War and history are intertwined. Entire conceptions of history are defined by what status one accords to war in one’s theory of change. War is certainly not the only way to punctuate history, but it is clearly one of the pacemakers. Battles and campaigns are not the only events that define winners and losers, but they do matter. In its heyday war was the great engine of history.

One of humanity’s recurring hopes has been that through history we might escape war. Since World War II Western Europe in particular has been invested in the idea of consigning war to the past. That is a hope that is based not just on a humanitarian impulse, but also on the sense that the basic questions of international politics were resolved and that for the settlement of whatever remained, the modern instruments of war – most notably nuclear weapons – were likely counterproductive. The era of military history was thus consigned to an earlier developmental phase.

If it was once sensible to think of war as the extension of policy by other means, historical development had closed that chapter. Both the main questions of policy and the repertoire of sensible policy tools have changed. With the passing of that epoch, war belonged to the past. Skepticism about war was not, first and foremost, a matter of moral values, it was a matter of realism, of understanding what actually made the modern world tick.

From this point of view, if major powers did “still” engage in war – as many regrettably did – it was either a sign that they were regressing to an earlier stage of statecraft, under the malign influence of reactionary elites. Or the elites in question had fundamentally miscalculated, not grasping the real stakes, or the proper means with which to pursue their best interest. Or the war in question was simply not very important, less a historic turning point than an atavistic indulgence. “Wars of choice” are an occasion to show off the raw power of the state without facing serious resistance.

All three modes of interpretation could be brought to bear on what to date was the biggest war engaged in by major powers in the post-Cold War period – the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Russia’s assault on Ukraine is shocking, therefore, not only for its violence, but for the fact that it reopens the question of war as such and thus also the question of history.

The weight of this question first impressed itself on me in the third week of February – in that blessed interval when it seemed that the COVID pandemic in NYC had passed, but before Putin actually launched his attack on Ukraine.

To be specific it was on Tuesday 22nd February when I had the pleasure of discussing the daring new book by Alex Hochuli, George Hoare and Philip Cunliffe, The End of the End of History, with one of its authors, Alex Hochuli.

It was a particular pleasure to debate with Alex Hochuli because he and I had previously gone back and forth on his “Brazilianization”-thesis of the 21st century.

In the End of the End of History, Hochuli, Hoare and Cunliffe offer a daring rereading of Fukuyama’s end of history thesis. They spell out the class politics of the end of history, the depoliticizing logic of neoliberalism and postulate a dynamic through which it will be surpassed and overcome. The supposed conclusion of history in which all fundamental ideological conflicts are resolved, produces, they suggest, its own gravediggers.

Silvio Berlusconi, the Italian media mogul and prime minister with his notorious “Bunga parties”, is for them both an archetypal figure of the end of history and an emblem of the fact that that epoch cannot endure. We are all caught up, as they gloriously put it, in “Aufhebunga Bunga”, a bit of Dada-theory doggerel that one hopes will enter the general vocabulary.

On that tip, their podcast Bungacast, is great listening.

But, if it is true that history has a tendency to restart, the question is, what key will it restart in?

Working from a Marxist framework, Alex and his co-authors pose the question of politics and history above all against the background of class analysis. Can the neoliberal paralysis of politics and history really endure? Will it not, in the end be destabilized and blown open by an insurgency of what they call “the masses”? Is so-called populism one of the forms that explosion will take?

Alex and I had a fascinating exchange about their class analysis and this takes up most of the time in the video. But I will admit that my mind that evening was on the possibility of something even more urgent. Speaking to military analysts earlier in the week it had been born in upon me that Russia’s forces were poised to attack.

What if history was restarted but on the other axis of modern history-making? Not class struggle, but war? And, if so, what kind of war would it be? This was the question I started wrestling as of minute 39 in the video. That question would be answered on February 24, two days later.

Following the conversation with Alex Hochuli, Gavin Jacobson, another avid reader of Fukuyama, asked me to elaborate on the question of war at the end of history. What came out is the essay that appeared this week in the New Statesman.

The original starting point for the essay was the fact that, as Gavin reminded me, in the final chapter of The End of History, Francis Fukuyama had anticipated a strong-man figure who might want to overturn the end of history by force majeure. This figure would want to restart the struggles of the past, to restore meaning and humanity to existence, almost regardless of ideological content. It would be the struggle for status that mattered, per se.

That ran contrary to Stephen Kotkin who reads Putin as a direct descendant of the lineage Russian expansionism that goes back to Ivan the Terrible.

Others have labeled Putin as a “19th-century man” stuck in a 21st-century world.

I am not convinced by any of these interpretations. Let us not grant to Putin and his war such a distinguished pedigree or such radical intent. Let us instead locate Putin where be belongs. In our epoch. Whether we like it or not, Putin is our contemporary.

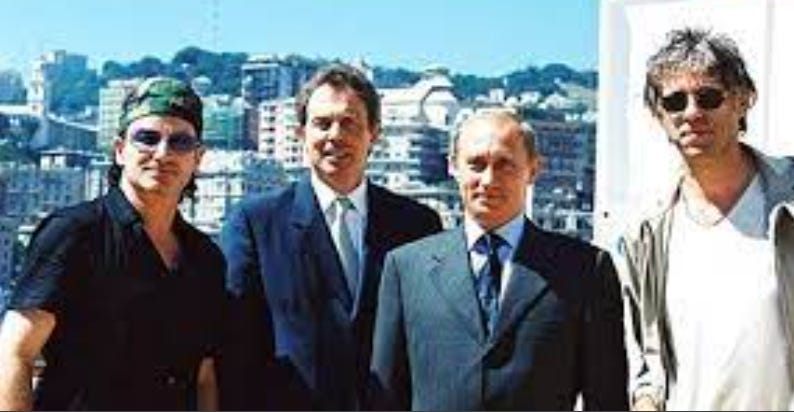

Putin with Bono, Blair and Bob Geldof, from the Russian Presidential website.

As the war in Ukraine was originally conceived, it was, as I put it somewhat flippantly on February 22nd, a “Bunga war” – frivolous, gratuitous, neither a serious act of great power politics, nor a dramatic effort to restart history.

The original invasion plan, possibly cooked up by intelligence officials rather than soldiers, seems to have been to seize Kyiv, the Presidential offices and the TV stations by a coup de main. That failed. And then Plan B, the large scale air assault and standard Red Army encirclement of Kyiv, also failed.

That has left Putin fighting for his own regime’s survival, his military flailing, a war consisting less of coherent operations than a string of atrocities. Whatever the flow of battle on the ground, Russia has lost the ability to control the narrative through which the war is made sense of outside Russia’s own immediate orbit.

The really interesting thing is not so much Russia’s intent, but why it failed. In part it was incompetence and bad planning. Many of the Russian soldiers do not seem to have realized that they were actually engaged in an invasion at all – a Bunga syndrome if ever there was one. Propagandistic pastiche and violent reality merged completely in a manner reminiscent in some ways of the January 6th riot in Washington DC.

The harsh reality that Russia’s dazed invaders came up against – at least as far as our media allow us to glimpse it – was Ukrainian resistance backed by unexpectedly significant support by NATO.

So if the Ukraine war marks a a break, to put the emphasis on Putin may be misguided. If the honor of rekindling history, of “returning us to the 19th century” belongs to anyone, it is not to Bunga-Putin. That honor belongs to the Ukrainians.

It is the Ukrainians, to the amazement and not inconsiderable embarrassment of the West, who are enacting a drama of national resistance unto death. Under Russian attack, they are bonding together and demanding recognition of their sovereignty. There are many other peoples who are struggling for their existence and recognition today. The difference is that the Ukrainians do so in the classic form of a nation in arms rallying around a nation state. And the Ukrainians do so efficaciously. They have turned back a Russian army. They have saved their capital city. Those are not merely symbolic achievements.

Looking back at the conversation with Alex Hochuli I cannot but think of one of the most impressive passages in their book, which I quoted to him on the evening of February 22nd.

Hegel’s claim about the End of History did not rest on the durability and stasis of the post-Napoleonic settlement, but rather on the irreversible character of certain historic developments with respect to our collective self-understanding. Most important of these was the universality of freedom within the modern world that had been unleashed by the French Revolution. In Hegel’s view, the specific historic gain of the French Revolution was to reveal the universal character of human freedom, that is, the claim that freedom is in fact part of being human. Freedom was thus not merely an abstract philosophical proposition, but a political proposition that could be realized in concrete institutions. This was Hegel’s original meaning of the End of History – that whatever followed the French Revolution had to be based on the universal claims of human freedom. This in turn meant that no social or political order could ever be fully stable. The significance of this insight is that freedom cannot be limited or appended to one specific regime or order, as it is precisely the expansiveness and restlessness of human freedom that exceeds any one specific set of political and social institutions. It is this that explains how there can be a finality to the historic process – after the French Revolution, the irreversible and simultaneously contradictory character of human freedom serves as a backstop to history … Hegel’s real insight is that no order founded on human freedom can be ossified; all ends of history end, all modern political orders are eventually remade.

Hochuli, Alex; Hoare, George. The End of the End of History (pp. 33-34). John Hunt Publishing. Kindle Edition.

If Hegel talked of freedom in a collective sense, is it not likely that he had, amongst other things, in mind the example of the French revolutionary wars and Napoleonic wars? And to that degree is it not legitimate to extrapolate to the struggle of Ukraine today?

When we talked that evening in February, neither Alex or I – I think – conceived of what was to come next. (Read the book, watch the video and judge for yourselves). I spoke about war, but I anticipated a “Bunga war”, a brutal show of Russian force that crushed Ukraine. What we did not anticipate was a protracted and successful struggle for survival that would put Putin too at existential risk.

With Russia and Ukraine locked in battle, the question becomes how will the Western powers respond? It is up to them/us! As I put it in the New Statesman article, the End of the End of History will be what we make of it. That is what is at stake both in the war and even more in the peacemaking that must follow. How will order and freedom be combined in Europe?

For their interesting reading of Hegel, by the way, Hochuli, Hoare and Cunliffe draw on Todd McGowan’s book on Hegel, Emancipation after Hegel: Achieving a Contradictory Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.

For my own part, this exchange with Alex Hochuli and Gavin Jacobson brought me back to an interest in Fukuyama’s end of history thesis that goes back to the early 2000s. In particular Perry Anderson’s reading of Fukuyama in Zones of Engagement changed the course of my intellectual life.

The most immediate impact was in the form of a course that I taught at Cambridge in 2006 and 2007 that built a series of sessions around the dialectic that Anderson traces from voluntarism – the sense of being able to make history by an act of will – to exhaustion of historical agency, at the end of history.

It was a fun course. The session titles were as follows:

- Making History: The Hegelian Marxism of Lukacs, Gramsci, Gentile

- The End of History: Kojeve’s Hegel, Stalinism and the new Europe

- Terror and the open-endedness of history: Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, Camus, Merleau-Ponty

- Nazism and the eclipse of reason: Architects of Annihilation and the Dialectic of the Enlightenment

- Modernizing Europe, Convergence, End of Ideology

- From History to Biology: Herbert Marcuse

- History restarts? 1968-1978 The Crisis of Governability

- 1989: Another ending

You can download the full syllabus here. Making History, Ending History Dec 2006

****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But it is voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters that sustain the effort. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options: