It is six months since Russia launched its attack on Ukraine.

Amongst the anniversary coverage two long reads by the Washington Post are in a league of their own. One, by Shane Harris, Karen deYoung, Isabelle Khurshudvan, Ashley Parker and Liz Slycovers, covers the build-up to war. The other by Paul Sonne, Isabelle Khurshudvan, Sehiy Morgunov and Kostiantyn Khudov reconstructs the battle for Kyiv. Both are highly recommended.

On the six-month anniversary, the celebrations of Ukraine’s national day serves as a counterpoint to the increasingly sober reporting of the war and uncertainty about the longer-term outlook.

For much of the summer the talk was of an imminent Ukrainian counterattack, which was expected to be launched in the South around Kherson. The hope was that this might break the stalemate and perhaps create conditions under which a ceasefire could be negotiated on terms favorable to Kyiv. By early August it was clear that a large-scale counteroffensive by the Ukrainian military was, in fact, unlikely. Acute observers like Shashank Joshi, Defense Editor of The Economist noted a significant slippage in messaging by both Kyiv and its backers in the West.

Indeed, there was anxiety in some circles that the drumbeat of expectation was putting unreasonable pressure on Kyiv to launch an attack prematurely. This thread by C.M. Dougherty is excellent on this score.

3/22 This pressure may be pushing UKR may to launch an offensive, despite lacking the military means to do so effectively, as laid out brilliantly by @KofmanMichael & @EvansRyan202 in this @WarOnTheRocks podcast: https://t.co/GnMvdl7hNx

— Christopher M. Dougherty (@C_M_Dougherty) August 9, 2022

On the ground there are few illusions about the balance of forces. As the FT quoted Andriy Zagorodnyuk, a former defence minister of Ukraine.

“The US gives us enough to stop the Russians from advancing, to reverse some gains, to shape the operational direction, but absolutely, clearly, not enough for a major counteroffensive,”

This is a far cry from gung-ho talk earlier in the year about driving Russia back to the border. On Washington the turning point may have come in early July, as captured by a piece by Peter Baker and David Sanger in the NYT which flagged up growing unease in the Biden administration about the strategic rationale for US aid for Ukraine (h/t Ted Fertik). Baker and Sanger offered a startling insight into the complex, not to say confused, messaging from Washington:

Some officials, including Mr. Biden, cringed when Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III said in April that “we want to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.” The president called Mr. Austin to remonstrate him for the comment, then directed his staff to leak the fact that he had done so. But officials acknowledged that was indeed the long-term strategy, even if Mr. Biden did not want to publicly provoke Mr. Putin into escalation.

On the basis of such muddled communication what, frankly, are either Kyiv or Moscow to think? Does Washington want to wear down Russian power or does it not?

What is more clear cut are the force ratios on the ground. Fro an offensive against prepared defensive positions, the attackers needs to have an advantages of 3:1 to have much prospect of success. If accumulating such an advantage was ever plausible for Ukraine in the Kherson sector, by mid-August that opportunity had slipped away. As Shashank Joshi, reported

Konrad Muzyka of Rochan Consulting, a firm which tracks the war, thinks there were 13 Russian battalion tactical groups (btgs) in the province in late July (a btg usually has several hundred troops). Now there may be 25 to 30. “We believe that this window of opportunity has passed,” says Mr Muzyka. “Ukrainians do not possess enough manpower to match Russian numbers.”

As Joshi found to his cost, this was not a popular view. The comments on this twitter feed make for enlightening reading.

My piece on the “counter-offensive”: Ukraine is squeezing Kherson city, but its army may not be ready for a big offensive. Ukraine’s political imperatives—the need to demonstrate progress to Western backers—might be in tension with military considerations. https://t.co/JEYm8rUSVE

— Shashank Joshi (@shashj) August 14, 2022

But as other sources, such as The Guardian, reported, Joshi’s downbeat view is, in fact, widely held.

Ukrainian commanders … concede that a big push in Kherson is some way off. “We have more weapons. Not enough to do an offensive now and to beat the enemy. It is enough to defend our territory,” said Roman Kostenko, a pro-European deputy who heads the parliamentary defence and security committee.

Often the debate about Western support to Ukraine is concretized in the form of weapons systems. First there were the Javelins. Then there were the Himars rocket launchers. Now the talk is of ATACMS.

Ukraine’s Himars rockets have a range of about 50 miles (80km). … So far the Biden administration is refusing to supply Kyiv with Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) rockets, which can be used in Himars systems and have a 185-mile range. Its reasoning is that Ukraine could use them to strike Russia itself, an act the US fears may lead to a third world war. Zelenskiy dismisses this scenario and has pledged not to attack Russian territory. Negotiations continue, as the Pentagon reviews the situation.

The focus on equipment makes for good headlines, but it deflects from the broader operational and strategic picture and the longer-term question of how the war can be continued and for what purpose.

Dara Massicot in Foreign Affairs defines the objective in more limited terms. The aim is not so much a decisive breakthrough, as to foil Russian efforts to annex Ukrainian territory and to drain their military power, eventually forcing Putin to give up. To achieve this more limited goal, what may suffice is simply attrition.

If Ukraine can create a highly contested frontline—just as it did outside Kyiv and Kharkiv—with attacks on command-and-control points, high rates of equipment losses, and large Russian casualties, it may again convince Moscow to withdraw. But for such a Ukrainian strategy to have the best chance of success, it must be in progress before Russia attempts to annex the territory it holds; that way, Ukrainian attacks can deny Russia a foothold in an area like Kherson. And even if Russia does annex Ukrainian territory and tries to force an operational pause, Kyiv and its Western supporters don’t have to comply.

On the question of a “highly contested frontline” and the attrition of Russian strength, one of the fixed points in Western analysis of the war, is the evidence that the Russians are suffering much higher casualties than the Ukrainian side. But how accurate are our casualty figures and how are they estimated?

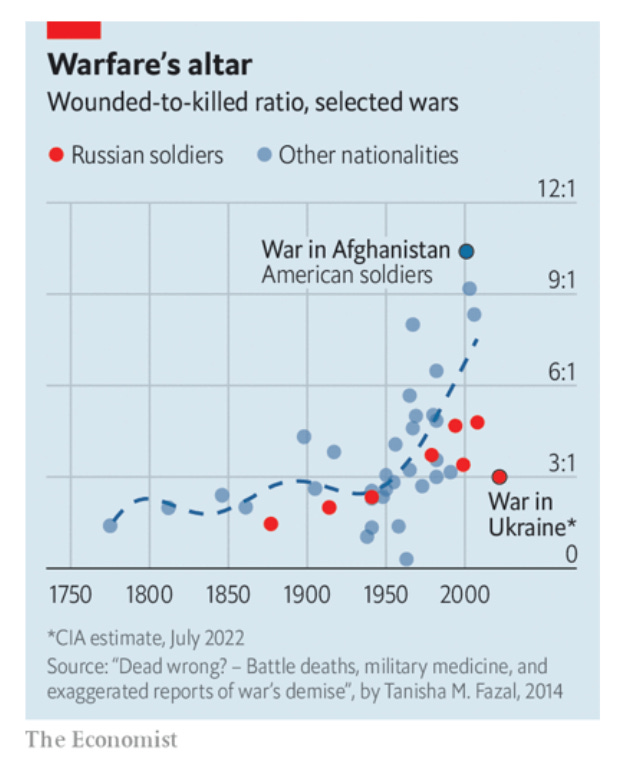

On this grim subject The Economist provides excellent analysis. It turns out that estimates of Russian casualties depend on a macabre parameter known as the “wounded-to-killed ratio”. This is a ratio that reflects the intensity of fighting, the sort of weapons used (shrapnel v. machine-guns) and the availability of rapid battlefield medical care. In the 20th-century a ratio of 3 or 4:1 was normal. But in recent conflicts thanks to rapid medevac the United States has been able to push the ratio as high as 10:1 – of eleven of its soldiers who are hit by enemy fire, one dies and 10 survive their wounds. Ironically, in the case of the Russo-Ukraine conflict, since we know the number of killed Russians with relative accuracy, a higher “wounded-to-killed ratio” would be bad news for Moscow, since it would imply a greater number of overall casualties. The consensus seems to be that the ratio probably hovers at an unremarkable 3.5:1, which implies an estimate of Russian casualties in the order of 70,000 killed and wounded.

If the West is increasingly counting on attrition, that shifting outlook has not been lost on the Russians. An interesting view from the other side is provided by a piece in Kommersant by Russian think tank director Andrey Kortunov. As he remarks:

… Western historians today recall the “miracle on the Vistula” a century ago, when in the summer of 1920 the Polish state managed to stop the Red Army’s advance on Warsaw and push it far to the east. A hundred years later, in the United States and Europe, they started talking about the coming “miracle on the Dnieper”. It seems that one more effort, one more strain, one more week or a month – and the Russian military machine will start to falter, rolling back to Donetsk and Lugansk, and even to Rostov and Belgorod. But week after week, month after month passes, and the dates of the expected “miracle on the Dnieper” are shifting further into the future, like an elusive horizon line. The growing supply of Western weapons strengthens the Ukrainian army, but still is not able to change the overall picture of what is happening. Russian forces, albeit cautiously and without spectacular breakthroughs, continue their stubborn advance in a westerly direction. The situation on the battlefield, albeit slowly, is changing in favor of Moscow, which, in turn, is tightening Russian conditions for future political agreements. Is the West able to reverse this trend? Such an all-in game would involve a sharp increase in the scale of military support for Kyiv. But in this case, it is likely that NATO would be directly involved in the Ukrainian conflict, after which the twenty-year Afghan saga would most likely seem like a cakewalk. It is clear that any decision on a truce, and even more so on a peaceful settlement, should be made in Kyiv. However, a lot depends on the position of the West. If “Plan A”, that is, the victory of Ukraine, looks less and less realistic, then the West should, apparently, already now think about a “Plan B”, which involves achieving at least a temporary compromise not only between Moscow and Kyiv, but also between Russia and the West.

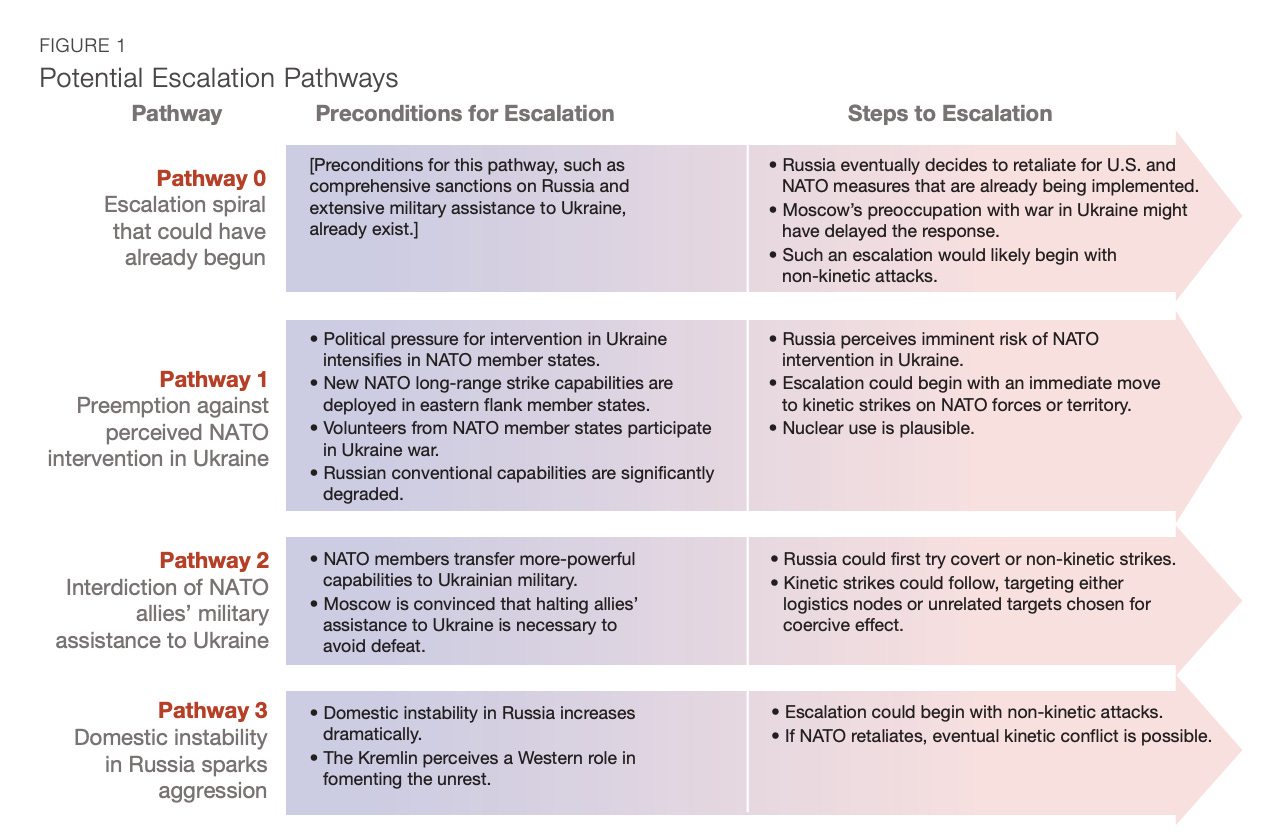

What hangs over the entire discussion, on both sides, is the risk of escalation. In February and March, as the war began, as the West surged its support for Ukraine and ramped up its sanctions against Russia, as Putin responded with nuclear saber-rattling, talk of escalation was everywhere. Since then, fears have calmed somewhat. For a cool-headed assessment of the risk of escalation as of July 2022, a report by a RAND team is worth reading. The punchline is this:

although escalation risks stemming from the Ukraine war are real and significant, the preceding analysis helps to bound those concerns: A Russia-NATO war is far from an inevitable outcome of the current conflict. U.S. and allied policymakers should be concerned with specific pathways and potential triggers, but they need not operate under the assumption that every action will entail acute escalation risks.

The great hope of Western governments was that Western economic sanctions would have a material effect on Russia’s ability and willingness to sustain the war against Ukraine. Battlefield attrition and economic attrition would combine to force Moscow to sue for peace. This, of course, depends on actually making a serious dent on the Russian economy. Six months into the conflict, how far that has been achieved is hotly contested.

As Nick Mulder pointed out in his very timely history of The Economic Weapon, already during the Allied blockade of the central powers in World War I, sanctions were the incubators of economic expertise. And that has been true with regard to Russia in 2022 as well. A lot of people have learned a lot, very fast about Russia’s economy. But, as was true in previous episodes of economic warfare, this collective learning process has not let to consensus.

Over the last month starkly contrasting analyses have been offered on the state of the Russian economy and its likely future development.

At Yale a group pulled together by Jeffrey Sonnenfeld of the Yale SOM have published a sprawling analysis of an impending economic catastrophe in Russia. Their conclusion is that Russia faces not just a long-term deterioration of its position as a commodity exporter, but the prospect of immediate disaster. Their conclusion is that:

Looking ahead, there is no path out of economic oblivion for Russia as long as the allied countries remain unified in maintaining and increasing sanctions pressure against Russia.

The Sonnenfeld report, has elicited numerous replies. Ben Aris has provided one detailed response. Another has come from Elina Ribakova, at the IIF – the think tank and lobby of the international financial industry – who has published in-depth analysis, which is far more skeptical of the weakening of the Russian economy and the extent of the pullback by Western firms.

1/ Sanctions on Russia are proving to be porous not only in energy. While self-sanctioning has been an important contributor to sanctions impact, many companies are still sitting it out. @SelfSanctions @JeffSonnenfeld pic.twitter.com/X3SeroBXgw

— Elina Ribakova 🇺🇦 (@elinaribakova) August 18, 2022

At the macroeconomic level, opinions are similarly divided. Forensic analysis of trade data by Matt Klein at the Overshoot newsletter suggests that Russia is suffering a ruinous squeeze on its imports. But a broader assessment of the Russian situation, again by Elina Ribakova, or by The Economist magazine suggests that the Russian economy is, in fact, in stronger shape than many imagine. Amongst other indictors, imports to Russia, as captured in the export data of its major trading partners, may be down on their prewar peak, but are currently recovering to their pre-COVID level.

Of course, no one disputes that the war and sanctions will be terrible for Russian growth in the long term. The loss of investment and human capital and reputation is irreparable. But, any prospect of an imminent squeeze serious enough to force a change in policy in Moscow seems remote.

The same cannot be said for Ukraine. By contrast with the serious disagreement about Russia’s economic position, there is little doubt that Ukraine is living on borrowed time. To put it simply, Ukraine cannot afford the war it is fighting. The aid it is receiving, though substantial, is an order of magnitude smaller than Russia’s fossil fuel earnings and is entirely inadequate to cover the running costs of the war. As a result, Kyiv is resorting to financing the war by printing money. It can only be a matter of months before Kyiv faces crippling choices between continuing to fight the war and upholding any semblance of normal economic life on the home front.

As Maria Repko deputy executive director of the Centre for Economic Strategy in Ukraine described the situation in the pages of Foreign Policy magazine.

Scarce foreign funding is forcing the National Bank of Ukraine to buy government bonds (effectively printing hryvnia) to cover the enormous budget deficit, which reached $4 billion in May and almost $6 billion in June. In March to May 2022, the government’s own revenues covered just about 40 percent of the expenditures needed to run the country and pay the bills. Another 40 percent was covered by the National Bank of Ukraine. The rest is funded by grants (about 7 percent of expenditures during three months of the full-scale war), foreign loans, and local bond issues. … on July 20 Ukraine asked Eurobond holders for a standstill, because the commercial debt servicing becomes too much of a burden for the budget, as well as from the balance of payments prospective.

That standstill was granted by the bondholders. It buys Kyiv $5.9 billion in relief over the next two years. But that only covers a small part of the financial shortfall. In the mean time,

The National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) was selling up to $1 billion per week to keep up with the pace of foreign currency demand and to defend the exchange rate peg. On July 20, the decision was made to shift the peg upwards, to 36.60 hryvnias to a dollar from 29.25 hryvnias to a dollar. Ukraine’s foreign currency reserves stood at $23 billion as of the end of June. The current pace of losses means that Ukraine will be shortly on the verge of financial collapse if aid inflows are not sped up.

Ukraine’s situation is made worse by the disruption of its economy due to the war, the dislocation of its foreign trade by the Black Sea blockade and by the economic activity of its citizens who are now refugees spread out across Europe. Of the 5 million Ukrainian refugees many are working remotely. All of them are spending money from their Ukrainian bank accounts. The result is a monthly drain of c. $1.5 billion at the expense of Ukraine’s foreign exchange reserves.

The basic point, as Oleg Churiy former deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine spelled out in the pages of the FT, is that Ukraine must come to terms with the long war it now faces not just in military terms, but in economic policy as well.

A longer duration of the conflict alters not only the military strategy but the macroeconomic calculus. In the war’s early days, Ukraine’s macroeconomic policies aimed to control expectations and avoid panics. These policies were based on controlling prices — for example, the hryvnia-dollar exchange rate was fixed at the prewar level — and providing stop-gap measures to support businesses and households, such as suspending import duties. These responses were appropriate to address the initial shock. But as the war grinds on, they need to be adjusted or Ukraine will run into an economic catastrophe.

As Churiy sees it there is no alternative to putting Ukraine’s domestic finances on a sounder footing. That means raising taxes and slashing all “non-essential” spending. But that is hard to do in wartime and is already producing conflict between the central bank, for which Churiy speaks, and the politicians who run the government. As the WSJ pointed out in its portrait of Ukraine’s finance minister Sergii Marchenko there is a simmering dispute between the bankers and the government over stabilization. Marchenko, of course, recognizes that this has become a war of attrition, but his priorities are clear.

“Sometimes we have a different point of view from the National Bank,” said Mr. Marchenko. “We have to worry about winning the war. It is better to risk high inflation than not to pay soldiers’ salaries.”

In a country at war, the implication that the central bank has other priorities than national defense, is dramatic indeed. An independent central bank is ill suited to the needs of total war…

The only way to relieve this conflict is to look for more support from outside. So far, Ukraine has received external support to the amount of c. $2.5bn-$3bn a month. For the second half of 2022 it is expecting $18bn all told. But it needs more. It needs $4bn-$5bn per month immediately.

A lot has been pledge. But frustratingly little has so far been disbursed. Most flagrant of all is the EU, which has pledged €9 billion but delivered only €1 billion on account of internal disputes about the modality of funding. As the WSJ reports:

Germany, which sent Ukraine a separate bilateral grant of €1 billion in June, objected to the commission’s plan to offer low-interest loans backed by guarantees from EU member states (Germany favors grants). Discussion about whether to offer grants or loans, and how to share the burden, has dragged on all summer.

With a new proposal being tabled in early August. As Politco reports: “While there’s no timeline yet, the Commission is aiming to obtain approval by the European Parliament and EU countries in September so that disbursement can start in October, one official said. “

Zelensky’s reponse was merciless: “Every day and in various ways, I remind some leaders of the European Union that Ukrainian pensioners, our displaced persons, our teachers and other people who depend on budget payments cannot be held hostage to their indecision or bureaucracy. Such an artificial delay of macro-financial assistance to our state is either a crime or a mistake, and it is difficult to say which is worse in such conditions of a full-scale war”.

As Zelensky knows, the stakes could not be higher. If, at the six-month mark, Ukraine now faces a long war, then stability is crucial. And that stability must be secured, not just on the frontlines, but on the home front as well, which is “highly contested too”. Otherwise, when Kyiv comes to mark the 12-month anniversary and the 18th-month anniversaries in 2023, the narrative may be less up beat than it is today.