For the last twenty years the German economy has thrived on globalization. Now that formula seems under pressure from many sides. Close trading and investment relations with China are yet another facet of the “German model” – after Russian gas – that is being called into question by our current polycrisis.

Berlin still cleaves to the EU mantra that China may be a systemic rival, but it is also conventional economic competitor and on key issues like climate and global pandemics, an indispensable partner. In recent days Chancellor Olaf Scholz has travelled to Beijing with the explicit message that whatever the current climate, Germany is not interested in decoupling from China. Berlin’s aim is to avoid dangerous dependencies and to ensure reciprocity. But Scholz intends to proceed with a sense of “proportion and pragmatism”, which is hardly the prevailing mood in Washington DC right now. All the signs are that Berlin still wants to walk the tightrope.

But what if that is no longer an option? In the lengthy article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, in which Scholz laid out the motivations for his controversial solo visit to Beijing, he attributed the trend towards decoupling to China, to Beijing’s “dual circuit” model and its drive to achieve technological autonomy. He made no mention of America’s strategic objectives or its determined drive to halt China’s high-tech development in its tracks. Of the two it is no secret that it is America’s uncoupling drive that is far more uncomfortable for German business than that by China, which still rolls out the red carpet for German investment.

Scholz also made no mention of the fundamental difference between Germany and the vast majority of its Western partners in their dealings with China. For the United States, decoupling from China raises issues of supply-chains, but it goes hand in hand with the basic protectionist impulse to redress a large trade deficit. For Germany the opposite is the case. China is a vital market for many German industrial exporters. For much of the last decade Germany ran a trade surplus with China. So much so that the question arises whether in the process of decoupling from China, Germany is at risk of losing a major driver of its economic growth.

How vulnerable is the German economy to decoupling and geopolitical confrontation between China and the West?

On this score caution is warranted. In the current moment, criticism of the “German model” have about it the air of Schadenfreude. To critics it is pleasing to note the way in which the German model is unravelling and to highlight the way in which Germany’s year of success were owed to dirty compromises with regimes like those of Russia and China. But such criticism is often simplistic and argumentatively tendentious.

With regard to Russian gas, I’ve argued in Chartbook #150 that there is an element of exaggeration and discursive overshoot in play. It is certainly true that the loss of Russian gas is a major blow to Germany. That is hardly surprising, any abrupt change in well-established trading relationships for a key energy source is bound to be disruptive. But it is quite another thing to claim that because Germany bought a lot of gas from Russia this materially contributed to the success of German exports, such that it is reasonable to say that the German model was dependent on “cheap Russian gas”. The evidence for that far-reaching causal claim is surprisingly weak.

So how about China? What is the significance of China for the German economy.

Recently, Brad Setser – who is an essential follow at @Brad_Setser – offered a nice macroeconomic debunking of the claim that China is currently an important driver of German economic growth.

It is true that since the 1990s Germany’s position has been unusual in that its sophisticated industrial manufacturing base was complementary to China’s economic development. Germany, though it suffered a “China shock” through cheap imports, also gained an offsetting boost through the success of its exports to China. As a result, Germany is the rare Western economy that since 2009 has run a trade surplus with China.

China now reports a small surplus in its trade with Germany. That is a big change.

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) October 29, 2022

Bilateral trade data can mislead — but the Chinese data vis a vis Germany easily nests inside the broader data for both Germany and China.

5/ pic.twitter.com/zocrlrcbrv

This was conditioned both by industrial complementarity and the fact that German fiscal policy and wage policy were biased against imports and towards export-led growth. In this regard you could say that Germany beat China at its own game. Whereas China used exchange controls to prevent the revaluation of its currency, Germany merged the Deutschmark with the euro. In recent years, however, Chinese exports to Germany have surged, meaning that the trade balance with China is now in slight deficit. Meanwhile, if we examine German exports to China, as Setser shows, German exports have been flat since 2012.

German exports to China really did provide a positive impulse to Germany's economy in the years immediately after the global crisis.

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) October 29, 2022

But German exports (measured by Chinese imports) have been basically flat since mid 2012. The growth impulse was all from 05 through 11. pic.twitter.com/x5z3VbAWQ2

The implication is that German exports to China did provide a substantial boost to demand for German industrial goods from the late 1990s through 2012. But since then, exports to China as a share of German GDP have plateaued at a level between 2.5 and 2.75 percent of German GDP. This is substantial, but as a static share of GDP, exports to China can no longer be plausibly seen as a current “driver” of growth.

Of course, if German trade with China were suddenly to be interrupted, that would deliver a severe and dislocating shock to the German economy, to the tune of 2.5 percent of GDP, plus multiplier effects. It is unlikely that other markets could absorb the goods that Germany would otherwise sell to China. So, German industry would be idled or have to dump goods at distressed prices. Nor is it likely that Germany could find domestic sources for the goods it currently imports from China. So it would either suffer supply chain bottlenecks or switch demand to other overseas suppliers.

Were this shock uncoupling to happen, critics would no doubt claim that it demonstrated the “dependence” of the German economy on China-trade. As with the Russian gas that would be an exaggeration. But as in the Russian case, it would be very bad news.

As with Russian gas, you get the most stark view of the depth of Sino-German interconnection if you shift the point of view from the macroeconomic balances to the balance sheets of individual corporations.

Handelsblatt recently compiled these data for the most heavily China-dependent corporations in Germany’s Dax stock exchange index.

Source: Handelsblatt

Given China’s weight in global GDP and its significance as a driver of global growth these large numbers are not by themselves surprising. But for Germany’s lone semiconductor champion – Infineon (formerly Siemens) – and for Germany’s entire automotive industry, China is clearly very important indeed. And this matters because whereas in GDP terms, one euro is the same as another, in terms of political economy the fortunes of the major corporate players have a disproportionate significance. When Scholz travels to China he does not take slices of German GDP as part of his delegation, he takes the CEOs of Siemens, VW and BASF – large and powerful, highly sophisticated corporate organizations enmeshed in national and international networks of power. Their weight in the political economy vastly exceeds their share of total value added.

For the powerful group of German firms, whose businesses are deeply engaged in China, three questions that matter: Is their business following the same pattern that Brad Setser has highlighted in the aggregate trade data. Has their business in China plateaued? Apart from sales, how are their profits? And what is the outlook for the China business? What strategic plans are major German corporations making? It is not easy to get a complete picture on all three of these questions but from recent reporting a clear picture does emerge, not of corporate German withdrawing from China, but of new engagement.

Amongst the Dax group highlighted by Handelsblatt a number have recently made strategic announcements on China.

Though for BASF Germany remains the most important market for revenues, accounting for 18 per cent of its sales in the year to date, compared with 14 per cent from China, the company has recently announced that it was intending to

“downsize “permanently” in Europe, with high energy costs making the region increasingly uncompetitive. The statement from the world’s largest chemicals group by revenue came after it opened the first part of its new €10bn plastics engineering facility in China a month ago, which it said would support growing demand in the country. “The European chemical market has been growing only weakly for about a decade [and] the significant increase in natural gas and power prices over the course of this year is putting pressure on chemical value chains,” chief executive Martin Brudermüller said on Wednesday.

As the FT reports:

BASF’s chief executive Martin Brudermüller has defended the approach and hit out at critics of his China investments. “I think it’s urgently necessary to stop this China bashing and look at ourselves a bit more self-critically,” he said last week. Experts say BASF has little choice but to focus its efforts on China. “China has 60 per cent of the world’s chemical companies and talent and 40 per cent of the resources,” says Wang Yiwei, professor of international relations at Renmin University and an adviser to the Chinese government. “If they don’t invest in China, where do they go?”

Covestro is less high-profile than BASF, but the spin-off from Bayer is also thoroughly committed to the China market. It recently announced a substantial expansion of its Shanghai production site for polyurethane dispersions and elastomers.

At Siemens, CEO Roland Busch like his predecessor Joe Kaeser is an unapologetic China bull. Under the code name Marco Polo he is driving a major program to prioritize development of Siemens digital industries in China.

For VW, China is quite simple existential. But it is a market in which the company is struggling to maintain its position. For many years VW was the leading car brand in China and the China business made a major contribution to its bottom line. But sales peaked in 2019 at 4.23 million units and have fallen sharply since.

Source: VW

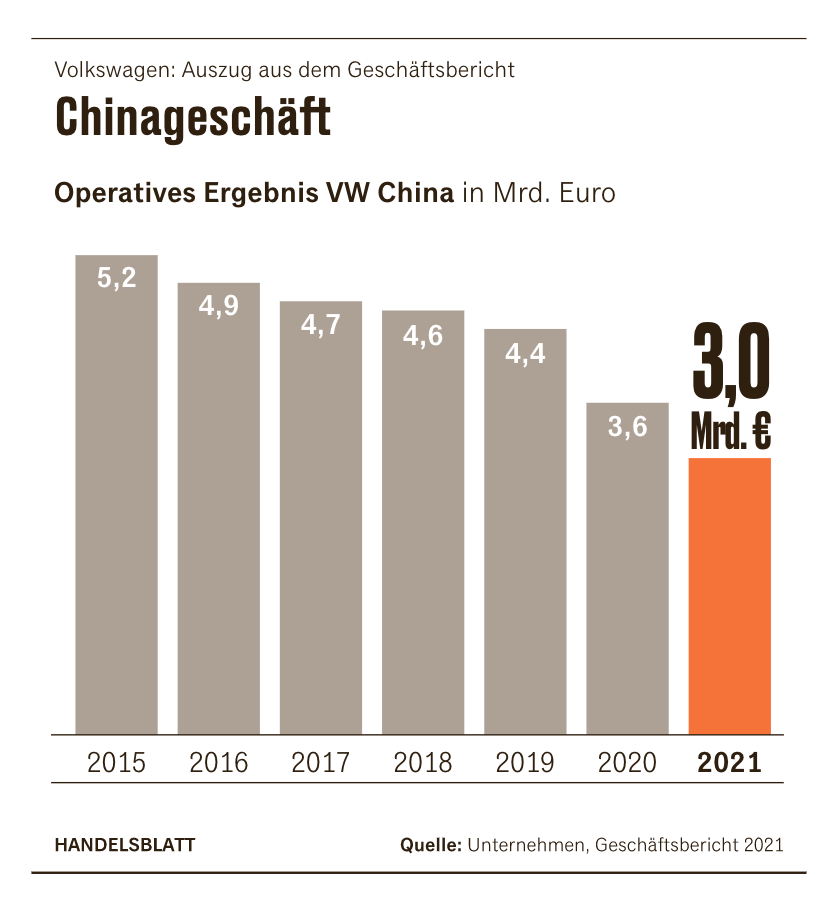

VW’s China profits which once ran to over 5 bn Euros per annum have slumped to no more than 3 billion.

Source: Handelsbatt

But the firm has no plans to exit China or rethink its commitment, on the contrary. To increase its ability to respond to challenges in the China market, VW has opted to reorganize and localize control. As Electric Drive reports:

“The China region is being given significantly greater decision-making powers and autonomy,” says Brandstätter, who himself will take over the management of Volkswagen Group China and responsibility for the Chinese market on the Group Board of Management on 1 August. “We are therefore tailoring our services, technologies and products even faster and more consistently to the specific needs of our local customers.”

On October 13 VW’s China management team announced a “€2.4bn in a joint venture with one of China’s leading designers of artificial intelligence chips, as the carmaker bets on AI-assisted and driverless cars as a way to retain share in its biggest market.” This followed an announcement a week earlier of a 1 bn euro investment in a software development joint venture.

VW’s competitors in the German auto industry are no less clear about their commitment to involvement in China.

Ola Kallenius, CEO of Mercedes Benz, meanwhile, has suggested the west’s hands will be tied if Beijing were to try to seize Taiwan. “If one thinks that the Chinese economy could be unbundled from the European or the American, it is a total illusion,” he said in an interview with Die Welt in September. “It would have dramatic consequences for the world economy that would in no way be comparable to those of the Ukraine war.” BMW CEO Oliver Zipse October 19 even went so far as to defend China’s market policies and compare them favorably to how President Joe Biden is changing the playing field in the U.S. The 50-50 joint ventures that Beijing required foreign carmakers to set up in China were “fair for everyone,” Zipse said in an interview near BMW’s plant in Spartanburg, South Carolina. He warned that the Biden administration’s climate law designed to wean the US off battery materials sourced from China could provoke retaliatory steps and set off a “dangerous” game of trade barriers.

The ongoing commitment by corporate Germany to China shows up at the aggregate level in figures for direct investment. All in all, a recent IW economic research report concludes that German direct investment in China in the first half of 2022 has hit a record 10 billion euros. This is more than the annual total in any previous year and twice the level in 2021. The report’s title reads – “full steam ahead in the wrong direction”.

The title is telling. Though the assessment of China in German business has not turned to the degree that it has in the United States. It is nevertheless striking that the solid front of political and expert backing behind the German model is crumbling from within. It is not just economists like those who wrote the IW report who warn of traveling in the wrong direction. The Ministry of Economics and Climate under the command of Green Party boss Robert Habeck has taken an increasingly skeptical view, word of which is leaking to newspapers like the FT:

In May, Habeck’s economy ministry refused to extend Volkswagen’s investment guarantees for China, citing the repression of Muslim Uyghurs in the western region of Xinjiang. The ministry is now working on plans to cap the number of such guarantees for China. “They . . . are massively skewed to China right now,” says one official. On the other hand, many in Berlin are sceptical that such moves have much impact. The evidence suggests that companies will continue to invest in China, if necessary without the guarantees. Officials acknowledge they wield little influence over corporate decision makers. “If Brudermüller thinks investing €10bn in China is the right thing to do, it’s ultimately a question for BASF’s shareholders,” says the official. “But I do think we have to send a signal to companies that if their shareholders endorse it — fine, but please don’t count on the German government to underwrite it.”

Clearly the German elite are trying to find a way to navigate a new world beyond the self-evidence of globalization. Geopolitical tensions are mounting on all sides. But the collective imperative to face the technological challenge of the energy transition remains and China remains a key arena for global economic development. It is tempting to see this as a crisis peculiar to the German model. But in fact it is an expression of forces that are making themselves felt around the world in the current moment of polycrisis – the intersection of multiple, diverse, incommensurate and yet interacting forces that are disrupting the once taken for granted logic of economic globalization and the American-led unipolar order.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. I love sending out the newsletter for free to readers around the world. I’m glad you follow it. It is rewarding to write, but it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button.

Several times per week, paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

There are three subscription models:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

To get the full Top Links and become a supporter of Chartbook, click here: