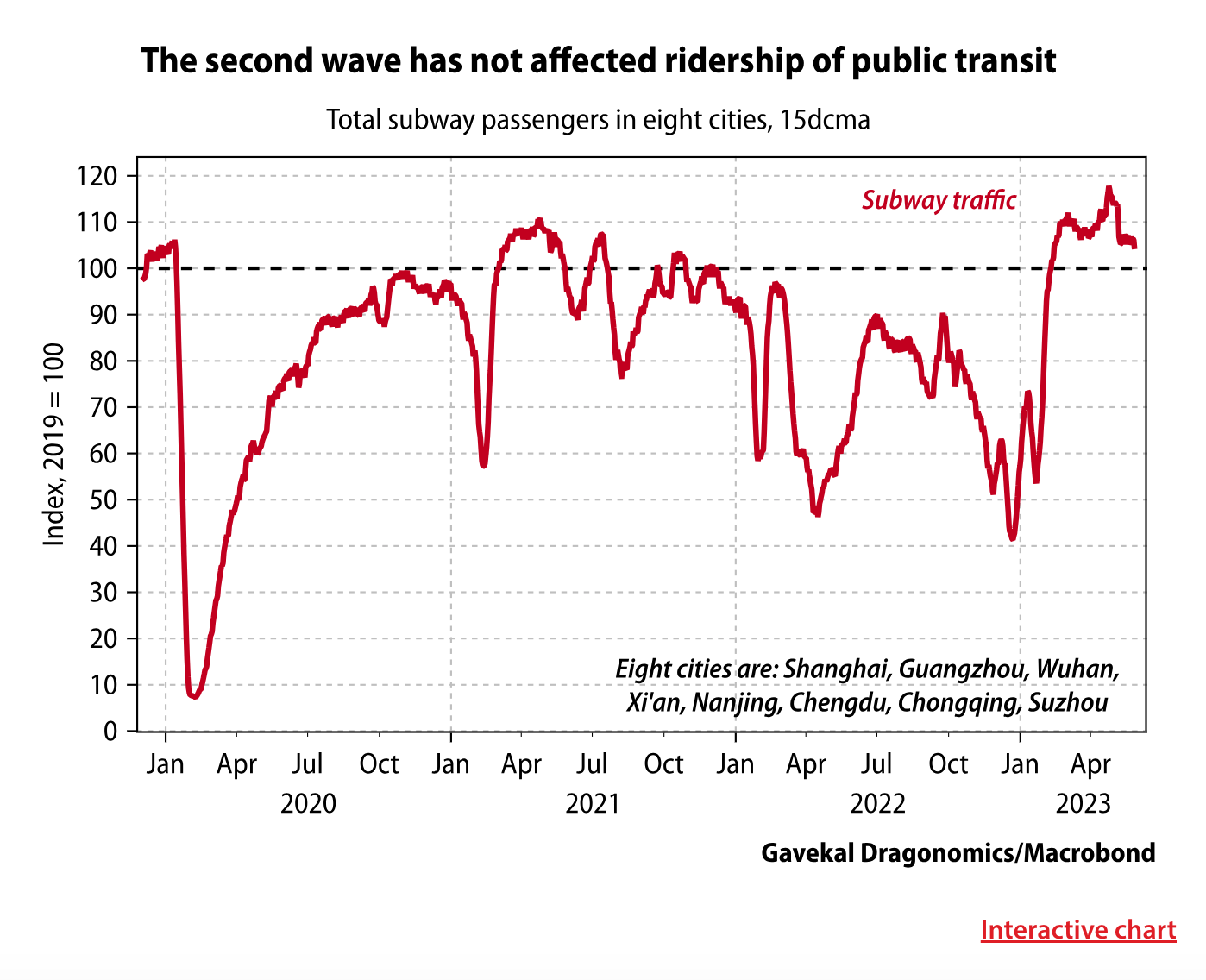

From the last quarter of 2020 throug the end of 2021 subway ridership in Chinese citie was normal 2019 levels. No sign of any lockdown.

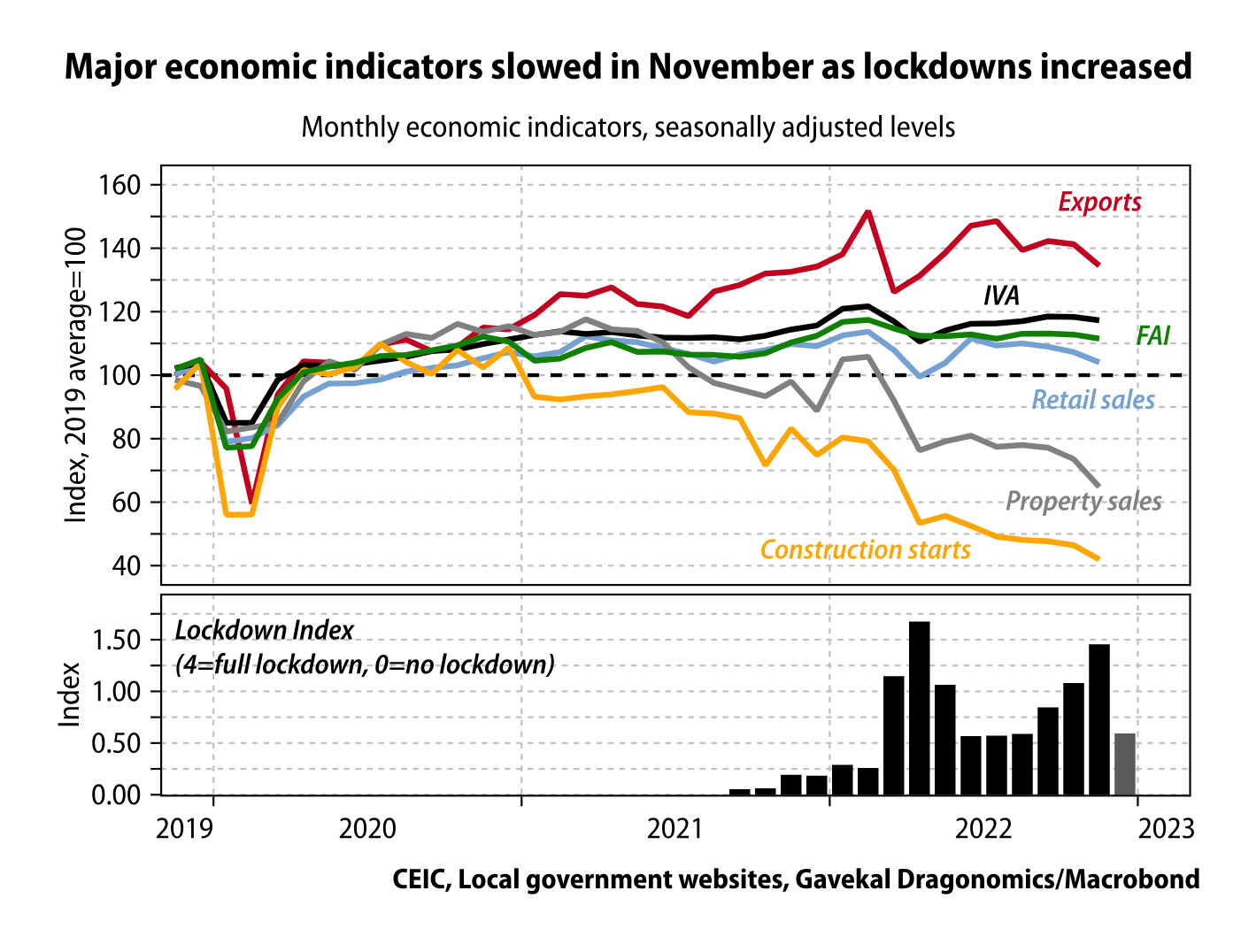

Rather than being consumed by emergency measures, as in Europe and the US, it was the success of zero COVID that set the stage for the regime to take a series of fateful strategic decisions on Hong Kong, tech platforms and housing, which betokened its sense of control and dominance. The trajectory of the Chinese economy in 2020 and 2021 was dominated not by a general downturn driven by zero-COVID but by the divergent forces on the one hand of booming exports driven by a huge surge in global demand and by the deflationary effect of pricking the housing bubble.

Source: Gavekal

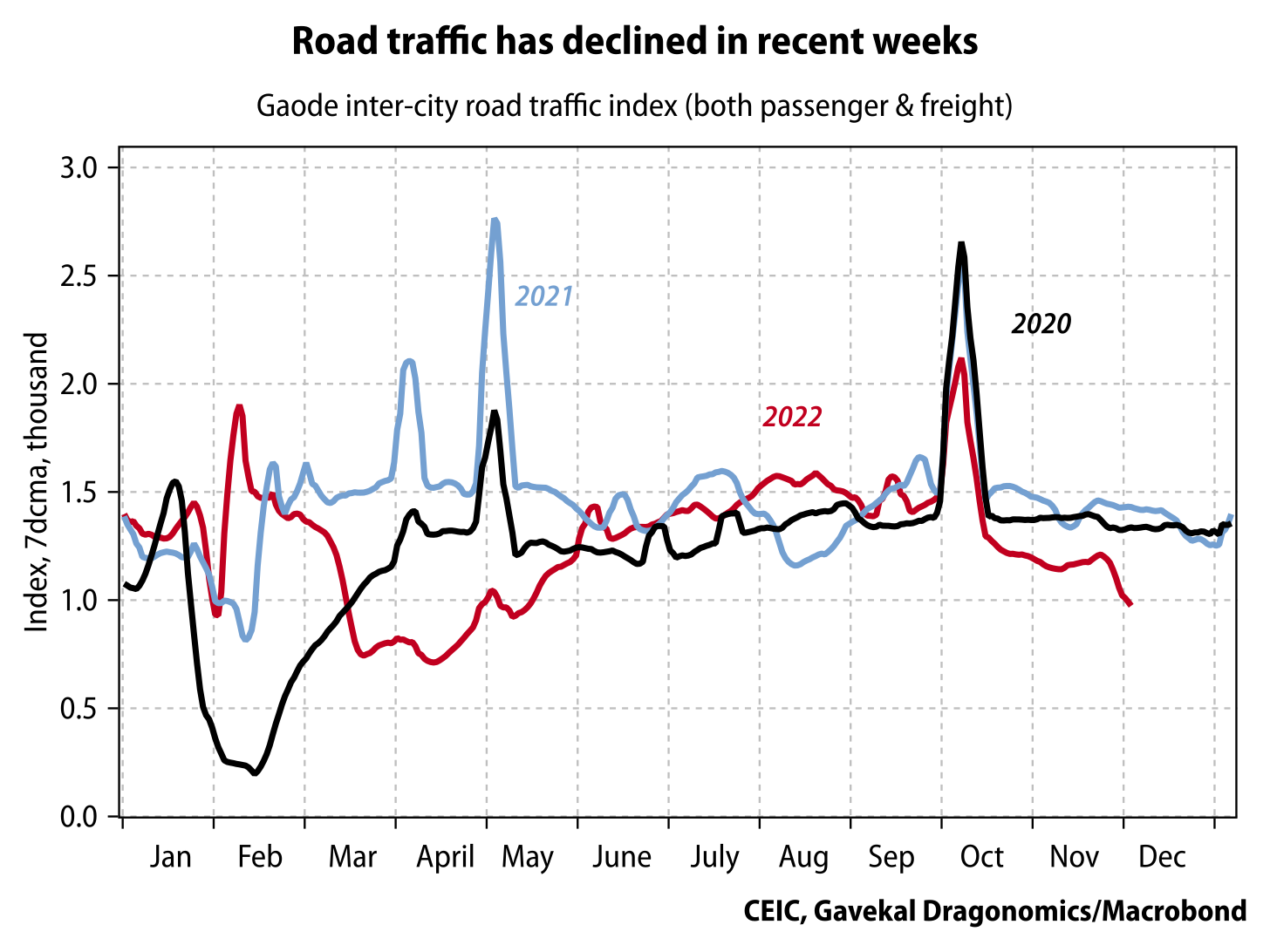

The impact of the Omicron lockdowns in 2022 was doubly damaging, threatening to disrupt the export supply chains and to intensify the depressed mood in the housing market. But the basic pattern of China’s economic development was set by exports and housing and not by the debacle of COVID policy. The road traffic index shows a significant slowdown in March and April 2022 which reflects the Shanghai lockdown. But from June until October it closely tracked previous years. Only in October did the new wave of lockdowns begin to bite in earnest.

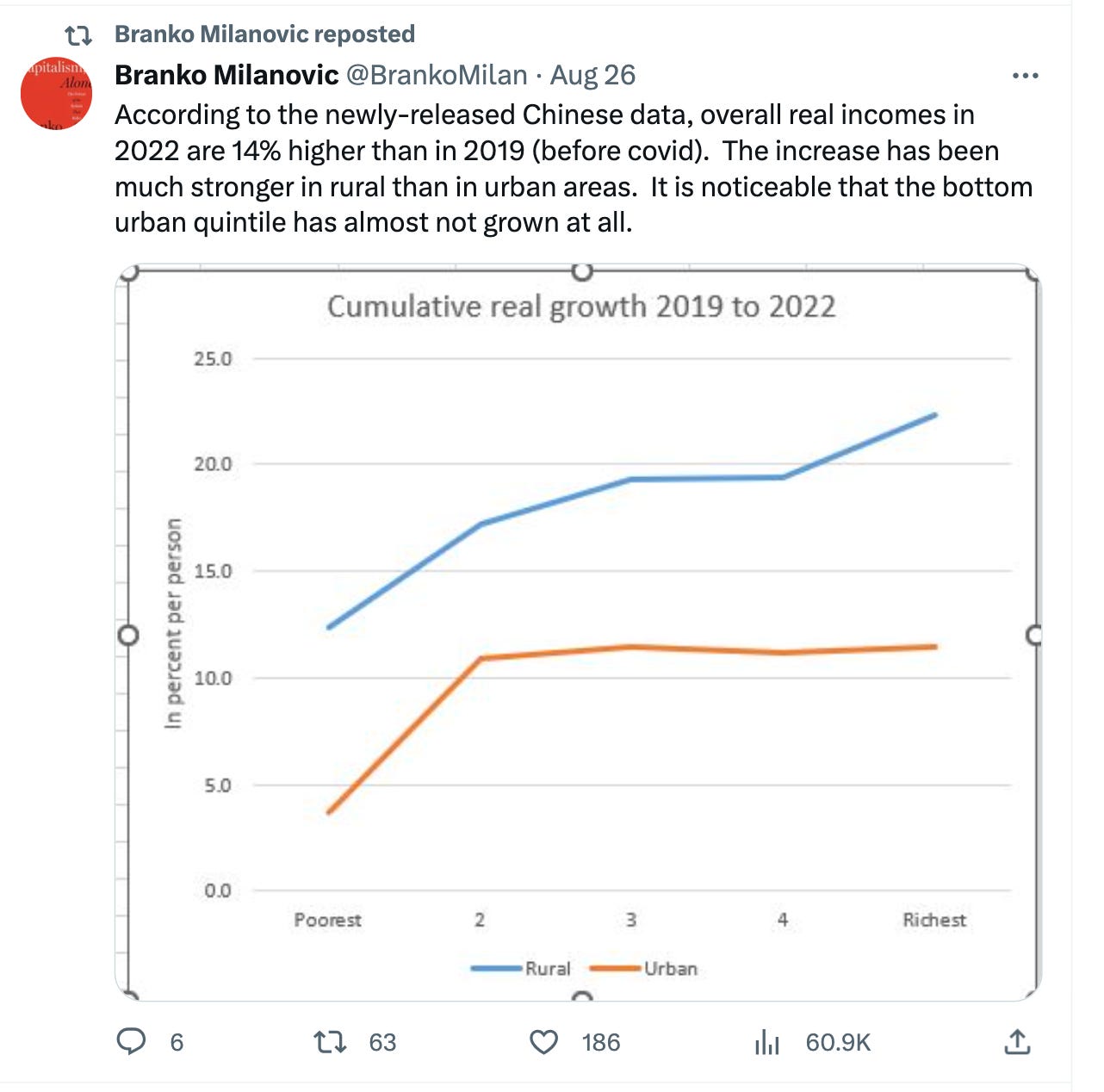

If you look at overall growth data for the period 2019 to 2023 as Branko Milanovic recently did in the course of inequality research you see the following

The impact of successive shocks on low-income workers in cities is clear from the data. But so is sustained progress overall. If these data are to be believed they give the lie to idea of 3 years of stagnation.

***

Up to 2022 the ultimate vindication of China’s zero covid policy was that it had saved lives. The contrast in mortality between China and much of the rest of the world was spectacular. The regime’s prestige was tied up with that success. That was galling for the rest of the world, but hardly surprising. Imagine, for a second, the boasting, if the United States had been able to claim a similar record.

It didn’t last. But the incoherence of the regime’s eventual pivot is hardly remarkable . There isn’t a political system in the world that can claim to have followed a policy towards COVID that was coherent or able to track the twist and turns of the virus. What is remarkable about the Chinese trajectory are not its contradictions, so much as the suddenness of the pivot and its completeness. That was presumably a mixture of both panic and calculation. If you are going to abandon Zero Covid you might as well reap the full benefits in economic terms.

It is clear that Beijing was fully aware that this change of policy would cost lives and weighed that seriously. In meetings in October and November, Wang Huning, deputy head of the party’s central COVID taskforce since early 2020 and a member of China’s elite seven-man Politburo Standing Committee, repeatedly asked for estimates of how many people would die if zero COVID were abandoned. On that basis different timelines were prepared for the eventual exit.

We are unlikely ever to know the eventual death toll from the sudden abandonment of zero COVID. No good records have been published. But the forecasts were that between 1.3 and 2.1 million, mainly elderly Chinese would likely die. One recent studyusing proxies like Baidu searches suggests a figure of 1.87 million excess deaths over the winter of 2022-2023. That is a final horrifying addition to the global COVID death toll. Placed in relation to population it means that China eventually found itself with a middling mortality, with roughly half the number of dead in proportional terms than in the USA.

It is a sign of the times that this sad, but in the end rather familiar story should be interpreted as an expression of the peculiar dysfunctions of China’s regime.

**

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.