In deciphering the global polycrisis it can be helpful to break down the interplay of crisis dynamics into regional systems. The EU and its neighborhood, for instance, is one such region, tied together by political institutions, economics and geopolitics.

Geography matters because regions are tied together by the gravitational pull of trade, through flows of migration, or cross-border cultural and political currents, through the friendships and antagonisms of neighbors, by proximity to particular geographic features – major rivers or canals (in Central America), choke points (like the Horn of Africa) – and by relations to major external powers (Russia, China, USA).

A giant space like Asia can be broken into a series of megaregions:

North East Asia, which is dominated by tensions around and within China.

Central Asia, where the China-Russia axis is key.

South East Asia is more insulated from great power rivalry and is, comparatively speaking, a zone of rapid development. Indonesia, notably, has emerged as a success story of the moment.

In Chartbook #56, I picked out Western Asia, stretching from Lebanon to Afghanistan, as a zone of regional polycrisis. I was delighted to see Esfandyar Batmanghelidj developing this theme in a recent twitter thread.

1. West Asia is in a deep crisis.

— Esfandyar Batmanghelidj (@yarbatman) September 18, 2022

We don't usually think about diverse countries like Russia, Pakistan, and Lebanon as being part of the same region.

But they are all part of West Asia, a region that is at the center of the "polycrisis" @adam_tooze and others have mapped.

In the current moment, the macro-region that is caught up in the flood of polycrisis is South Asia, the region, which as the rather good wikipedia entry puts is, “is delineated by the Himalayas on the north, the Hindu Kush in the west, and the Arakanese in the east”.

In the new world of climate change, mountains, rivers and flows of water matter.

The nation states of South Asia, emerged out of the shattering of larger encompassing imperial frameworks, most recently the British Indian Empire. India, which was once itself a zone of crisis, has emerged thanks to its rapid economic growth since the late 1990s as a new hegemon. Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh remain susceptible to acute existential crisis on account of poverty, demographic pressures and contested political systems combined with acute environmental pressures.

At 1.36 billion people and counting, India will soon be the most populous country on earth. Pakistan with a population of 216 million and Bangladesh with a population of 163 million are number 5 and 8 in the world rankings. In the next decade the region will be home to one quarter of humanity or more.

Pakistan is not formally classified as a Least Developed Country because, like Nigeria, its huge population means that its economy is simply too big. Bangladesh, one of the economic success stories of recent years, now has a higher GDP per capita than India and is on the cusp of formally graduating from the LDC category. The UN has apparently pencilled in the ceremony for 2026.

South Asia is a zone of regional conflicts and global geopolitical struggle. The fact that Afghanistan and Pakistan can be labeled as belonging to West Asia as well as South Asia highlights their pivotal geopolitical role. Rivalry in the region between the USA and Russia/Soviet Union dates back to the Cold War. China looms to the North East.

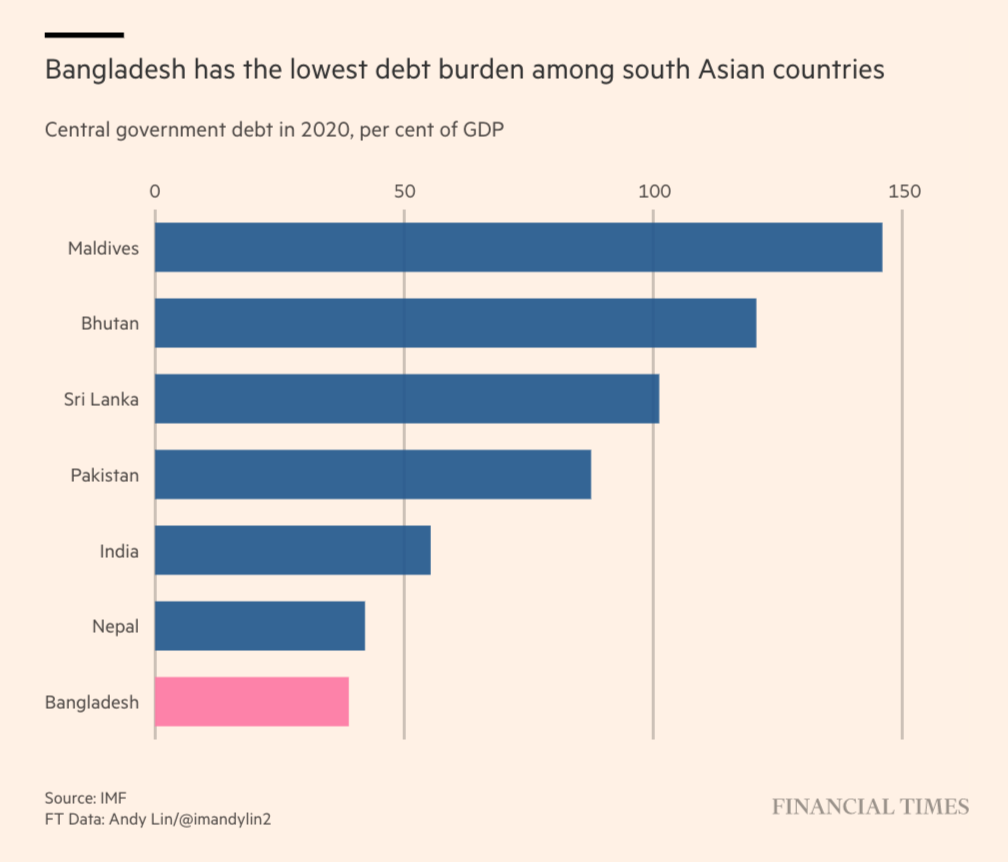

On top of politics and geopolitics, the region is integrated into the world economy through commodity markets and debt. In 2022 debt has been the main driver of crisis. Whereas Bangladesh and India are in a relatively strong financial position, Sri Lanka and Pakistan have debt levels which, for low-income countries, are critically high. Pakistan has neither the export revenue nor tax flow adequate to service such a financial burden.

Both Pakistan and Sri Lanka owe a large share of their debt in foreign currency. Apologists for Pakistan like to point out that whereas Sri Lanka owes a large amount to commercial lenders, almost all Pakistan’s debt is to international financial institutions or other governments.

Large external debts are a chronic source of vulnerability to crisis. The turning point in the global monetary and financial environment at the beginning of 2022 did not bode well for debtors anywhere in the emerging market or low-income world. And the situation of South Asia was compounded by its heavy reliance on energy imports priced in dollars. As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Western sanctions convulsed global oil and gas markets, prices surged and the Fed hiked interest rates, the currencies of energy importing countries devalued, forming a vicious circle. In Sri Lanka a barrel of engine oil that cost 150,000 to 200,000 Sri Lankan rupees ($414 to $552) in 2020, surged to one million SL rupees in 2022. The price of imported paint rose 900 % putting huge pressure not just on transport but construction.

This by itself would have delivered a heavy blow to confidence in the region, but in early April the energy and currency shock was compounded by political crises in the two most fragile states in the region. First Sri Lanka’s ruling clique declared a state of emergency and hunkered down to fight it out. In Pakistan Imran Khan was forced from office by a thirteen party coalition bent on removing him and his Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) government from power. Rather than accepting the outcome and the new government headed by Shehbaz Sharif, the PTI responded by resigning from the national assembly and Khan took to the streets declaring himself to be the victim of an American-backed coup.

Political uncertainty and financial pressures compounded each other. Sri Lanka stumbled towards outright default. Pakistan’s currency plunged and its sovereign debt was downgraded to junk. Hoping to gain the approval of the IMF the new administration in Pakistan saw no option but to pass on global price increases to the population in higher prices. Diesel prices were hiked by nearly 100% and electricity prices almost 50% over a few months. It did not take long for Rickshaw drivers to go the streets.

To aggravate the situation, in the summer of 2022 Pakistan and Northern India were dealing with a historic heatwave. Both countries managed to keep excess deaths to a relatively low level, but it put additional stress on their energy systems as desperate people scrambled for cooling.

Taking together the environmental shocks, the financial pressures, social crisis and political upheaval, commentators began to ask in the early summer of 2022 whether South Asia might be about to experience a 1997-style Asian debt crisis. And those questions became even more pressing over the summer as the full extent of the energy squeeze began to make itself felt. Whereas earlier in the year the problem had been oil and gas prices and the exchange rate, now South Asian countries found themselves simply unable to find sellers willing to supply them.

As Bloomberg reported:

With LNG rates rallying about 1,300% in the last two years, Pakistan and Bangladesh haven’t been able to secure a single spot shipment for months. BSRM Steels Ltd., Bangladesh’s largest steelmaker by market value, cut production by at least 20% due to the nation’s power crisis, according to Aameir Alihussain, a managing director at the company. “Nobody is insulated from this crisis,” he said.

Globally, gas was the pinch point, but in a region like South Asia, oil too can become a major problem. Devaluation, surging prices in local currency and fears about creditworthiness cause supplies to be cut off. By the summer Pakistan found it difficult to buy oil and gasoline and the prices it paid for shipments were exorbitant. In June, costs surged almost 150% year-on-year and contributed to about half of the country’s overall $7.9 billion import bill. As Sri Lanka teetered on the edge of open insurrection, India whose refineries normally supply Sri Lanka, began asking for upfront payment of cargos, intensifying the credit squeeze.

By July the pressure was spreading even to Bangladesh, the model-student in the region. Commentators remarked on the irony that: “Bangladesh, a very internationally oriented economy known for its garment sector, is getting killed by economic conditions elsewhere in the world.” Even India found that its LNGs deliveries were being redirected to Europe which would pay virtually any price to refill its gas stocks ahead of the winter.

To manage the crisis governments looked for makeshift solutions.

The Bangladeshi government started the year boasting of its achievement in providing electricity to 100 percent of the country. But unfortunately, Bangladesh produces 52% of its electricity using natural gas. Since 2018 it had been supplementing declining domestic production of gas with LNG imports and to make matters worse in 2021 it bought 42% of its LNG on the spot market. This exposed it to the historic price shock of 2022. A further point of vulnerability were its fleet of diesel-fired power plants, which contributed roughly a tenth of its power supply. In a humiliating climbdown, the government that had been promising to make Bangladesh into the next Singapore was forced to enter into discussions with business over power rationing. The world’s No. 2 producer of garments introduced rolling holidays to divide up the available power. On top of that the government announced a 52% rise in oil pries and hikes in bus fares. Unsurprisingly, by August it faced street protests.

Pakistan thought it had found a solution to its energy crisis by calling on its Taliban allies in Afghanistan to supply it with cheap coal. With the Afghan economy on the point of collapse and the Taliban in need of all the foreign support they could get, surely they would be cooperative. Islamabad desperately needed the coal for its Chinese-built power plants and for its cement and textiles industries, which normally rely on South African coal for heat and power. By March 2022 Pakistan was facing international coal market prices of $425 per ton, eight times the price it had paid in 2020. If Pakistan could pay its Afghanistan allies not in dollars but in Pakistani rupee, Radio Pakistan announced, it would make a foreign currency saving of $2.2 billion annually. The news did not go down well in Kabul where the Taliban are at pains to distance themselves from their foreign backers. As soon as Islamabad showed interest in Afghan coal, the Taliban announced they were imposing duties and taxes that raised the price from $90 per ton to $200. Mufti Esmatullah Burhan, a spokesperson for Afghanistan’s Ministry of Petroleum and Minerals, told Nikkei Asia.

“The price of coal per ton in the global market is around $350 and the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan will exploit its coal reserves by selling it at international rates, imposing duties on export of coal abroad,”

The regime in Kabul may be isolated and reactionary, but it is not ignorant of the state of the world economy.

With even Afghanistan pulling up the draw-bridge, in July the pressure on the weakest link in the South Asian chain became too much. Sri Lanka’s government was swept away by dramatic popular protests. In Pakistan Imran Khan has relentlessly rallied his supporters to dispute his ouster. In Bangladesh too, street protests were rapidly becoming politicized.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party attacked PM Sheikh Hasina’s government as a “tool to suppress people.” Abdus Salam, convenor of the BNP’s Dhaka Metropolitan South, told reporters, “We assume people who are not directly involved with politics will also join the protests.”

By August, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Pakistan were all in urgent negotiations with international creditors. Bangladesh did so not as an act of desperation but as a precautionary measure to ensure that it did not run into problems. With the trade deficit widening to a record $33.3 billion in the fiscal year ended June, Bangladesh’s fx reserves had fallen to a point where they would cover no more than 3 months imports. Bangladesh quickly entered into negotiations with the IMF, but by the World Bank and Asian Development Bank too. No one wanted to see the model economy of South Asia in trouble.

Sri Lanka, by contrast, was bartering for survival, desperate for any support it could get. By way of bargaining chips, its geopolitical significance is really all it has going for it. Already in 2017 the financial crisis at the port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka triggered Indian alarm over Chinese debt imperialism. This has helped to make India into a key player in the Sri Lankan bail out. Colombo came to terms with the IMF in early September and promptly opened talks with the Chinese.

China is a key creditor of both Sri Lanka and Pakistan. As world economy has been convulsed by shocks in recent years, China has shifted from One Belt One Road development lending to making tens of billions of dollars in emergency loans. According to AidData, a research lab at William and Mary, state-owned Chinese banks made a remarkable 24bn in balance-of-payments loans to Pakistan and Sri Lanka in the past four years the majority of which went to Pakistan.

By July 2022 Pakistan’s situation was by any definition desperate. The rupee was hit by repeated bouts of speculative attack. Foreign exchange reserves, having fallen $7bn since February, were down to $9bn in July, equivalent to only a month and a half of imports. But, with ten times Sri Lanka’s population and its deep connections in the Arab world, the Pakistani elite gamble that they are too big to fail. Pakistan was dealing not only with the IMF but with the Gulf states. Desperate to demonstrate that it can control the situation, with Khan roaring back to popularity in regional polls in Punjab, the new government insisted that it had enough financial cover lined up. As the FT reported. And Pakistan’s central bank governor agreed. He

… rejected market concerns about Islamabad’s worsening liquidity crunch as “overblown … On the external debt servicing side, the next 12 months — while they look challenging — are not as dire as I think some people make them out to be,” Syed said. “Especially as we have the cover of the IMF programme during what is going to be a very difficult 12 months globally … We have external financing needs of about $34bn in the next 12 months and we have financing already identified because of the IMF programme of over $35bn,” he said. “So we are over-financed, actually.” Syed said that he expected the next $1.3bn IMF disbursement from its $7bn facility to be approved in August, though this might be complicated by summer holidays.

Amongst funding sources, Pakistan has received an urgent loan of $2bn from China. And, at least on paper it has a swap line with the People’s Bank of China. Saudi Arabia has renewed a $3bn desposit at Pakistan’s central bank. The 2019 program with the IMF will ultimately provide $7 billion. Pakistani authorities also hope for $3bn from Qatar and $1bn from UAE.

Pakistan is important. Pakistan has powerful and rich friends. Pakistan is not Sri Lanka is the key message. But as international analysts noted, as far as politics are concerned that cuts both ways. In Sri Lanka, the extremity of the situation has left domestic political players with little room for dissent. Pakistan is profoundly divided and barring a break with the constitution, there must be elections by October 2023.

And whilst the focus was on opinion polls, energy prices, debts and elections, what all eyes should have been on in the later summer of 2022, was the rain.

Of course, it rains heavily in monsoon season every year across South Asia. If it does not, it is a disaster. But by early August it should have been obvious that 2022 was different. As the rain came down seven times more heavily than normal, the rivers and reservoirs of Sindh and Balochistan filled and kept on filling and then they began to burst and on August 25th, as the government declared a state of emergency, Pakistan found itself facing a historic catastrophe.

Pakistan has suffered mega floods before. In 2010 a megaflood engulfed one fifth of the country and killed 2000 people causing $10bn in damage. What has happened in 2022 is far worse. In 2010 the rain was excessive for a matter of days. In 2022 it continued at elevated rates for weeks and has been compounded by the melting of mountain glaciers.

By early September a third of Pakistan was under water. 40 million people, one fifth of the population are displaced, a third of the country was under water and more than half of its 160 districts have been declared “calamity hit”. A million houses have been destroyed or damaged. More than 160 bridges had collapsed or are severely damaged and thousands of miles of roads have been damaged. Hundreds of thousands of farm animals have died, and as many as 73,000 women are expected to give birth over the next month without adequate medical support. In some ways it was a miracle that only 1400 people have so far been declared dead.

It should be a world historic moment. At this point, our habit of talking about climate change as a future risk has once and for all, to stop. One third of the fifth most populous country in the world, one of the most sensitive geopolitical hotspots on the planet, is under water. 40 million people are displaced. The climate emergency has arrived. This is not a drill.

It is undeniable, of course, that it is rich countries that are responsible for climate change as they are also responsible for the shock running through energy markets. With good reason, therefore, the flooding in Pakistan, which scientists attribute in considerable extent to global warming, has prompted calls for foreign assistance and reparations. At the very least, it is time to give real urgency to the so-called “loss-and-damage system” which is the mechanism discussed at COP for many years for channeling assistance from rich countries to poor countries living with the effects of climate change.

But as local critics point out, there may be nothing that Pakistan can do about rainfall that is five or eight times heavier than normal, but at the margin local preparations make a difference. As Arifa Noor writes in Dawn, lessons should have been learned from the 2010 floods with regard to canalization of water and location of housing development. David Wallace Wells has an interesting interview with Noor in the NYT.Shehryar Fazli, a political analyst and consultant based in Islamabad, made the same point to the FT: Pakistan had “not spent the time learning from the experience” of the 2010 floods, nor done enough to improve infrastructure and the preparedness of institutions, or to mitigate environmental risks such as inadequate soil resilience that were now disproportionately hitting Pakistan’s poor.”

How much difference this could truly make given the sheer volume of water is an open question. But more preparation is certainly better.

The final tally for the current disaster is anyone’s guess at this point. If the 2010 floods that affected 15-20 million Pakistanis came to $10 billion, it would not seem unreasonable to set the tally this year in region of $!5-20 billion, which would be 4-5 % of GDP. For an economy already reeling under the impact of devaluation, power cuts, and high energy prices and the extreme heat earlier in the summer, which seriously impaired the wheat crop, it is another body-blow. Both rice and cotton crops are likely to be severely affected. Even more urgent are the public health risks in a country a third of which has been underwater. Waterborne diseases — malaria, diarrhea, dengue – and apocalyptic clouds of mosquitos pose an acute risk.

As the FT reports the price of basic food stuffs is sky-rocketing. Efforts to manage the crisis by increasing food imports will further deplete Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves and cause a depreciation of the currency, stoking a dangerous cycle. On the ground in the water-logged countryside, the crisis is likely to trigger greater rural-to-urban migration adding to the poverty and misery of the cities.

How Pakistan’s elite will respond is anyone’s guess. The PTI is excluded from influence at the center. However, it remains in power at the provincial level and is ruling over 75% of the country’s population. As climate scientist Fahad Saeed of Climate Analytics wrote last week “Pakistan is at its nadir of political stability … In a recently called all-parties conference, P.T.I. was not even invited,”. It is “a reflection of the political bitterness, even during the time of worst flooding of country’s history.”

The gamble continues to be that Pakistan is too big to fail. But its economic prospects in the short-run are now grim. The deficit for flood relief is bound to be far larger and the growth rate slower than forecast. For 2023, Pakistan’s government has cut its expected annual growth rate to 2.3 per cent, less than half the previous target. The IMF program agreed only a few weeks ago will need to be renegotiated. Debt reprofiling can no longer be ruled out. As the reality of a gigantic disaster and the inadequate level of financial support has sunk in, the Pakistani rupee has dropped to historic lows.

Across the region, tTe monsoon mega floods of 2022 put a punctuations mark on six months of persistent crisis. Pakistan and Sri Lanka are now both in the emergency ward. Bangladesh too is by no means out of trouble.

Bangladesh has retained full autonomy of action throughout the period of high tension. With a view to enhancing that autonomy, with the encouragement of the IMF, Bangladesh has allowed its currency to float more freely. This will will make its national reserves less vulnerable to speculative attack, but it will add volatility to the price of imported fuel and food. Even in a success story like Bangladesh where the poverty rate halved from 58.8% in 1991 to 24.3 percent in 2016, that should be cause for concern. In 2018 the minimum wage was set at a modest 8,000 taka or $84 and has not been adjusted since. Anyone living on that bare minimum is acutely vulnerable to imported inflation. Further down the line Bangladesh must worry about its corporate sector in a more hostile growth environment and the possibility that its banking system could become mired in bad debts. Of course, compared to the questions facing both Sri Lanka or Pakistan, those are good problems to have.

Throughout the 2022 crisis period, the giant of South Asia, India has remained outside the headlines. It has, experienced the shock to energy prices that the entire world has gone through. India’s import bill for fossil fuels has surged and the rupee has fallen to historic lows. In living memory a shock like this would have rocked India seriously. In 1990-1991 New Delhi ran out of dollars to pay for imports and had to apply to the IMF for a rescue package. At the time India’s per capita income was no more than $390. It did not surpass $400 until 1996. In the decades that followed, India not only recovered, but embarked on a burst of dramatic growth. The GDP per capita figure now stands comfortably north of $2000 per capita.

The jury is still out for what 2022 will mean for India’s role in the region and wider world economy. India went into the COVID crisis of 2020 with an economy that seemed to be floundering. It was hit hard by COVID and the lockdown policy of the central government. In 2021 India’s national COVID emergency meant that it dropped out of the global vaccination program. Meanwhile, in 2021 India experienced an energy crisis that though synchronized with the crises in East Asia and Europe was overwhelmingly homegrown. As an energy importer, the energy price shocks of 2022 have hurt India, but it now has the economic resilience to absorb a heavy hit on its balance of trade. $600 billion in foreign exchange reserves mean India can pay for its imports for 9 months in ready cash.

In the global power game, New Delhi has no doubt relished its role balancing between the Western-led coalition, Russia and China. But a no less urgent question is how it will respond to the regional polycrisis. In the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, China acted as a stabilizing hub and an engine of growth. Can India do something similar for South Asia? Not that India has the same significance as an import market as China does. But assuming that a detente with Pakistan is out of reach, the question is whether it can face eastwards and act as a supportive hegemonic power in relation to Sri Lanka and a cooperative partner for Bangladesh in promoting sustainable growth and crisis management in the region. Both Bangladesh and India have provided financial support to Sri Lanka. But Indian refineries have also been fickle suppliers to Sri Lanka. And India’s steps to secure its food supplies by limiting first wheat and sugar and now rice exports have sent shock waves through the global food economy. The decision to impose a levy on the export of particular types of rice, is motivated by the desire to ensure that prices in the domestic market remain manageable. De facto Indian subsidies to fertilizer and power have been helping to hold down global rice prices. Under current circumstances it is easy to see why New Delhi wants to claw some of that back, but the impact will be felt immediately in its neighbors Nepal and Bangladesh. Vietnam and Thailand may make up the difference, there is even talk of a South-east Asian rice exporters cartel. But as much as the effects ripple out to the world at large, it serves to further enhance the pressure within South Asia, the opposite of what a hegemonic strategy would entail.