(The) Ouroboros, (is) a mythical animal which swallows itself, starting with the tail. It epitomises paradox and is a pretty good emblem for US banking at the moment. Autocannibalism is not something anyone should try at home.

What a great passage from Jonathan Guthrie in the FT last week!

But is American capitalism best thought of as engaged in autocannibalism, or does it more closely resemble an unbalanced Darwinian competition with one giant apex predator? A predator that is taking advantage of the harsher living conditions for many of its smaller competitors and thus permanently changing the “game”.

***

A reversal of monetary regime like the one we have seen in the last 18 months creates stress and risk for the weakest financial institutions. But it also open opportunities for accumulation and creative destruction. The way key players exploit those possibilities reshuffles the economic and political pack. That in turn shapes what comes to be seen as “structure”, or the “order of things”.

In the financial crisis of 2008 there were two big winners. One was BlackRock, which, as I discussed in Chartbook #82, emerged from the GFC as the dominant asset manager of the following decade. In banking, if there was a big winner in 2008, it was JP Morgan. JP Morgan’s leadership came to regret the terms of their acquisitions during the crisis. As the ultimate owners of Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual JPMC was exposed to huge liabilities. But the deals helped to consolidate JP Morgan’s position both in retail and investment banking.

In the crises triggered by the Fed’s rate hiking cycle in early 2023, it is again JP Morgan Chase that is the dominant player.

- What makes JP Morgan Chase stronger than other banks in the U.S. financial system?

- What is the nature of its relationship with the U.S. government?

- Could CEO Jamie Dimon’s political influence extend to electoral politics?

Cameron Abadi and I discuss all these questions on the Ones and Tooze Podcast this week. Click here for the links.

***

The immediate cause for all our focus on JP Morgan and its CEO Jamie Dimon is that having led the private-sector effort to stabilize First Republic bank, JP Morgan emerged from a frantic weekend of bargaining with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as the only bank that was able and willing to absorb First Republic lock stock and barrel. The FT report on the negotiations by James Politi, Colby Smith, James Fontanella-Kahn, Stephen Gandel and Brooke Masters brings this out brilliantly.

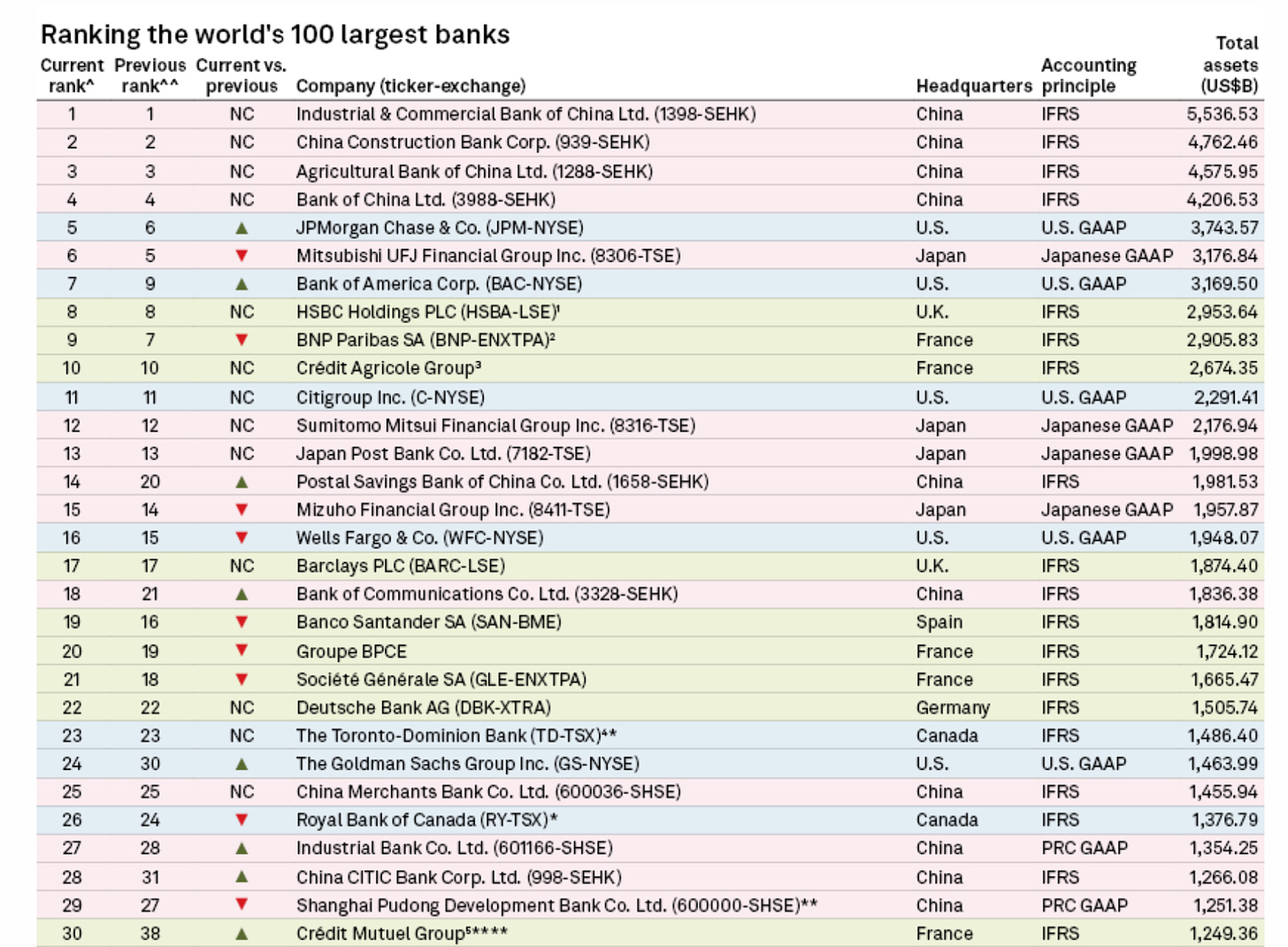

The events of the last few months confirm the fact that JP Morgan Chase now stands head and shoulders above all the other major American banks. Indeed, it is now the premier bank of the non-Chinese world. Here is the SPGlobal ranking of the top 30 global banks as of the spring of 2022.

Source: SPGlobal

JP Morgan is not just the largest non-Chinese bank by size. It is also a universal player with a powerful position in investment banking, retail banking, and asset management.

The crisis has triggered many excellent accounts of how JP Morgan got that way. For something that is somewhat older but goes deeper check out the Economist article from March 2020.

As the Economist report points out, the merger of Bank One and JP Morgan that Jamie Dimon pulled off in 2004 was not doomed to succeed. One of the reasons that JPMC is the only American bank whose return on common equity was higher in 2019 than in 2005 was that in 2005 it trailed so far behind the rest. It is now by some margin the most profitable bank the world has ever seen.

The heritage and the name associated with JPMC goes back centuries. As the FT notes.

Its heritage includes a company started by the US founding father Alexander Hamilton, the investment bank run by legendary financier John Pierpont Morgan as well as lenders that financed the Erie Canal, the Brooklyn Bridge and the UK and French armed forces in the first world war.

But JPMC as a national, universal banking franchise is a new phenomenon.

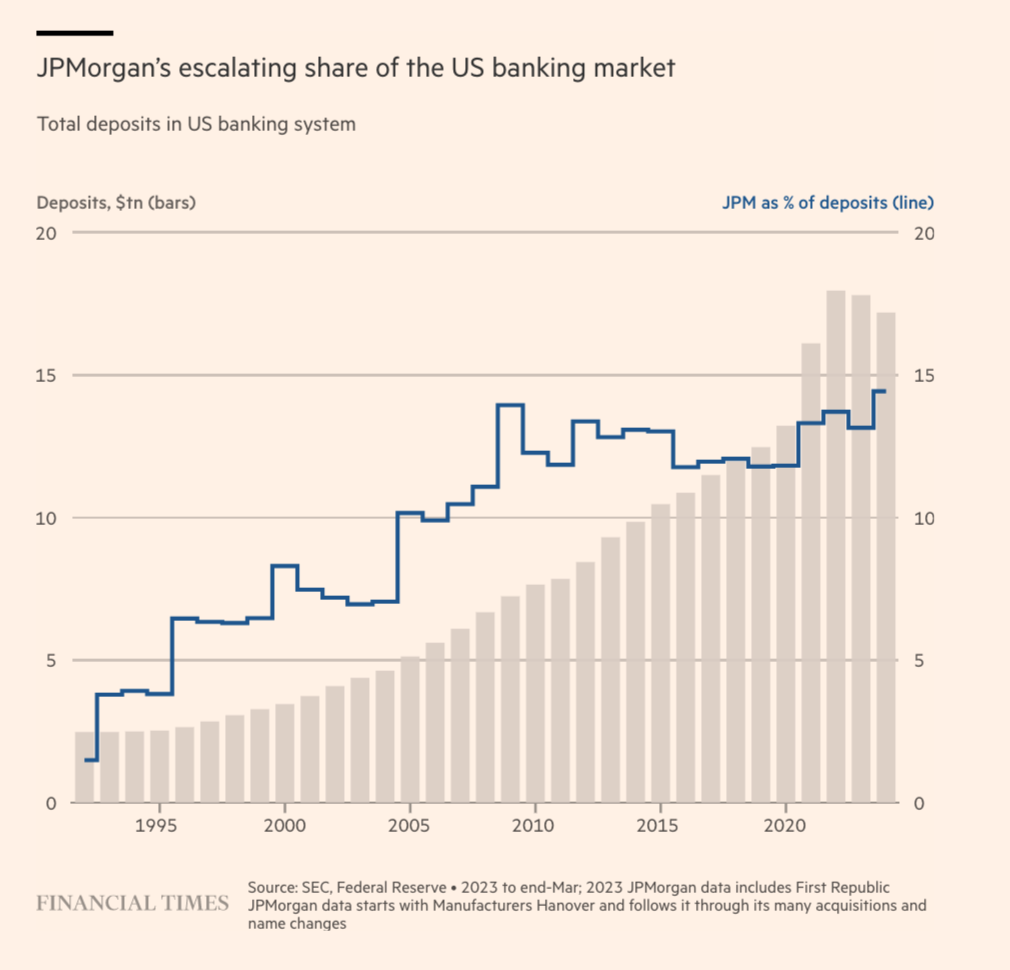

Even as recently as 1991, the retail bank that would eventually become a global banking juggernaut had only $37bn in deposits. The group now has almost $2.5tn and its market share has grown by 10 times, from 1.5 per cent to 14.4 per cent.

Source: FT

This growth was enabled by legislative changes in the 1990s that liberalized interstate banking. Citigroup was the first to take advantage of these, but Jame Dimon made it his personal mission to crush Citigroup in competition and he has succeeded spectacularly.

Whatever one may say about Dimon he is driven and consistent actor. As the Economist notes:

… in his 2005 letter to shareholders, his first as the boss of jpm, he sketched out a vision for the firm that he has stuck with through thick and thin. It registered not only his loathing of bureaucracy and bloat, but also his fondness for a “fortress balance-sheet”. He wrote of the natural connections between different parts of a large bank—between the commercial and investment banks, the credit-card business and the retail bank, and the cash-management and asset-management arms. In summary, Mr Dimon declared that “size, scale and staying power matter”.

***

We are no longer in the era in which Wall Street bankers regularly occupied the job as US Treasury Secretary. But there can be no doubt that as far as strictly financial and banking issues are concerned, JP Morgan and its CEO Jamie Dimon have privileged access to the Fed, the Treasury and the White House.

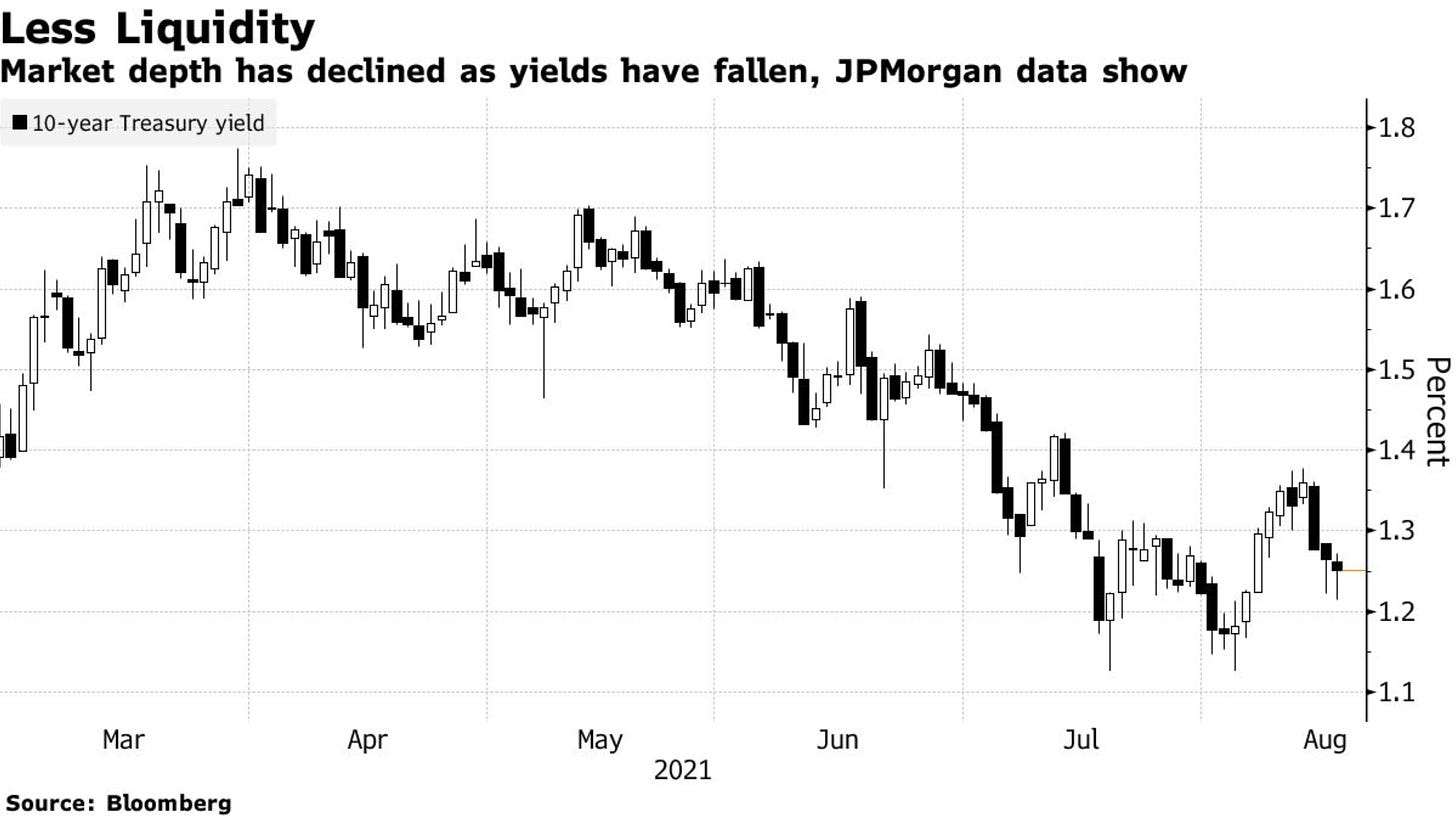

Furthermore, JP Morgan occupies a pivotal position as a broker-dealer and market maker for US Treasuries, the most important financial asset in the world. It is not by accident that even Bloomberg relies on JP Morgan’s data to track that all-important market.

And this is the point at which I want to stand back a bit further to ask about JP Morgan’s significance in a more general sense.

***

Common sense commentary on economic policy is demarcated into distinct domains.

Right now industrial policy, climate, competition with China etc, constitutes one such domain. It is to a surprising degree insulated from macroeconomics. This is one of the many weird effects of the Inflation Reduction Act, which coupled tax incentives to private investment with tax increases. The separation between the industrial policy debate and broader macro is reinforced by the fact that thanks to the subsidies and “animal spirits”, investment is chips and green energy is booming regardless of the Fed’s interest rate hike. So the industrial policy debate exists almost in isolation from the recession debate.

The ongoing banking crisis is tied to industrial policy-tech competition by way of concerns for regional business financing and considerations about the structure of the financial system itself. Should the biggest banks be allowed to dominate? What impact might that have on tech and industrial financing? This is the key concern of folks like Robert Hockett and it is rooted in deep American themes:

For much of its history, the US by law kept its banks local and sector-specific. The Founders had known first-hand the evils of concentrated metropolitan banking — ignorance of local borrowers and economic conditions, focus on short-term profits rather than long-term investments, and related problems. … Regional, community and sector-specific industrial banks like Silicon Valley Bank lent “patient capital” to startups and small businesses — the incubators of future industrial renewal. In other words, the banks were willing to wait years before expecting their startup borrowers to turn profits — essential in industries that require time to scale up before they can become profitable.

They stood ready to fuel the new growth where it was needed, knowing as they did both the special needs of their clients in particular sectors — like tech, for example — and economic conditions in the locales where their clients did business.

Capped deposit insurance is now destroying these banks.

Federal deposit insurance coverage is currently limited to $250,000. That would be plenty for you and me, but the startups and other small businesses on which our industrial recovery depends have large payrolls and weekly operating expenses. For them, $250,000 is mere chump change.

They are thus faced with a Hobson’s choice, especially in times of banking distress like the present: Retain the advantages of regionally focused, client-sensitive, sector-specific Main Street banking at risk of losing deposits in bank runs, or flee to the safety of too-big-to-fail, one-size-fits-all global Wall Street banks that know nothing of their regions’ or businesses’ special conditions or needs.

JP Morgan features in this story as the universal bank predator. It is also, of course, the most enthusiastic funder of fossil capital, as the Union of Concerned Scientists documents here. Between the Paris climate deal and the end of 2021 JP Morgan provided $ 382 billion in fossil funding.

Quite aside from this discussion about banks as institutions of the American Republic, there is the domain of macroeoconomics in which we endlessly ruminate over Fed interest rate policy and (to a much lesser degree right now) the fiscal stance. This is the churning daily conversation in financial markets, especially fixed income markets, which are driven by concerns for inflation, rates and yield curves. JP Morgan’s data serve as key indicators of the state of the Treasury market.

This macroeconomic conversation connects to the banking crisis by way of the impact of the interest rate shock on the balance sheets of badly managed banks like SVB and First Republic, at which moment JP Morgan enters the story as the White Knight.

What slips through the cracks is JP Morgan’s role as a macrofinancial actor of decisive importance and as one of the forces shaping those financial markets.

***

Repo is the key to modern market based financial systems. This is the market in which portfolios of assets are funded by “buying” and “selling” them with a commitment to repurchase at intervals as short as overnight. It was the run on repo, not old fashioned bank runs like the ones that we saw at SVB or First Republic, or on Northern Rock in Britain in 2007, that drove the financial crisis of 2008. In a repo run the counterparties to trades that are normally churned every day in volumes of hundreds of billions of dollars, withdraw their funding. This instantly leaves huge portfolios unfunded, triggering defaults and further withdrawals. The collateral, which is the basis for repo, can be seized but the market ceases to function.

As Carolyn Sissoko showed in an important paper, published in the thick of the COVID financial crisis of 2020, the newly merged JP Morgan Chase in the late 1990s and early 2000s was pivotal to the emergence of the repo-based money market.

As Sissoko puts it in admittedly dramatic terms:

… in 1997, notably the year in which the Asian Financial Crisis took place, JPMorgan moved its repo market making ‘into the bank,’ and then in 2000 became one of the core tri-party clearing banks via a merger with Chase Manhattan Corporation. The end result of this bank intermediation of the repo market was to super-charge it with implicit government guarantees, and to convert JPMorgan Chase (JPMC) into a de facto central bank implementing its own monetary policy through the repo market.

Nominally there were two clearing banks in the triparty-repo market, but de facto Bank of New York Mellon was a fig leaf for JPMC dominant position. This central position was also confirmed by work by Grace Xing Hu, Jun Pan , and Jiang Wang. As they found in their data it was the close connection between JPMC and fund manager like Fidelity that shaped the triparty market.

Though the data are more scanty, there can be no doubt that JPMC is also a key player in the bilateral repo market which is far larger than the better documented triparty market. As Sissoko describes the situation in 2008.

During the height of the boom that preceded the 2007-09 crisis, there is every reason to believe that JPMC had the power to define the repo market both by pricing assets and by setting the terms on repos. Indeed, both Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers failed when JPMC acting as a clearing bank determined that their assets were no longer adequate to support the debt they were carrying. In short, JPMC created a new role in financial markets, the dealer of last resort, a kind of central bank for securities markets that had the capacity, due to the flexibility of too-big-to-fail capital constraints, to price and fund assets over what appeared to be the long-run. Or at least that’s how it appeared until the Bear Stearns failure in 2008.

Sissoko’s story is consistent with the quantitative evidence painstakingly compiled by Gary B. Gorton, Andrew Metrick, and Chase P. Ross in their article “Who ran on repo”. In 2008 at the critical moment in the crisis they show that.

The Flow of Funds data show a significant drop in repo funding to banks and broker-dealers during the financial crisis. The drop was rapid, with net funding to banks and broker-dealers falling from $1.8 trillion in 2007:II to $900 billion in 2009:I. Broker-dealers (AT, most prominently JPMC) also contributed to the run on liabilities by withdrawing funding themselves. Although it is washed out in the net funding numbers, broker-dealers reduced both gross repo assets and gross repo liabilities, with the former dropping by about $490 billion just in 2008:III, the quarter of the Lehman failure.

When JPMC pulled back from Lehman as the first line lender of last resort, it was the Fed that had to step in to backstop the entire banking system of the dollar and eurodollar world.

The key point here is that the growth of JPMC is not simply a corporate success story. And JP Morgan’s power is not limited to its ability to profit from its strong balance sheet or its excellent connections in Treasury, Fed and White House, to snap up rivals. The financial markets, as we know them in the US today, are to a significant extent moulded around JPMC’s business model and its decisions have macroscopic effects. This is the flipside of Jamie Dimon’s posturing as a patriotic servant of financial stability.

***

Perhaps the most dramatic demonstration of this connection came in 2019 with the so-called repo market shock that preceded the COVID crisis. As Nick Dunbar at Risky Finance showed with some excellent number-grubbing, JPMC was at the heart of this story.

As a reminder

On 17 September (2019), the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR), which had hitherto closely tracked the Federal Funds rate, suddenly rocketed up to 10%. For a brief moment, US dollar repo enjoyed the same overnight funding cost as Brazil.

At this moment, banks were not doing their customary job of lending out the cash that the Federal Reserve had provided (via reserve balances). They had stopped purchasing treasury bonds and other securities from counterparties, which they would resell a short time later at a slightly lower price. The Fed had to step in and start lending instead, providing up to $75 billion each day.

To understand what happened it emerged that one had to understand what was happening at JPMC

Between June 2018 and June 2019, JP Morgan’s cash and reserve balance fell by $138 billion, a decline of more than a third. By contrast, cash and reserve balances for the other five largest US banks barely fell at all during this period, as the Risky finance banking tool shows. … As the Bank for International Settlements noted in its December 2019 quarterly report, the reduction in cash by “top four banks” (read JP Morgan) coincided with a structural change in the repo market – instead of using repo as a funding source as they had done in the past, the

largest US banksJP Morgan instead became a net provider of funding. We see this in the chart of net repo assets versus liabilities of the banks over time. While the BIS took care to anonymise the names of the largest banks in its study, we can be less circumspect. According to Risky Finance data, JP Morgan accounted for 41% of all repo lending by the six biggest US banks at the end of 2016. By June 2019, this had increased to 46%, or $465 billion of repo loans. In effect, JP Morgan was the lender-of-last-resort to the repo market.

Dunbar’s use of the strikethrough – largest US banksJP Morgan – is a brilliant device to highlight the way in which reporting conventions encode, obscure and thus also help to perpetuate structures of power in the operation of our financial system. It makes a big difference politically whether you gesture vaguely and complacently to “markets” or actually name names.

***

Unlike in 2008 or 2019 there is no reason to think that JPMC is a significant driver of the troubles that have befallen the smaller regional banks in the US in recent months. The point to be made here is not to name and shame. But to suggest something more general:

When we tell the story of JP Morgan under Jamie Dimon as a case study in business success we are conforming to conventional ways of thinking about economic reality, which separates macro and micro, economic from business news, managerial success from economic policy deliberation. But in so doing we are understating JPMC significance to the operation of the dollar-based financial system and thus to the political economy not just of the United States but of the world today.

Max Abelson and Hannah Levitt wrap their piece for Bloomberg with a nice set of observations

If you’re tempted to compare it to BlackRock, remember that the money manager’s $9 trillion of assets are in funds it oversees for clients. JPMorgan, by comparison, finances the world (and has an asset management operation that’s itself about a third the size of BlackRock). And it processes more than $5 trillion of payments a day. You can think of it as an empire all its own. Bloomberg Opinion columnist John Authers goes further, calling Jamie Dimon the sun around which the financial system revolves and describing JPMorgan as a kind of public utility, big enough for the government itself to depend on. Dimon likes to say that the bank has a fortress balance sheet, an image that political economist Mark Blyth elaborates on. “If the only game in town is a medieval fortress, I want to be inside,” says Blyth, who runs the William R. Rhodes Center for International Economics and Finance at Brown University. “Hey, we have the castle. Don’t you want to be in the castle? It’s dangerous out there.” In the first three months of the year, as other banks saw savers depart, deposits at JPMorgan rose. But there’s a problem with everyone wanting to be in the castle. “What happens if the castle walls get breached?” Blyth asks. “We’re all screwed.” Economic power in the US runs in eras. As Blyth puts it, after World War II, when society more or less had to be rebuilt, the fiscal capacity of the US Treasury dominated. When inflation became the enemy and the Fed had the power to fight it, fiscal dominance gave way to monetary dominance. Now too-big-to-fail banks’ becoming bigger could usher in something new. “We may be in a world of financial dominance,” he says. “I don’t know, but it sure smells that way.”

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you wil receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.