Did a piece for Foreign Policy on the global economic shockwave from Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

We have had a lot of debate about the way in which the war might trigger a challenge to dollar-hegemony from a new, ruble-yuan nexus – see Chartbooks 94, 106 and 107. I’m unconvinced and impatient with that debate.

In the new FP piece, I argue that it is time to stop worrying about distant Fin-Fi scenarios and to focus instead on the immediate fallout of this shock. The most ugent question right now is how the managers of the dollar system deal with the mounting pressures within that system.

One of the fallacies of the current moment is to imagine that Putin has rudely disrupted an otherwise functional system. In fact, the signs of tension amongst the more fragile low-income and emerging market economies have been mounting for years. And there is little reason, given the recent track record, for struggling low-income and emerging market economies to expect much constructive help.

As I discussed in Shutdown, following the COVID shock of 2020 there was no adequate global response to the debt service problems of the low-income countries. The so-called DSSI initiative was derisory. Rather than debt relief, the main prop for low-income debtors were the falling price of imports and the ultra-low interest rates adopted by the Fed, which unleashed a tidal wave of money looking for yield. Now, energy prices and food prices are rising and so too are interest rates in the dollar zone. Even the normally upbeat Economist has been warming of a “triple whammy”.

As Lee Harris reports in this excellent article in The American Prospect, this combination of pressures has set alarm bells ringing at the UN, World Bank and IMF.

Harris points to a report by the UNCTAD economics team, aptly titled Tapering in a Time of Conflict.

It warns that

For many developing countries, currency devaluation against the dollar is an important driver of inflation: domestic currency depreciation raises the domestic price of imported goods and therefore headline inflation measures. As the Fed and other central banks in developed countries central banks tighten, the currencies of developing countries are likely to devalue further. Policy tightening in the North, in response to supply-side bottlenecks, thus worsens the problem of rising prices in developing countries.

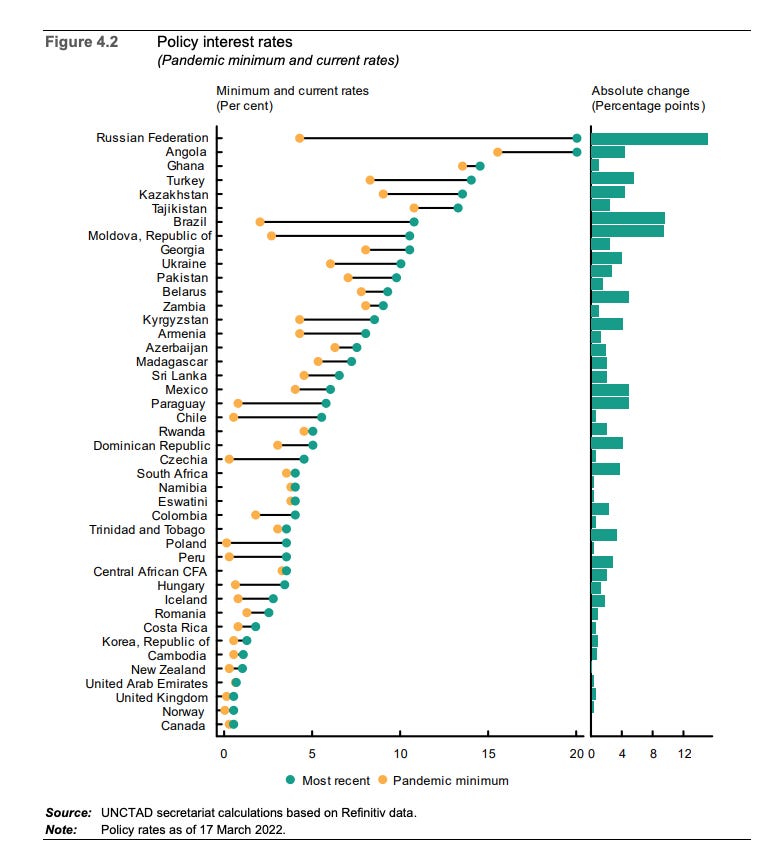

To counter the cycle of devaluation and inflation, EM and low-income markets have respond by sharply raising interest rates, which creates the risk of stagflation. Russia is the extreme case, where the West has induced chaos by deliberate action. But there are some low-income debtors who are not far behind.

Richard Kozul-Wright of UNCTAD is also the co-author with Kevin P. Gallagher of a bold new book making The Case for a New Bretton Woods.

While I am wholly sympathetic to their objectives, I should admit that I have long been a skeptic when it comes to new Bretton Woods proposals. Where is the agency?

Bretton Woods is commonly described as a “postwar conference”. But it was, in fact, convened by tightly coordinated wartime alliance. It met in July 1944 in the interval between the D-Day landings and Operation Bagration in which the Red Army crushed Germany’s position on the Eastern front. There is, mercifully, no equivalent today.

Instead, of the Bretton Woods model, in yesterday’s Foreign Policy article I suggest that a real impulse for action on the part of major financial powers might emerge not from cooperation, or domestic reform, as Gallagher and Kozul-Wright urge, but from great power competition.

Indeed, one might say that we will know whether the narrative of some kind of global competition for financial hegemony is serious, if a concerted response emerges from Europe, the United States or China to the various financial crises around the world.

The looming financial pressure across a large swath of low-income and emerging economies certainly merits a concerted response. In March 2021 Lars Jensen of UNDP published a prescient overview of debt vulnerability. He concluded that

Total debt-service payments at risk (risky-TDS) are estimated at a minimum of $598 billon for the full period covering 2021-2025, of which $311 billion (52%) is owed to private creditors. This year these figures are $130 and $70 billion respectively. For the group of 19 severely vulnerable countries, risky-TDS is $220 billion for the full period and $47 billion this year. LICs account for only 6% ($36.2 billion) of the full period risky-TDS; LMICs account for 49% ($294.1 billion); and UMICs account for 45% ($268.1 billion).

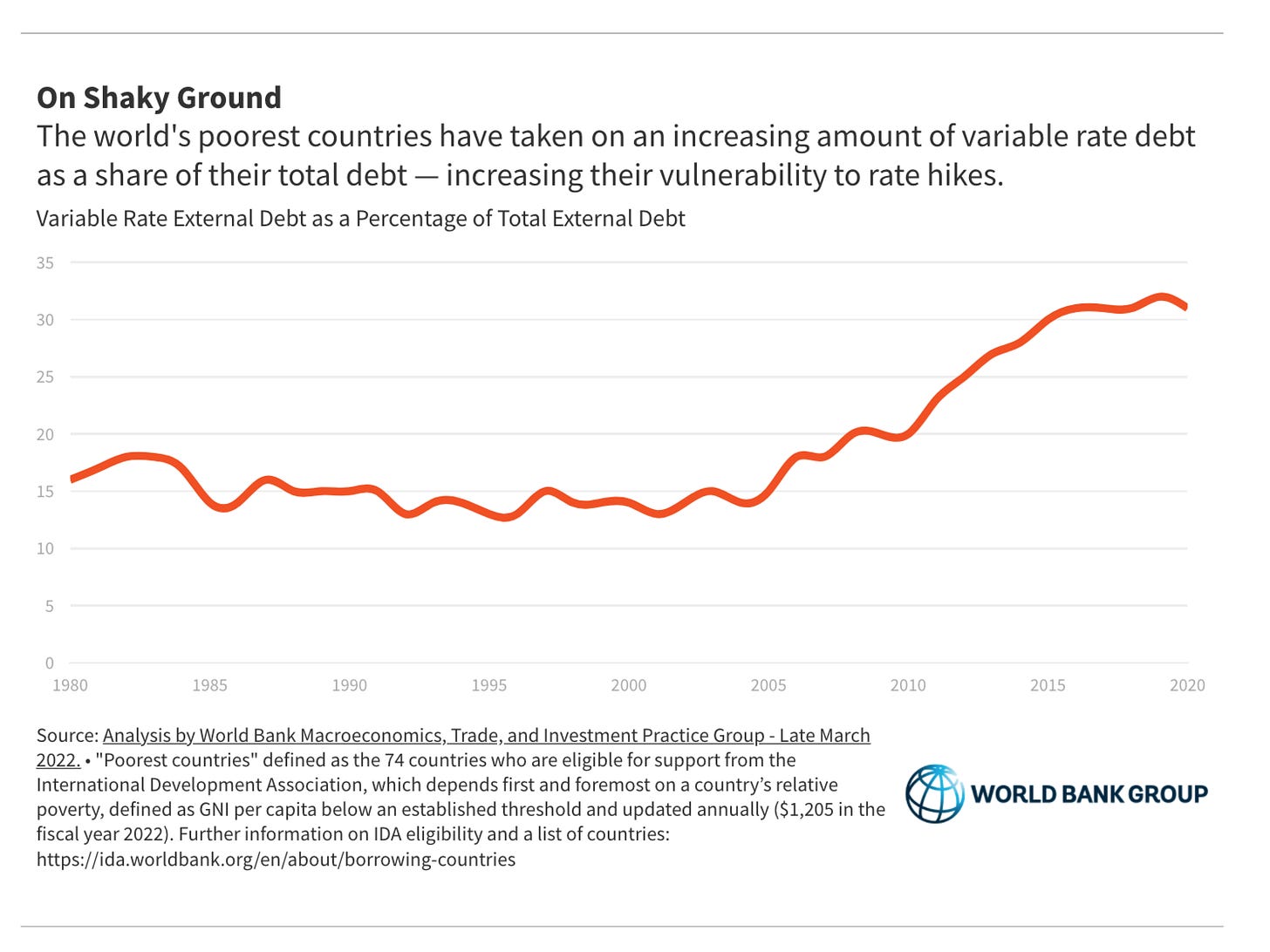

As Marcelleo Estevâo of the World Bank points out, not only is a lot of developing world debt owed to private lenders, thirty percent of poorest country debt is at variable rates (up from 15 percent in 2005) increasing the exposure to Fed rate hikes.

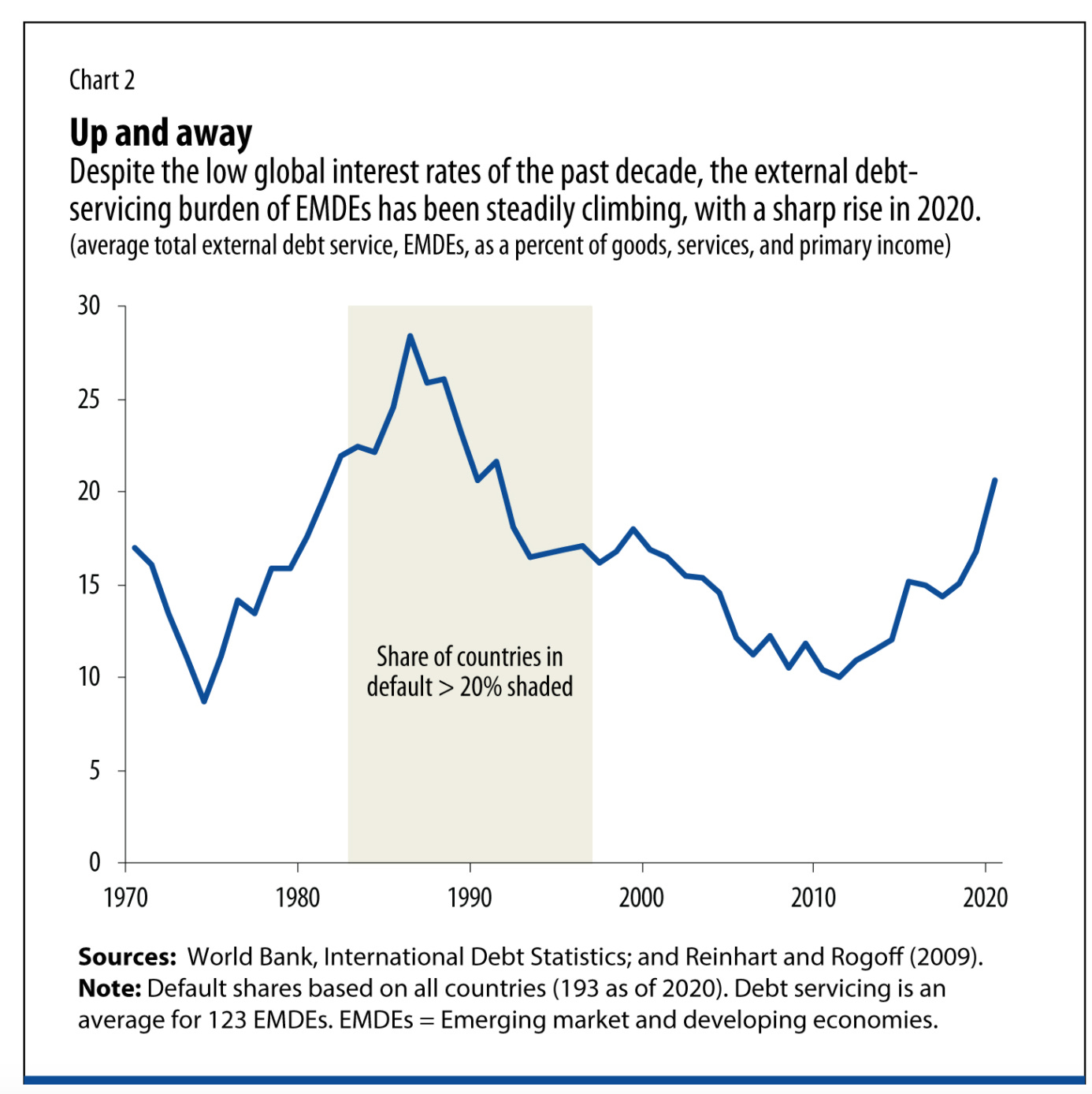

As Ceyla Pazarbasioglu of the IMF and Carmen M. Reinhart of the World Bank point out in an important paper, the debt service burden has been rising ominously.

As they go on to note,

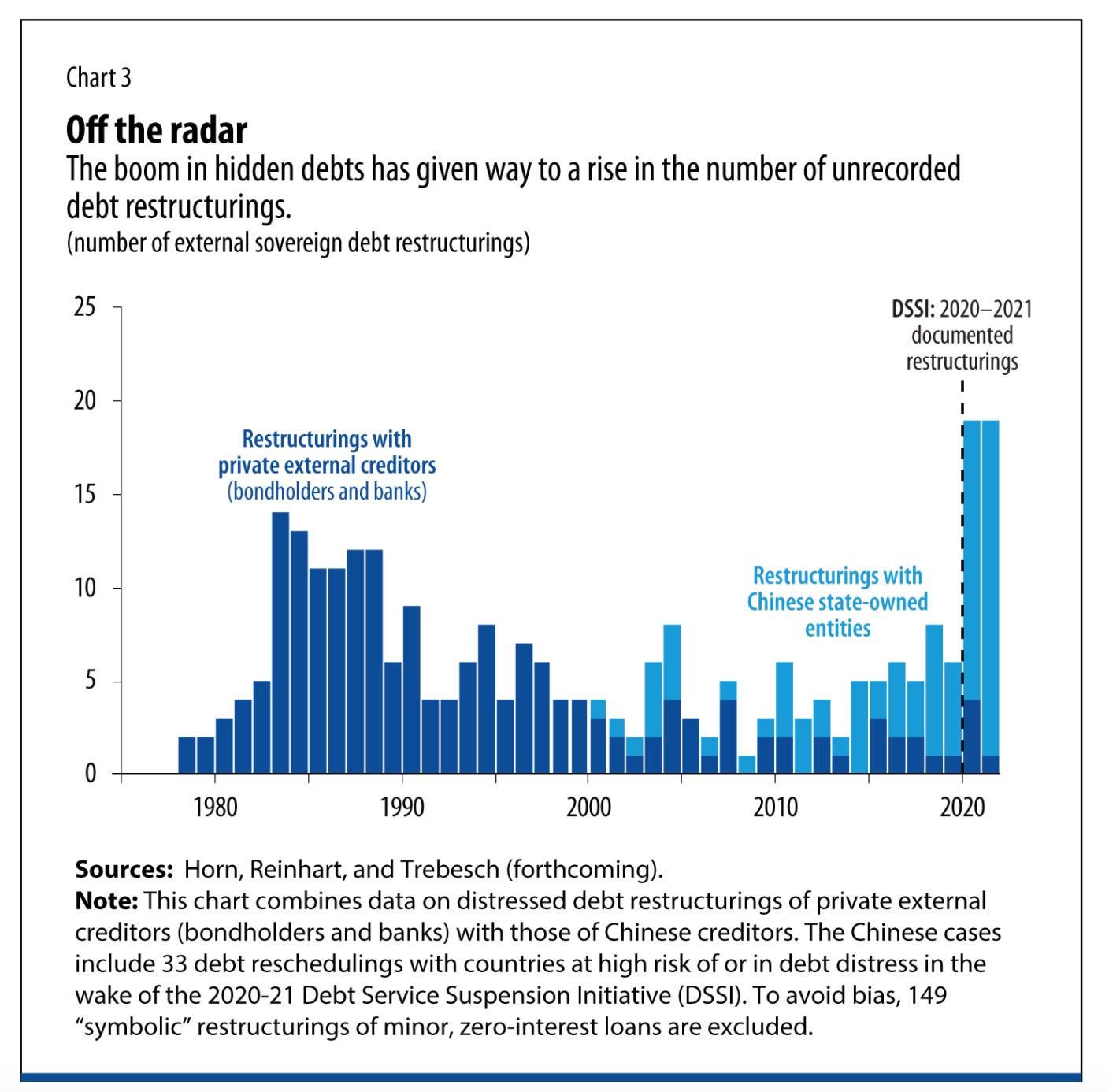

during the period of high global commodity prices and relative prosperity that lasted until about 2014, many emerging market and developing economies looked beyond the Paris Club of official creditors and borrowed heavily from other governments, particularly China. A substantial share of these debts went unrecorded in major databases and remained off the radar of credit-rating firms. External borrowing by state-owned or guaranteed enterprises, which have uneven reporting standards, also escalated. The boom in hidden debts has given way to a rise in unrecorded debt restructuring (Chart 3) and hidden defaults (Horn, Reinhart, and Trebesch, forthcoming). Comparatively little is known about the terms of these debts or their restructuring terms. Historically, opacity derails crisis resolution or, at a minimum, delays it.Restructurings have always started.

Sri Lanka is one place where the mounting pressure of debt has exploded into the open. Sri Lanka is ground zero for the entire narrative of Chinese bare knuckles debt diplomacy. It is of acute interest to India and thus, presumably, to the planners of the Biden administration’s Indopacific strategy. On that score I cannot recommend highly enough The Geometry of Fear in Eurasia co-authored by policytensor (Anusar Farooqui) and Tim Sahay.

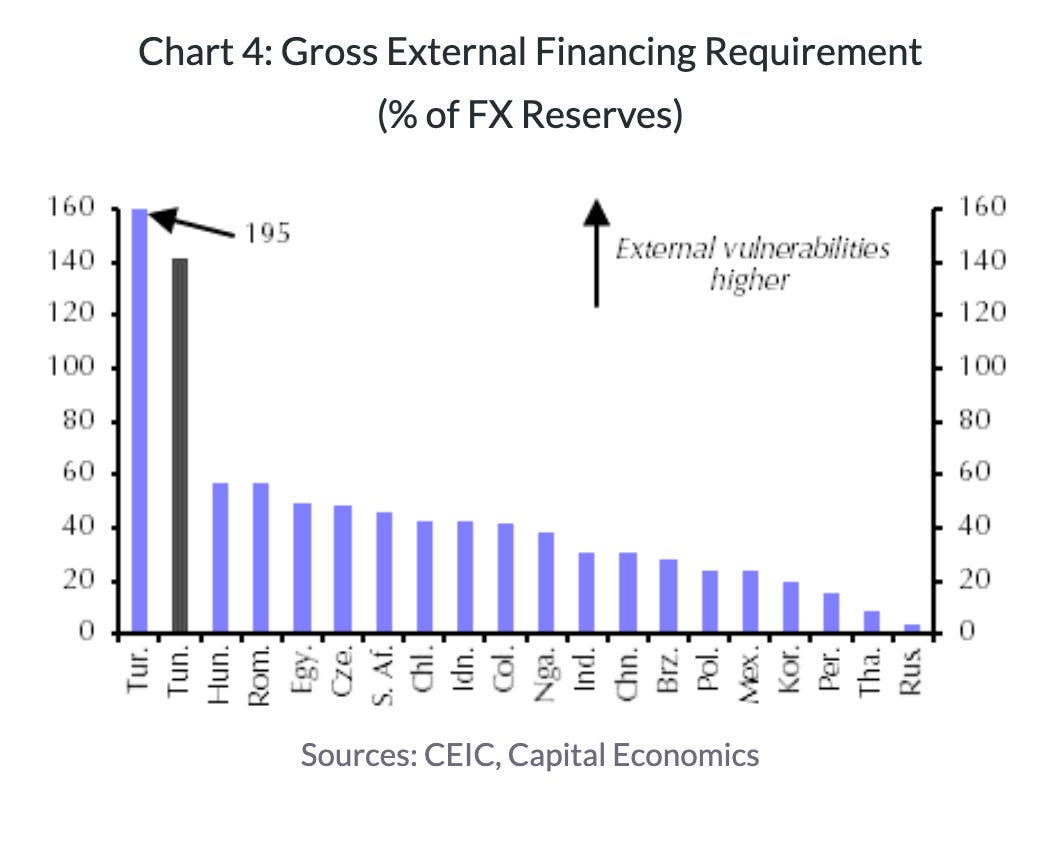

Another flashpoint of financial and political tension that has been gaining attention in Tunisia. As James Swanston of Capital Economics comments:

The current account deficit stands at more than 7% of GDP. And while FX reserves have increased in recent years, they are still low and are insufficient to cover the country’s large gross external financing requirement – that is, the sum of the current account deficit and short-term external debts.

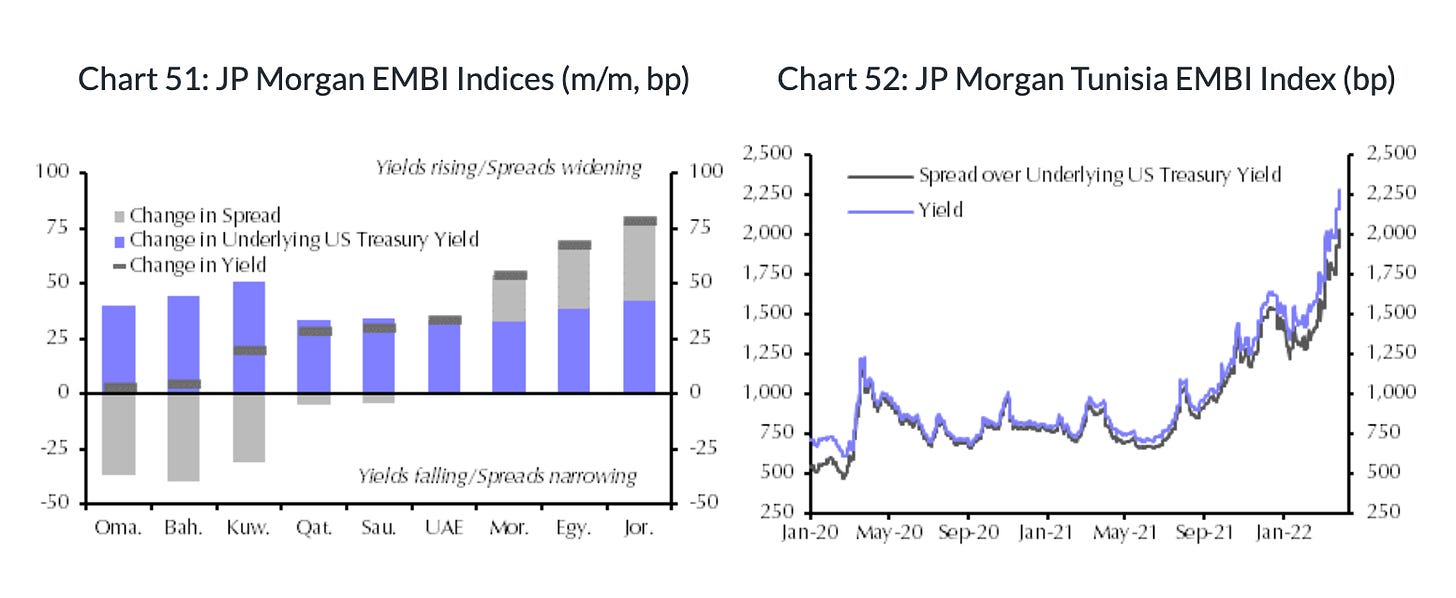

Given its modest resources, Tunisia faces a tough repayment schedule through 2026. Its sovereign dollar bonds have seen spreads widening by a brutal 450bp and yields have surged to record highs near 23 percent.

To describe this situation as unsustainable is an understatement.

Around the region there are many oil and gas exporters, Algeria for instance, which are gaining considerable relief from the commodity price boom. But Egypt, like Tunisia, is coming under severe pressure. It has responded by devaluing the pound by 14 percent since the start of the year. Policymakers are gambling that the gain in export competitiveness outweighs the pain induced by rising import costs and surging price inflation. Egypt’s inflation rose to rose to 8.8% y/y in February – the highest in over two years and interest rates were raised to 9.25%. By the end of 2023 Capital economics expects rates to exceed 11 percent.

It is easy to see how tracing the unorthodox new methods to enable India to pay for Russian fertilizer might get the juices of the Fin-Fi exponents flowing, but in discerning the future of shape of the world economy, the response to these impending debt crises in low-income and emerging market economies will be at least as telling. If there is no response by the United States to Sri Lanka’s mounting crisis, why should we take seriously talk of a new era of geo-economic competition? It wasn’t a good start that Sri Lanka was not even invited to the “Summit of Democracies” in December. As Mihir Sharma pointed out at the time, “countries like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka — flawed democracies that are being wooed by the People’s Republic with money and flattery — are precisely the countries you want in the room.”

Likewise, the EU urgently needs to concert its response to the situation in Tunisia. It is a good sign that at the end of March Brussels committed 450 million euros in aid to support the Tunisian budget.

This is not to appeal for some neocolonial burden of stewardship. In neither case can the crisis be “solved” from the outside. And as Youssef Cherif spells out in this Carnegie Brief on the EU’s Tunisia policy, the choices involved are complex and divide the EU members. But insofar as external creditors are involved, the great powers have an indispensable role to play. To pretend to neutrality, as we now like to say, is either naive or cynical.