Channelling Rayner Banham for 2022

Ukraine’s successful defense against Russian attack has become a dynamic (re)generator of ideology.

The war has reopened debates about just war and the future of alliances like NATO. I have addressed those themes in two pieces in New Statesman – on Habermas and on NATO. But we need to go deeper.

But it is not just the war in general and the Russian threat as such that are doing the work. Even the way in which the war is being fought has become an ideological generator, a source of inspiration for “the West”.

I want to explore this in two parts.

One is the ideology of the Javelin, which links together a specific type of technology, a mode of war-fighting and “Western” ideological claims. That will be the subject of this newsletter.

A follow up will address the way in which ideological tropes like freedom and initiative are harnessed together in accounts of military tactics and operations, allowing comparisons of the Ukrainian and Russian modes of war-fighting to be nested within cultural dichotomies of East and West.

****

In a previous newsletter I dug into the political economy that produces the Javelin anti-tank missile.

But what kind of vision of war does this anti-tank guided missile serve? In the narratives currently circulating in the West, the Javelin exemplifies a particular ideological understanding of the war.

At one level the clash between Ukrainian infantry and Russian tanks can be situated on one of the most classic divisions on the battlefield – the division between the individual, unarmored fighter and the armored antagonist. To survey this terrain and precisely locate our current moment requires a brief detour into military history.

On the battlefield until the 19th century, infantry used archery or musket fire to keep the cavalry at a distance and compact square formations of spears, pikes or bayonets to withstand the fearsome cavalry charge.

In the second half of the 19th century, the firepower of rifles, steel cannon and exploding shells made both cavalry and close infantry formations dangerously obsolete.

By World War I the infantry dug themselves in, leaving a battlefield shaped by barbed wired and swept by machine gun and artillery fire. To master this new terrain the infantry adopted new, small group, dispersed tactics and to break the deeply defended trench lines World War I gave birth to a new monster – the tank. The tank’s combination of heavy fire power, armor and mobility was radically new.

As with armored cavalry the question was, how to stop the tank?

One could counter tanks with tanks. But that requires an investment in tanks, which is very expensive. And not only that. It requires you to equip tanks with the kind of cannons that are suitable to penetrating the armor of other tanks. Those cannons are not necessarily well-suited for attacking entrenched infantry, the original intention of the tank. Once tanks primarily fight tanks, a truly new, non-infantristic mode of war is emerging.

Other than a tank, the obvious way to counter enemy armor was to fire on the tanks with artillery. This was not easy. Fast-moving targets are hard for big cumbersome guns to engage, especially at any kind of distance. But, for lack of alternatives, field guns and howitzers were pressed into service. Far more suitable, it turned out, were the the fast-firing, rapidly maneuvered, long-barreled guns developed in the hope of shooting down aircraft.

Another important form of anti-tank warfare developed especially during the later phases of WWII was aerial attack. I have said more about this elsewhere.

But to frame the Javelin we need to remain on the ground.

Apart from tank-on-tank fighting and duels between tanks and anti-tank guns, tanks are also vulnerable to another form of attack. Locked down beneath their hatches, lumbering around on their tracks, blind to approaches from many sides, tanks are both intimidating to those facing them and extremely vulnerable to fast-moving, improvised attack by light infantry forces.

In this mode of combat the confrontation of David and Goliath, infantry v. horseman takes on modern form.

One option was to give infantry upgraded rifles that fired armor penetrating shells. Those rifles were potent but also heavy and expensive. Another option was to hurl grenades or Molotov cocktails or, for the very bravest, to slap magnetic anti-tank mines directly onto the hull of the enemy tank. That required almost suicidal courage.

To give the infantry a better chance, the later stages of World War II saw the development of a new and distinctive kind of weapon, the rocket propelled grenade or hollow charge, which defines anti-tank weapons down to the present day.

The advantage of the rocket was that it could be fired from a distance, but it did not need a highly engineered barrel and firing mechanism. The weapon was so cheap it was disposable. It was also recoilless, so it could be fired from the shoulder. That also meant, however, that the rocket was slow – compared to the muzzle velocity of a bullet or shell. Hand held, anti-tank rockets cannot smash their way through armor with kinetic energy. They generated their devastating punch through so-called shaped or hollow charges. These warheads direct their explosive energy into a jet of heat that melts its way through the enemy armor and wreaks havoc in the enclosed space of the vehicle.

The combination of rocket-propulsion and hollow charge produced the German Panzerfaust of the final stages of World War II. A weapon of last-ditch struggle in 1944 and 1945.

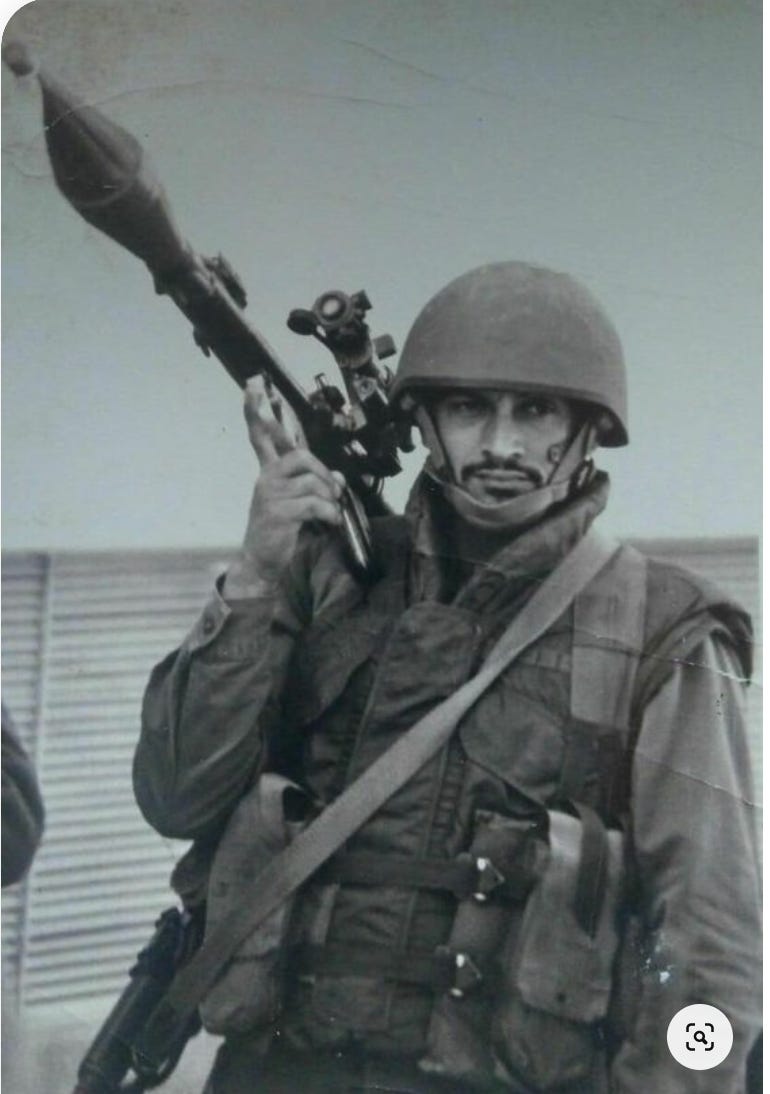

It also gave us the Soviet-era RPG7 that can be seen in use by regular and irregular infantry around the world.

The range of these rocket propelled grenades is not long – 500 m for the RPG-7. They are best suited for urban combat, which enables the infantry to approach armored vehicles using cover. Given the courage required to conduct this kind of combat it is unsurprising that many militaries issue special decorations for soldiers brave enough to kill tanks this way.

In evolutionary terms, close quarter combat between infantry armed with RPG and tanks in an urban setting takes you back almost to a prehistoric scene, in which packs of resourceful early humans hunt big game with crude neolithic weapons. Raw cunning and a rock or a spear hurled at the right moment takes down the Elk or the Mammoth.

This is not the model for the Javelin missiles in Ukraine today. The Javelin is a high-tech weapon that kills at ranges often exceeding those of the Russian tank guns. It is the product of breakthroughs in the postwar period that saw hollow charge warheads combined with more powerful rocket propulsion. The more powerful rockets allowed engagement at longer distance, but also raised problems of accuracy. Unlike a shell fired out of a cannon that – due to its extreme velocity, simple aerodynamics and the direction provided by the barrel – follows a predictable path, a rocket is too unsteady to guarantee a hit at long range. A long-range rocket requires guidance, through fins activated either by wire, or as in the case of the Javelin by infrared and a highly sophisticated internal guidance system.

It was the combination of long-range rocket propulsion with guidance and shaped charge that created the modernAnti-tank Guided Missile (ATGM) – a weapon that combined the lightness and mobility of a personal anti-tank device – Panzerfaust, RPG – with the long-range striking power of an anti-tank gun.

The Israelis first encountered wire-guided Soviet missiles – Saggers – in 1973 in the hands of the Egyptian army and suffered devastating losses on the Suez canal. After decades in which the Israeli tankers had outgunned their Arab counterparts this was a sensation. From the 1970s onwards, military experts have never stopped discussing does the ATGM spell the end of the tank? Might infantry have regained the upper hand?

The urgency with which this question was posed reflects the force of original drama of man versus machine. It is satisfying to imagine that the individual fighter might be triumphing over the mighty machine. But important as that it, we should not underestimate the novel technological dimension introduced by the ATGM.

With the ATGM, the superficially inferior physical equipment of the human body is more than compensated by the miraculous power of the technology in the human’s hands. You might think that this lowers the ideological stakes because it reduces the element of heroism involved, which is true. But for heroism it substitutes a more characteristically modern and indeed American ideology – the ideology of what British architectural critic and cultural theorist Rayner Banham called the gizmo or the gadget.

In an article in Industrial Design published in 1965, Banham define the gadget or gizmo as a

small self-contained unit of high performance in relation to its size and cost, whose function is to transform some undifferentiated set of circumstances to a condition nearer human desires. The minimum of skill is required in its installation and use, and it is independent of any physical or social infrastructure beyond that by which it may be ordered from catalogue and delivered to its prospective users.

The war in Ukraine figured as a battle of Ukrainian fighters v. Russian tanks, Javelin v. T72 has become a dramatic reaffirmation of Banham’s gizmo theory of modernity and American modernity in particular.

Training in the Javelin system usually takes 80 hours in the U.S. military but is being done in two days in Ukraine.

As Banham writes:

“The man who changed the face of America had a gizmo, a gadget, a gimmick – in his hand, in his back pocket, across the saddle, on his hip, in the trailer, round his neck, on his head, deep in a hardened silo. From the Franklin Stove .. through the Evinrude outboard to the walkie-talkie, … the most typical American way of improving the human situation has been by means of craft and usually compact little packages, either papered with patent numbers, or bearing their inventor’s name to a grateful posterity.”

Crucially, the gadget packs a punch, but it does so whilst giving its user apparent autonomy from the underlying infrastructure of society and the division of labour that actually sustains the economy and society at large. It is thus radically individualizing, designed for the encounter between an individual “man” – or a small group – and a hostile environment. As Banham puts it:

True sons of Archimedes, the Americans have gone one better … To move the earth he (Archimedes) required a lever long enough and somewhere to rest it – a gizmo and an infrastructure – but the great American gizmo can get by without any infrastructure. Had it needed one, it would never have won the West or opened up the transcontinental trails. The quintessential gadgetry of the pioneering frontiersman had to be carried across trackless country, set down in a wild place, and left to transform that hostile environment without skilled attention.

In his remarkable text, Banham derives the development of the gadget above all from the broader economic conditions of the United States. In particular he argues that industrialism in Europe developed against the backdrop of highly sophisticated agricultures which had subdued any remaining wilderness. By contrast, in the US an industrialized society directly encountered the wild and responded with the power of gadgets.

This is compelling but it is tempting to say that Banham underestimates the significance of war and the battlefield, a “man-made” wilderness, for the development of gadgets more generally. But setting that aside, once America’s gizmo habit developed Banham is absolutely explicit about the role of the gadget in US power projection in the world.

As Banham writes, in terms which could have been coined for our current moment:

Because practically every new, incomprehensible or hostile situation encountered by the growing American Nation was conquered, in practice, by handy gizmos of one sort or another, the grown Nation has tended to assume that all hostile situations will be solved by gadgets. If a US ally is in trouble, Uncle Sam rolls up the sleeves of his Arsenal-of-Democracy sweatshirt and starts packing arms in crates for shipment long before he thinks of sending soldiers or diplomats – and be it noted that it was a half-breed American, Winston Churchill, who responded in terms that were pure gizmo-culture: “Give us the tools and we’ll finish the job!”

Churchill’s comment, by the way, came in the course of the struggle to get the Lend Lease passed through Congress in the spring of 1941, a history which has been reanimated in the struggle with Russia in 2022. As Banham remarks:

Rand Corporation/Strangelove style revolves disproportionally around king-sized gadgets whose ballistic complexity and sheer tonnage should not blind us to the fat that they are still kissin’-cousins to Colt and Winchesters, and that the abstract concept of weaponry is simply Sears’ catalogue re-written in blood and radiation-sickness.

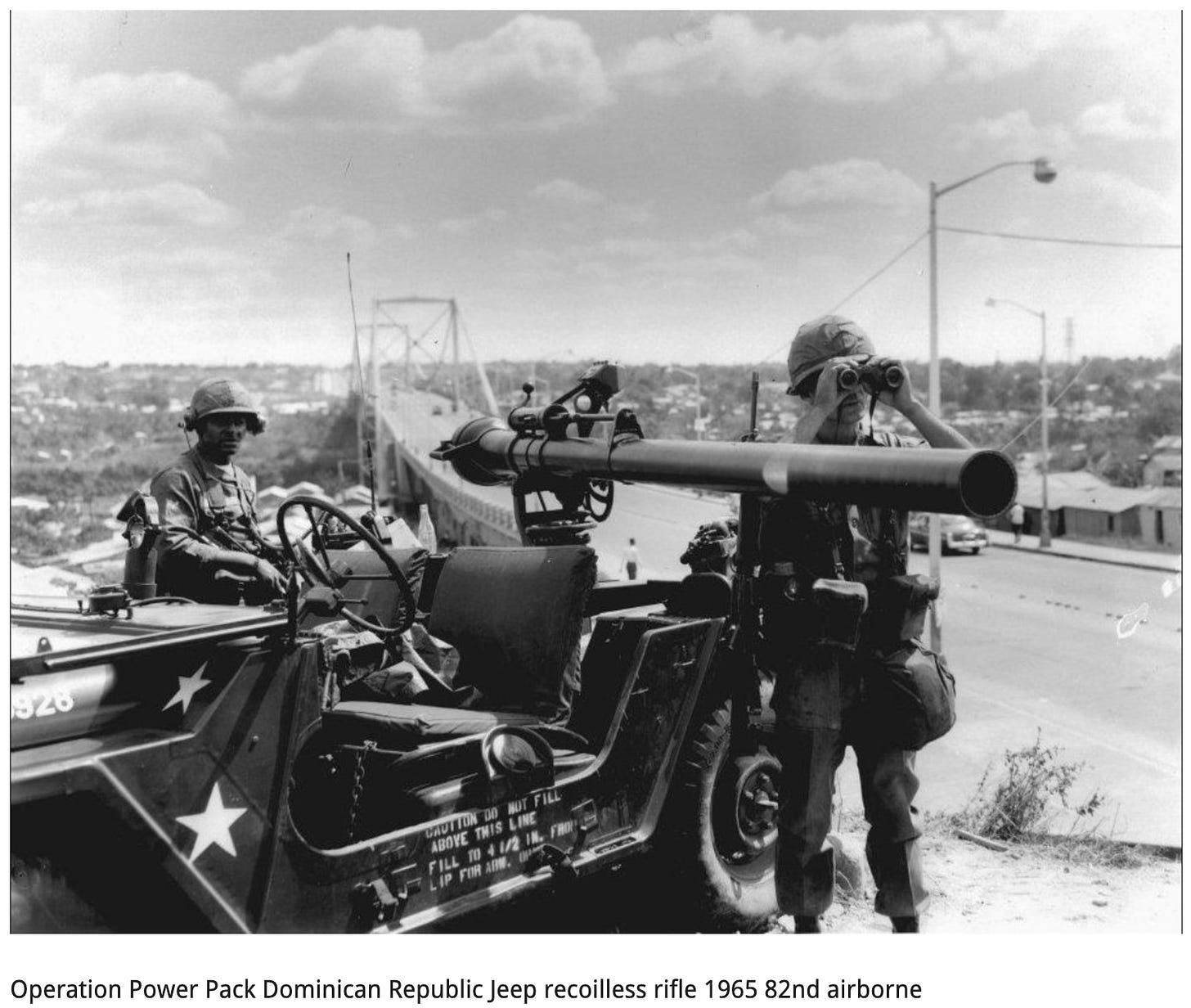

Ballistic missiles are gizmos but so too are anti-tank guided missiles. In one fleeting passage Banham even mentions the role that recoilless rifles – a light-weight form of anti tank gun – played in the American intervention in the Dominican Republic in 1965.

In true “gizmo” style the intervention in the Dominican Republic was named Operation Power Pack.

One could argue with Banham’s reading of the Gizmo in terms of an exclusive American national style. Dozens of counter examples come to mind – Swiss army knives, canning (French), etc etc etc. But one can hardly deny the force of his analysis and its continued actuality e.g. in the form of the smartphone or the laptop. Or its relevance to our situation today.

As Banham notes, gizmos and gadgets exist in a continuous dialectical relationship with dependence on infrastructure. The successful gizmo reduces this to a minimum, at least over a period of time. But it can never quite escape its dependence. Thus every effort to make gadgets more sophisticated risks making them less successful as enablers of autonomy.

Today on the battlefields of Ukraine, American instructors and their students are rigging together improvised power packs to enable them to train and fire their Javelin launchers for more than the factory-standard 4 hour battery life.

Russia and Ukraine’s relative performance is in this sense explicable in terms of their relative success in making their gadgets autonomous and capable of long-range action. Whereas St Javelin has arisen as the patron saint of military gizmos, Russia’s logistics and communications have failed.

But the success of Ukraine’s weapons also enables something else. Whereas the intensity and ferocity of close quarter combat – as in Mariupol – requires a new personality type and super-human levels of motivation, the long-range anti-tank guided missile allows combatants to preserve something closer to normality. This is the ultimate gift of America’s weapons.

As one American volunteer said to Yaroslav Trofimov the WSJ correspondent. “This is not a war of good versus evil but of normal versus evil,” he said. “Normal people were living normal lives, and then Russia decided to wage war on them.” What normal people do faced with this kind of emergency is to reach for a tool.

*****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options: