On 14 October 2022, the World Food Program issued an appeal that is unprecedented for the Western hemisphere. It concerns Haiti.

According to the latest IPC analysis, the WFP found that a record 4.7 million people in Haiti are currently facing acute hunger (IPC 3 and above), including 1.8 million people in Emergency phase (IPC 4) and, for the first time ever in Haiti, 19,000 people in the capital city of Port-au-Prince are in Catastrophe phase (IPC 5). This means that they are at imminent risk of outright starvation.

Outside Haiti’s urban areas, food security has continued to deteriorate. Below average rainfall and the 2021 earthquake caused widespread devastation and loss of harvest in cultivated areas of the Grand´Anse, Nippes and Sud departments.

The WPF is scrambling to distribute food and basic assistance:

In 2021, WFP reached 1.3 million people and in 2022 plans to reach 1.7 million Haitians. Over the next six months, WFP requires US$ 105 million for crisis response and to tackle root causes and bolster the resilience of Haitian.

Cholera, a classic disease of malnutrition, is spreading rapidly through Haiti’s slums.

The message from the UN is alarming and needs to be heard amongst the general din of bad news: This is not the normality of Haiti’s “ordinary” poverty or crisis. The current situation is far more dangerous and urgent. It is also unprecedented. Large numbers of people in the Western hemisphere are on the point of outright starvation.

***

This acute crisis is the result of a long story of state collapse, failed intervention, violence, exploitation going all the way back to Haiti’s historic uprising against slavery. But that trajectory has always been cross cut by global pressures. Indeed, this defines the history of the entire Caribbean, since first contact with the Europeans. Arguably the Caribbean is, as a result, the first modern place, where entire social systems and habitats were transformed by violent developmental change and global conquest.

In 2022 Haiti is perhaps the most urgent example of the polycrisis sweeping the world. It is emblematic of our situation that this disaster is unfolding less than 700 miles off shore from Florida, on the same island as the Dominican Republic, one of the economic success stories of the region. Though separated from North America by ocean, both parts of the island of Hispaniola are tightly linked to the US by a history of intervention and occupation and by mass migration. There are perhaps as many as a million people of Haitian descent in the United States and 165,000 in Canada.

The crisis in Haiti is often presented in the western media in naturalized form, as a question of earthquakes and hurricanes, “state-failure”, anarchy and disorder in their purest form etc. In the latest iteration the focus of reporting has been on “gangs” and “gangsterization” of the country. But one of the remarkable things about Haiti, given its dire poverty and the urgency of the crisis, is how active its civil society continues to be, even amongst the ruins. The crisis is therefore eminently political and it is both local and interconnected with wider global currents in politics and economics. The gangs in question are better thought of as minor warlords. They compete for control not only of logistics and transport, but also for territory and votes. They do so with and armory of weapons shipped in from the United States. And the immediate driver of the current crisis could hardly be more telling.

Modern Haiti is the product of a slave economy built to grow sugar. It was the original European solution to the “ghost acreage” question. Cheap sugar was the answer to the question of calories. Still today, Haiti’s crisis is a crisis of energy, but this time it is a question of energy imports not exports.

***

Overall consumption of fossil fuels in Haiti is very low. The majority consume tiny amounts. Only the top 10-20 percent have motor vehicles of any kind, generators, let alone regular power supply. But petrol and diesel are vital for what little power generation does take place and this secures basic transport and the logistics that maintain essential services like hospitals and connections between the countryside and markets. When farmers cannot get to market they sell by the side of the road. Of course sitting by the roadside only makes sense if there is traffic. Without petrol, no traffic comes. The result is comprehensive economic collapse.

The petrol and diesel that fuel Haiti’s hard-scrabble economy are entirely imported. Of late the main import terminal are two private docks in Port-au-Prince. Hitherto, for all the crises on the island, a trickle of petrol and diesel has always got through. Humanitarian relief could continue as well as rudimentary health services. The terrifying challenge of recent weeks is that this is no longer the case. What is happening is something close to total paralysis, or rather a desperate, restless search for any supplies that do become available. Whilst generators are still running to keep the network up, frantic cellphone messages send mobs of motorbikes and cars from one petrol station to the next. There is never enough. Fuel is mysteriously available on the black market for those with connections, deep pockets and guns. The prices are up to five times the official price. Even worse in the countryside.

In the embattled Cite Soleil neighborhood of the capital Port-au-Prince, where at least 100,000 people have been displaced from their homes by months of heavy fighting between rival armed groups, there is now a real risk of outright starvation with 65 percent of the population facing acute hunger.

How did it come to this? The answer depends on a combination of global forces, policy responses and local politics.

***

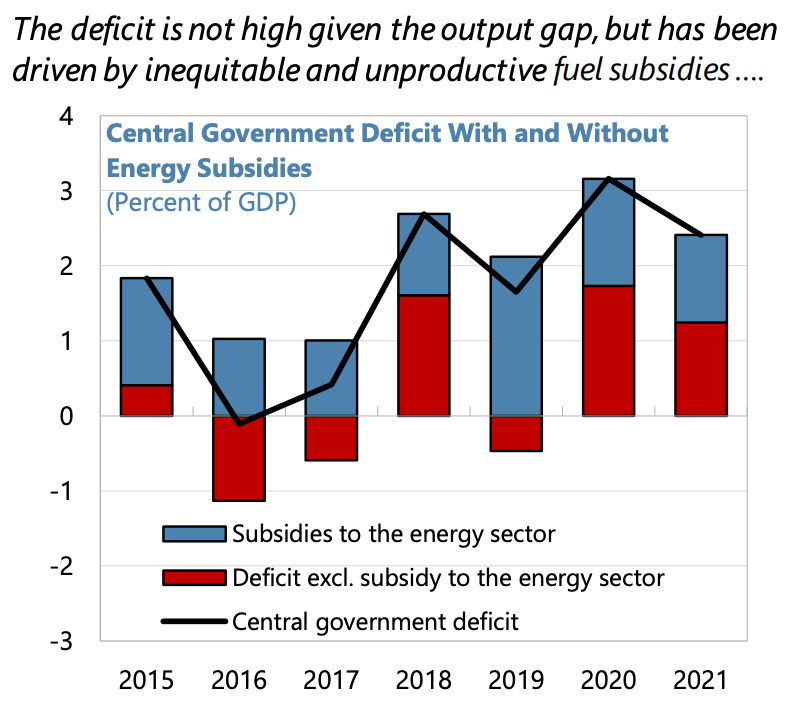

As a poor country, Haiti has been hard hit by the fluctuations in global energy prices. To cushion the shock one of the few things that the Haitian state does is to subsidize energy costs. In doing so it is far from alone, whether in the Caribbean or the world at large. But paying for energy subsidies takes a government capable of raising funds either through taxes or through borrowing. The Dominican Republic is now paying twice the rate for its borrowing that it did last year. It can still access credit markets. Haiti cannot. Since the subsidy is large and the direct benefit is felt above all by the better off, the IMF and other agencies have long argued for Haiti’s energy subsidies to be cut altogether.

In early 2022 the fuel subsidy was costing the Haitian government $400 million. As the IMF remarks:

Fuel subsidies have been absorbing at least one third of domestic revenues and crowding out productive spending on investment, health and education. They are also highly inequitable, with over 90 percent of the benefits going to the top 10-20 percent of the income ladder in Haiti. In this light, the authorities plan to prepare the groundwork to eventually tackle this issue. As a first step, they launched in April (2022) several social programs under the Programme d’urgence targeted to the groups affected by earlier fuel price adjustments.

Source: IMF

Like everywhere else in the world, cutting the subsidy makes sense, from a technocratic point of view. But it produces immediate losses for the minority who benefit. They tend to be influential and well-resourced, literally empowered. By way of transport and electricity prices, a subsidy cut sends a shockwave through the entire economy. Of course there are also off-setting benefits. If the Haitian government spent the $400 million elsewhere, many could benefit. But that begs the question of who the government is and how the freed-up funds would be allocated. If the cost saving is used not for new spending but to reduce the deficit and improve the “budget balance’, then the benefit could be something as abstract as a lower rate of inflation if the central bank is forced to monetize a smaller benefit. Few will see the connection or cheer.

The IMF economists are well practiced in these arguments and now recommend carefully calibrated social packages to offset any energy subsidy cut. But that balance is demanding at the best of times. It would have been a strain for Haiti even in better days. This is not the first time the issue has haunted Haitian politics. Under the peculiarly difficult circumstances of 2022 it is far more than the government in Port-au-Prince can handle.

***

The current configuration of politics in Haiti is defined by the US intervention of 2004 that removed Jean-Baptiste Aristide’s left-leaning populist regime from power and installed a UN-backed regime. The administration of President Latortue used considerable violence to impose its control and disempower Aristide’s party. This repression eased in 2006 after the election of René Préval who prior to being elected President in 1996 had also served as Prime Minister under Aristide. Préval pursued a strategy of development based on road-building and regional alliances, including an oil delivery deal with Venezuela. But he struggled to contain popular unrest over surging food prices, which exploded into mass protests in 2008 and in 2010, Préval’s government along with most of the rest of the Haitian state administration was buried under the rubble of the disastrous earthquake. The collapse of ordinary life precipitated a second major engagement by US forces which secured power for the brutal and corrupt government of Préval’s successor, Michel Martelly.

Martelly presented a glossy modern face to the outside world. He expressed support for policies ranging from universal education to health care, the rule of law, the creation of sustainable jobs, environmental protection and the development of Haiti as a destination for ecotourism and agritourism. He was well coached by the Clinton Foundation. It was also an open secret that the former singer, relied ever more openly on gang forces to secure power and hold any residual challenge from Aristide or the left in check. To function he also needed money. In line with its ecological agenda, in 2014, at the behest of donors and funding agencies, the Martelly government proposed to combine a major fuel price increase with greater spending on health and education. The result was to trigger a wave of strikes and a climb down on subsidies, which helped to put the outcome of the 2015 election in doubt.

After a tumultous period of political uncertainty, it was Jovenal Moise, designated by Martelly as his center-right successor, who took office as President in 2017. In 2018 he tried again to implement the energy subsidy cut. Citing the IMF, Moise proposed cutting fuel subsidies to qualify for $96 million from the World Bank, European Union, and Inter-American Development bank. Once again the proposal was met with a wave of protests that even Moise’s thugs could not contain. And the proposal was revoked.

In July 2021 Moise was assassinated. Unusually for a country full of gunmen, no one has been able to identify a clear “gang” connection. Instead, the killing was done by a squad of Colombians who announced themselves as DEA agents and several of whom were, in fact, former DEA informants. Their motives and their employer remains unclear. Weeks later Haiti was hit by another devastating earthquake. In the meantime, with the approval of the CORE group of international ambassadors, led by the US, the Americans and Brazil, Ariel Henry was chosen as President.

Henry, it is commonly acknowledged, lacks any real legitimacy. He was associated with the 2004 coup against Aristide and had been chosen by Moise shortly before his assassination to be his puppet prime minister. Haitian law enforcement officers have leaked documents that seem to tie Henry to Moise’s killing. Henry, of course, denies any connection. What is undisputed is that he has outlived the original Presidential term of his predecessor and canceled elections to the Senate thus leaving the Haitian government effectively without legitimacy.

It is against this backdrop of factious politics and the self-delegitimation of the Haitian elite that the fighting between armed groups, especially in Port-au-Prince surged to new levels in the second half of 2021. Once bustling neighborhoods have been reduced to empty shells. As never before, large parts of the city have come to resemble empty free fire zones.

But politics goes on. In February 2022, faced with mounting inflation Port-au-Price was rocked by large-scale demonstrations calling for a $15 per day minimum wage. Henry’s government agreed to less than $7.50 per day, a 54% increase, but far less than protestors were demanding.

Then, despite his lack of grip, Henry proceeded to follow the IMF’s advice and push through energy subsidy cuts. This has earned him tributes from international observers. The policy is a totem of international policy common sense. But in the Haitian context in 2022, it triggered an uprising.

Amid spiraling inflation and rising costs, the government announced Sunday that the price of a gallon of gasoline would rise from 250 gourdes ($2) to 570 gourdes ($4.78), while diesel prices would go up from 353 gourdes per gallon ($3) to 670 gourdes ($5.60). The price of a gallon of kerosene would rise from 352 gourdes ($3) to 665 gourdes ($5.57).

The reaction was immediate:

Young Haitians, frustrated by the lack of work and rising prices, took to the streets. The g9 coalition dug trenches to block access to the country’s largest fuel terminal, where it says it will stay until subsidies are reinstated. As a result, fuel has run out. Schools have not reopened after the summer holidays. Only three ambulances are working in Port-au-Prince.

It is G9’s blockade of the privately-owned Varreux oil terminal in Port-au-Prince that has precipitated the current existential threat to Haiti’s society

“Without that fuel, Haiti’s grid shuts down. So do the trucks that deliver food to supermarkets, the generators that refrigerate that food during the frequent power outages, and the factories and businesses that pay the wages that buy the food,” reports CBC News. The 12% of Haitian households with electricity are also affected because many of them rely on kerosene generators for power.

The warlord who has taken advantage of the situation to make a bid for power is Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier the head of the G9 Family and Allies. Though he loves the camera, he is a shadowy figure. An ex-policeman who was previously connected to Haitian Tèt Kale Party (PHTK) of Martelly and Moise, since Moise’s assassination Chérizier and G9 appear to have gone rogue. His forces routed Haiti’s frail police and seized control of significant chunks of territory including much of the shantytown of Cité Soleil and the polling stations there.

G9 acts with apparent impunity. In one particularly notorious case, Christella Delva, a 17-year-old student protester, was killed by the gang with a bullet to the head, while two young Haitian journalists, Tayson Lartigue and Frantzsen Charles, were also killed by G9 while returning from an interview with the parents of Delva. Several other massacres are attributed to G9 as it fought its way to the top of the pecking order.

With the blockade of the oil port crippling the entire country, it is hardly surprising that Chérizier has been singled out for UN sanctions. But you don’t grasp the complexity of the Haitian scene if you take the characterization of G9 offered by the Henry government and its international supporters at face value. From expert local commentators, there is an insistent strain of Haitian commentary that insists that BBQ and G9 are different. The G9 coalition earned its reputation not only through violence but also through imposing order in the Port-au-Prince slums during an uprising in 2019. Allegations of massacre leveled by the international community are refuted point for point. According to the man himself, BBQ owes his nickname to his mother’s fried chicken stand not to any liking for burning his opponents alive. Chérizier is a nationalist and names Papa Doc Duvalier as his main inspiration. Though this is routinely omitted by international media, the full name of the G9 coalition is the Revolutionary Forces of the G9 Family and Allies, or FRG9. In leading the blockade to topple Henry, Chérizier declared: “We have to mobilize and chase out all the politicians, the corrupt bourgeoisie that hold this country hostage.” Whether we credit it or not, Chérizier proclaims himself the leader of an armed revolution who declares indignantly that he could not have been involved in the massacres he is accused of because he would never use violence against people “in the same social class as me”. For a gang leader he has unusually capacious demands. Apart from an amnesty for himself and his men, according to Al Jazeera, G9’s demands:

President Henry’s resignation, positions in the cabinet, and the creation of a “Council of Sages” that has one representative from each of Haiti’s 10 departments, … The gangs’ demands are “a symptom of their power, but also a symptom that they may fear what is coming,” said Robert Fatton, a Haitian politics expert at the University of Virginia.

What G9 must fear is a major international military intervention. They boast that they are willing to stand and fight. In the short run there is not much that Henry as head of state can do about BBQ. The national police are out-gunned, though a shipment of Canadian armored vehicles may change that. In the mean time, the main fighting is done by other gangs. Most notable G-Pep, a longer established gang coalition associated with the opposition to Moise and Martelly. It has been reinforced by an alliance with another grouping known as 400 Mawozo, whose boss was extradited to the US by Henry’s government in May 2022. It surprises many Haitian commentators that G-Pep has so far escaped sanction. The extent of gang power is now such that in the event of any elections a majority of the votes would be cast in polling booths controlled by one or other of the armed factions.

It is his total lack of a domestic power base that leads Henry’s government to appeal loudly for outside intervention. He and Haiti’s ambassador in DC are only too happy to see the US, Canada and Mexico lobbying at the UN for action against G9. But when the idea of UN action was mooted it was clear that there was no UN mandate for intervention. Russia expressed its unwillingness to go along and the motion was dropped. That accounts for the incongruous appearance in demonstrations in Port-au-prince of the Russian flag. The logic of the new non-alignment is spilling into Haiti’s streets. As comments by President-elect Lula have made clear, the suspicion towards any alignment with the US against Russia, is widespread in Latin America. It is worth noting, however, that Haiti is one of the places where no one on the left celebrated Lula’s victory. He is remembered there for Brazil’s disastrous leadership of the UN intervention force after 2004.

There is much talk in Haitian commentary about America’s hegemonic ambition in their country. Haitians follow US strategy closely and have taken note – far more han many commentators in the US – of the bipartisan Global Fragility Act that Donald Trump signed into law in December 2019. It was a bipartisan effort by US development policy experts to craft an alternative to China’s One Belt One Road. it commits the US to long-term investment and stabilization programs over a long-term time horizon. Haiti along with Libya were proposed as the first candidates for this policy. Approval has been held up in the Senate by Republican opposition. For the Haitian left this is a new iteration of America’s designs on their country.

In fact it seems wildly implausible to imagine that the Biden administration would want to put boots on the ground in Haiti. In 1994 Biden broke with Clinton to opposed intervention in Haiti. Washington is primarily concerned to avoid a humanitarian disaster and possible spillover. The Biden team certainly doesn’t want a repeat of the disgraceful scenes of September 2021 when thousands of Haitian refugees were caught on the Texas border.

The solution? Washington would dearly like Canada to intervene. Canada is carefully sizing up the problem.

Informed judgement seems to be that any attempt at a full-scale international intervention would most likely end disastrously. To have any hope of success, foreign aid needs to be carefully targeted and above all it must have solid local backing. Though the CORE group and Washington continued to deal with Henry, if there is one thing that is clear it is that Henry cannot provide that solid political platform. The problem is not that there is no civil society in Haiti, but that it is too vociferous and complex and mobilized. To resolve that problem Henry wants to push for early elections but in the midst of widespread hunger and a cholera outbreak, that seems entirely unrealistic. It would mean handing control of the outcome to the armed groups.

US experts like George Fauriol of CSIS tend to talk about the need for “Haitian political consensus”. More realistic than a consensus is the call to assemble a powerful coalition of local backers. The obvious forum is the multi-party Montana Accord which is further tied to the Protocole d’Entente Nationale (PEN), a coalition of some 70 political organizations and groups. Unlike Henry and Washington they have called for a protracted transition process, what leading US experts refer to as “a plausible transition formula out of the crisis”.

The danger in such a protracted process is that the crisis escalates. And in the mean time the political coalition sustaining the transition effort fractures. What spooks many commentators on the Haitian left is the closeness between the Montana Accord and agencies like the US National Endowment for Democracy, that were tied to the Aristide ouster in 2004. Since the beginning of the year the main representatives of the Haitian left including Aristide’s party have broken with the Montana grouping.

Stymied in every direction the clock continues to tick. Violence, insecurity, hunger and now cholera too, are wracking the country. Will it take a full-blown humanitarian catastrophe with people starving to concentrate minds? Will even that be enough?

***

There is little doubt that the main concern in Washington is a refugee crisis. As the Economist put it:

Mr Biden’s government was slow to act, says Robert Maguire of George Washington University in Washington. Its main concern is the rising number of migrants. Some 50,000 were apprehended in the United States between September last year and this August, 12 times as many people as the same period two years ago.

It is telling that the first reaction of the US, rather than engaging with grouping in Haiti like the Montana Accord, has been to send a coastguard vessel to patrol Haitian waters.

Haiti’s own ambassador to DC, an ally of Henry, is unafraid to spell out the threat. Send armed force to back the current regime or face a refugee wave from a country that is only 700 miles from Florida.

But well before the US, the Dominican Republic will feel the effects of the crisis. The gap in living standards between the DR and Haiti has long been large. It is now a gulf. Over that gradient, people move one way. The total number of Haitian workers in the Dominican Republic is uncounted. It is clearly in the many hundreds of thousands. Meanwhile, as people go one way, petrol and diesel go the other.

The Dominican Republic, like Haiti, imports its fuel. Unlike Haiti, faced with the impact of what President Luis Abindar calls a “war-time economy”, the DR has spent over $1 billion on food and energy price subsidies, even as the yield on its sovereign debt has nearly doubled from 4.4% to over 8 %.

On the border that means that there is a huge price differential between low-cost DR petrol and the spiraling prices in Haiti. Petrol bought at the subsidized pricer of $5 a gallon in border cities in the Dominican Republic, when smuggled to Haiti fetches as much as $50 a gallon. Unsurprisingly, lines of petrol buyers are forming in the DR, a visible manifestation of the tax pesos that will be heading across the border.

At the meeting of the OAS on September 16 2022, President Luis Abindar put the situation in dramatic terms: “For the Dominican Republic”, the “low-intensity civil war” in Haiti, “is a matter of national security. I want to repeat it so that it is engraved in the memory of this solemn session in the Hall of the Americas: the crisis that overflows the borders of Haiti is a threat to the national security of the Dominican Republic”. For many this was a gross exaggeration designed principally to provide a justification for international intervention. So long as the Haitian crisis remains domestic it is harder to justify calls for international action. But the escalation of anxiety in the DR is real.

With Dominicans marching in protest against Haitian migrants, members of Abindar’s own government such as Economy Minister Pavel Isa Contreras have warned against “inflammatory”, anti-Haitian, anti-black “discourse that points in a racist line”. Liberals in the DR are acutely conscious of the bloody history of the border region, where in 1937 the Dictator Rafael Trujillo unleashed a racist pogrom that claimed tens of thousands of Haitian lives.

What then is the solution of those in the DR concerned to preserve the balance and avoid an escalation into outright and open racial antagonism? The government of Luis Abindar and Economy Minister Pavel Isa Contreras is building a wall. When completed it will be the second largest in the America’s after the US border wall with Mexico.

Of course, the DR’s enlightened spokespeople hasten to add that this is not just an exclusion measure. It is not meant to seal the border, but to regulate it. It is vital for regional economic development, from which everyone profits, to ensure that Haitian chaos does not spill over to the DR.

Meanwhile, as Jim Wyss at Bloomberg points out, responsibility for the violence and poverty that wrack Haiti extends far beyond the island of Hispaniola.

The wall is also, at some level, a reproach to an international community that has spent billions in Haiti but has been unable or unwilling to alleviate the growing humanitarian crisis.

The effect is that whilst Port-au-Prince is ground to rubble, Haiti’s misery is being concreted in. This then is the answer to the polycrisis on Hispaniola, the Island where the violence of modern history first reached the Americas. Put up walls. Erect check points. Control the flow.

****

I love writing Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.