“The consciousness that I live in a revolutionary world is the central fact in my life. I go to sleep and I awake thinking of the world in which I live. My whole personal life has become in a profound sense of secondary importance, and indeed, it, so immediate and so practical, is the part which is dream-like and unreal, and the other, more remote, touching me personally so little, is the imminent, the overwhelming reality. At the center of what I know is the realization and the acceptance of the certainty that never in my lifetime will I live again in the world in which I was born and grew to maturity.”

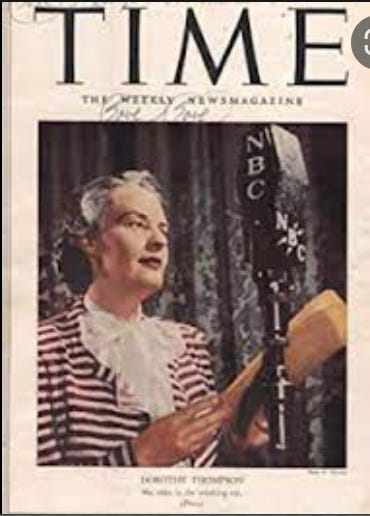

These words were written by Dorothy Thompson in January 1937 in an essay titled, “The Dilemma of the Liberal” published in Story magazine.

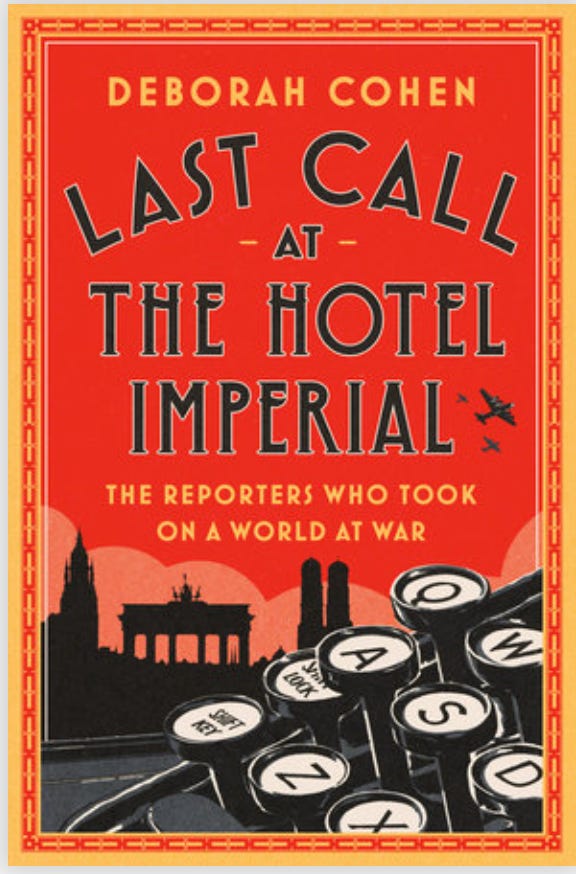

Thompson was at the time one of the most influential and well-known journalists and commentators in the world. She was at the center of a group of American foreign correspondents, sometimes associated with the “lost generation”, who reshaped American understanding of world politics and foreign affairs in the interwar period. Thompson is at the center of a complex web of personal, professional and political relationships unpicked with exquisite care and insight by Deborah Cohen in her wonderful new book, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial.

Any new book by Deborah Cohen is an event. Family Secrets and Household Golds were extraordinary displays of historical imagination and intellectual creativity, opening up the past in new ways.

Last Call has all the hallmarks of Cohen’s craft but to my mind it also has a singular urgency. It is also, it should be said, entertaining and at times moving.

So why does it matter?

Dorothy Thompson, Vincent Sheean, H.R. Knickerbocker, John and Frances Gunther traveled interwar Europe, Middle East and Asia. They were connected. They interviewed everyone. And at the same time they experimented in flamboyant ways in their private lives.

As Cohen recounts:

Steven Marcus (in a review of Sheean’s Dorothy & Red) judges both Thompson and Lewis as entirely externalized people – “abstract and depersonalized,” calling their marriage “more like a treaty or trade agreement between two minor nations than what is usually thought of as a marriage.”

And, as Last Call brilliantly shows, they struggled to related the public and private spheres of their existence and to historicize the relationship between the two. As Dorothy Thompson remarked in “The Dilemma of the Liberal”:

This life which you lead, a voice says to me continually, is in the deepest sense senseless; a repetition of social gestures, somehow hollow; it ties to noting, it is part of nothing. It is a dream, and the reality lies elsewhere … this nucleus, myself, my husband, my child, the people dependent on us and our friends, should somehow tie up and be part of a larger collective life, be integrated with it thorough and through. My parents’ life was. They were adjusted to themselves and to society. But the security of our world stops at our doorstep. “I am wounded in my fundamental societal impulses,” cries a man of genius, of my generation, in a burst of agony. What D.H. Lawrence felt, I feel, continually, overwhelmingly. It is not enough to say that he was an ill man we are both neurotics. Or rather, this neuroticism, if it be such, is epidemic. … I am giving publicity to my symptoms only because they are endemic, I believe, to the largest section of western intellectuals.”

This tension was a dilemma for Thompson as a self-identified liberal, because her sense of being wounded in her “fundamental societal impulses” made her sympathetic to an uncomfortable degree with the more radical politics of the era.

“… I could not accept the communist doctrine, still less could I accept the Nazi … Yet I share the discontent with existing society which made both movements possible. I cannot read half the newspapers or see the average Hollywood film without feeling ever so little like a Nazi, or observe the irresponsible antics of some of the rich, without feeling like a communist.”

Of the Communists she remarked,

I whom individualism and skepticism had set adrift in a world where everything was challenged and nothing believed, was drawn to these taut young people almost enviously.

And it was not just a psychological or emotional attraction. There was also a hard political lesson. Thompson had witnessed the fall of the Weimar Republic close up, but what really moved here was the destruction of Austrian social democracy in 1934.

When, later, the guns were turned against Vienna Social Democrats, and destroyed the only society I have seen since the war which seemed to promise evolution toward a more decent, humane, and worthy existence in which the past was integrated with the future, real fear overcame me, and now never leaves me. In one place only I had seen a New Deal singularly intelligent, remarkably tolerant, and amazingly successful. It was destroyed precisely because it was insufficiently ruthless, insufficiently brutal. “Victory” (I saw) requires force to sustain victory. I had wanted victory, and peace.

Something else was required.

Ultimately, it is tempting to say that Thompson’s extraordinarily prominent role in America’s war effort in World War II, would bring her the closure that she craved in her 1937 essay.

The war would catapult other individualist and skeptical intellectuals too into a convulsive embrace of history. In France one thinks, immediately, of Sartre, de Beauvoir and Merleau-Ponty.

Fascinating as the Parisian super stars are, it is tempting to say that their extraordinary intellectualism makes them less representative of broader patterns of change. Most people did not negotiate the shock by way of Heidegger, phenomenology, or Kojeve’s reading of the master-slave dialectic.

By contrast, Deborah Cohen’s group are eminently relatable. They were part of a new cohort of College-educated men and women. They wrote for a broader audiences in fluent and accessible prose. And as Cohen’s deft reading reveals, this signified something quite fundamental.

In his classic text, Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origina and Spread of Nationalism, Benedict Anderson explained how in the late 18th and early 19th century, the genres of the novel and the newspaper had helped enroll their readers in a new communal understanding of time. As Anderson, the anthropologist, saw it, a temporal frame defined by religion and monarchical sovereignty was replaced by a new perception of continuous, but eventful historical time. Individuals came to understand themselves as belonging to communities that progressed through history as quasi-organic wholes, in which individual mortality was subsumed in a collective immortality. No one could escape the collective story but it was also the ultimate source of meaning.

If the emergence of collective historical consciousness in its modern sense can be dated to what Reinhart Koselleck called the “saddle period” around 1800, what Cohen shows us is how in the early 20th century the nexus between history, the collectivity and the individual was disturbed for a second time.

Nineteenth-century certainties were blown apart by the explosion of violence and of economic crisis unleashed by World War I, which threw visions of regular historical development into question. At the same time the nexus of individual and collectivity was also disturbed by the putting into question of individual subjectivity by the widespread popularity of notions derived from Freudian psychoanalysis and a fundamental renegotiation of gender roles, sexual desire and identities.

A century on from the Anderson/Koselleck moment, the relationship between the individual and the collective was in flux. As Cohen notes, this was also a central preoccupation of the pragmatist movement, as exemplified by John Dewey.

The whirlwind of the individual and collective was all the more destabilizing for the fact that individual men had suddenly come to take on a larger than life importance in world history. As Cohen puts it:

liberals or conservatives (had not, AT) devoted much attention to the transformative power of the individual leader. 7 No matter how powerful politicians such as David Lloyd George or Raymond Poincaré were, they represented the distillation of the energies of their parties and their people. In that sense, they were interchangeable with another statesman. 8 But by the early 1930s, when Knick and John feuded in a Vienna café, it was clear that the “authority of personality,” as Hitler put it, mattered more than it ever had in their lifetimes. 9 One couldn’t account for what was happening otherwise. The individual leader, as Knick wrote, now counted for “nearly everything.” 10 They were the ones fomenting the world crisis: it was happening within them and through them. When the fate of the world hinged upon a handful of men, personal pathologies became the stuff of geopolitics. The correspondents needed a new way of thinking about the role of the individual.

One might take issue with this juxtaposition between liberal politicians and the personalistic fascist “leaders” of the interwar period. Lloyd George and Clemenceau were both charismatic figures in their own right and acknowledged as precursors by Mussolini and Hitler.

The fascists thought of themselves as giving their states the kind of personalistic leadership, which Britain and France had benefit from, but Italy and Germany had lacked in World War I.

But the point is well taken. One of the great challenges of comprehending interwar history is how to craft a general narrative of history if it depends on individual personalities to this degree.

John Gunther in particular developed an overarching theory of history shocked into motion by the happenstance of individual personality. As Cohen suggests there is an interesting contrast between Gunther’s understanding of history and that being developed at the time by anthropologists like Margaret Mead that also centered on questions of character.

The contrast with the work of contemporary social scientists, notably the anthropologist Margaret Mead, is striking. 67 Mead and her colleagues were trying to understand the workings of national character: why – say – the Germans submitted willingly to dictatorship or the Americans demonstrated a stubborn, wary, independence. Such “culture-cracking,” they believed, could be marshalled to defuse international rivalries, or to win a war. Their analysis, like John’s, was indebted to a sort of Freudianism, requiring the investigation of child-rearing practices and generational friction. However, the sense of what mattered most was very different. As John Gunther saw it, individual personality had jolted history into a new gear. He was making an argument about accident rather than deeply ingrained patterns of culture.

On Mead’s work, Peter Mandler’s Return from the Natives How Margaret Mead Won the Second World War and Lost the Cold War is brilliantly illuminating.

Whereas correspondents like Gunther and Knickerbocker tended to preserve the dignity of their interviewees by not probing too deeply – their access depended on being at least minimally polite – and thus tended to reinscribe the importance of the great man, others in their circle were more skeptical. Frances Gunther, who is the pivot of much of Cohen’s narrative, was particularly impatient with her husband’s superficial treatment of the great figures of the day.

Frances was a Marxist but she was also a Freudian, which meant that she thought that an investigation of personality in light of the formative experiences of childhood was imperative. But she thought John and his friends were going about it the wrong way. For one thing, they were far too cautious about what they put in print. Why wouldn’t they just write the truth – that Poland’s Marshal Piłsudski was subject to psychopathic temper tantrums and Turkey’s Kemal Atatürk was a mother-fixated drunk? 47 Tear the veil off the dictators, she urged her husband.

Even more scathing was Vincent Sheean, who was both the most hell-raising and wildly experimental of the group and perhaps the most profound in his struggle with the intertwining of history and subjectivity. Amongst his diverse bibliography is a translation of Croce’s Germany and Europe.

Sheean more than any of the group experienced the radical blurring of the boundaries between the personal and the political. Whereas Thompson was suffering from a sense of malaise in the late 1930s, the news from Spain triggered in Sheean a full blown psychosomatic collapse.

That month, devastated by the events in Spain, Jimmy collapsed in Ireland. He and Dinah, and their two-month-old baby, were staying at a friend’s country house in County Meath. Years later, when Jimmy told the story, he readily acknowledged he’d been on a drinking binge. But that didn’t even begin to explain the whole thing, he insisted. To account for what happened to him, you had to understand about Spain. The nervous breakdown came first. The night that Franco launched his coup attempt, Jimmy was off his head, delusional, bellowing at the top of his voice. The Irish doctors had him sedated and when that wasn’t enough, they bundled him into a straitjacket. Next came his physical collapse. He frothed thick yellow at the mouth for days; he was burning up with a fever. In succession, his lungs, liver and kidneys failed, and in a Dublin hospital, he slipped into a coma. 105

Improbably given his lifestyle, Sheean outlived all the other members of the group. In 1963 he would begin the work of unpicking and analyzing the relationships that bound together his contemporaries with his warts and all biography of Dorothy Thompson and Sinclair Lewis, Dorothy and Red (1963). But the book that made his name and framed the question that Cohen so brilliantly expounds, is Sheean’s Personal History (1934). As Cohen aptly summarizes it,

It was a coming-of-age story, his own and the world’s, brought together. He was mapping his own development as an individual onto the world crisis. The young American sheds the insularity of his station and upbringing to experience events for himself. He arrives in an Old World where the Victorian certainties – about the legitimacy of European empires, the beneficence of capitalism and free trade, the inevitability of progress – are in tatters. Through his reporting, he takes the measure of the new forces rising: the power of collectivism, especially Communism, and the strivings of colonial nationalism. Eyewitness to violent battles on the periphery, he sees that the twentieth-century movements are uncontainable and that the old order of class inequality and imperial exploitation cannot and should not be restored. More than that, he comes to understand, under Rayna’s influence, that the struggle to right the world’s wrongs is his own. He had to find his “place with relation to it,” he wrote on the final page, “in the hope that whatever I did (if indeed I could do anything) would at last integrate the one existence I possessed into the many in which it had been cast.”

Rayna was Rayna Prohme, a globe-trotting revolutionary who Sheean met and became infatuated with in the Communist-led enclave of the Chinese revolution in Hankou. Amidst the White terror unleashed by Chiang Kai-shek, Rayna and Sheean fled to Moscow where they were joined in 1927 by Dorothy Thompson, all of them eager to witness the ten-year anniversary celebrations of the 1917 revolution. On 21 November Rayna suddenly died, whether of encephalitis contracted in China or of a brain tumor remained unclear.

Sheean was devastated. Personal History is amongst other things an extended meditation on the debates he was having with Rayna up to the moment of her death and beyond. Her committed communism was the foil to his individualist search for meaning. Her devotion to revolutionary action stood in contrast to his sense of himself as an observer and chronicler not an actor in history. For Sheean as for Thompson the question was how to achieve meaningful integration.

In the final pages of Personal History, Sheean brings Rayna back to life as his guide, conceding to her the argument they left unfinished in 1927, the anniversary year of the revolution.

“I’m no revolutionary”, he imagines himself protesting. “I can’t remake the machine ..”. To which she replies:

“You don’t have to! All you have to do is to talk sense, and think sense, if you can. … Everybody isn’t born with an obligation to act. … But if you see it straight, that’s the thing: see what’s happening, has happened, will happen – and if you ever manage to do a stroke of work in your life, make it fit in. … if you are in the right place. Find it and stick to it: a solid place, with a view.”

Then, as Sheean imagines Rayna continuing:

“If you want to relate your own life to its time and space, the particular to the general, the part to the whole, the only way you can do it is by understanding the struggle in world terms … to see things as straight as you can and put them into words that won’t falsify them. That’s programme enough for one life, and if you can ever do it, you’ll have acquired the relationship you want between the one life you’ve got and the many of which it’s a part.”

As Sheean concludes:

…. even if I took no part in the direct struggle by which others attempted to hasten the processes that were here seen to be inevitable in human history, I had to recognize its urgency and find my place with relation to it, in the hope that whatever I did … would at least integrate the one existence I possessed into the many in which it had been cast.

Echoing the prose style of its subjects, Deborah Cohen’s Last Call is a compulsively readable work of history and essential contribution to understanding modern America’s relationship to the world.

As she describes her method:

My aim as author has been to follow their own lead as journalists – to convey how it felt to live so exposed to history in the making. When I indicate what a person felt or thought, I am always drawing upon documents to be found in the archives. Their reportorial method was intimate and immediate, and as I worked in their papers, it often felt like walking in on an argument. Even when they were far apart, even after they fell out, they kept right on talking and arguing, long after the actual conversations had ended.

Reading Last Call, I could not help feeling that the conversation that they began continues on to the present day.

For me Last Call reads as a brilliantly illuminating examination of the excitement and the peril of thinking and writing in medias res. How was one to cope with the forces of world history sweeping through the living room, Sheean’s long-suffering wife Dinah Forbes-Robertson was moved to wonder after his breakdown during the Spanish civil war. And as global geopolitics, pandemics, inter-generational stresses, technological change, economic crises, urban crisis, and the renegotiation of gender roles and sexuality continue to upheave our lives, those questions are still with us today.

Read through the lens offered by Deborah Cohen’s Last Call, Sheean, Thompson et al appear as our precursors, our predecessors and our contemporaries in navigating polycrisis.

********

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But it is voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters that sustain the effort. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options: