The headwinds acting on the Chinese economy right now are formidable, on top of collapsing housing markets and the risks of Xi’s Zero-Covid policy, add one more anthropocenic shock, extreme heat. As far as economic policy is concerned, Beijing is walking a tightrope in a storm.

The heatwave affecting large parts of China is, by most metrics, the worst ever recorded.

China is experiencing the worst heatwave ever recorded in global history.

— Colin McCarthy (@US_Stormwatch) August 23, 2022

The combined intensity, duration, scale, and impact of this heatwave is unlike anything humans have ever recorded.

Over 260 locations have seen their hottest days ever during this 70+ day heatwave. pic.twitter.com/TCKvR37Em3

In Wuhan the Yangtze river is running so dry that local residents are taking walks on the river bed itself.

Wuhan river bank, Yangtze River water receded to the centre

— 自由情意#6376 (@sdcltrc) August 21, 2022

Following Chongqing's Jialing River, Wuhan's famous river banks are also drying up, with the Yangtze River water receding to its centre. Wuhan people say: never seen such a sight‼️ https://t.co/ObXD2L5gnh

It is not just an environmental disaster. It has an immediate impact on the economy.

As Caixin Global reports the six areas suffering the extreme heat and drought — Sichuan, Chongqing, Hubei, Henan, Jiangxi and Anhui — accounted for almost half of China’s rice output in 2021. Global Times reports that the Chinese Minister of Agriculture and Rural Affairs Tang Renjian has called for “all-out battle” against high temperatures and drought to secure autumn harvest.

Sichuan is heavily dependent on hydro power and the low water levels have forced power cuts. That directly affects the production of lithium, polysilicon, aluminium and copper. But, more importantly, it places the entire regional power grid under pressure. Major cities, including Shanghai, are making efforts to economize on power usage. The legendary Bund skyline was not illuminated for two days this week. As the FT reports: “Toyota and Apple supplier Foxconn are among the companies that have suspended plant operations in south-west China as the region is buffeted by hydropower shortages caused by droughts and heatwaves.”

As always, on all things China energy policy Lauri Myllyvirta is a key Western voice to follow. This fantastic thread delves deep into the latest China energy crisis.

This is taking into account that reportedly half of the hydropower capacity has been knocked out by the drought.https://t.co/iSQPIX9cgB

— Lauri Myllyvirta (@laurimyllyvirta) August 23, 2022

The power situation would be even more strained if China’s economy were running at full throttle.

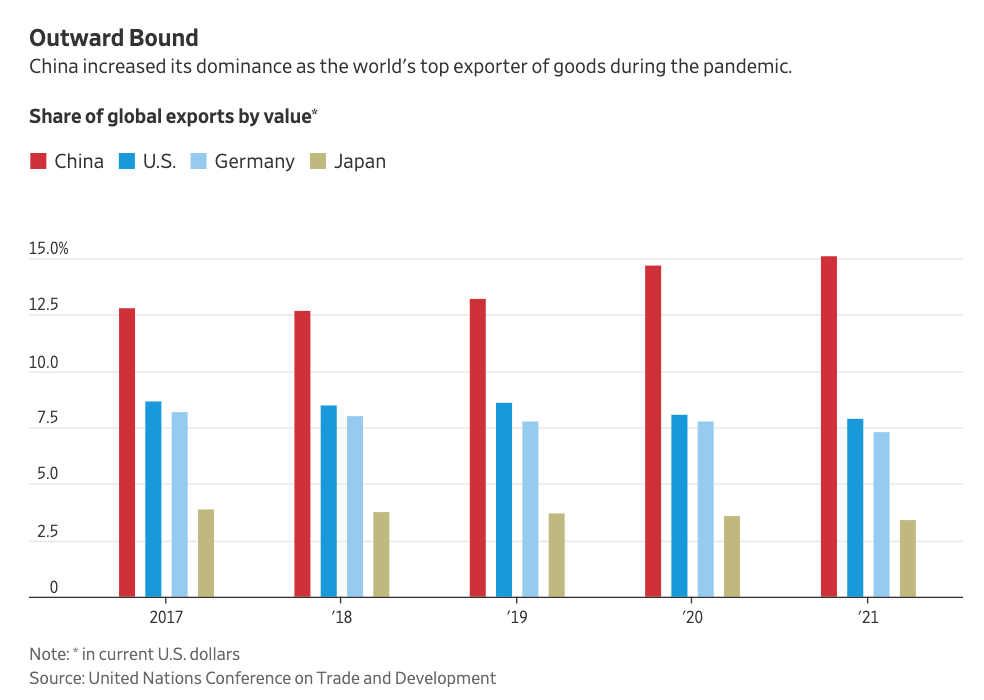

Some bits of the Chinese economy are running hot. In particular, as the WSJ reports China’s exports are booming.

China’s share of global goods exports by value increased over the course of the pandemic, to 15% by the end of 2021 from 13% in 2019, according to data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, which tracks global trade. Major competitors’ share of global exports shrank over the same period, suggesting China’s gains came at the expense of others. Germany’s share of global exports fell to 7.3% in 2021 from 7.8% in 2019; Japan’s share declined to 3.4% from 3.7%; and the U.S.’s share slipped to 7.9% from 8.6%.

But China’s export boom is driven in part by the hunt for markets, which are missing at home. As Paul Krugman argues in a NYT piece, echoing points long made by Michael Pettis and Matt Klein, China’s trade surplus is as much the result of domestic doldrums as overseas success.

The heart of the China’s domestic slowdown is the real estate sector, which since September-October 2021 has been experiencing a slow-motion crisis.

As Matt Klein notes in the FT:

The downturn in the housing market began last summer in response to government restrictions on mortgage borrowing and developer leverage. Homebuilders sold an average of 156mn sq m a month of residential floor space from April to June 2021. This year in the same period, Chinese developers have sold just 106mn sq m a month. The plunge in demand has flowed through to new building, with the amount of “residential floor space started” in April-June 2022 down by nearly half compared to last year. The pace of homebuilding has not been this slow since 2009.

As Michale Pettis outlines in a brilliant blogpost for the Carnegie Endowment, a downturn in property prices risks unraveling the entire housing finance system. In the nightmares of the Chinese leadership the mortgage strikes that swept Henan province in July would be a harbinger of things to come.

The ramifications of the sudden stop in the housing market are being felt across China’s economy. Consumer confidence has fallen off a cliff.

The unemployment rate amongst young Chinese, aged 16-24 hit an alarming 19.9 per cent in July.

Source: SCMP

Hoping to revive the housing market, the Peoples Bank of China has responded by cutting interest rates. And, in recent days, a variety of non-conventional have begun to take shape. The National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (NAFMII), the interbank bond market self-regulatory body under the central bank, is discussing potential credit guarantees with a handpicked group of six developers. Bloomberg reports that to address the delays in project completions that triggered the wave of mortgage strikes, the Housing Ministry is offering 200 billion yuan ($29.3 billion) in special loans to ensure stalled housing projects are delivered as quickly as possible.

But as Bill Bishop at Sinocism remarks:

The fact that the policymakers appear to have been surprised by the mortgage strikes and unfinished building mess may be another sign that they have a weak grasp of the hidden risks in the economy, and especially around real estate. The latest moves – rate cuts and loan support for some developers – do not seem like nearly enough to change sentiment, but I am not sure anything will do that until we get past dynamic zero-Covid.

Short of a U-turn on zero-COVID, which is not likely before the Party Congress in October, the one thing that might conceivably reverse the downswing would be really large-scale stimulus. This would have to focus on reviving both the housing market and boosting infrastructure. As Gavekal points out, infrastructure spending by itself, however lavish, has never been enough to turn the Chinese business-cycle.

Recent statements by outgoing Premier Li Keqiang make clear that some in China’s leadership grasp the seriousness of the situation. It looks worse today than it did in 2020. So far, however, though Beijing has rolled our dozens of policy measures, their scale has been modest.

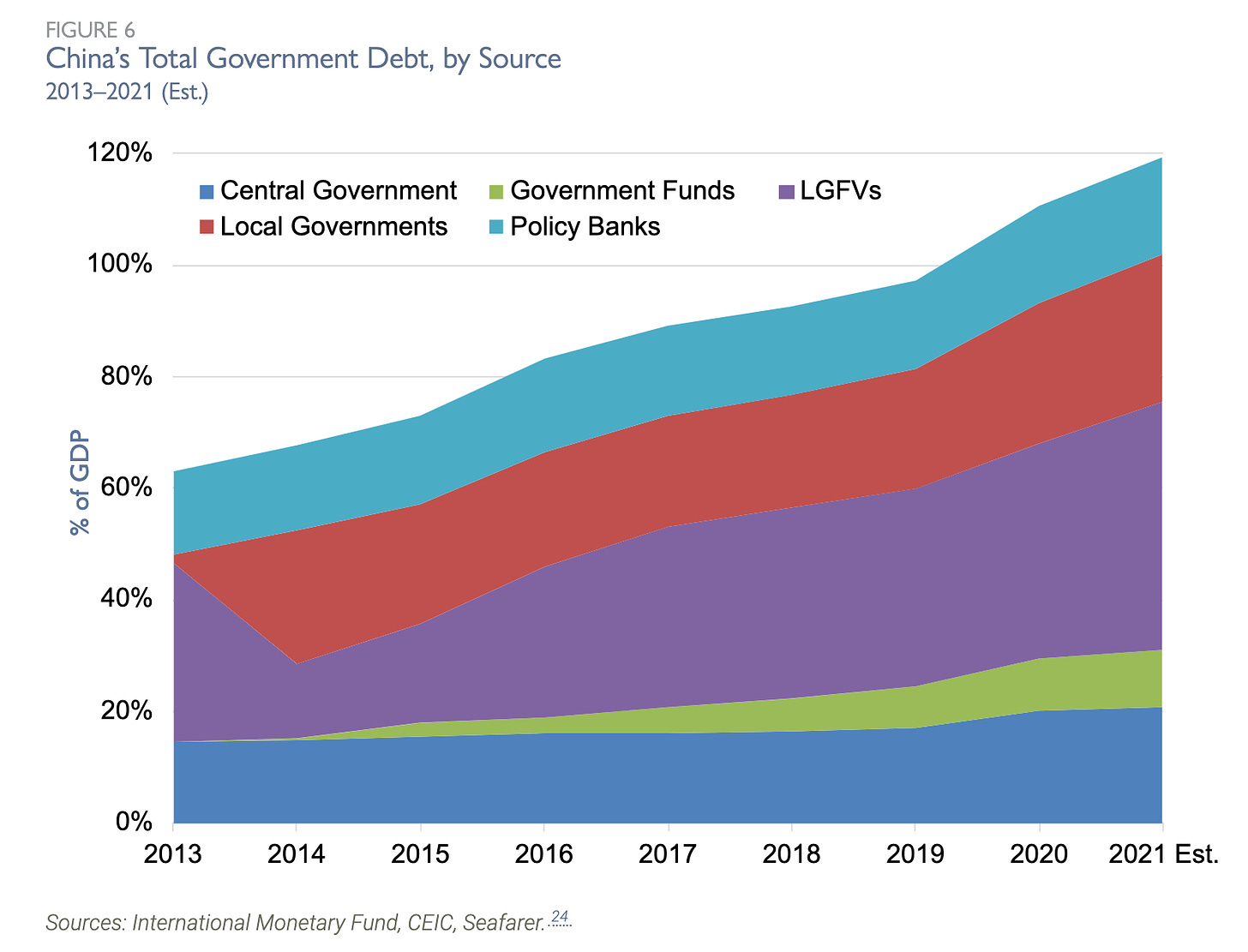

Seafarer Funds, in an insightful analysis, attributes the relatively small scale of the action so far, to the hidden balance sheet constraints on China’s public sector. China’s national debt level may appear modest on paper, but the hidden liabilities of China’s public sector are substantial. Though they continue to receive inflows of funding, local government and local government financing vehicles are financially stretched.

As Seafarer continues:

Recognition that the current system is approaching its breaking point appears to be growing in Beijing, where reforms to the fiscal transfer system that would better balance revenues and expenditures for local governments are under discussion.30 If these reforms involve a net shift in financial resources to local governments, the central government will run a high budget deficit going forward unless it increases taxes. The longer-term solution to China’s current dilemma is getting economic growth back on track. First and foremost, China needs to find the right balance between controlling the pandemic and preserving the economy. Second, it needs to reprioritize economic reform. China’s best path forward is to raise the economic growth rate and grow its way out of debt. Doing so will require a recommitment to economic growth – a goal recently usurped by concerns over national security and control.

Whichever way you look at it, Beijing is walking a tightrope. And the scale of the risks is unprecedented not just for China but also for the wider world. Matt Klein may be right in his recent FT piece to argue that from the point of view of inflation-fighting, the deflationary effect of China’s slowdown is welcome at this current moment. But to take the next step to argue that “China’s troubles may be just what the rest of the world needs”, is surely to push a good point too far. It may be true that “China’s healthy exports and weak imports” were previously a “drag on the global economy, depriving workers elsewhere of the incomes they would have earned selling goods and services to Chinese customers.” But that is a counterfactual argument. A better world is, indeed, imaginable in which China’s current account since the late 1990s was more balanced. Fair enough. Meanwhile, in the actually existing world economy, there are plenty of workers and businesses around the globe who depend heavily on exports to China. None of them will be celebrating bad news from China as good news, especially in light of the pressure also being exercised by a strong dollar and Fed tightening.

****

I love putting out Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.

There are three subscription models:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.