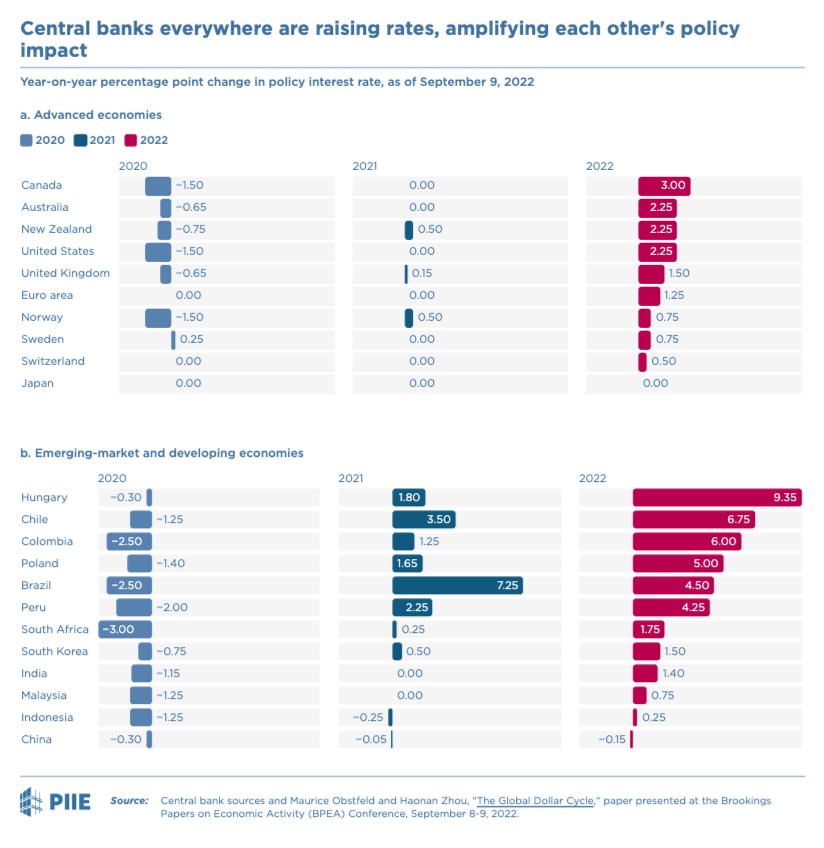

In response to the surge in prices that began in earnest in the summer of 2021 central banks all around the world are hiking interest rates. When taken together, a series of national policy moves add up to the most widespread tightening of monetary policy since the start of the fiat money era in the early 1970s.

Source: World Bank

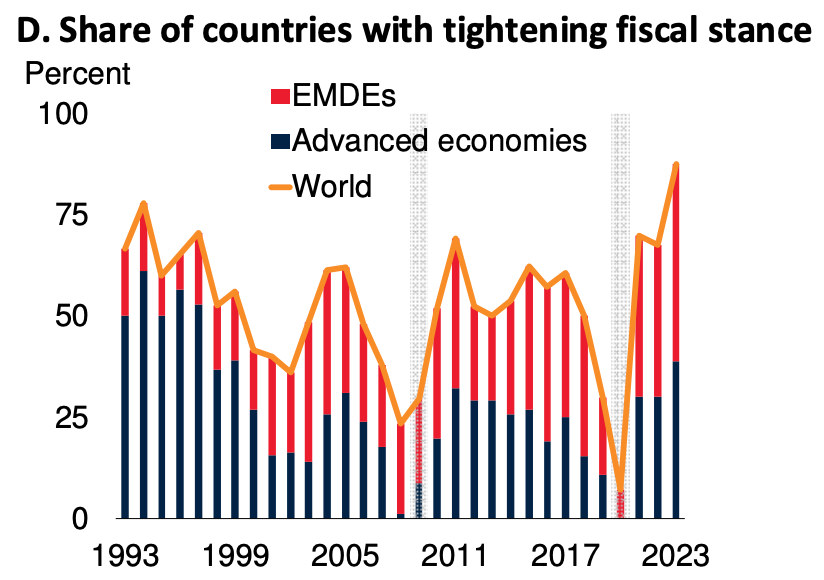

The tightening of monetary policy is compounded by a similar shift in fiscal policy. This attracts far less headline space than interest rates, but it too is unprecedented. The share of countries that are tightening their fiscal stance is greater today than it was during the global austerity drive after 2010, or in the heyday of the Washington consensus in the 1990s.

Source: World Bank

The panic around inflation should not lead us to underestimate the significance of this shift. It may not be the Volcker shock. The level of real interest rates – nominal rates adjusted for inflation – remains low. But this is the most dramatic shift in the stance of policy we have witnessed since the 1980s. The risk is that it will be excessively contractionary and will trigger a worldwide recession. The US has been in technical recession for two quarters. Under the impact of Putin’s war, Europe is teetering on the edge of a true contraction. China’s situation is more than fragile. So serious is the risk of global recession that energy markets are already responding. Oil has sold off. Brent crude is now trading around $90 for the barrel, down from $120 as recently as June.

Nor should we exaggerate the degree of freedom exercised by decision-makers. The dramatic surge in interest rates around the world is mutually conditioning. Notionally, in a world of relatively flexible exchange rates, countries ought to have a degree of freedom in relation to US policy. But this underestimates the force of the global dollar cycle. Once the Fed starts hiking, others have little option but to follow suit or face severe currency devaluation, which, by raising import prices, will stoke further inflation. And though we think of the world economy as being one of flexible exchange rates, in fact, many currencies, from the Bahamas to Hong Kong, are pegged more or less explicitly to the dollar. As Shang-Jin Wei, former chief economist at the Asian Development Bank points out:

For the 66 smaller economies that peg their currencies to the US dollar – especially those without significant capital controls, like Hong Kong, Panama, and Saudi Arabia – local interest rates tend to rise automatically whenever the US raises its interest rate, even when higher rates are harmful to their economic prospects.

The pattern of interest rate increases is both strikingly uniform and sharp.

Source: Peterson

Though there is interdependence of central bank decision-making, what we have not seen so far is any effort at explicit coordination. The lack of coordination is a problem because if interest rate decisions are taken in isolation from each other this may well lead to an excessive tightening. As Shang-Jin Wei explains:

an interest-rate hike by any major central bank has the effect of exporting inflation to other countries, forcing other central banks to raise interest rates more than they otherwise would have done. For example, when the Fed raises its interest rate, if the BOE and the ECB do not respond, the pound and the euro would depreciate against the US dollar, leading to higher import prices and adding to the already high inflation. If the BOE and ECB respond by further raising their interest rates, they export a bit of extra inflation back to the United States and to other economies. The result is an interest-rate spiral that is more damaging to world output and employment than these countries may wish to see collectively.

As former IMF chief economist Maurice Obstfeld explains in a post for the Peterson Institute once we allow for interaction between economies, the effect ought to be to moderate interest rate increases rather than to amplify them. Obstfeld’s arguments runs by way of slack in goods markets and not exchange rates. A central bank that raises interest rates hopes to slow its economy down and raise the level of slack. In a globalized world that has effects not just at home.

The proliferation of global value chains and global trade integration, reflecting a big increase in the share of international trade due to intermediate products, makes it plausible that foreign slack could lower import prices with knock-on effects for inflation. If so, inflation could depend more on foreign and less on domestic slack, attenuating the Phillips relationship between domestic inflation and purely domestic slack.[5] If we accept the hypothesis that global slack matters for domestic inflation, then in current circumstances, it suggests that each central bank should be less rather than more zealous in raising interest rates. The reason is that central banks abroad, through their own inflation-fighting efforts, are also helping to dampen inflation at home. If central banks do not take into account that spillover in calibrating their own needs for higher interest rates, they will each overdo monetary tightening.[6]

The sharp reaction in oil prices already suggests the power of this effect. As energy markets digest the growing probability of a global recession and oil prices plunge, that will have an immediate effect on imported inflation in many economies around the world. With falling global energy prices, central banks have less need to take radical action to stop the inflation.

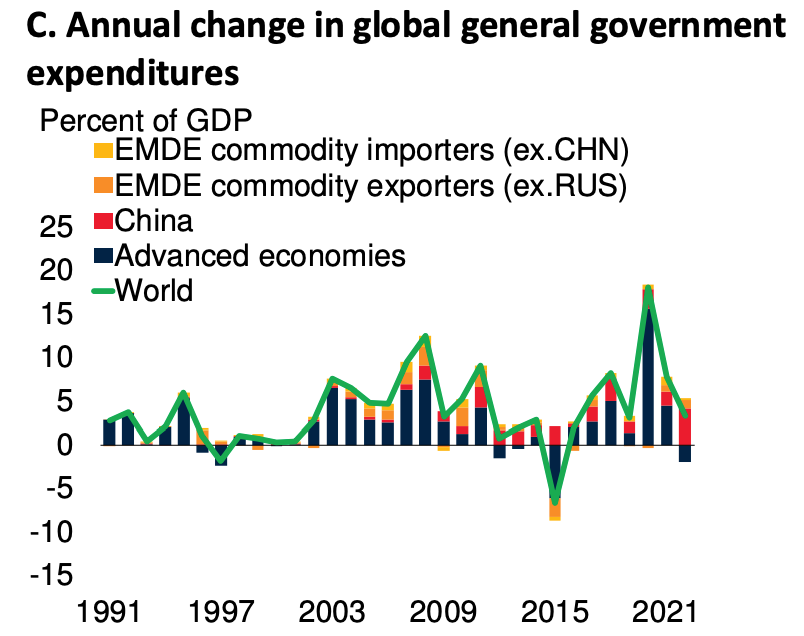

Nor, in 2022, is it only monetary policy that is set in contractionary mode. On the fiscal side, growth in government spending is being retrenched.

Source: World Bank

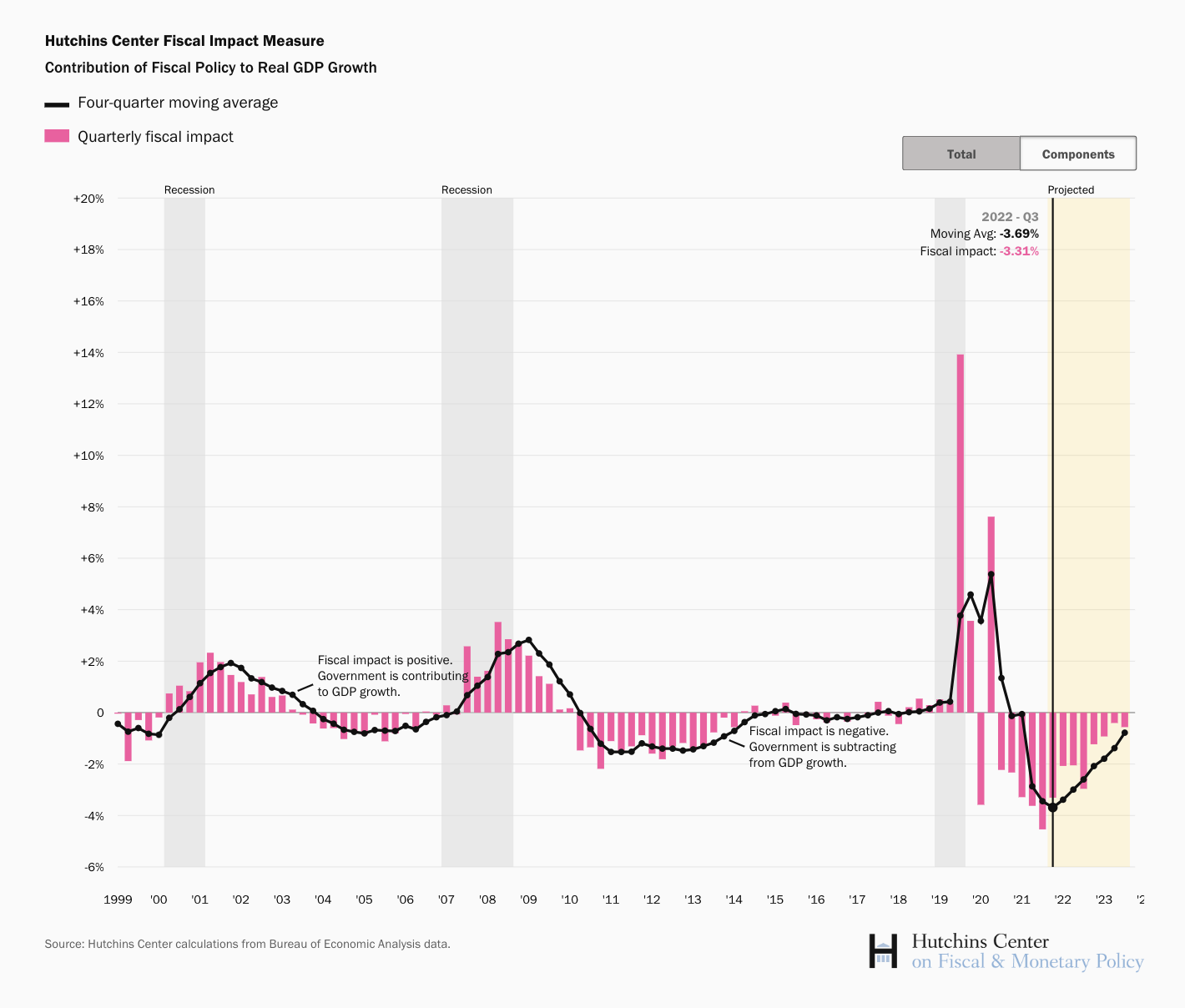

In the US, the biggest engine of global demand, fiscal policy is now delivering a severely negative shock. According to the calculations of the Hutchins Center in Q3 2022,

Fiscal policy reduced U.S. GDP growth by 4.6 percentage points at an annual rate in the second quarter of 2022, the Hutchins Center Fiscal Impact Measure (FIM) shows. The FIM translates changes in taxes and spending at federal, state, and local levels into changes in aggregate demand, illustrating the effect of fiscal policy on real GDP growth. GDP fell at an annual rate of 0.6% in the second quarter, according to the government’s latest estimate.

In 2020 during the COVID crisis, when fiscal limits were jettisoned and it seemed that government spending had been unchained, many of us warned that it would not be until several years after the crisis that we knew whether anything had really changed in fiscal politics. After the 2008 crisis it was in 2010 that the austerity wave began. In 2022, right on cue, the pivot to retrenchment has arrived.

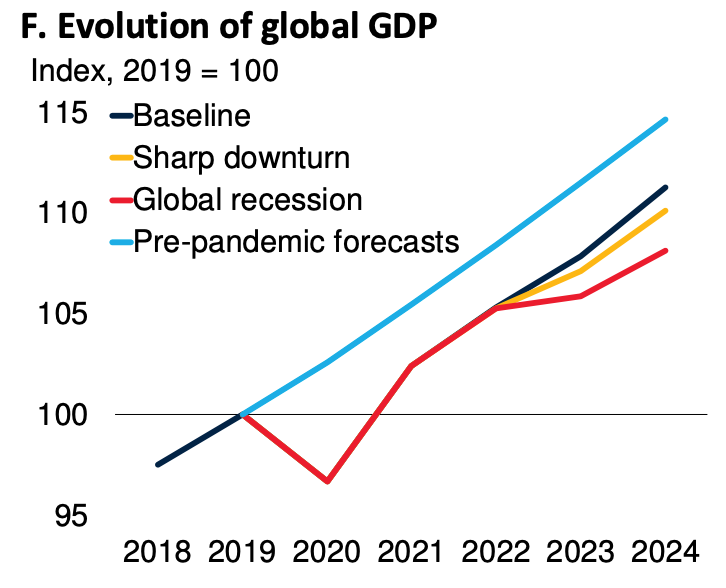

If you put the combined effect of monetary and fiscal policy together, you arrive at very grim scenario for the world economy. A modeling exercise by Justin Damien Guénette, M. Ayhan Kose, and Naotaka Sugawara of the World Bank, suggests that in the event of a recession, global GDP would not reach the level predicted on the pre-COVID trend for 2024 until somewhere around the end of the decade.

Source: World Bank

It is encouraging against this backdrop that there are notable exceptions to the contractionary tend. The Bank of Japan is holding the line on yield curve control and allowing the yen to depreciate against the dollar. In light of Japan’s decades long struggle with deflation, the BoJ is happy to accept the inflationary pressure that the devaluation generates.

The Peoples Bank of China is also bucking the trend. Indeed, last week it actually cut rates. But that just goes to show how serious are the worries about China’s economy. It faces not only a dramatic slowdown in growth. The PBoC is also deeply concerned about financial stability. The deliberate bursting of the property bubble threatens to bring the whole house down.

In 2015 the last time the Chinese economy was in serious trouble, the Fed deferred the interest rate hike planned for September 2015 until 2016. Even if talk of a deal between the Fed and the PBoC – the so-called “Shanghai Accord” – exaggerates the degree of cooperation, the Fed was quite explicit in arguing that it did not need to tighten in September 2015 because the deterioration in global financial market conditions triggered by the crisis in China was doing the work of tightening for it.

What are the options today? As MauriIn Obstfeld remarks:

In principle, central banks could avoid excessive monetary tightening without explicit coordination simply by accurate forecasting of each other’s policy moves and their global effects (The 2015 scenario, AT). Just stating this computational problem, however, illustrates how difficult it might be compared with proactive direct consultation, which at the very least would provide more transparent guidance. Moreover, joint action by central banks coupled with clear public communication could usefully moderate inflationary expectations globally. Central banks have coordinated to good effect during financial crises that raised deflationary threats, but the current inflationary conjuncture equally merits such an approach. … Now is the time for monetary policymakers to put their heads up and look around. They should take into account how the forceful actions of other central banks are likely to reduce the global inflationary forces they jointly face. … If central banks collectively pursue a gentler tightening path, however, at the same time communicating their coordinated intentions clearly to the public, they will avoid excessive sacrifices of output and employment beyond what is needed to bring inflation down.

After all the speculative talk about possible alternatives to the US currency with which 2022 began, we now face a serious test of how the actually existing dollar system works. Explicit coordination in interest rate setting is perhaps a tall order. But, if an uncoordinated surge in interest rates, driven by the Fed’s determination to control US inflation leads to a global recession, it will raise real questions about the system’s functionality.

And it is not just monetary policies that need to be coordinate. We need to keep in mind the combined impact of monetary and fiscal policy together.

We should not succumb to the blackmail of inflation scaremongering. We should call the current policy conjuncture by its name. It is the most concerted effort to slow down growth and employment in the interests of monetary stability that we have seen since the 1980s. In 2020 we saw the remarkable power of coordinated monetary and fiscal policy in keeping the economy afloat. In 2022 in the US and many other countries we are now seeing coordination in the opposite direction, with both monetary and fiscal policy pushing towards contraction. This is not a combination with which we have much recent experience, notably in the United States. We should be clear about the risks that we are running.

A global recession would be an expensive waste. A generation of young people whose education was blighted by COVID lockdowns, will face a closed labour market. Nor is that mere speculation. It is already a reality in the largest labour market in the world, in China where youth unemployment is hovering dangerously close to 20 percent. Outside the core, a global recession may well snap some of the weakest links in the dollar chain. Those who advocate a tightening of fiscal and monetary policy in the name of stopping inflation, do so because they fear a build up of inflationary momentum. That risk may be real. No less real, however, are the costs of the contractionary policy mix being applied now. If there is a possibility that the inflationary wave has already broken and that the contractionary policy mix already applied may be enough that possibility should weigh heavily in the balance. As Mohamed El-Erian warned in May we should beware a world with “little fires everywhere”.

****

There are three subscription models:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

Several times per week, as a thank you, all paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.