Central banks around the world are under pressure. Surging prices stoke fears of inflation. Central bankers, who commonly define themselves as guardians of price stability, feel forced to react. Interest rates are their preferred tool. Higher rates take steam out of the economy. That should lower inflation. The price is pain for borrowers and the risk of a recession and rising unemployment

The choice for central bankers is easier where price increases are taking place across many sectors, meaning that the economy is undergoing a general inflation. This includes wages rising along with prices. The correlation between wages and prices should be regarded neither as anomalous nor as a dangerous “second round effect”. It should, in fact, be definitional of a general inflation. Wages are the price of labour. If wages are not rising along with other prices, then you are not dealing with a general inflation at all, but rather a one-sided redistributional push by capital at the expense of labour. A truly general inflation will commonly go hand in hand with a relatively strong economy with low unemployment.

In this respect there is a big difference between the situation on either side of the Atlantic.

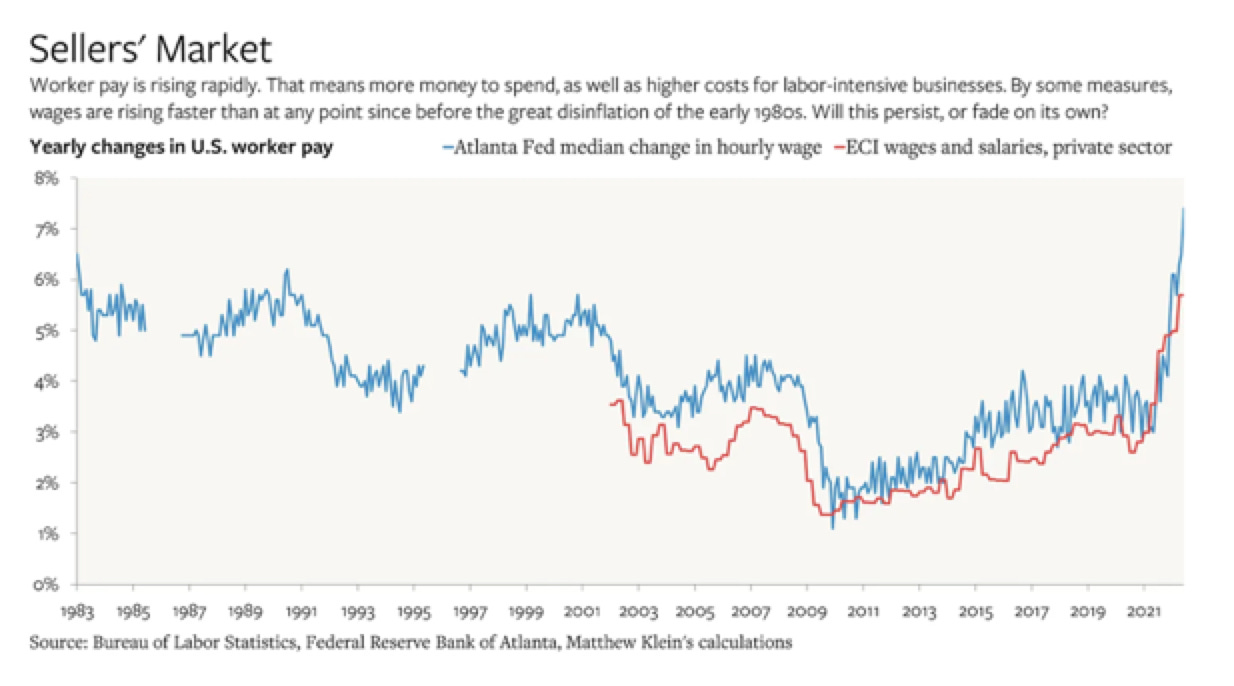

In the US, the Fed is facing a general inflation, modest in pace, but broadly based. Price increases are not uniform, they never are. But they now extend from bottleneck sectors, such as energy and food, to rents and house prices. Wages are also rising broadly in line with prices.

Source: Matt Klein’s Overshoot

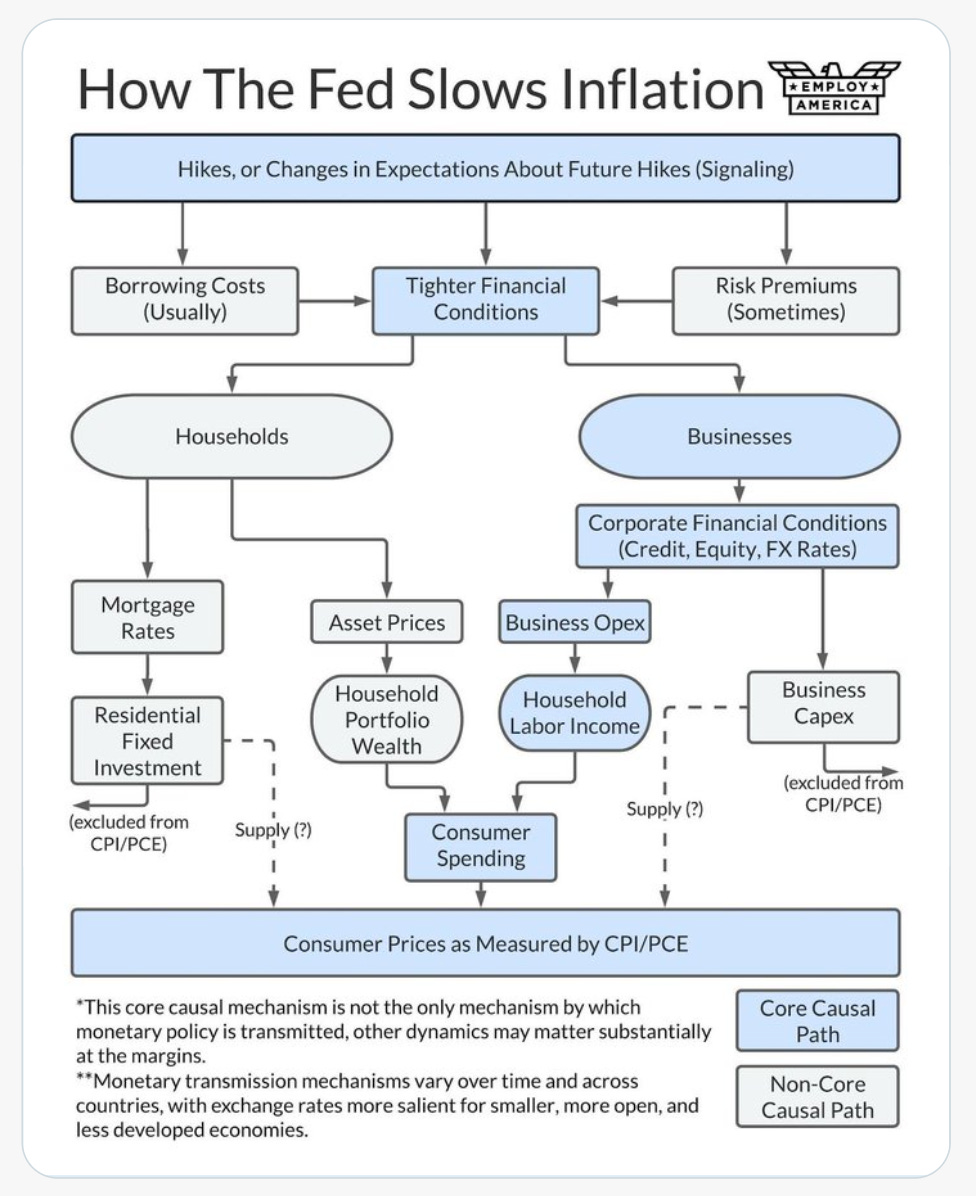

To respond to this broad-pressure pressure, the Fed’s interest rate increases are the conventional answer. This graphic from Skanda Amarnath of Employ America, nicely illustrates the main transmission mechanisms.

The transmission mechanism, mainly by way of the labour market and unemployment, is blunt force. It prompts one to think about alternative policies that might work more efficiently and with less labour market impact. But given the nature of US inflationary pressure right now, the Fed’s hike will likely work. The question is how sharp and sustained the rate hikes should be and what price businesses and employees will pay for the resulting slowdown. The Fed is still hoping for a soft landing.

One thing that the Fed is not worrying about, at least in the near-term, is financial stability. Equity markets have not liked the rise in interest rates. Some debtors have felt the pinch. There are unresolved issues in the architecture of the US Treasury market. As the Fed had ended its asset purchases, liquidity in the Treasury market has dried up. But there is little reason to fear a systemic financial crisis of the type that occurred in 2008.

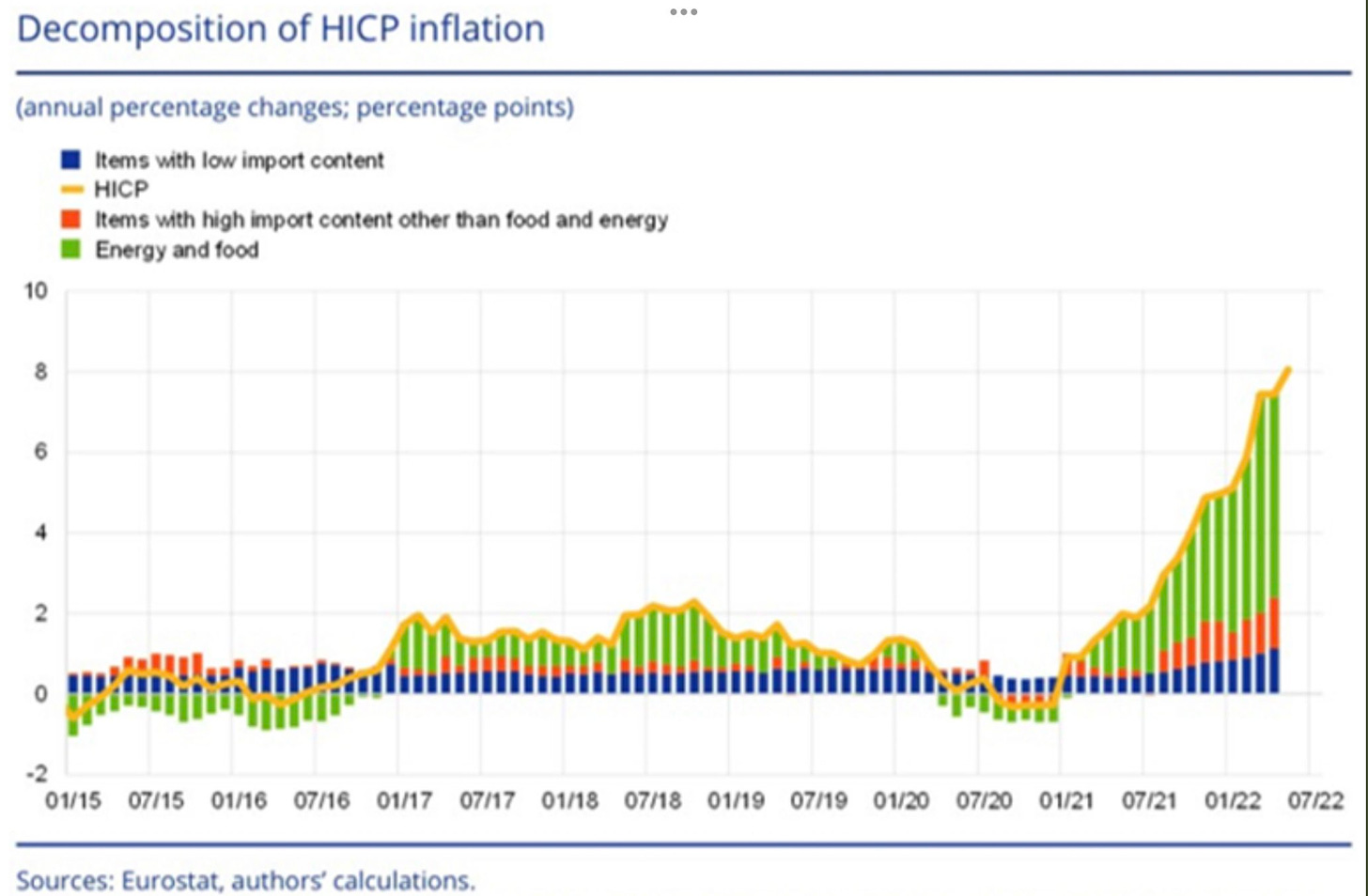

The situation in Europe is quite different. Price increases are far less broad-based. The proper description for what is happening in Europe is really an energy and food price shock rather than a general inflation.

The energy price shock is sufficiently serious, to threaten a socio-political crisis as household expenditures and business budgets are wrenched out of balance by the price of gas and electricity. But to insist that this is an “inflation” problem and thus properly the domain of central bank interest rate policy is, to say the least, question-begging. What good will interest rate increases do in slowing down a surge in gas prices caused by the uneven COVID recovery, Putin’s war in Ukraine and the lack of integration in the global gas market?

The ECB’s difficulties are compounded by the fact that the European economy is far less robust than that of the US. Many indicators suggest that Europe is already sliding towards a recession, with falling real wages and the energy shock leading to a collapse in confidence. And to make matters worse, any interest rate hike by the ECB risks unleashing the demons of Europe’s sovereign debt market. And this pressure is all the more worrying given the fiscal demands generated by the energy crisis.

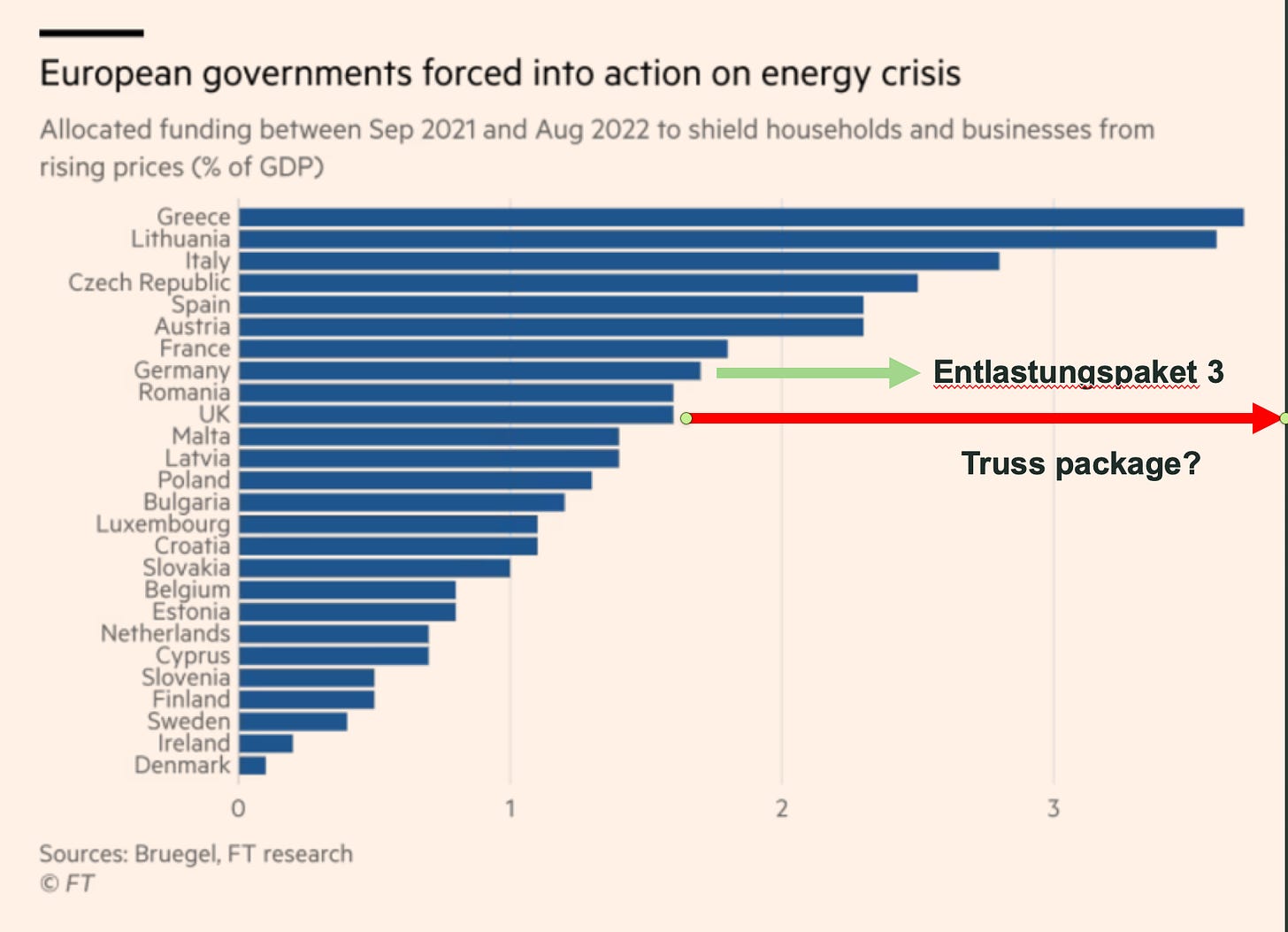

To respond to the energy crisis Europe’s governments are engaging in price stabilization and subsidy packages costing several percentage points of GDP.

Though they hope to claw much of this back in excess profit taxes and other levies, a surge in government spending will put pressure on budgets and make bond markets nervous. Italy’s debt levels were already causing concern before Putin launched his war. It won’t help matters if the ECB starts driving up rates. On the other hand, if the ECB does nothing, it will find itself under withering attack from conservatives questioning its commitment to fighting inflation. Their demands for action will be all the more vociferous because over the summer the ECB put in place the so-called Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), which is notionally supposed to protect the market for Italian debt against unwarranted sell-offs.

So what is the ECB to do? It is damned if it acts and damned if it doesn’t. To characterize this uncomfortable situation, Daniela Gabor in a typically brilliant piece in the FT, coins the phrase “Zugzwang central banking”.

Zugzwang is the anomalous situation that can arise in a chess game when the requirement to make a move becomes binding. Normally, it is advantage if it is your turn to make a move. It gives you the initiative. But, particularly towards the end of a game, you can find yourself trapped in a situation in which every possible move makes your position worse, so that the requirement to make a move becomes a curse. It can even lose you the game. That, Gabor suggests, is the situation of the ECB.

As she sees it, the ECB has four possible moves. Three of these are conventional central banking policies: raising rates, Quantitative Tightening, holding rates. The fourth, Gabor adds mischievously, is to admit “regime defeat”.

On Gabor’s reading the ECB in 2022 faces not only a policy dilemma but an impasse that ought to put in question the model of central banking as we have known it since the 1990s.

Under the financial capitalism supercycle of the past decades, inflation-targeting central banks have been outposts of (financial) capital in the state, guardians of a distributional status-quo that destroyed workers’ collective power while building safety nets for shadow banking. The limits of this institutional arrangement that concentrates (pricing) power and profit in (a few) corporate hands are now plain to see. …..

What if Zugzwang is that last stage of a central banking paradigm, when it implodes under the contradictions of its class politics?

Let us follow Gabor’s train of logic to see how she arrives at this striking conclusion.

Of the three conventional policy options for the ECB, none looks attractive.

On September 8, the ECB followed the Fed in hiking interest rates by 75 basis points. It would be kind to describe this as a symbolic gesture. The interest rate hike will do nothing to stop the price rises that ostensibly justify it. And if it were honest the ECB would admit that it has no model that would suggest otherwise. The ECB does not really believe that an interest rate increase will curb energy price inflation. So the move is best interpreted as political. It is a concession to the conservative claque that is demanding action. How much more action they will extract remains to be seen. If this first increase is the harbinger of a full-blown counterattack by Europe’s monetary conservatives, prepare for a serious recession. That may do something to slow down price increases, but given the energy price shock, the economic price would likely be terrible.

Other than interest rate increases, the ECB could also engage in quantitative tightening (QT). It could start rolling off the trillions of euros in Eurozone sovereign debt it acquired in the course of the quantitative easing-programs (QE) of 2015 and 2020-22. QT appeals to hawks because it reverses QE – the talisman of unconventional monetary policy. Reverse QE and you slay the beast, or so the story goes.

It is a high-risk strategy. As Gabor points out, QT would

pile pressure on to sovereign markets that have already delivered some tightening of monetary conditions. Italy’s 10-year yield now hovers around 4 per cent, a 2 percentage points spread to the German Bund, at a time when eurozone countries need aggressive fiscal and structural policies to contain the possibility of future persistent supply shocks.

Such pressure would be painful and politically explosive, but it might actually be welcomed by überhawks. For them squeezing the fiscal space of Europe’s government is precisely what the ECB should be doing. They welcome a return to the cat and mouse game that Jean-Claude Trichet played, when he was head of the ECB during the Eurozone crisis in 2010 and 2011. Trichet would buy bonds only when he judged that national governments had done enough by way of “reforms”. For the hawks this counts as wise central banking, forcing the onus for action onto Europe’s national governments.

What this strategy ignores, is not only the attritional impact on European democracy, but the risks to the wider financial system emanating from a nervous sovereign bond markets. As Daniela Gabor has done more than anyone else to show us, the European sovereign debt is not just a means of funding government. Sovereign debt is collateral for repo transactions and thus for private credit. As Gabor remarks in the FT:

In turning European states into a collateral factory for private finance, the founding fathers did not consider the financial stability implications for the ECB.

… the eurozone’s macro-financial architecture is wired to amplify volatility in sovereign spreads to the German Bund, via the €9tn repo market. This wholesale money market provides the plumbing for private credit creation, both on bank balance sheets and through securities markets. It was designed — by the ECB and the European Commission — to mainly rely on eurozone sovereign bonds as repo collateral. Yet we know from the eurozone sovereign debt crisis that repo collateral valuation means cyclical market liquidity in eurozone sovereigns except Germany, threatening liquidity spirals that only the ECB can prevent. Liquidity spirals, it is worth remembering, or not just bad for eurozone governments, but also for private institutions that use those bonds as collateral.

The irony is that überhawks imagine that quantitative tightening will allow them to escape from the unconventional policies of the past, whereas it was in fact Trichet’s reckless gamesmanship that set in motion the doom-loop in European sovereign debt markets that forced Mario Draghi in 2012 to make his “whatever it takes” speech. Ten years later that logic leads on to the Transmission Protection Instrument, with which the ECB seeks to contain Italian sovereign spreads. The ECB cannot wish aways these financial entanglements and engage in sudden quantitative tightening without risking severe repo market disruption.

Without radical structural reform we are prisoners of decisions taken in the 1990s. In the heyday of neoliberalism, Europe’s monetary policy-makers built a market-based model of central banking. They integrated private short-term credit markets, above all the repo market, into the operations of the ECB. This linked the stability of financial markets and institutions umbilically to sovereign debt. Destabilize the latter and you put the former in jeopardy. The necessary measures, such as QE or the TPI, may appall conservatives but, for their own sake, they cannot be trusted with monetary policy. They know not what they do.

The right technocratic choice, Gabor suggests, would be for the ECB to do nothing. For the past year, the ECB deserves credit for doing precisely that. It sat tight

… in the hope that supply shocks that it cannot control would dissipate, and inflation would once again behave as its models predict.

But that sensible policy of inaction has fallen victim to circumstances.

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, coupled with the reluctance of European governments to act decisively with energy price caps, have left the ECB as a convenient scapegoat. Scapegoating invariably turns dovish central bankers into hawks, particularly when their peers elsewhere act as obedient vassals to the dollar hegemon. Indeed, monetary historians will marvel at that brief period when European politicians believed so much in the euro’s potential to unseat the US dollar … With that illusion behind us and the euro below parity, the ECB is just another central bank trapped in the global dollar financial cycle, prey to facile comparisons with other central bank interest rates.

How far the Fed was really a significant factor in the ECB’s decisions will in due course, be revealed by the historical archive. Personally, I don’t find it a particularly persuasive interpretation for the ECB’s September decision. But this passage by Gabor contains the germ of another idea that I did hear actively discussed in Europe last week.

Perhaps the game that the ECB is playing is not the Trichet-style game of chicken in which the ECB withholds support from sovereign bond markets until Europe’s governments adopt fiscal austerity. Perhaps the game that the ECB is playing in 2022 concerns energy markets. It is clear to the central bankers as well as everyone else that the core of Europe’s “inflation” problem is in the markets for gas and electricity. The infrastructure and regulation of those markets is dysfunctional. Fixing those problems is the route to price stability. That is a task for national governments not the ECB. The ECB, however, does need to be seen to be doing something. So it will raise rates, inflicting pain that it knows is largely irrelevant to the issue at hand, until governments commit themselves convincingly to reforming energy markets. That too is a hypothesis, but it makes more sense to me than believing that the ECB is particularly concerned about parity with the dollar.

Whatever the explanation for the ECB’s recent interest rate decision, what the ECB leadership has forsaken is the coordination of monetary and fiscal policy that it adopted in reaction to the macroeconomic shock of 2020. At the time Gabor propounded the idea that we were witnessing a revolution in economic policy without revolutionaries. Responding to Gabor, in my book Shutdown I argued that what we were witnessing was not so much a revolution without revolutionaries as a gigantic effort at conservative stabilization, under the slogan that for everything to remain the same, everything must change.

In 2020, it was concern for the stabilization of the all-important US Treasury market that drove the Fed into gigantic bond purchases that then flanked the dramatic fiscal stimulus measures launched by Congress. In the EU we saw an unprecedented combination of open-handed bond buying by the ECB, national fiscal activism and the innovative Next Gen EU recovery program funded by bonds issued by Brussels. All this took place under the sign of low-flation. The main worry was not inflation but the risk of sliding into deflation.

Since the summer of 2021, the surge in prices has flipped the terms of the policy argument.

In the US, monetary and fiscal policy remain coordinated. But now, both fiscal and monetary policy are driving in an anti-inflationary direction. It is emblematic that the core of Biden’s climate agenda was stripped out of the $3 trillion Build Back Better program and reborn over the summer of 2022 as the Inflation Reduction Act.

In Europe policy-makers are facing a more conflicted and difficult set of choices. At Jackson Hole, Isabel Schnabel announced that what the ECB was facing was a fundamentally new environment. No longer the Great Moderation welcome by Ben Bernanke in the early 2000s but a new “great volatility”. Taking up that idea Gabor goes over to the offensive calling for a new synthesis of fiscal and monetary policy under a progressive sign.

“If the climate and geopolitical (shocks, sic) of 2022 are omens of Isabel Schnabel’s Great Volatility that most central banks and pundits expect for the near future, then macro-financial stability requires new framework for co-ordination between central banks and Treasuries that can support a state more willing to, and capable of, disciplining capital.”

In other words it is time to tackle the fragility of the European sovereign debt-repo market head on and on that basis to double down on the synthesis of monetary and fiscal policy that first became visible in 2020. That is a tall order and Gabor knows it. Who would initiate such a radical restructuring? One should hardly expect the ECB to do it.

such a (new) framework would threaten the privileged position that central banks have had in the macro-financial architecture and in our macroeconomic models. The history of central banking teaches us that policy paradigms die when they cannot offer a useful framework for stabilising macroeconomic conditions, but never at the hands of central bankers themselves.

No government in the Eurozone or the EU is likely to push such an agenda.

If there is a government that might be willing to put in question the status of an independent central bank, it would seem to be Liz Truss’s new administration in the UK. Whilst she was running for the Tory leadership Truss challenged the Bank of England’s autonomy in making interest rate decisions. She has since backed away from that heresy. But Kwasi Kwarteng, her choice as Chancellor, has called for “co-ordination across monetary policy and fiscal policy”. If both fiscal and monetary policy were set in an expansive direction that would effectively mean the abandonment of the price stability mandate by the Bank of England. A more likely scenario is what might be called a coordination of opposites with fiscal policy responding to the energy crisis with greater spending whilst the Bank of England tightens rates severely. This is not necessarily dysfunctional, but rather an essential division of labour between the fiscal and monetary side. What we would not expect to see from a Truss administration is the kind of thorough-going “discipling of capital”, which Gabor calls for.

In the Eurozone too, though as Gabor has brilliantly shown the logic of the existing institutional set up is coming apart at the seams, does it follow that the resulting tension will resolve itself in any logical way?

Gabor promises us that:

The history of central banking teaches us that policy paradigms die when they cannot offer a useful framework for stabilising macroeconomic conditions, but never at the hands of central bankers themselves.

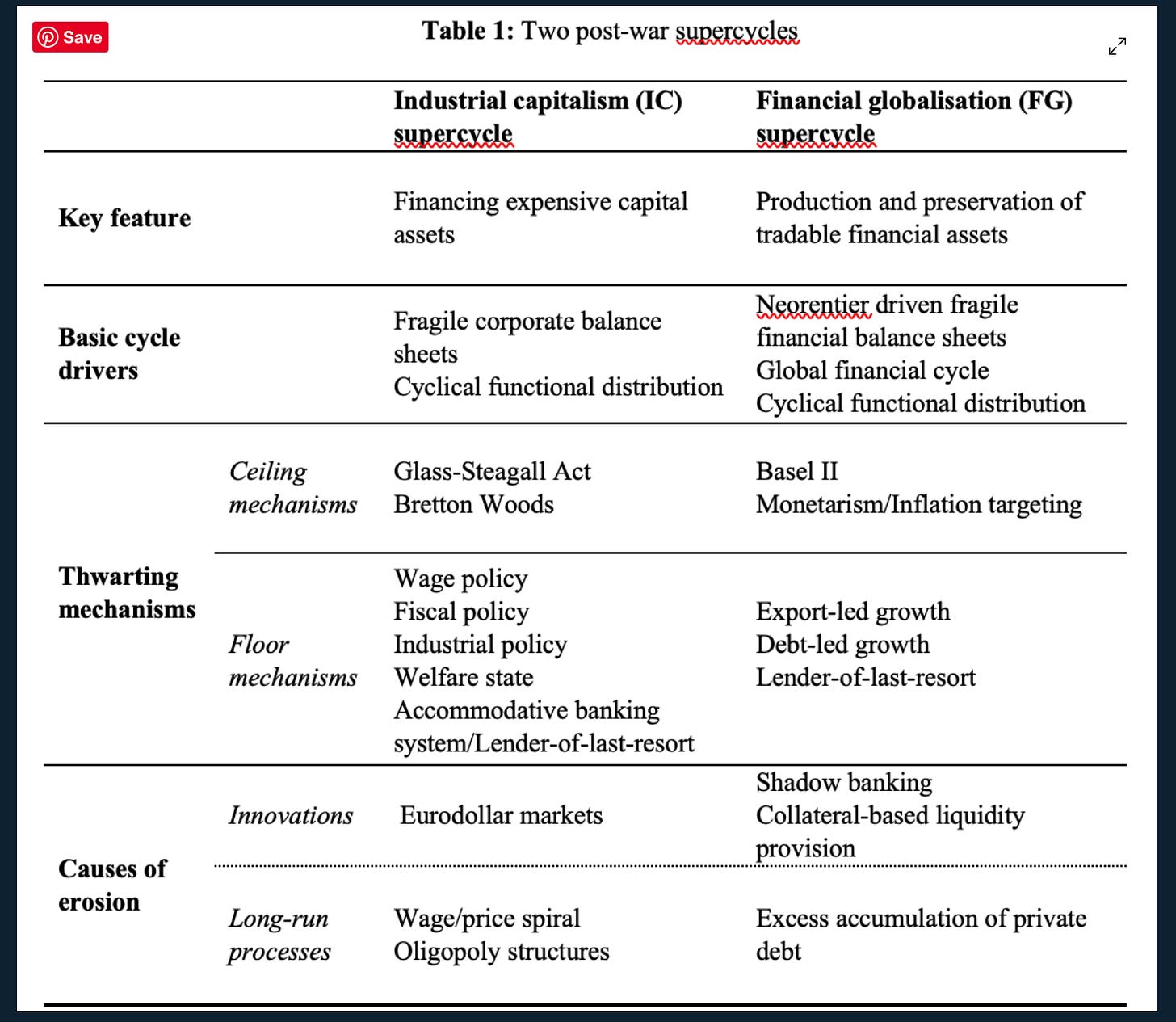

This invocation of history puts me in mind of Gabor’s ambitious collaboration with Yannis Dafermos and Jo Michell on “Institutional Supercycles: An Evolutionary Macro-Finance Approach”. In this work they trace two postwar supercycles in the structure of macrofinancial regulation.

On this basis of this historical narrative they argue that:

Since around 2013 … rich nations have been in the genesis phase of the supercycle: rapid institutional change triggered in the crisis phase of the financial globalisation supercycle

But where will this phase of institutional change lead? Will it lead to a new paradigm? As far as both the dollar system and the eurozone are concerned I am skeptical.

It is comforting perhaps to think of our current moment as an interregnum, a hiatus before a new more coherent structure emerges, whether “at the hands” of central bankers or not. But that implies that beyond the current phase of “transition” lies a new order, a new “regnum”. Why should we assume that?

The chess analogy is compelling as a description of the ECB’s impasse, but depicting history as a game can also be misleading. Outside the game, there is no fixed sequence of moves, nor is there a denouement in the form of a final checkmate.

The vision of an impending paradigm shift in central banking is, I fear, another example of the tendency of fin-fiction to generate out of the diagnosis of tension and dysfunction the promise of a resolution. But are we really facing the “implosion” of a paradigm? Is our reality not something less clear cut? Rather than a collapse or an implosion, is it not more likely that things will continue as they have done since 2008, in an on-going conservative rearguard action, based on a series of makeshifts and half measures?

****

I love sending Chartbook newsletter for free to thousands of readers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options.

There are three subscription models:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

Several times per week, as a thank you, all paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.