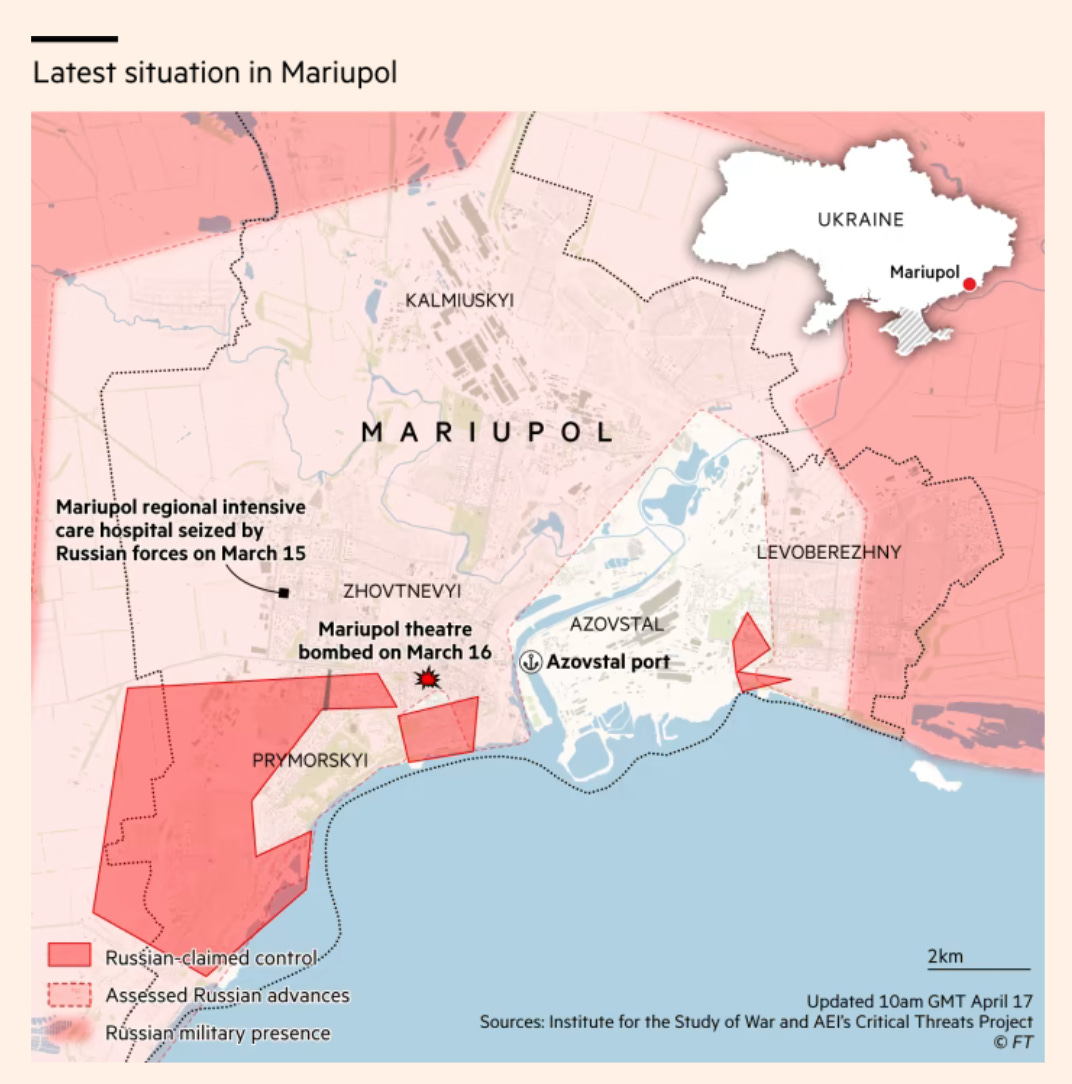

The vast complex of the steel mill of Azovstal is where the last defenders of Mariupol are making their stand.

What kind of place is this? A giant steel works sprawling over several square kilometers. It has tunnels in which the fighters are withstanding the bombardment. But how did it end up there? What brought us to this point of a factory fight in Southern Ukraine?

At moments like this, history truly reveals its quality as a pal·imp·sest – a manuscript or piece of writing on which the original writing has been effaced to make room for later writing but of which traces remain. The search functions of the internet reinforce that quality, constantly surfacing long-forgotten pieces from a different era.

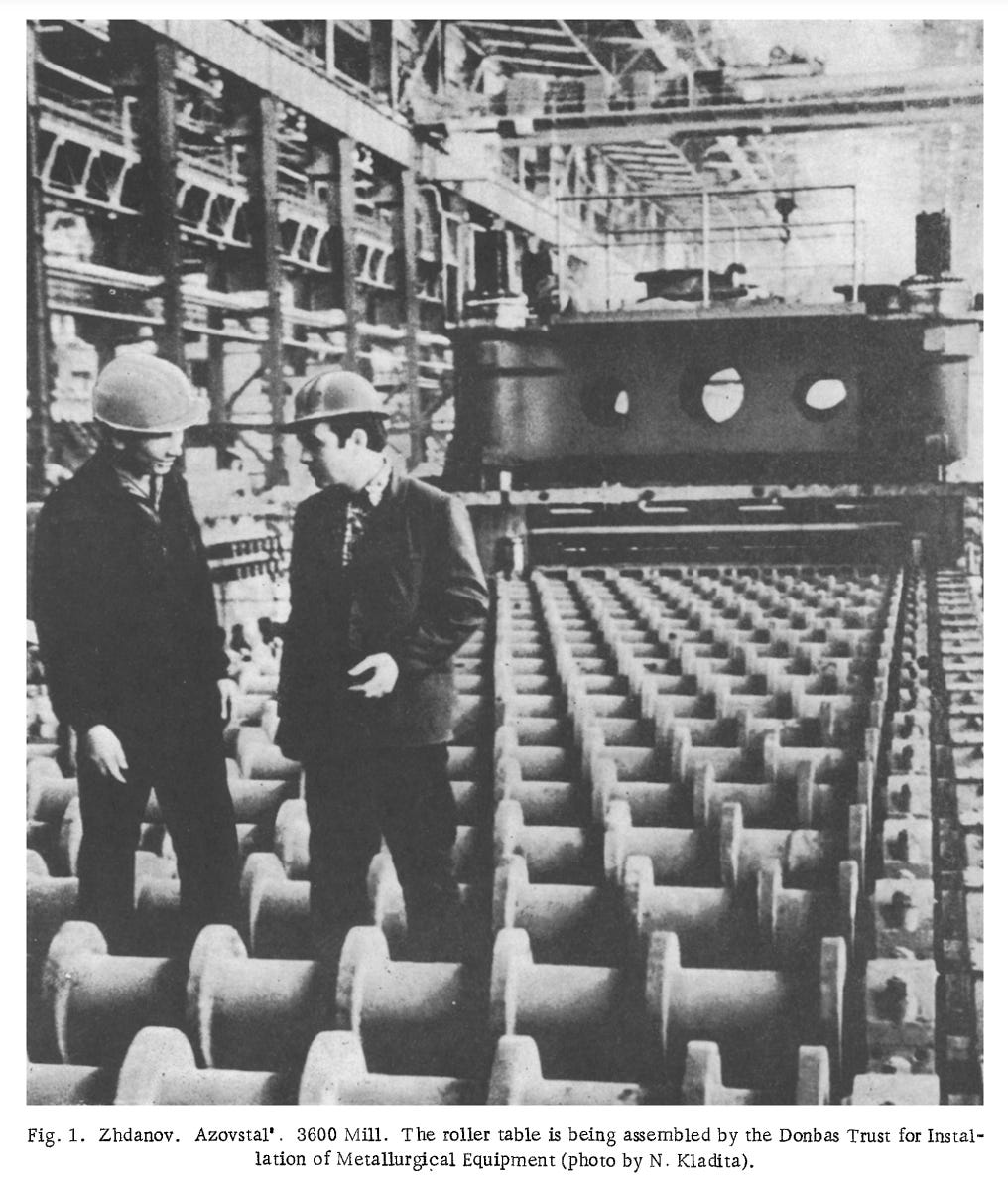

Google “Avostal”. You find this. From 1973 – the high-Soviet era.

A MOST IMPORTANT PROJECT OF THE THIRD, DECISIVE YEAR THE COUNTRY’S MOST POWERFUL 3600 MILL OF THE AZOVSTAL’ PLANT HAS PRODUCED THE FIRST SHEET Ya. Brodskii

Brodskii, writing in 1973 is already writing a history, looking back to the moment of Azovstal’s foundation in 1933:

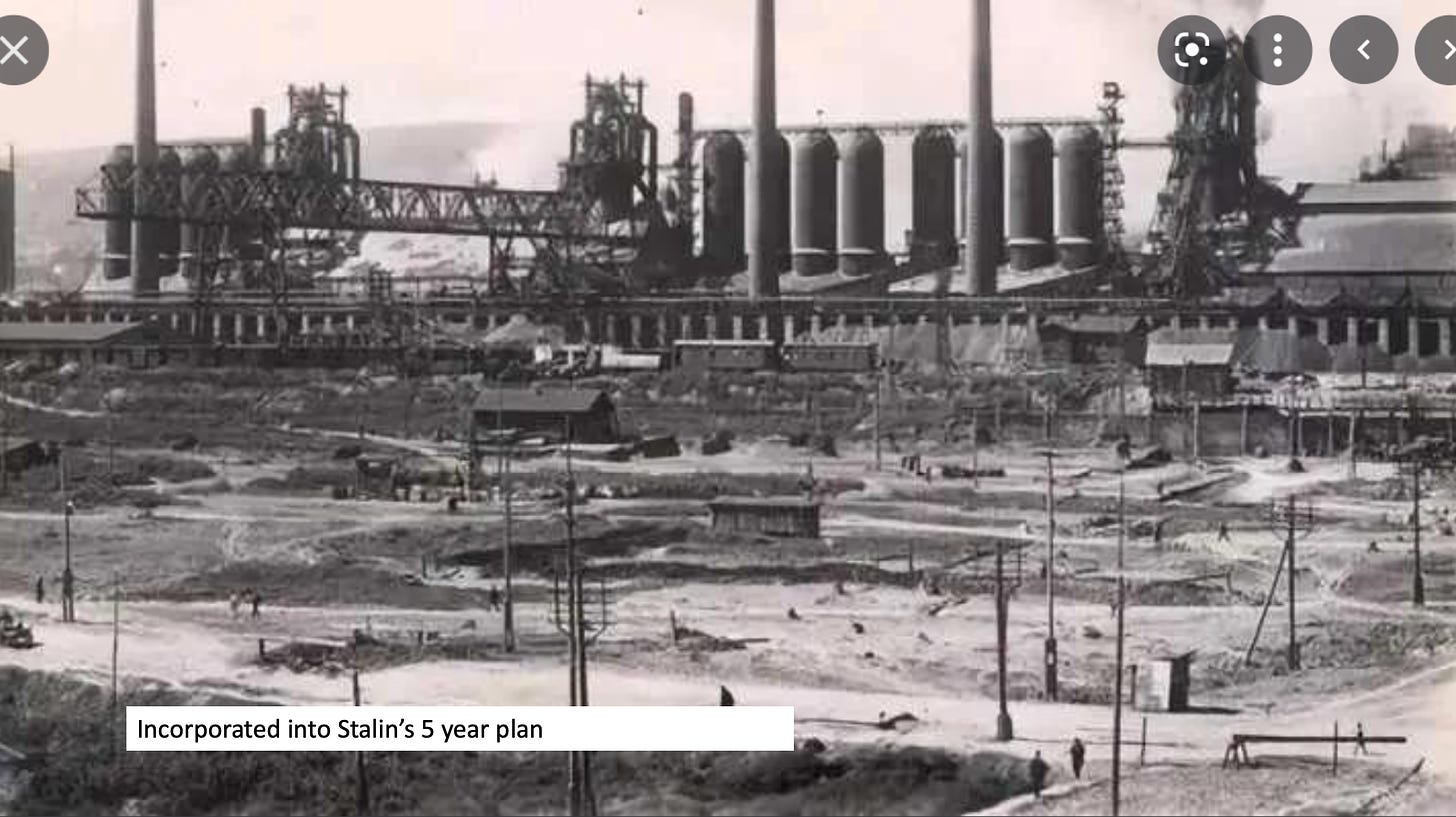

This was long ago – 40 years ago, during the years of the first five-year plans, years of romanticism and heroism, years that gave rise to the Magnitogorsk Metallurgical Combine, Kuznetsk, Dniepr hydroelectric station, Ural Heavy Machinery Plant… A country was being built, a country was being created. The words “first,” “first-born” were the most widespread at this unforgetable time. “First steel,* “first plant,” “first tractor !” We leaf through the pages of the newspapers of the 1930’s– these stern and impassioned chronicles of our life.

“Magnitogorsk– express telegram- on February 1 at 7:30 p.m. blast furnace No. 1 of the Magnitogorsk Metallurgical Combine produced the first pig iron.”

Knznetsk, April i. The incandescent blast is producing the first Kuznetsk metal. ~

“Makeevka, January 28. The first Soviet blooming mill passed the test perfectly.” …

So many ~firsts” appeared at that time … The first Soviet pig iron, tractors, blooming mills, steel, and automobiles were born in the foothills of the Ural mountains, in the spurs of Alatau, and on the shores of the Dniepr.

Azovstal’ Plant-‘SouthernMagnitogorsk” as it was called by people who arrived to build this metallurgical giant- rightfully numbers among the first-born of Soviet industry. The resolution of the Central Committe of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) on August 8, 1929, called for the immediate development of a plan for using Ketch ores and in connection with this the construction of plants in the Azov region. This resolution gave rise to the design and construction of the Azovstal’ Plant. … Tens of thousands of builders from Russia, Belorussia, Georgia, and Kazakhstan arrived at the shores of the Azov Sea to erect one of the countries most powerful metallurgical enterprises, the Azovstal’ Plant.

Ya. Gugel’, who a year before had constructed the Magnitogorsk Metallurgical Combine, directed the project. Every day brought news about the feats of labor of the builders. Record after record was established by the concrete workers, diggers, carpenters, and assemblers. And there, on August 10, 1933, the enormous bright red banner of the KIM (Communist Youth International), raised by the assemblers of Stepan Zumadzhi’s brigade, flew in the night sky above the top of the first blast furnace. And several hour later, at 3:44 a.m., the order was given to blow in the furnace. Thus began the life of still another first-born of Soviet industry. This was long ago, 40 years ago … And here, today, four decades later, we again speak about the heroic labor on the shores of the Azov Sea.

1930s USSR – Chief of Newly Built AZOVSTAL METALLURGICAL (Steel) PLANT

To imagine Azovstal’s birth, consult Stephen Kotkin’s Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization, the classic study of Magnitogorsk, which, according to legend, was inspired by taking office hours with Michel Foucault during a visit to Berkeley.

Azovstal was not the first steelworks at Mariupol (the city was renamed Zhdanov during the Stalinist era, after its most famous son). That honor belongs to the Ilych Metallurgical Complex (MIMC). As an anniversary piece noted:

The IMC enterprise was started on the basis of the works of the Nikopol’–Mariupol’ joint-stock company Providence. February 13, 1897, is considered the birthday of the IMC. On that day, the pipe shop produced its first real product, namely, pipes for laying the Baku–Batumi kerosene pipeline. In 1897, the openhearth furnaces and the rolling shops were put into operation. In 1898, the enterprise had already begun to operate according to the complete metallurgical cycle and it had become the largest works in the southern part of the Russian Empire. In 1914, for fulfilling largescale state orders, there had been put into operation a unique 4500 armoring rolling mill. After 1927, after nationalization and renewal, the works continued to develop as a polytechnical enterprise. In 1930, the first turn of the pipe-rolling shop, which had been the largest in Europe, was put into operation. During the years of the first 5-year plans, the works became the initiator and founder of rapid steelmaking practice; in 1935, it reached the first All-Union record in the steelmaking productivity; and in 1936, it achieved the world record in yield of steel from a square meter of the furnace hearth. In the prewar period, production of armor for the T-34 tank at the works, which played a noticeable role in winning the war with Germany, was perfected for the first time.

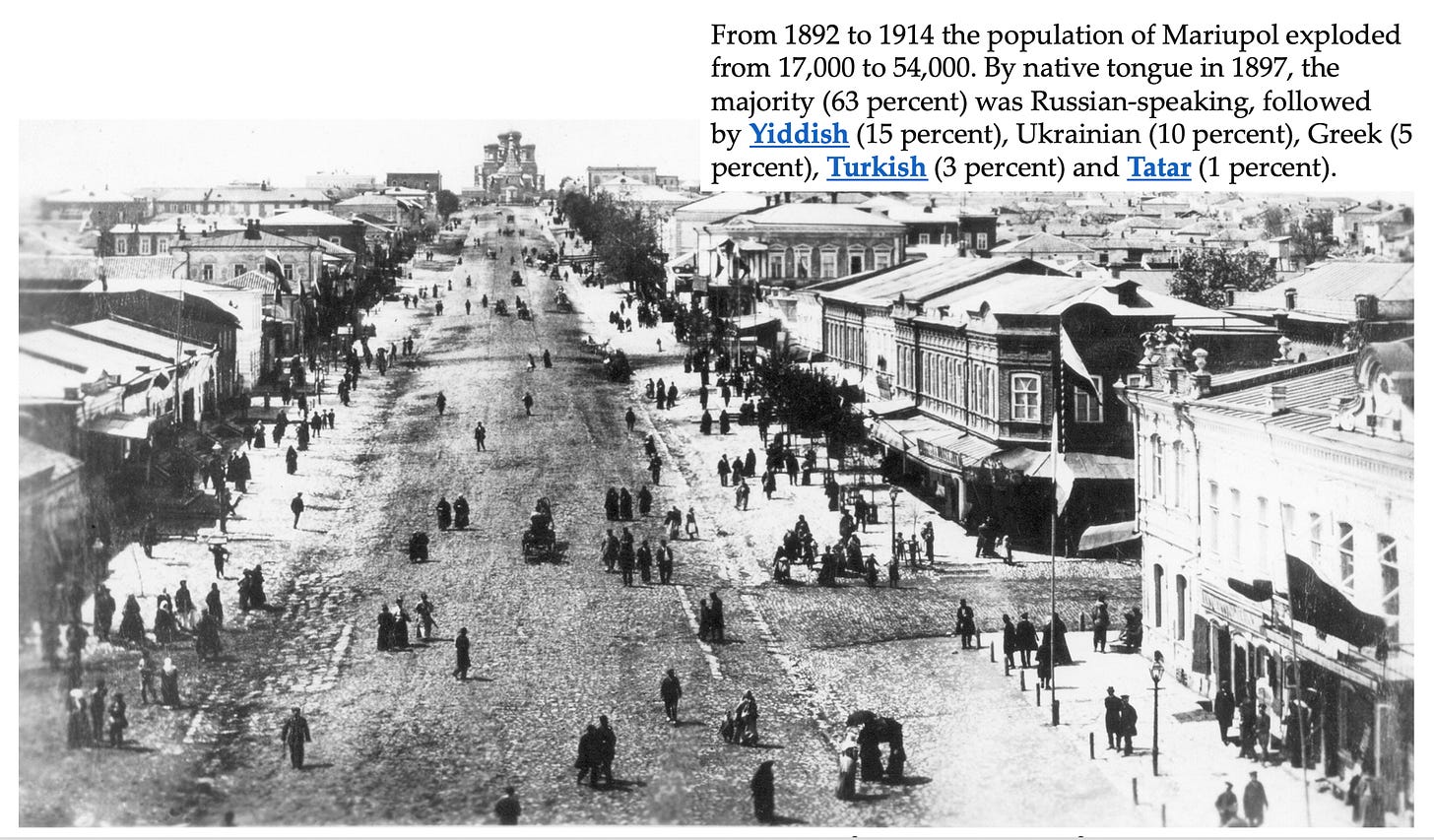

First the railway, then grain export, then steelmaking transformed the sleepy ethnically and culturally-Greek enclave of Mariupol first into a bustling Imperial Russian boom town and then into a Soviet construction site.

On Mariupol’s history the online Encylopedia of Ukraine is excellent.

In the late 19th century Mariupol was developed as a shipping port for the Donets Basin. In 1882 it was linked with Donetsk by railway, and in 1886–9 the commercial port was built. The main exports were coal and grain. By 1900 the port was handling 1 million t of freight, and the tonnage doubled in the next decade. At the turn of the century a tube-rolling and two metallurgical plants were built (the Nikopol, in 1897 by the American businessmen Rothstein and Smith, and the Russian Providence, in 1899 by a Belgian company). Easy access to raw materials, labor, and a port for export were the main attractions. From that time the town’s heavy industry grew rapidly.

From 1892 to 1897 the population of Mariupol almost doubled, from 17,000 to 31,100. By native tongue in 1897, the majority (63 percent) was Russian-speaking, followed by Yiddish (15 percent), Ukrainian (10 percent), Greek (5 percent), Turkish (3 percent) and Tatar (1 percent). By the beginning of the First World War the city’s population had jumped to 54,000.

As a later director of the Azovstal steelworks explained, what drew the people in was a peculiarly beneficial combination of raw materials:

The “Azovstal” Works makes use of the enormous deposits of phosphorus-containing Ketch ores which lie almost on the surface and are transported to the Works by the Azov sea after beneficiation and sintering, and of the Donets coal processed into high-grade coke at the coke and by-product plant. Limestone required for the blast furnace and the open-hearth furnace processes is obtained from the Elenovskie quarries, situated in the vicinity of the Works. Krivoi Rog ores are also employed in the blast-furnace charge. The Works is thus situated in the center of sources of raw materials

By 1939 under the impact of Soviet development, Mariupol’s population had surged to 227,000 – from 17,000 in 1892!

In 1941, the German invaders killed the Jewish population they could find, ruined the town and on their retreat laid waste to the steel plants. The population by 1943 came to only 85,000. The devastation the Germans left behind was total.

huge heaps of tens of thousands of tons of stones, lumps of concrete, mutilated steel structures and equipment were !ying all over the Works. In September, 1943, there was no water, electricity or steam either in Mariupol or at the Works. Under those difficult conditions the metallurgists of the ~Azovstal” and the constructors of the ~Azovstalstroi ~ began the reconstruction of their Works, The seemingly impossible task was accomplished with the help of the strong will and the courageous spirit of the Soviet people. In October, 1944, the power station was rebuilt and in July, 1945, No. 8 blast furnace was blown in.

The subequent reconstruction was dramatic, as V.V. Leporskii then plant director at Azovstal recalled in 1963.

A sintering mill, two blast-furnaces, six open-hearth furnaces, a large-capacity blooming mill, a rail-structural mill, a heavy grade mill, a ball-bearing mill, a mill for rail reinforcements, and others were built; the construction of housing, hospitals, schools, movie theatres, and culture palaces developed extensively. Construction has proceeded at a rapid pace. The 1940 level of production of iron and steel has now been exceeded several times; labor productivity per worker has increased by 4.7 times throughout the plant. The plant has been a profitable installation since 1960. …. In 1962 a collective of innovators of the plant won first place in the district competition, and in the All-Union contest in 1962 for introducing inventions the plant “Azovstal’ ” won third place. The cadres grow and improve with the plant. This year over 5 thousand persons are enrolled in institutes, technical schools, schools for advanced training, and industrial-technical courses.

As its workforce became more and more sophisticated, in 1973, the plant was celebrating the introduction of the first computer-controlled processes.

Computers, according to a prescribed program, monitor the heating of the slabs and control the operation of the stands and heat treatment of the sheet. In the future computers will be connected to the automatic production control system of the entire Azovstal’ Plant which is being created.

Source: COURSE OF THE AZOVSTAL ~ PLANT IN THE TENTH FIVE-YEAR PLAN A. M. Sedakov

The trail of Azovstal’s heroic commemoration goes cold in the 1980s and 1990s. As Kimitaka Matsuzato of Tokyo University explains in her excellent essay on Mairupol’s local politics, the city stagnated amidst the overindustrialization of the late Soviet period.

In 1993, the sixtieth anniversary of the plant, V.A. Sakhno published an almost apologetic piece noting:

The combine is now encountering problems in producing metal with prescribed properties. While the product mix is becoming more complex, Azovstal’ is having difficulties obtaining charge materials of consistently high quality. The same holds for deoxidizers and alloying additions. It has also become necessary to significantly reduce energy consumption during steel production. At the same time, clients are demanding metal of higher quality

And then, the oligarchic power struggles of the Donbas broke loose. In November 1996 Mariupol’s two steelworks, long-time competitors, were suddenly merged into a single conglomerate. As the Steel Times reported, the local population were dumbfounded.

Ukrainians ‘taken aback’ by Azovstal/Ilyitsh merger Steel Times; London Vol. 224, Iss. 11, (Nov 1996): 383.

By the early 2000s the owner of the former crown jewel of Soviet industrialism, Azovstal, was Rinat Akhmetov, perhaps the richest of Ukraine’s oligarchs and certainly one its toughest. As Leonid Bershidsky, Bloomberg’s columnist described it:

In early 2014, Mariupol was a typical mid-sized post-Soviet industrial city, dominated by two major steelworks, both under the control of the country’s richest oligarch, Rinat Akhmetov, and the port used to export their output. …. Backed by Akhmetov’s political clout and resources, the Party of Regions of then-president Viktor Yanukovych held sway. The population, including tens of thousands of Azov Greeks — descendants of the city’s 18th-century Orthodox Christian founders, resettled by Russia from still-independent, Muslim-run Crimea — was predominantly Russian-speaking and had little to do with Ukrainian ethnicity or culture.

In short, it was the kind of city that fit in nicely with semi-official plans by some Kremlin officials and ethnonationalist ideologues in Russia to create a separatist state called Novorossiya in eastern and southern Ukraine. During the chaotic spring of 2014, thousand-strong mobs hunted through the city for Ukrainian nationalists supposedly sent from the country’s west to suppress them, the city council building was seized by rebels who flew Russian flags from it, and a gun battle took place for the police headquarters. The post-revolutionary Ukrainian authorities were too weak to re-establish order quickly, and it fell to local irregulars, some of them ultranationalists with openly racist views and swastika tattoos, to fight off the Communists and pro-Russian activists who sought to make Mariupol, located in the Donetsk Region, part of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic. ….

Somehow Mariupol avoided being taken by the separatists. ….

In early 2015, with the war in eastern Ukraine still in its active phase, the eastern suburb of Mariupol came under heavy shelling from the separatist side, and dozens of civilians died (Akhmetov stepped in with a large personal donation to repair the damaged infrastructure). That brought home to the residents that their city was now on the front line for the long term. But when a ceasefire negotiated in Minsk took effect later that year, the relative benefits of this status began to manifest themselves. With eastern Ukraine’s biggest city, Donetsk, under separatist control, Mariupol became the center of the region’s Ukrainian part, and the administrations of both Petro Poroshenko and Volodymyr Zelenskiy have sought to turn it into a showcase of what the Donbas could become under Ukrainian authority.

Akhmetov is a pivotal figure in Ukrainian politics. In 2021 an open trial of strength appeared to have begun with President Zelensky and the parliament. The Rada passed legislation threatening to crack down on oligarchs, raise taxes and railway fees. Akhmetov was accused by Zelensky of plotting a coup against him.

With the invasion, however, Akhmetov has committed to the national cause. As CNN reports

Ukraine’s richest man has pledged to help rebuild the besieged city of Mariupol, a place close to his heart where he owns two vast steelworks that he says will once again compete globally. For now, though, his Metinvest company, Ukraine’s biggest steelmaker, has announced it cannot deliver its supply contracts and while his financial and industrial SCM Group is servicing its debt obligations, his private power producer DTEK “has optimised payment of its debts” in an agreement with creditors.

“Mariupol is a global tragedy and a global example of heroism. For me, Mariupol has been and will always be a Ukrainian city,” Akhmetov said in written answers to questions from Reuters.

On Friday, Metinvest said it would never operate under Russian occupation and that the Mariupol siege had disabled more than a third of Ukraine’s metallurgy production capacity.

Akhmetov praised President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s “passion and professionalism” during the war, seemingly smoothing relations after the Ukrainian leader last year said plotters hoping to overthrow his government had tried to involve the businessman.

Akhmetov called the allegation “an absolute lie” at the time.

“And the war is certainly not the time to be at odds… We will rebuild the entire Ukraine,” he said, adding that he returned to the country on Feb. 23 and had been there ever since.

Akhmetov did not say where exactly he was, but that he had been in Mariupol on Feb. 16, the day some western intelligence services had expected the invasion to begin. “I talked to people in the streets, I met with workers…,” he said.

“My ambition is to return to a Ukrainian Mariupol and implement our (new production) plans so that Mariupol-produced steel can compete in global markets as before.”

“I am confident that, as the country’s biggest private business, SCM will play a key role in the post-war reconstruction of Ukraine,” he said, citing officials as saying the damage from the war has reached $1 trillion.

“We will definitely need an unprecedented international reconstruction programme, a Marshall Plan for Ukraine,” he said, in reference to the U.S. aid project that helped rebuild Western Europe after World War Two.

“I trust that we all will rebuild a free, European, democratic, and successful Ukraine after our victory in this war.”

Whilst Akhmetov sees a future for Azovsteel as the site of yet another industrial renaissance this time under a Ukrainian Marshall Plan, in the tunnels of his factory, Ukrainian marines of the 36th brigade, a large number of Azov brigade combatants, soldiers from the 56th Infantry Brigade, as well as border guards and volunteer fighters are, to all appearances, preparing to fight to the last bullet.

What they seem to be enacting is not the Marshall Plan, but something closer to Stalingrad.