How does the current rash of banking crises compare to 2008? The GFC was a slow-burning affair. Does what we have seen so far in 2023 resemble the overture in 2007? Could we be in for a major shock to come? It is too early to tell and there may be more to come, but, so far, the differences between 2023 and 2008 are more striking than the similarities.

***

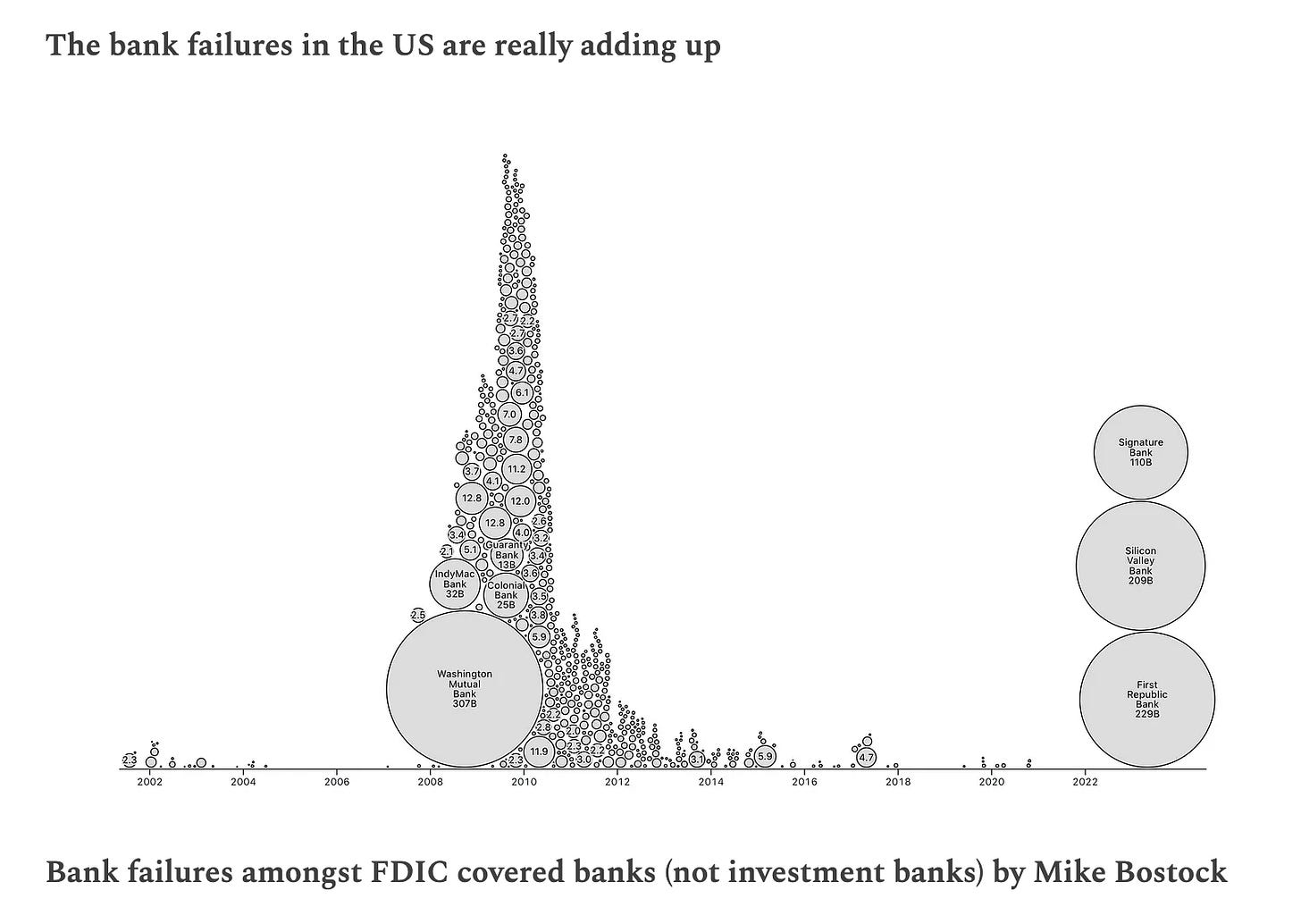

As this fantastic graphic makes clear, there is nothing small about the trio of banking crises that have rocked the US since the beginning of 2023. These are major events.

Admittedly, the graph is based on a wonderfully clever presentation of FDIC data. This means that it does not cover the biggest failure of 2008. The collapse of Lehman Brothers, an investment bank not covered by the FDIC, was roughly the size of all three of the 2023 failures put together – $639 billion in assets. The graph would look quite different if that giant bubble was added in 2008.

But it is not simply the question of balance sheet size that differentiates 2023 from what transpired in 2007-2009.

***

The most basic difference between then and now is the economic backdrop.

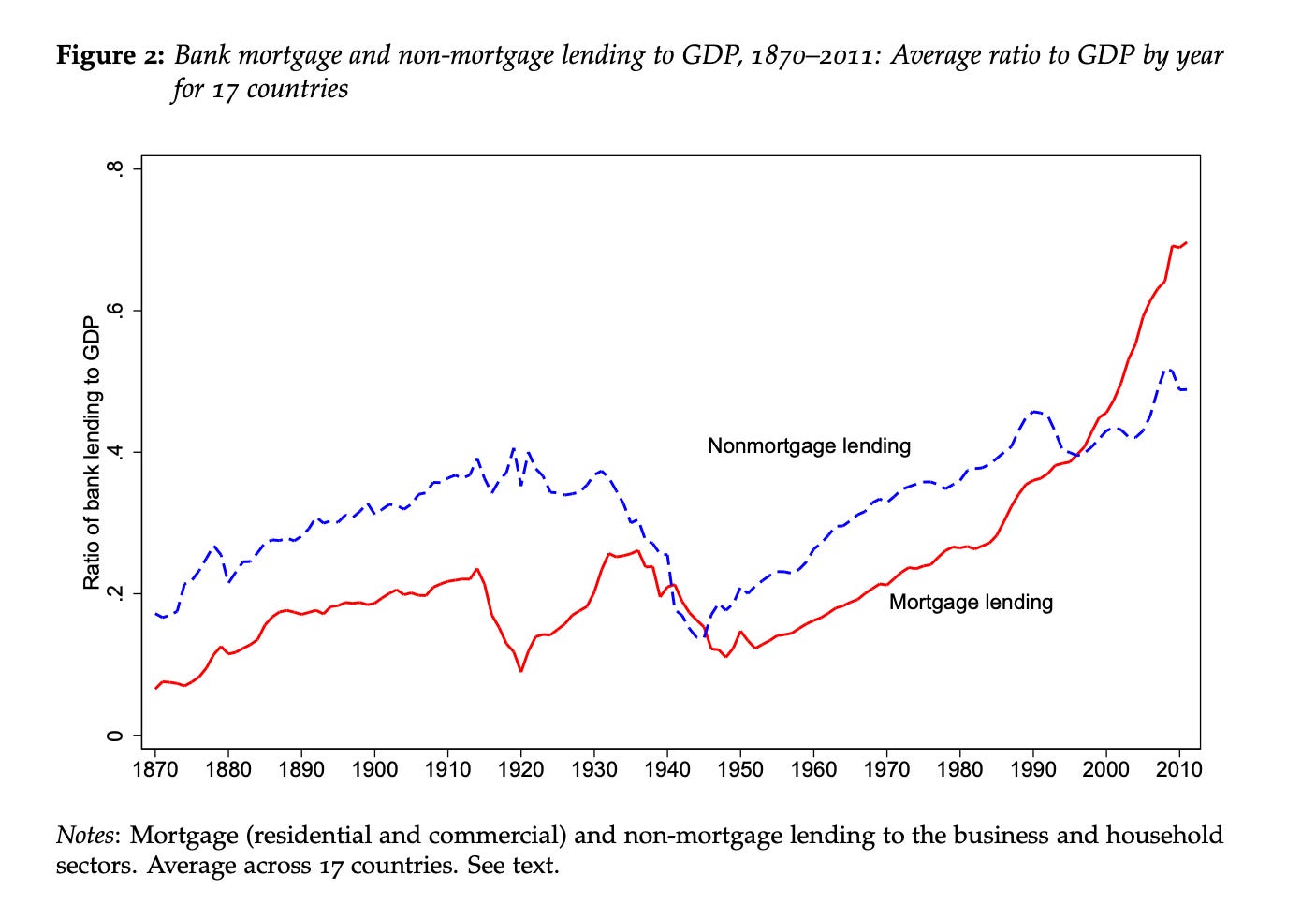

The crisis in 2007 was triggered by the unraveling, on both sides of the Atlantic, of a giant, credit-fueled real estate bubble – the culminating point of what Jorda, Schularick and Taylor have called the “great mortgaging”.

Given the historic scale of this housing market bust, even if there had not been bank failures, after 2007 the economies of Spain, Ireland, California and Florida – the economies most heavily dependent on real estate – were in for a deep recession. It was the turning point in house prices that triggered a credit event, spreading losses and panic through the financial system.

Our situation is very different. The immediate source of the shock today is not the business-cycle as such, but the Fed’s interest rate hike, which itself is driven by the need to respond to a historically unique surge in post-COVID inflation. It is the sudden hike in interest rates that has rocked the balance sheets of banks that overcommitted to long-term investments in low-rate assets, whether those be US Treasuries or the jumbo mortgages issued to First Republic’s affluent clients.

Far from facing a significant recession, the Fed’s rates have had to go as high as they have because the real economy is “too” robust. Unemployment in the United States has fallen to record lows. Europe is as close to full employment as it has been in years.

This is not to say that the hike in rates will not in future deliver a nasty shock to the housing market. It surely will. We have already seen some failures of small US mortgage lenders. There is much to worry about in the commercial real estate sector. But, if that is, indeed, the shock to come, it is not what we have seen so far.

SVB had a lot of government-guaranteed mortgage-backed bonds on its balance sheet, but the problem with those was not that they were in default, but that the rates they offered were too low and the bank was facing large mark-to-market losses.

***

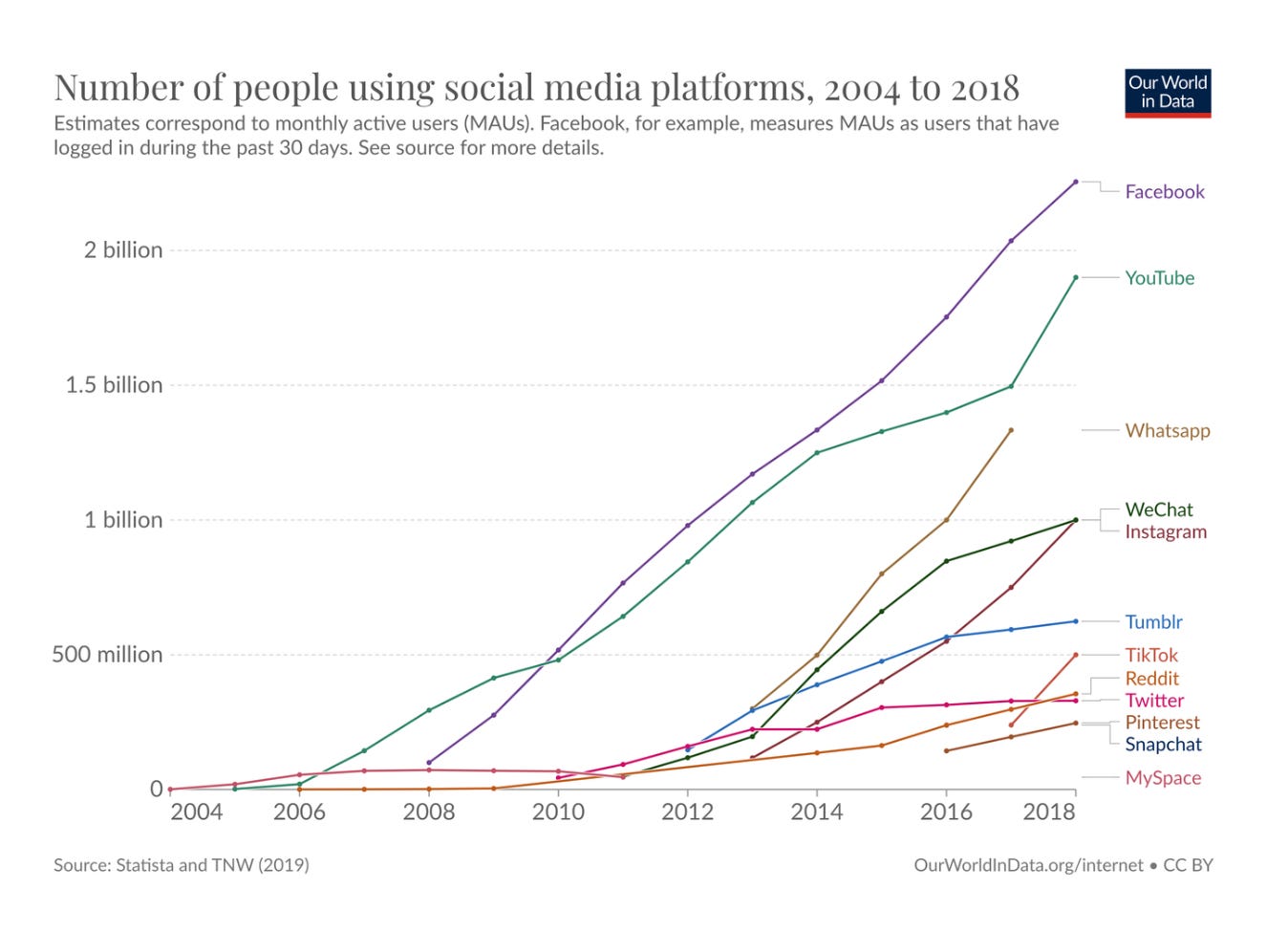

There has been a lot of talk in the current context about the speed of the bank runs on SVB and First Republic. This is commonly attributed to the rise of social media and digital banking. In 2008 both were still in their infancy. Smartphones and platforms like Facebook took off just as Lehman failed.

Source: Our World in Data

Digital communication no doubt speeds up the spread of news. Bank runs are news-driven events. This may have played some role in accelerating how quickly deposits drained out of SVB and First Republic.

But as shocking as they may have been, the fact that the current rash of banking crises have been classic bank runs is good news. Because it was not conventional bank runs that made 2008 so dangerous.

There were classic bank runs in 2007-8, at Northern Rock and Washington Mutual. But the crisis that brought Lehman to its knees in September 2008 was not a run of small depositors or business accounts. Lehman had no mom and pop accounts. What brought Northern Rock, Bear Stearns and then Lehman down was a collapse in their short-term ultra footloose market-based funding. Specifically what killed Lehman was what Gorton and Metrick called a “run on repo”.

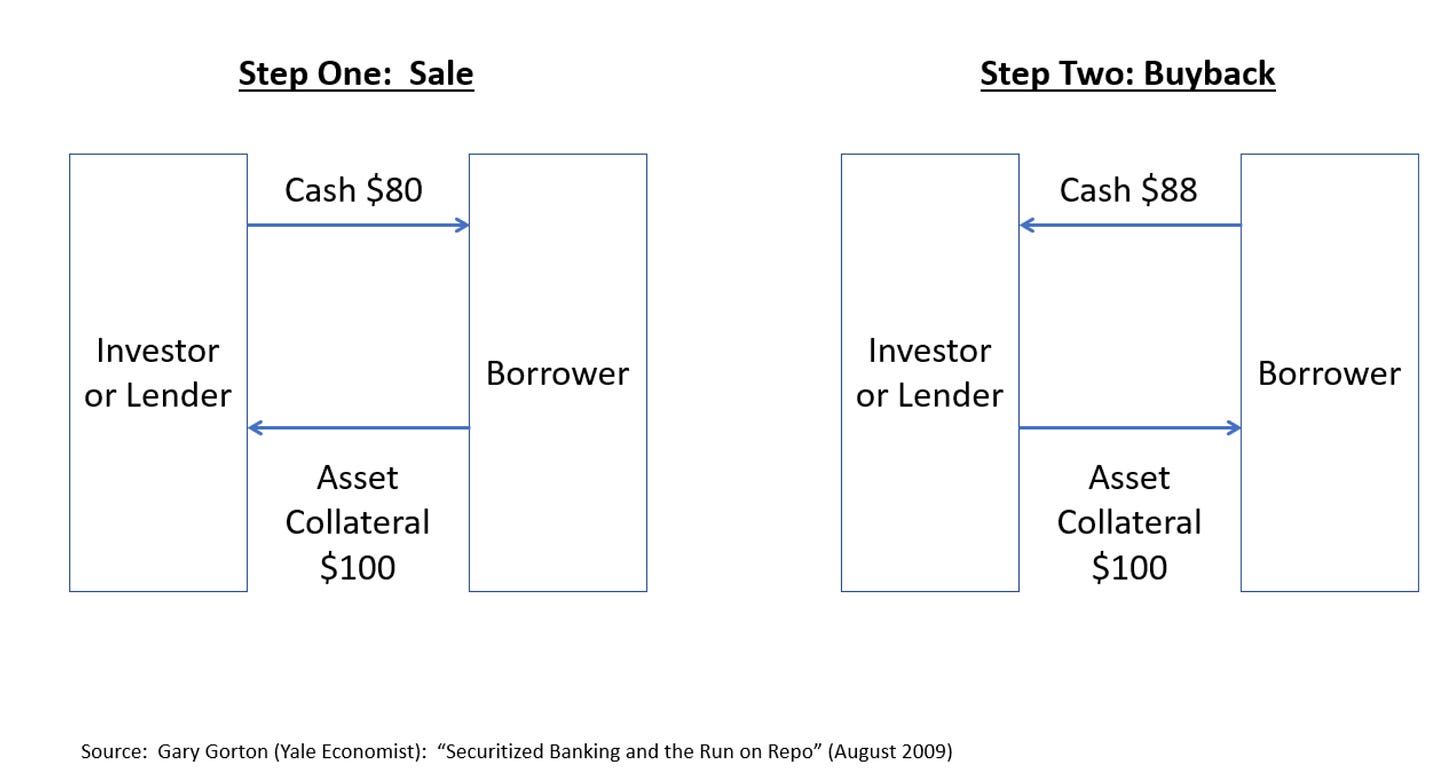

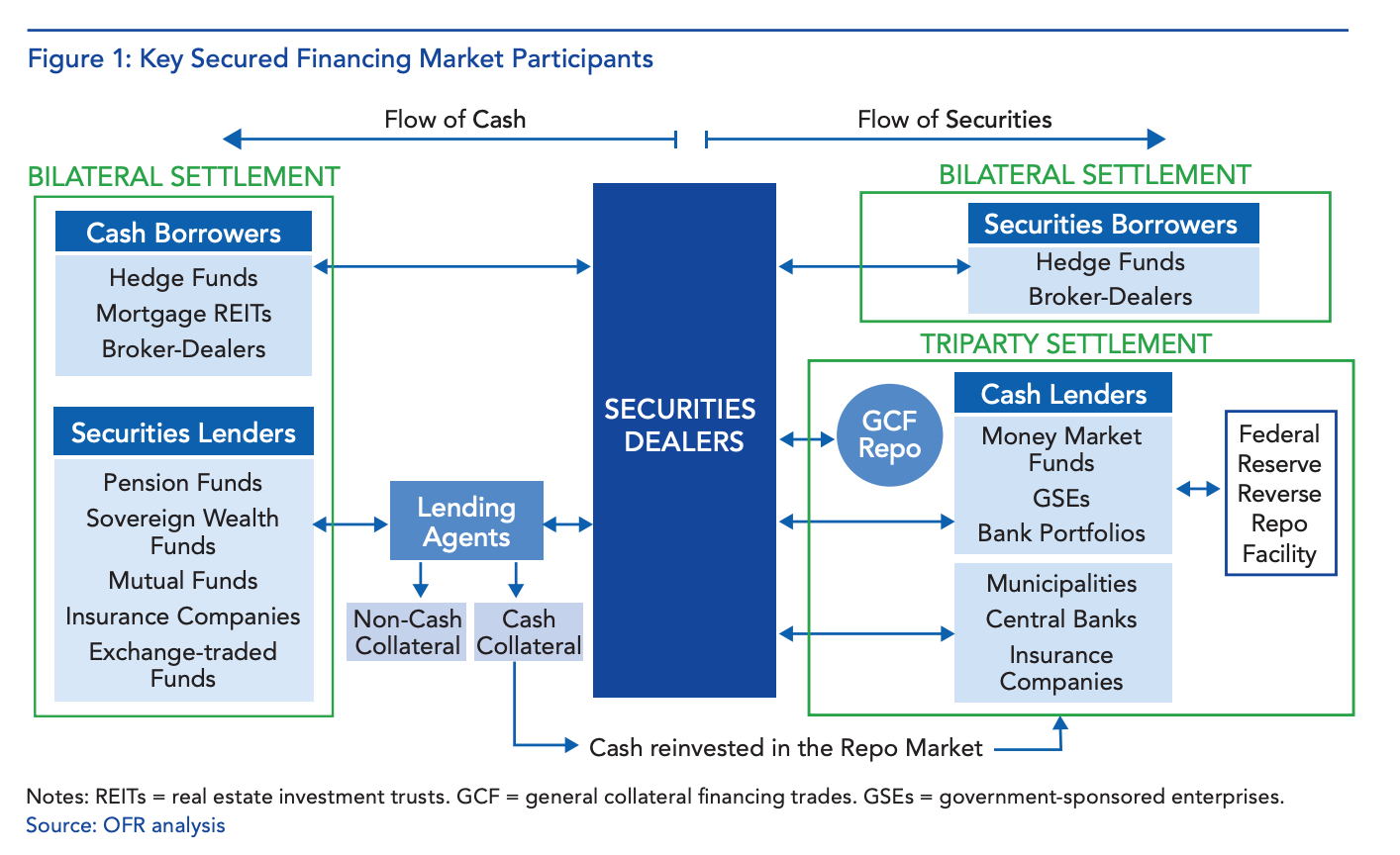

Repo is the market, operating between major players in the financial system, through which banks like Lehman financed portfolio of mortgage backed securities and other fixed-income assets. In repo-based banking, funding is obtained not by taking deposits and then investing the funds in interest and profit-yielding assets. Funding is obtained by buying an asset, like a Treasury or a mortgage-backed security and immediately selling it, with the promise to repurchase at some point in the not too distant future, only then to repeat the operation, again and again until the bond matures, or it is disposed of. In the overnight repo market this churn takes place literally every day.

One might imagine the repo markets and its participants as a staggeringly over-sized pawn shop ecosystem. Every day collateral is given, credit is issued and then the original owner redeems the collateral the following day. And this takes place daily on the scale of trillions of dollars.

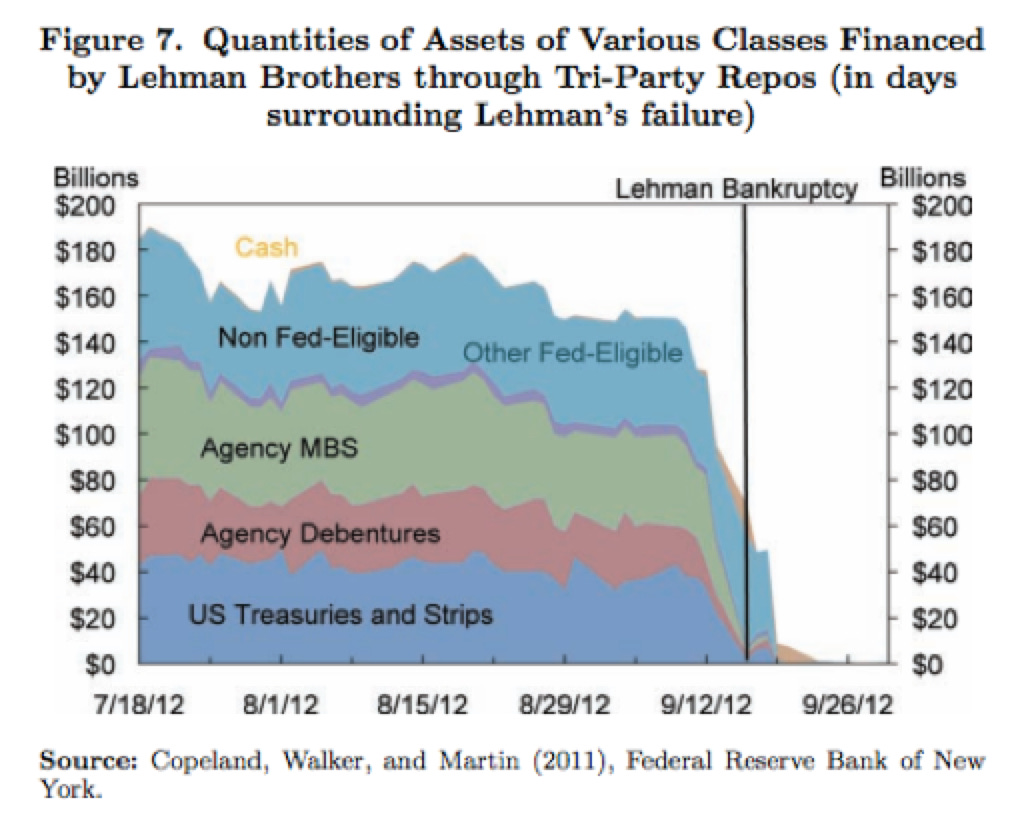

Clearly, this is spectacularly more elastic, dynamic and labile system than deposit-based banking. A run in this market consists simply in trading parties, who normally show up to sell, buy and repurchase collateral – mainly Treasuries or other fixed-income assets – one day refusing to transact with a particular counterparty. For Lehman this was a $160 billion shock delivered in a matter of days.

To state the obvious, this hidden “run” on Lehman dwarfs anything we have seen in 2023 in terms of scale and speed. The news of Lehman’s situation was no doubt communicated around Wall Street on Blackberries and Nokias, by emails and phone calls. But the medium and the ease of communication was not the point. It was the scale of the market and its structure – a highly volatile system for financing assets of durations measured in years or even decades on ultra-short-term funding – that created the risk.

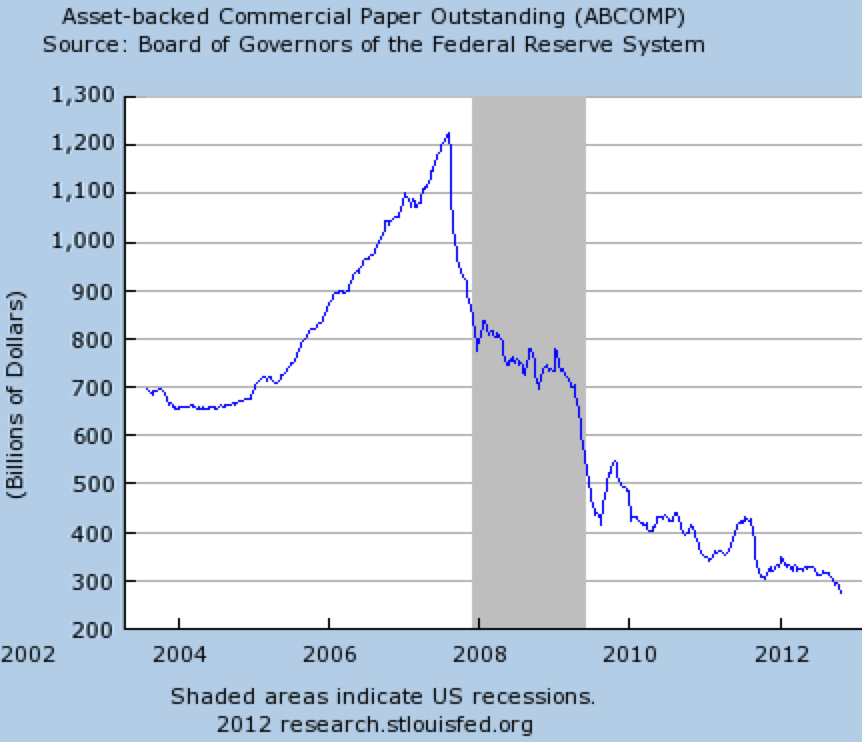

The tension in the market-based funding system for the megabanks of the period began to build up already in 2007. The asset backed commercial paper market began to shut down in August 2007

If anything of the kind were to be visible in the current moment, it would be a loud alarm bell ringing. But, so far, rather than a flight from the system of market-funding we have seen depositors withdraw cash from their bank accounts, which in the United States pay virtually no interest, so as to transfer them to money market mutual funds, which are an integral part of the repo market ecosystem.

Source: OFR

Not until we see shockwaves rocking the system of market-based funding, as we did in 2007-8 and again in 2020, will 2023 really begin to register on the Richter scale of financial shocks.

***

Furthermore, you cannot judge a crisis, or any other historical event for that matter, only by what actually happens. To take the measure of a historical moment you have to understand what lurks, as yet unrealized on the horizon – what Reinhart Koselleck called the horizon of expectation.

What made 2007-8 so terrifying was not simply the carnage in the mortgage lending sector, or Lehman’s failure. The terror for those in the financial system, were the dangers that lurked on the balance sheets of the world’s monstrously over-sized universal banks.

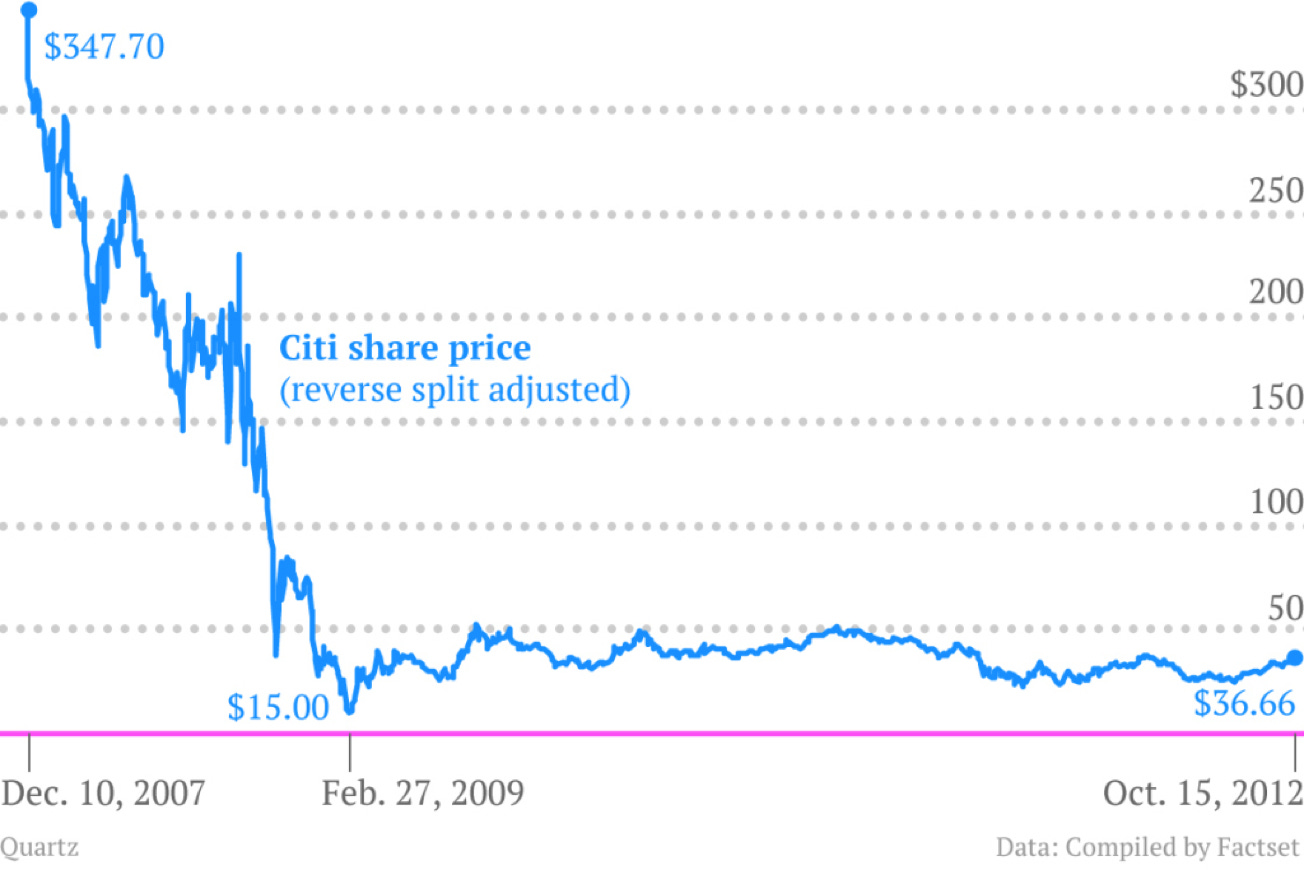

Citigroup and Bank of America, the two most vulnerable of the giant banks in the US, were not out of danger until the second half of 2009. Unlike Lehman, they were never allowed to get to the edge of failure because it was not clear that if they had reached that point they could have been contained. Their balance sheets were simply too large and complex. But the market gave its judgement on their true health. Their shares were written down to a fraction of their pre-crisis level.

Beyond the American giants there were also a huddle of huge banks in Europe that were also in deep trouble and had large footprints in Wall Street and in US mortgage funding. It is not for nothing that the Fed disbursed a majority of its direct liquidity support to non-American banks and set up the swap lines to provide even more dollars to the world’s central banks. It is not for nothing that 2008 gave rise to a special regime of regulation for the banks designated as G-SIB.

So far in 2023 those kinds of shadows do not hang over us. Already in 2020, faced with the gigantic COVID shock, the balance sheets of the biggest banks proved relatively robust.

What about Credit Suisse you ask?

Well, the good news about Credit Suisse is precisely that what brought it down was not a 2008-style market-based funding crisis but something akin to a classic bank run. Unusually for a bank of its size, it sustained massive withdrawals by depositors over the best part of six months that made its positions unsustainable.

***

There are aspects of financial history that attract simplistic social psychological generalization. Banks are creatures of confidence. Confidence is fickle, subject to the forces of crowd psychology etc etc. All too easily this produces a rather flat account of financial panics and manias, from the tulip bubble to Lehman. The same mechanisms repeat themselves.

It would be foolish to deny that some generic features of financial economics have real force. A bank with a balance sheet like that of SVB is going to be vulnerable to runs, whatever the historical situation. In this post I’ve referred to a “classic bank run”, i.e. a confidence-driven depositor stampede.

But the existence of SVB, or First Republic or Lehman, in the form that they took before they failed, can be explained only by rather peculiar historical features. The shocks that brought them down were historically unique too. There had never been. a mortgage boom quite like that before 2008. The interest rate shock of 2022-2023 is the most severe since the 1980s and follows a period of uniquely low rates. And how they fail depends critically on the logic of their business model. With hindsight, the funding structures that collapsed in 2008 were the equivalent of driving without seatbelts or smoking indoors, a reflection of time bound and institutionally defined behavioral norms that seem barely comprehensible today.

It cannot be ruled out, of course, that in two or three years time we will look back on this moment and be able to recognize financial structures that with hindsight appear astonishing in their obvious danger. SVB boggles the mind.

There may be more to come, perhaps in the realm of private finance. In any case, it is on the constantly evolving structures of finance and on the suspiciously opaque links in the chain that we should be focusing our attention, rather than relapsing into an account of history viewed as the arena of trans-historic psychological patterns.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you wil receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.