| Adam ToozeMar 1 | 447 |

Gustave Doré L’Énigme, 1871

As Russian forces begin to resort to heavy artillery “fires” in their assault on Kharkiv, the character of the war in Ukraine may be about to take a terrible turn.

Except for heavy shelling around Kharkiv, use of fires have been limited compared to how the Russian mil typically operates. Sadly, I think this will change. Russian mil is an artillery army first, and it has used a fraction of its available fires in this war thus far. /16

— Michael Kofman (@KofmanMichael) February 28, 2022

In the days ahead, it is to be feared that the almost carnivalesque sense of the war as a people’s uprising against a clumsy, incompetent and oppressive enemy, will give way to something much grimmer. And that begs the question, how are we to locate this conflict in recent military history?

Is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as so often claimed, the first “big” war (in Europe) since 1945?

Clearly not. The obvious counter example to point to is Yugoslavia (1991-2001).

We tend to think of Yugoslavia in terms of atrocity and siege, or in terms of NATO intervention etc. All for good reason.

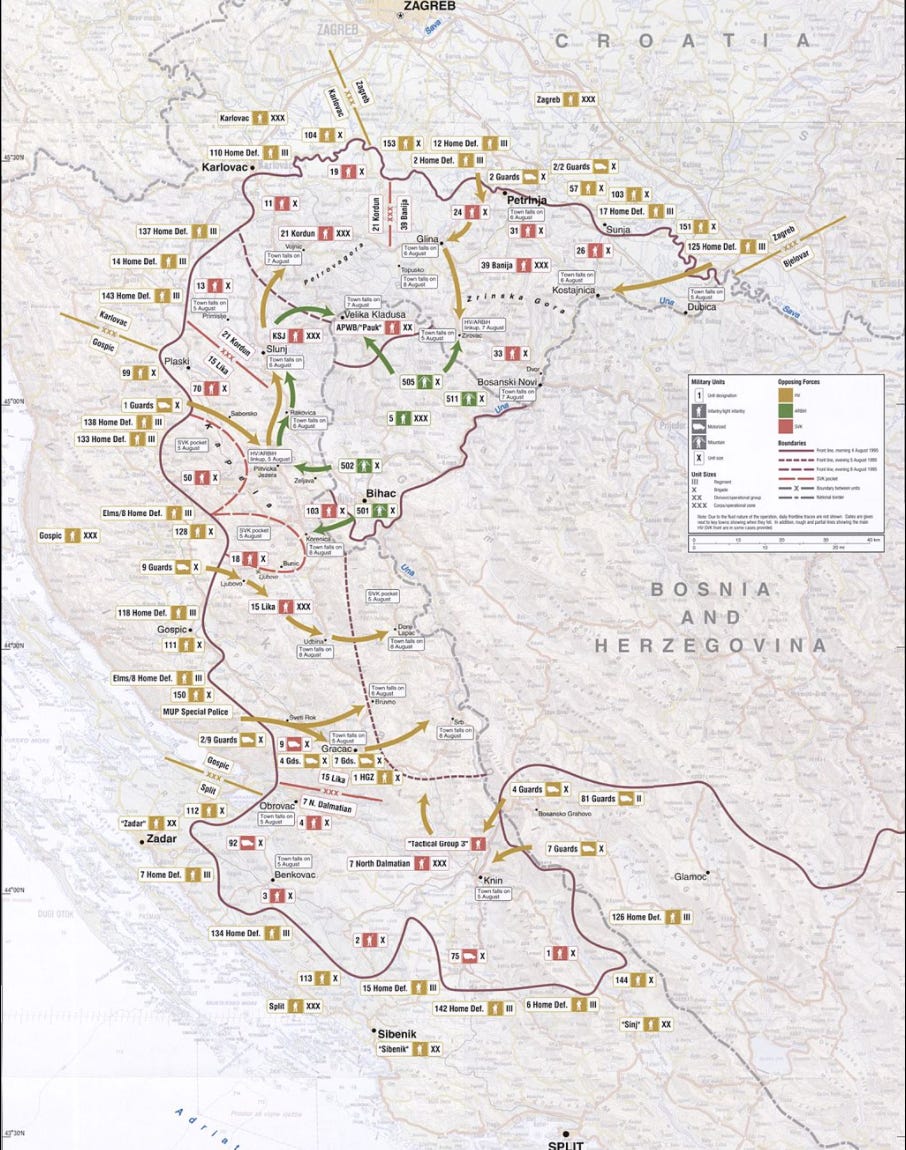

But, in some of its many phases, the war in Yugoslavia took on the form of more large-scale mobile operations, very akin to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Operation Storm unleashed by the Croat Army in the summer of 1995 was particularly dramatic. It was, at the time, the largest battle fought in Europe since World War II. Total troop strength on the Croat side came to 130,000 attacking on a 630 km frontline.

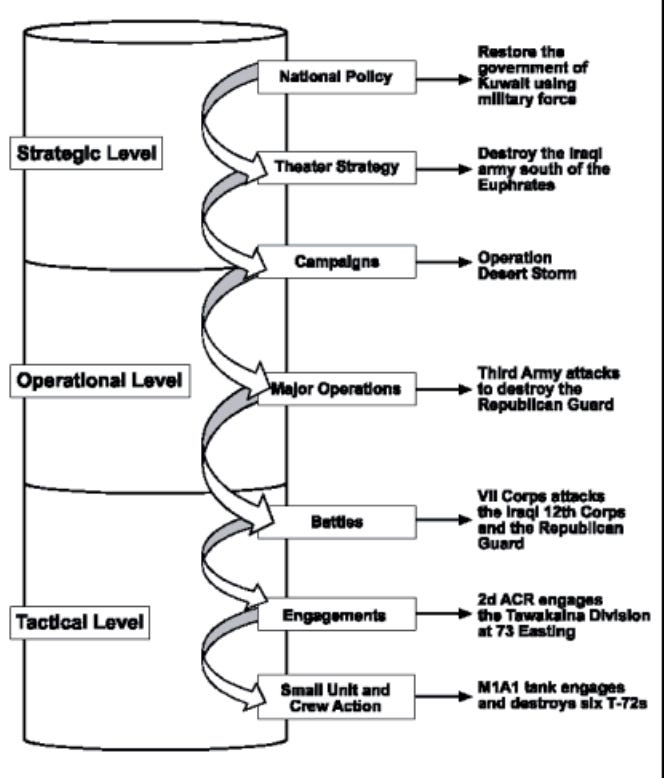

Operation Storm was war waged at what is called the “operational level” i.e. at the level of a campaign consisting of multiple interlocking battles. The Croatian army maneuvered at Corps level, i.e. in units of 30,000 men. So far you would have to say that it was vastly more coherent and effective than the Russian campaign against Ukraine.

Source: FM-3

But why restrict yourself to Europe?

For sheer scale and lethality nothing in recent history compares to the conflict in Central Africa in the 1990s and 2000s which claimed millions of lives.

But think also of the Eritrean-Ethiopian war between 1998 and 2000, which involved armies of more than a hundred thousand and well-over a hundred thousand killed in combat.

If we limit ourselves to Eurasia, we would need to consider Kuwait, Chechnya, Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria.

In Iraq the US and its allies deployed a force of 250,000 with far heavier preparatory bombardment by aerial forces – remember “shock and awe”. Their progress in the early stages was similarly slow.

Russia's advance has been extraordinarily rapid. For comparison's sake, here are same-scale maps of 48 hours into the US invasion of Iraq and @JulianRoepcke's estimate after 36 hours in Ukraine.

— The Bazaar of War (@bazaarofwar) February 26, 2022

Anyone saying Russia is bogged down is nuts. https://t.co/X4iVuIW1Ei pic.twitter.com/U6pbpyvx8u

This animation gives an impression of how a large-scale military offensive can unfold slowly at first and then very rapidly.

For the full picture, here's the full 26 days of the Iraq invasion. pic.twitter.com/DKdzjpouEk

— The Bazaar of War (@bazaarofwar) February 26, 2022

This is NOT to say that the Russian offensive in Ukraine will follow the same pattern. But it is to warn against drawing premature conclusions from the first days of a campaign. Its logic may unfold only over time.

In the murderous campaign in Chechnya in 1999, Putin deployed a force of about 80,000 Russian troops. In the punitive expedition in Georgia in 2008, Russia deployed about 70,000 troops. Ukraine involves a force twice that size.

As one observer remarks, the last time we saw heavy Russian Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRS) in use prior to Kharkiv was in Syria in 2018.

What appears to be a very clear cluster munition strike. Haven’t seen this kind of footage since the siege of Douma in 2018. https://t.co/rFCSxcBNhm

— Nick Waters (@N_Waters89) March 1, 2022

It is striking that in Ukraine these horribly imprecise, terrifying and devastating weapons have been employed sparingly so far. Back to the legendary BM-13 Katyushathey have been seen a staple of the Russian way of war.

Medium-sized wars

In any case, the post-Cold War period is not one characterized only by small-scale irregular conflict, fundamentalist insurgencies and the like. It has been punctuated by the explosion of wars involving substantial contingents of regular troops numbering between 50 and 200,000 strong.

It has been an era of “medium-sized wars” – forgive the phrase.

Size matters because it tells us something about the parties to the conflict and the relative scale of their commitment. What we have not seen since 1989 is anything like total war waged by any of the countries that might be considered major powers. Smaller and poorer states have waged something akin to total war. None of the G20 has.

For Russia and the United States, the size of the wars they have been involved in allows the conflicts to be defined as acts of policing, for the purpose of eliminating WMD, regime change, disarmament or “denazification”.

The justification may or may not be plausible. But the fact that the war can be carried by limited numbers of troops means that the rationale for the war does not need to be put to the test of broader public opinion. These are “wars of choice”.

This term is usually applied to the decision-makers. But the idea of a war of choice also extends to the home front.

As a civilian in one of the large states involved in a war of choice, you do not have to be involved. It is a matter of political conviction, career or lifestyle. Very different, of course, for those in the country made into the battlefield, whether it be Iraq, Afghanistan or, now, Ukraine. They are subject to all-encompassing and annihilating destruction, as Grozny was in 1999-2000 and Kharkiv and Kiev may be soon.

What did Russia spend in Syria?

In recent decades, Russia has been involved in at least three of these limited, “medium-sized” conflicts – Chechnya, Syria, and now Ukraine. This is not to mention its military engagements in Abkhazia, Transnistria, North Ossetia, Tajikistan, Dagestan and Georgia.

For its involvement in Syria, thanks to the liberal opposition in Russia, we have particularly detailed estimates of the cost, allowing us to gauge quite precisely the extent and the limits of the commitment.

The intervention in Syria through which Russia rescued the Assad regime cost Moscow at its height about a billion dollars per year (at exchange rates prevailing in January 2021). One can itemize the cost down to individual intervention. Air strikes per sorti by a Russian aircraft are costed about $75k. A cruise missile strike is closer to $1m. Families of Russian soldiers killed in Syria received the equivalent of $40k each.

To put this in perspective, all told according to one very useful summary by Nikola Mikovic of work by Novaya Gazeta

over the past 20 years the Kremlin spent $609 on geopolitics, including $224 billion for various energy projects, $270 billion to support its former and present client states, as well as $116 billion for debt relief. Critics could argue that it is nothing compared to what the US, the European Union and the United Kingdom have spent attempting to maintain the narrative of being global powers. However, unlike modern Russia, the Western powers are known for investing money in wars and regime changes, but at the end they almost always benefit from such operations.

According to Novaya Gazeta’s analysis, Ukraine has always been a key priority of Putin’s geopolitical spending.

Russia, on the other hand, invested at least $39 in Ukraine until 2014, according to Novaya Gazeta analysis, including $3 billion loan that Kiev openly refuses to pay back. Since the former Soviet republic effectively stopped being in Russia’s sphere of influence after the Maidan events, the Kremlin has no mechanism to force Ukraine to make a repayment.

Russia’s “investment” in Ukraine came in the form of loans and energy subsidies to Ukraine. It is grotesque to bring this up at this moment, but it shapes Russia’s contemptuous view of Ukraine as an ungrateful and unreliable puppet state.

It also helps to put in context, Russia’s engagement in supporting the breakaway Donetsk and Luhansk regions in Ukraine. In 2021, it was estimated that they were costing Moscow c. $6 billion per annum.

The long struggle in Ukraine

Pointing to that backdrop is crucial, because it is clearly misleading to think of the battle in Ukraine as starting last week. This was the point made repeatedly by Ukraine’s government over the last twelve months.

The war we are witnessing is not a “war scare” gone wrong but a spectacularly violent escalation of a long war of attrition. Ukraine has been involved in a shooting conflict with Russia since 2014 and in that conflict, whether the West recognized it or not, both Russia and the Ukrainians themselves, saw Ukraine as a proxy of the West.

On this count I found this Vice film from the frontline in Ukraine with commentary by Matthew Rojansky very compelling.

Similarly stark is the warning by Fiona Hill in this Politico interview.

We are already in a hot war over Ukraine, which started in 2014. People shouldn’t delude themselves into thinking that we’re just on the brink of something. We’ve been well and truly in it for quite a long period of time.

How did Ukraine’s military get so competent?

Which begs the question, how did Ukraine’s military become capable of withstanding the kind of assault we have seen so far?

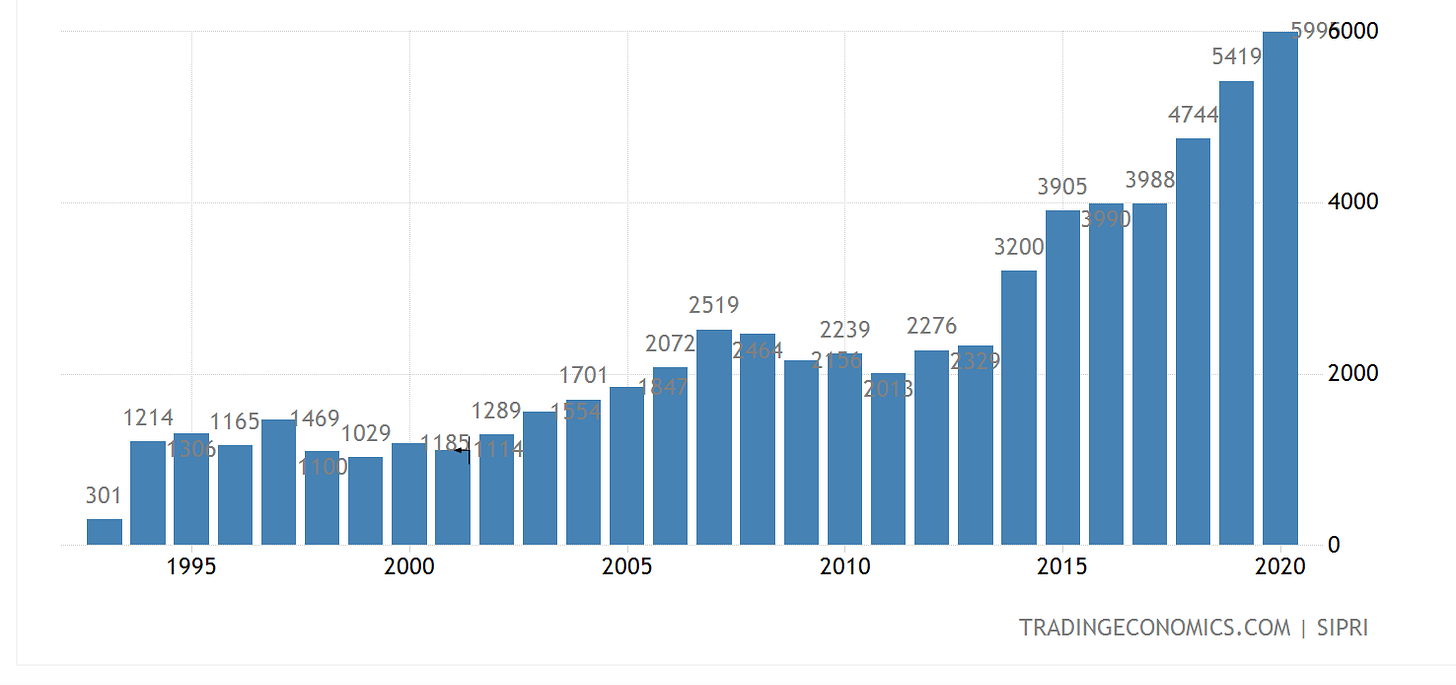

One simple way to index Ukraine’s defense effort is to look at military spending which has surged since 2014.

Source: Trading Economics

A law passed in 2018 requires Ukraine to spend at least 5 percent of GDP on security service. As the Congressional Research Service points out, it generally falls short. It also gives a figure of only $4 billion for budget spending in 2021. This is lower than that give by Trading Economics, but presumably this depends on exchange rates and it does not change the general conclusion of a large increase in spending since 2014.

That surge is also reflected in troop strength.

In 2014, Ukraine’s defense minister said the country had 6,000 combat-ready troops. Today, Ukraine’s army numbers around 145,000-150,000 troops and has significantly improved its capabilities, personnel, and readiness.

The overall strength of the armed forces comes to 200-250,000 troops.

Credit for this expansion must be given to President Poroshenko who despite involvement in corruption, or perhaps because of it, saw the military as a key area of state spending. It is not for nothing that he has now appeared on TV touting a Kalashnikov and claiming that it is the army “he made” that is winning the war.

Thanks to the brutal fighting against the separatists in the East, it is an army whose ranks include many with real combat experience. By 2017 Ukraine had suffered 10,00 casualties in the East.

What did NATO provide?

Already in the 1990s Ukraine was a partner of NATO and since 2014 those relationships have tightened. In 2016, NATO endorsed a Comprehensive Assistance Package (CAP) for Ukraine “to implement security and defense sector reforms according to NATO standards.” In June 2020, Ukraine became one of NATO’s Enhanced Opportunity Partners, a cooperative status currently granted to six of NATO’s close strategic partners.

NATO members provide training to and conduct joint exercises with the Ukrainian armed forces in a multinational framework.

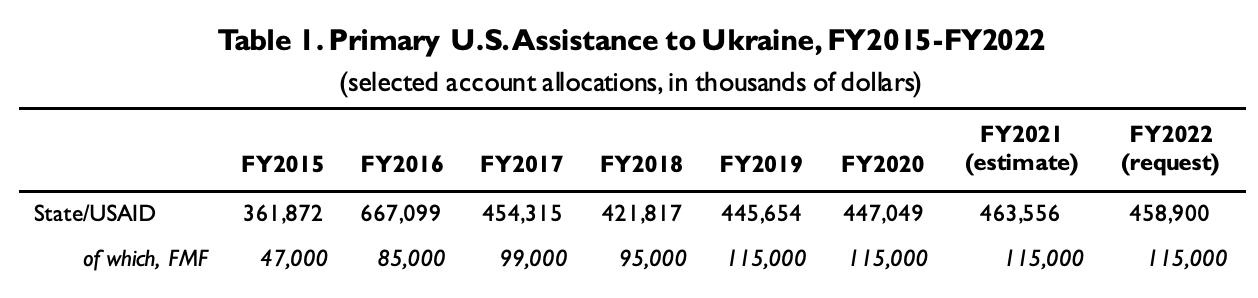

From FY2015 to FY2020, State Department and USAID bilateral aid allocations to Ukraine totaled about $418 million a year on average, of which Foreign Military Financing has recently accounted for $115 million.

Source: FAS

The Department of Defense’s Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative has recently added another $275 million for a total of about $400 million, or one tenth of Ukraine’s overall annual military spending.

In all, the Congressional Research Service estimated in October 2021 that the United States has allocated more than $2.5 billion in security assistance to Ukraine since Russia’s 2014 invasion.

From 2017 to 2021, security assistance has included not just training but assistance to

enhance the lethality, command and control, and situational awareness of Ukraine’s forces through the provision of counter-artillery radars, counter-unmanned aerial systems, secure communications gear, electronic warfare and military medical evacuation equipment, and training and equipment to improve the operational safety and capacity of Ukrainian Air Force bases.169 In 2018 and 2019, DOD notified Congress of two Foreign Military Sales to Ukraine for a total of 360 Javelin portable anti-tank missiles, as well as launchers, associated equipment, and training.170 According to media reports, these missiles were to be stored away from the frontline.171 In September 2021, the Biden Administration announced plans to provide “a new $60 million package for additional Javelin anti-armor systems and other defensive lethal and nonlethal capabilities.” 17

Famously, President Trump’s “negotiations” with his Ukrainian counterpart over the release of the 2019/2020 tranche of military aid would form a major part of his Congressional impeachment.

The US is not the only NATO partner to have been involved in training Ukrainian forces. The UK has since 2014 established Operation Orbital to support the Ukraine. And as is captured in the Vice video, there is also a US/Canada/UK/Ukraine Joint Commission for Defence Reform and Security Cooperation which was established in July 2014.

Can this smattering of aid have made the difference? It seems unlikely. As this report by David Axe of Forbes points out, though Western deliveries of Javelin’ anti tank missiles grab the headlines, the workhorse anti tank weapons of Ukraine’s army are relatively affordable ($20,000 per shot) Stugna-P rockets, manufactured in Ukraine, which have proven their worth in combat in the Donbass.

Are the Russians really as incompetent and unmotivated as our admittedly one-sided media feeds makes it seem?

It is very hard to tell at this stage. We can only rely on the best available Western expertise.

For my money the two indispensable follows on the US side, no disrespect to everyone else, are Michael Kofman and Rob Lee, both tagged in this tweet:

It’s clear from a spate of POW interviews I’ve seen the troops themselves had no idea they were going to launch this op and were completely unprepared for it, including officers. Morale is low, nothing was organized, soldiers don’t want to fight & readily abandon kit. https://t.co/hPtJGrZnR2

— Michael Kofman (@KofmanMichael) March 1, 2022

In light of their judgements, perhaps we should be less surprised than we are that Russia is bogged down and is increasingly forced to resort to massive firepower.

An analysis of the fighting in the Donbass in 2014 and 2015 by Nic Fiore of the US army highlights several fights in which Ukraine forces showed their ability to overcome the supposed material of superiority of Russian Battalion Tactical Groups.

The Clausewitzian triangle

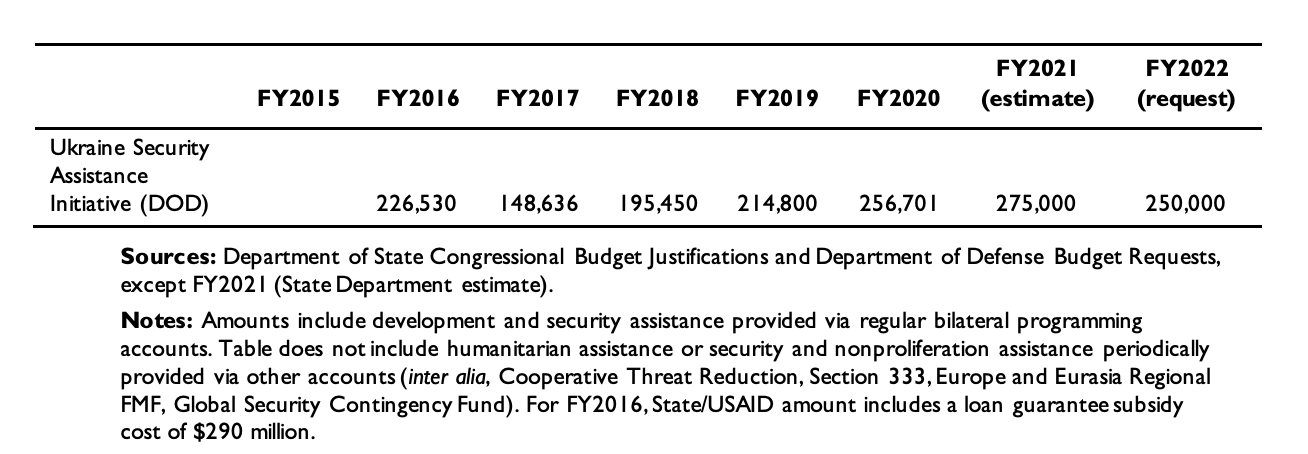

In watching the horrifying escalation over the weekend I could not stop thinking about the Clausewitzian triangle, which I had been lecturing about the previous week in my course on War in Germany.

I use a slide like this in a lecture about the Franco-Prussian war and the escalation that occurred in that war AFTER the defeat of the regular French army at Sedan on September 1-2 1870. There followed the franc tireurs conflict, the gruelling siege of Paris, the Commune, the punitive peace of Frankfurt.

The horrifying analogy to the current moment is that in seeking to end the war as quickly as possible, to avoid the further escalation of nationalist passions on both sides (which would make both definitive victory and peace elusive) and to forestall the possibility of wider international entanglement, the Prussians fell to arguing over how to apply greater pressure to the French government. The decision was to besiege and bombard Paris.

You get a sense of the argument here.

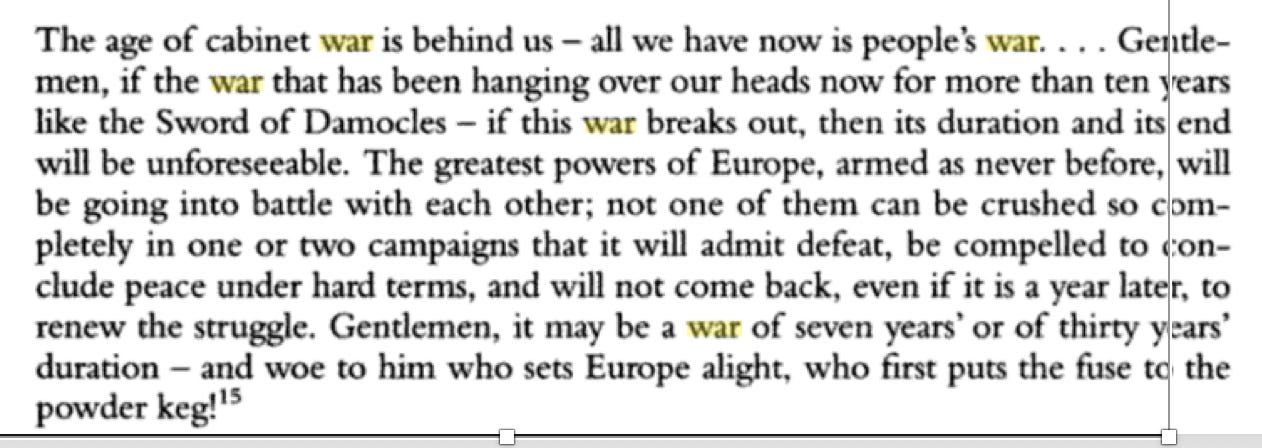

The lesson of that famously victorious war was summarized decades later in his final speech of the Reichstag by Chief of Staff Moltke on 14 May 1890: