As the combination of the energy price shock and the strong dollar ripple around the world they are putting consumers and governments everywhere under pressure.

In Sri Lanka, acute petrol and diesel shortages helped to bring down the government. But it is not just oil that is tight. In 2022 gas is in even shorter supply relative to demand. And for gas, because of the difficulty of transport, market are much thinner. LNG is the only truly fungible global gas supply and it requires complex and expensive facilities. With Europe and rich East Asian consumers competing for cargos, the price of LNG is spiraling. Poor energy importers like Pakistan are struggling to secure the supplies they need.

As Helen Thompson remarked in the FT:

Across the world, politicians are ever more desperately looking to contain the explosive consequences of the energy crisis. In those parts of Asia, the Middle East and Africa already mired in multiple economic and political difficulties, the crisis is proving catastrophic. Those who import liquid natural gas must now compete with European latecomers to the LNG market seeking an alternative to pipelined Russian gas. … In poor countries, a large proportion of the state’s resources go on subsidising energy consumption. At prevailing prices, some cannot: earlier this month, the Sri Lankan Electricity Board imposed a 264 per cent increase on the country’s poorest energy users. In Europe, governments want to alleviate the dire pressures on households as well as energy-intensive and small businesses, while letting spiralling prices, pleas to consume less and fear about the coming winter drive down demand. Fiscally, this means state funding to reduce rising energy bills by subsidising distributors, as in France, or transferring money to citizens to pay those bills, as in the UK. What is not available anywhere is a quick means for increasing the physical supply of energy.

State funding or transfers presume that there is “fiscal space” to offer this kind of support. In countries already under financial pressure in the aftermath of COVID and now facing rising interest rates, fiscal accommodation is painful.

In her global overview, Thompson mentions Asia, the Middle East and Africa, but Latin America too is feeling the shock. As The Economist remarks

It is not hard to see why governments (in Latin America) are so sensitive to the price of fuel. Latin America is a region of long distances in which roads are paramount in the movement of both goods and people.

As in North America, in South America too, fossil fuel culture runs deep. Indeed, there are parallels in the politics of fossil energy that connect settler-colonial societies around the globe from the Amazon basin to North America, Eurasia and Australia.

Country after country in the region has come under pressure.

In June 2022 after weeks of protests in which three people were killed, Ecuador’s notionally pro-market government was forced to offer subsidies for fuel and fertilizer worth c. 0.8 percent of GDP. In July, fuel price protests brought ordinary life in Panama to a halt and extracted a government promise to cut petrol prices by more than a third.

Since the start of 20222, the governments of Peru, the Dominican Republic, Chile and Colombia have all taken steps to moderate fuel price increases, often under pressure of protests and at considerable cost.

In Brazil – the giant that dominates the continent – Jair Bolsonaro, owed his election in 2018 to the support he gained by breaking ranks with the establishment and backing a disruptive truckers’ strike against the phasing out of fuel subsidies.

And then there is Argentina.

Any mention of Argentina in the context of a global economic crisis is likely to be met with an eye-roll. After Brazil, Argentina with 44 million inhabitants is still South America’s second largest economy. But over the last half century it has racked up an unequalled track record of boom-to-bust and financial crises.

Right now Argentina is again perched on the brink. Inflation is heading towards 90 percent. Protestors throng the streets of Buenos Aires. The government is divided and will struggle to meet the terms of yet another IMF program.

Argentina’s track record is so extreme that it is tempting, in explaining its current difficulties, to point to idiosyncratic national factors. As Simon Kuznets, the legendary growth economist, is said to have remarked, there are “four sorts of countries: developed, underdeveloped, Japan (exceptional for its sustained and rapid growth,AT), and Argentina.”

But, even the most extreme “national case” can never be understood in isolation. Argentina’s history of economic crisis, as particular as it may be, is inextricably intertwined with the history of its region and the world conjuncture. It is the combination of the two – domestic and global forces – that drives its history. It is in this regard an archetypal case of uneven and combined development.

***

One place to start the recent economic history of Argentina would be in the 1970s when Argentina was swept by the tidal waves of the petrodollar lending-boom, before crashing into Paul Volcker’s 1979 interest rate shock.

After stabilizing in the early 1990s by means of a fully convertible currency pegged at one-to-one against the dollar, Argentina became once more a favored destination for foreign investment. And then, by the same logic, it also became the victim of the successive “EM shocks” that rippled around the world – starting in Mexico in 1995, Asia in 1997, Russia in 1998 and Brazil in 1999. By the turn of the millennium Argentina’s position was untenable. The monetary corset that had provided stability in the 1990s had become a noose.

As the dollar rose against all competitor currencies, taking the Argentine currency with it, its real economy was squeezed mercilessly. Argentina desperately needed to devalue, but it could not break the dollar peg without risking a full-blown financial panic. In 2001 a catastrophic crisis ensued. The banking system was shut. Unemployment soared. More than half the Argentine population were pushed below. the poverty line. The currency devalued by two thirds.

The 2001 crisis shocked Argentina politics and society. It revived the fortunes of the left-wing of Peronism, bringing first Nestor Kirchner and then his wife Cristina to power.

For an English-language overview of their period in power I found this survey by Marcela Lopez Levy very handy.

Until they lost power in 2015, the Kirchnerites pursued what might be described as a triple strategy. Economic growth was boosted by the commodity super cycle that made Argentina into a champion exporter of soy beans. At the same time, the left Peronists took a tough but pragmatic approach to negotiations with Argentina’s international creditors, refusing to deal with the vulture funds. That shut off market access, but also had the effect of channeling the money that did flow towards productive investment in FDI. At the same time the Peronists sought to spread the benefits of growth through an expanded welfare state. In this they were not alone. The pink tide that swept Latin America in the early 2000s saw a welcome expansion of welfare, poverty reduction and health care across the continent.

Though frowned upon by many economic experts, Argentina’s strategy had both a degree of consistency and of success. Growth accelerated. Inequality and poverty were reduced. And the formula also saw Argentina through the Global Financial Crisis, perhaps the only global shock to which Argentina has shown a degree of immunity. In November 2008 in Washington DC, at the founding meeting of the G20 leadership meeting, Cristina Fernandez Kirchner (known as CFK) found herself in the unwonted position of lecturing George W. Bush on the perils of unfettered financialized capitalism.

But from 2011 onwards, when CFK won a landslide second term, Argentina’s latest success story began to unravel. The fiscal balance deteriorated sharply. Political rhetoric heated up on both sides. And in 2015 CFK was ousted in a humiliating defeat by the conservative pro-market Mauricio Macri.

Macri promised a classic liberal package of retrenchment and opening up. He delivered privatization and slashing cuts to welfare. Meanwhile, he came to terms with the creditors and opened Argentina up to foreign capital flow, which resulted in a dramatic influx of money and a destabilizing crisis. For this most recent crisis, the article Old Cycles and New Vulnerabilities: Financial Deregulation and the Argentine Crisis by Pablo Gabriel Bortz,Nicole Toftum,Nicolás Hernán Zeolla in Development and Change May 2021 is essential and timely reading.

In May 2018 a sudden loss of financial confidence triggered a dramatic peso devaluation. As inflation surged, real wages plunged, bringing about a recession. And the IMF worsened the situation both by adding new debts to those that Argentina could already not afford to pay and insisting on severe budget cuts – a halving of the deficit from 2.7 to 1.3 percent of GDP between 2018 and 2019 – that helped to depress demand.

The resulting crisis was nowhere near as severe as 2001, but it was one of the most savage switchbacks on record and it forced a default not only on foreign debts but also on Argentina’s domestic peso-denominated obligations, a highly unusual occurrence, which puts Argentina’s status as a monetary sovereign into question.

Against this backdrop, the government of Alberto Fernandez that took office in December 2019 struggled to find a new balance that would reconcile debt service with growth, foreign account sustainability and a viable domestic social bargain. It also has to square a political bargain between different wings of the Personist-Kirchnerite movement, that ranges from the centerists around the President to the populist left-wing headed by CFK.

In 2020, in the midst of the devastating COVID shock, Argentina reached a settlement with private creditors and in March 2022 agreed a deal with the IMF. But almost before the ink was dry, that deal has begun to unravel. The question now is whether Argentina can make it through to the end of 2022 without a further savage devaluation, inflation soaring well above 100 percent and a serious recession.

The permutations of Peronist politics, the repeated defaults, the sheer scale of the action, the dizzying inflation rates and tens of billions in defaulted debts, are all elements of the Argentinian drama. But the inner mechanics of these repeated crises are familiar from other settings. Capital flows are driven by global forces. The ideological currents that Argentina navigates are a blend of its national traditions and international opinion. And there are strong structural similarities in the kind of policy instruments that Argentina, like other states of similar income-level, deploys.

As elsewhere in the middle income world, energy subsidies are at the heart of the argument in Argentina over the balance between socio-political imperatives, fiscal deficits, the foreign account and debt service. For most of the last decade, eliminating energy subsidies would have closed most of the fiscal deficit which has been at the center of so much attention in debt negotiations. But that is easier said than done.

****

In Argentina, energy subsidies were adopted in the aftermath of 2001 as part of the Kirchnerite strategy for mitigating the impact of the crisis on ordinary Argentinians. As the AR$ plunged from parity to 3 Argentine pesos to the dollar, households in the lowest income quintile found themselves devoting 15 % of their stretched budgets to water and sanitation, electricity, natural gas, and bus transportation. In response the Peronist government enforced a set of measures to stabilize energy prices. At the upstream end, well-head prices for oil and natural gas were fixed for all domestic transactions. Natural gas prices for households were fixed and heavy subsidies were provided for the diesel fuel consumed by public transportation.

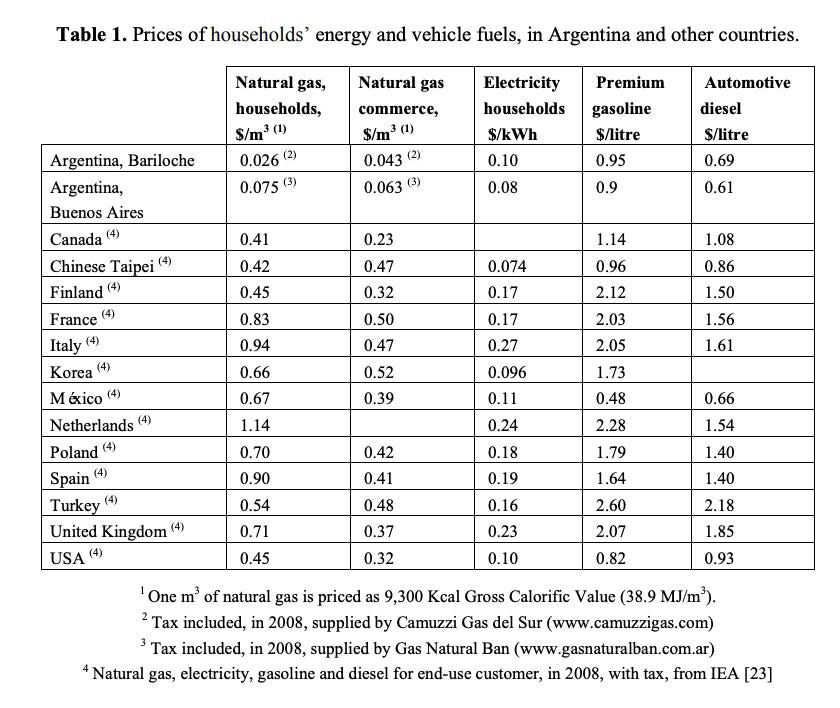

The effect of these subsidies was to uncouple Argentina’s domestic energy price system altogether from world market trends. Argentines enjoyed some of the lowest energy prices in the emerging market or advanced economy world.

Source: Alejandro Gonzalez Energies 2009,

The question of which Argentine’s actually enjoyed these subsidies was a neuralgic issue. The principal vector for delivering subsidies were the controls on the price of natural gas. But a substantial minority of the poorest Argentines do not have access to piped gas and instead rely on LPG, firewood and electricity. They faced considerably higher energy prices. Meanwhile, it was the wealthiest Argentines, in a deeply unequal society, who could make full use of the subsidies.

The energy subsidies became in the felicitous term of Tomás Bril-Mascarenhas & Alison E. Post a “policy trap” – a welfare policy that mutated into a rising and unpredictable burden on the public accounts, supported by deeply entrenched political interests.

h/t Martin Guzman

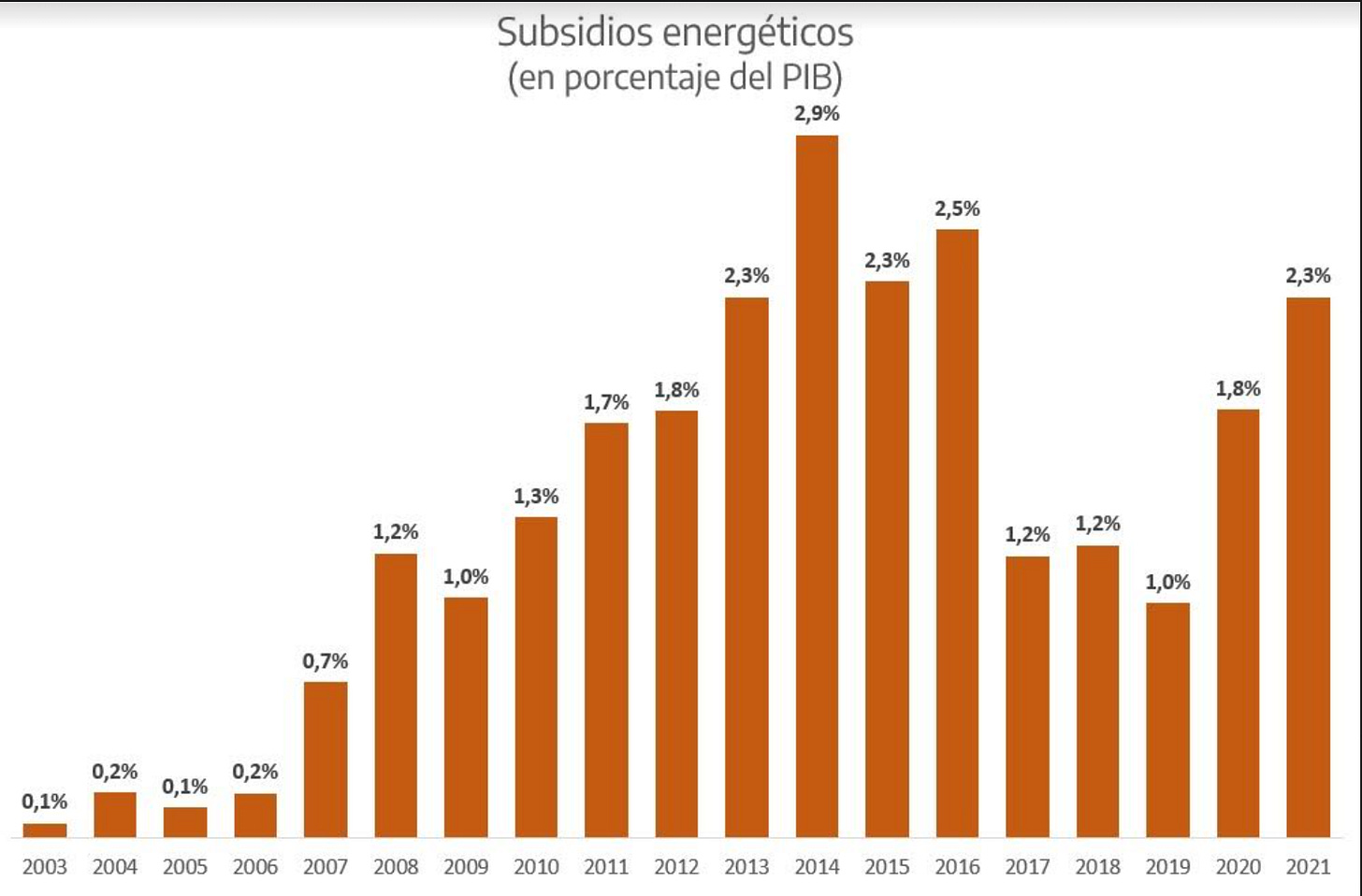

At energy prices surged to a peak in 2014, Argentina’s subsidy regime consumed a remarkable 2.9 percent of GDP. By some estimates the peak subsidy level in 2014 reached 3.5 percent. At that point the subsidy costs were far larger than spending on public investment.

Unsurprisingly, as Macri’s government tried to rebuild relations with foreign creditors and stabilize Argentina’s public finances, these energy subsidies became a primary target. In 2015 Macri created a new energy ministry headed by Juan José Aranguren, the former president of Shell Argentina. He slashed subsidies and allowed prices to rise, a policy attacked a tarifazo. The administration was not blind to the social costs. To offset the pain it introduced a social tariff targeted at less well-off families. But in 2018 the Macri government was overwhelmed by crisis and fiscal consolidation took precedence over all other concerns. Between 2015 and 2019 energy subsidies were slashed by 60 percent, to an estimated 1.1 percent of GDP in 2019.

The IMF and Western interests made no secret of the fact that they wanted to see Macri remain in power. But on the campaign trail, his hardline on utility rates cost him dearly. In 2019 it was the Peronist opposition, with Alberto Fernandez as their leader candidate and CFK in the wings, that made itself into the champion of consumer protection. On the stump Alberto Fernandez pledged to implement a one-year freeze in electricity and gas prices. As analysts warned, with inflation above 50 percent, that measure would have serious implications for Argentina’s efforts to balance its budget. And even though global energy prices plunged in 2020, the subsidy bill duly surged under the new Peronist administration. In the second half of 2021 and early 2022, as energy prices began to rise rapidly, subsidy spending took on increasingly alarming proportions.

In the 12 months to June 2022 the Argentine government spent US$13.5 billion on its energy price support policy, almost twice the spending in the previous 12-month period, according to Julián Rojo, an analyst at the General Mosconi think tank in Buenos Aires. As of May 2022, Argentine consumers paid just 36 percent of the cost of producing power, which accounts for most of the subsidies, down from 42 percent in March. For a country with Argentina’s fiscal deficit and a desperate shortage of foreign exchange, this was completely unsustainable.

Nor is it only gas and electricity prices that are raising the tension. 2022 has seen a surge in demand for diesel as Argentina’s farmers seek to take advantage of the booming commodity prices. The soy harvest is critical to Argentina’s export earnings. But in the Pampas farming regions of the country, diesel was in critically short supply. The most important soy farming region of the world, at a moment of surging global food prices, was running out of fuel This too is an effect of the price control policy.

At government controlled prices, the price for Argentine Medanito oil is set at c. US$65 a barrel. On global markets it fetches closer to US$100. So Argentine drillers export their crude rather than selling it to domestic refiners like state-run YPF SA, which accounts for more than half of the nation’s fuel sales. YFP then has to resort to the spot market spending hundreds of millions of dollars to make up the short fall, thus allowing refineries operate to something close to full capacity.

Clearly the solution is a thorough-going reform of Argentine energy policy to unburden the fiscal budget, ensure a smooth flow of supply, provide adequate funding for future investment, whilst ensuring social protection for the most in need.

A package of that type is what Martin Guzman, the economy Minister in the cabinet of President Alberto Fernandez agreed with the IMF in early 2022. But the package faced opposition from within the government ranks by the left Peronists around CFK who objected to coming to terms with the IMF. In March, her loyalists refused to vote for the measures that their own government had agreed and in the subsequent months it became clear that CFK’s loyalists were blocking Guzman’s efforts to restructure energy subsidies.

The result was a clash that prompted Guzman to tender his resignation on Sunday July 2nd, provoking a crisis of confidence, a plunge in the peso, and a 20 percent step up in prices in a matter of days.

For a few weeks it seemed as though CFK’s wing of the party had triumphed. But as international pressure built on Argentina, threats that global investors would withdraw any funding and after intense talks in Washington, the left-Peronists seemed to have come round to the view that it is better to bite the bullet than to risk a train-wreck. After a brief Kirchnerite interlude, at the end of July Guzman was replaced by a the heavy-hitting Sergio Massa, the number three in the Peronist movement. He has reshuffled the energy team in his Ministry and given notice that he intendeds to implement in outline the energy subsidy reforms that Guzman resigned over.

The extent of the reform will be a test of Massa’s credentials as a Presidential contender. In the mean time Argentina teeters on the brink of a further monetary disaster. One pressing question is whether it can close the gap between the official exchange rate and the market rate, which is more than a 100 percent lower. One consequences of a devaluation would be to drive the price of imported energy up and to force the issue of subsidies. In a sunny August in Buenos Aires, normally one of the coldest months of the year, many are prompted to hope for the best and to count on warm weather. But this begs the question, why is Argentina an energy importer at all?

Argentina has the makings of an energy giant. With steady winds in southern Patagonia and year-round sunshine in the semiarid northwest, it could be a major force in renewable energy. But right now under a center left government notionally committed to a progressive climate agenda, Argentina comes last in the region for clean energy investments per capita. The country spends fifty times more on fossil fuels than on renewable energy development. In 2018, Argentina generated only 2 percent of its electricity from non-conventional renewables, compared to 54 percent in Uruguay, which periodically exports electricity to Argentina and Brazil. Brazil itself derives 65 percent of its electricity comes from hydro and has ambitious plans for non-hydro renewables (half of which is biomass) which may reach 28 percent of the domestic energy mix by 2027.

With YPF, Argentina’s biggest oil company, having been renationalized in 2012, it is clear that the heart of Argentine politics still lies with fossil fuels. But that too, begs the question. Why is Argentina not a fossil fuel giant?

Argentina only became a net energy importer in 2011, as economic growth outstripped lack luster domestic production of oil and gas. But its potential as an energy producer is huge.

According to the US Energy Information Agency, Argentina’s technically recoverable reserves of shale gas are the second largest in the world, after China. The Vaca Muerta formation in the Neuquén Basin, is regarded by many experts as

“best oil and gas shale opportunity outside of the U.S. and Canada,” not only in terms of the quantity of resources, but also their geologic quality.7

The problem is investment, infrastructure and a stable economic environment. According to YPF it would take c. $200 billion to fully exploit the Vaca Muerta and foreign investors will take some convincing to pour that kind of money into Argentina.

A more modest proposition would simply be a pipeline to connect the Vaca Muerta shale zone in Patagonia 400 miles (645 kilometres) to Buenos Aires. That would take care of all Argentina’s energy needs and likely make it into a major exporter.

The price tag for the pipeline project is a relatively modest $ 1 billion – large but hardly unmanageable. Gas could be flowing within 18 months of construction beginning.

Macri’s government, which aspired to restore Argentina’s energy self-sufficiency, first laid out plans for the pipeline, but, faced with low energy prices and a severe financial squeeze, the project stalled. Alberto Fernandez’s government started reviewing the pipeline project from scratch and took two years to draw up its own plans. Energia Argentina then contracted with Tenaris SA, the well-known Argentine producer of seamless steel pipe. But, thanks to in-fighing within the government those tenders are now subject to a judicial investigation following allegations of corruption. Tenaris denies any impropriety. Energia Argentina has put out new tenders.

The upshot is that rather than profiting from an export boom, Argentinians will likely faced gas shortages, cutoffs and a huge dollar outflow to pay for imports.

“Instead of seizing the moment – this global demand opportunity amid the misfortune of the Russia-Ukraine war – Argentina is suffering it,” said Nicolás Gadano, an Argentine consultant and university professor who specialises in the intersection of economics and energy.

It is out of conjunctures like this, missed opportunities over-determined by domestic and international history that national stories of failure are made.

****

I love putting out Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.

There are three subscription models:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.