… or to wartime Keynesianism?

Sanctions are the chosen weapon of the West against Putin’s aggression.

Rather than starting small we have gone immediately to an attack on the central bank.

In response, the Russian central bank has effectively stopped capital flows our of Russia and nationalized foreign exchange earnings of major exporters. It now requires Russian firms to convert 80 percent of the dollar and euro earnings into rouble. This helps to bolster the rouble’s value and provides a flow of foreign exchange into the country.

The “well-respected” i.e. highly conservative leadership of the Bank of Russia immediately raised rates and adopted the full array of central bank interventions that one might expect, pumping liquidity into the banking system and easing capital requirements. Reading the central bank’s website is a surreal experience – post-2008 style “macroprudential buffers” in the service of stabilizing Putin’s home front.

The question now, is how severe do we expect the impact of sanctions to be. How rapidly will they act? How will they impact Russian society and how might they change it politics?

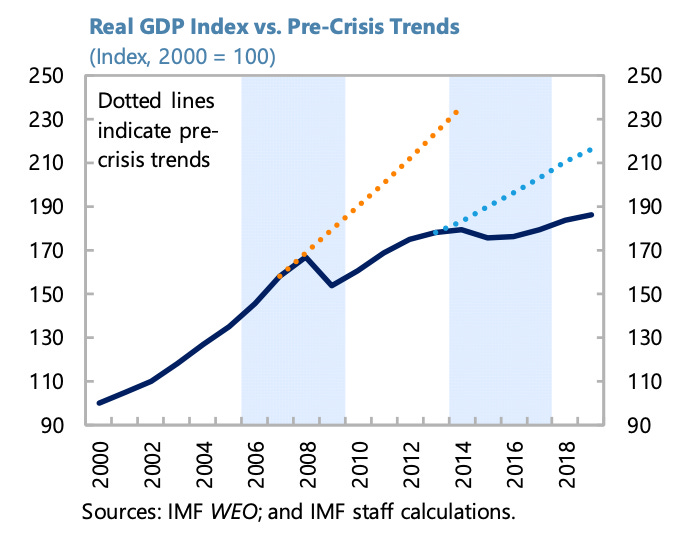

It is tempting to think about this in terms of the effects on exports, efficiency, long-term damage to economic growth etc. The outlook for Russia is surely grim. The sanctions will further worsen a growth-rate which, since Crimea, has already been depressed.

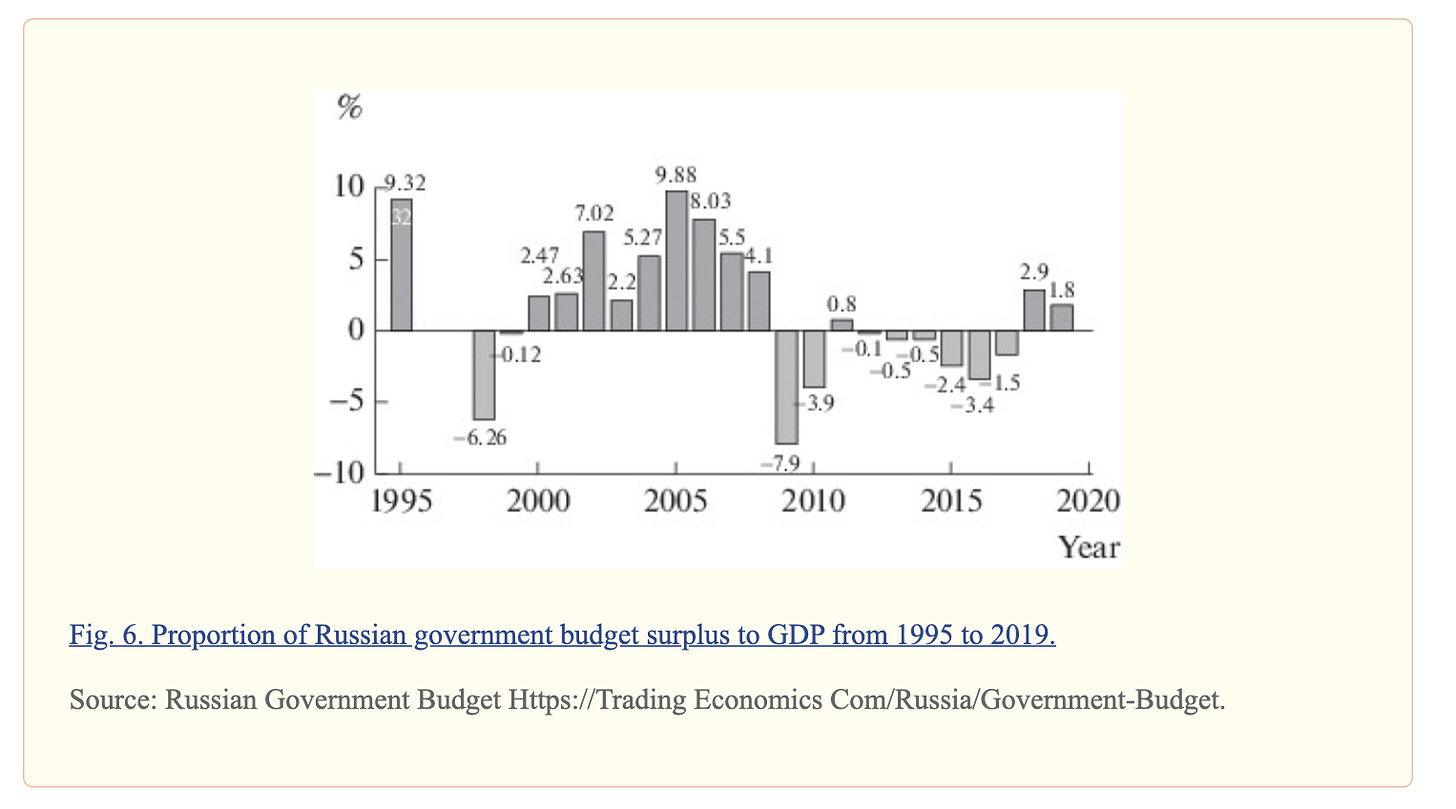

But why is Russia’s growth so poor? No doubt, sanctions, corruption, state-domination of the economy, all play a role. But, a factor that we too often neglect, is self-imposed – the draconian tightening of fiscal policy since 2016.

How rapidly would we expect a modern economy to have grown with a government budget shifting from a deficit of 3.4 percent of gdp to a surplus of 2.9 percent in a matter of three years?

Under Finance Minister Siluanov, Russia pursued a regime of severe austerity, coupled with the a free floating exchange rate and an increasing shift to a domestic bond market – the classic trifecta of the Wall Street consensus (Daniela Gabor).

By 2017 even Alexei Kudrin, the legendarily hawkish finance minister of Putin’s first decade, complained that the new regime proposed by his successor seemed “excessively severe”.

This is more than merely a point about macroeconomics.

It was commonly observed that Putin’s regime manifests a striking tension between its aggressive sovereignty and its immersion in the world economy. What is less frequently commented on is the tension between Putin regime’s “state capitalism”, which might be taken to imply freedom of action, and its rigid adherence to conservative fiscal and monetary norms. Putin is no Erdogan.

It is tempting to read the latter as the condition of the former i.e. the price for the smooth insertion of Putin’s regime into the regime of globalization – despite its aggressive diplomatic and military challenge to US hegemony – was Russia’s peerless orthodoxy in monetary and fiscal policy. If this is the case, in the current situation of open confrontation with the West should we expect Russia’s conservative economic policy regime to survive? If it does not, if Moscow puts its war economy on a Keynesian footing, what are the implications for the effectiveness of sanctions?

Already in the wake of the Crimean annexation and subsequent sanctions, Russia’s domestic policy regime was coming under internal pressure. After several years of stagnating real incomes, Russia’s economic policy elite began seriously to worry about economic growth. The new government of January 2020 came in with a growth mandate.

As Vladimir Mau, Rector of RANEPA, described the situation, in a fascinating articlepublished in 2020:

The formation of the new Russian government in January 2020, was a reflection of the society’s predominant desire to accelerate economic development. … Mikhail Mishustin’s government presented an economic transformation plan which included a set of financial, institutional and structural measures based on the national goals and national projects which the Russian President established in May 2018 …

This was a break with recent history. Hitherto, as Mau points out, Russia monetary and fiscal policy had been set without regard to the business-cycle or growth, with a focus above all on inflation and fiscal solidity. The experience of bankruptcy and inflation in the 1990s were formative. So too was the fact of Russia’s institutional weakness and the need to harden the economy against geopolitical pressures.

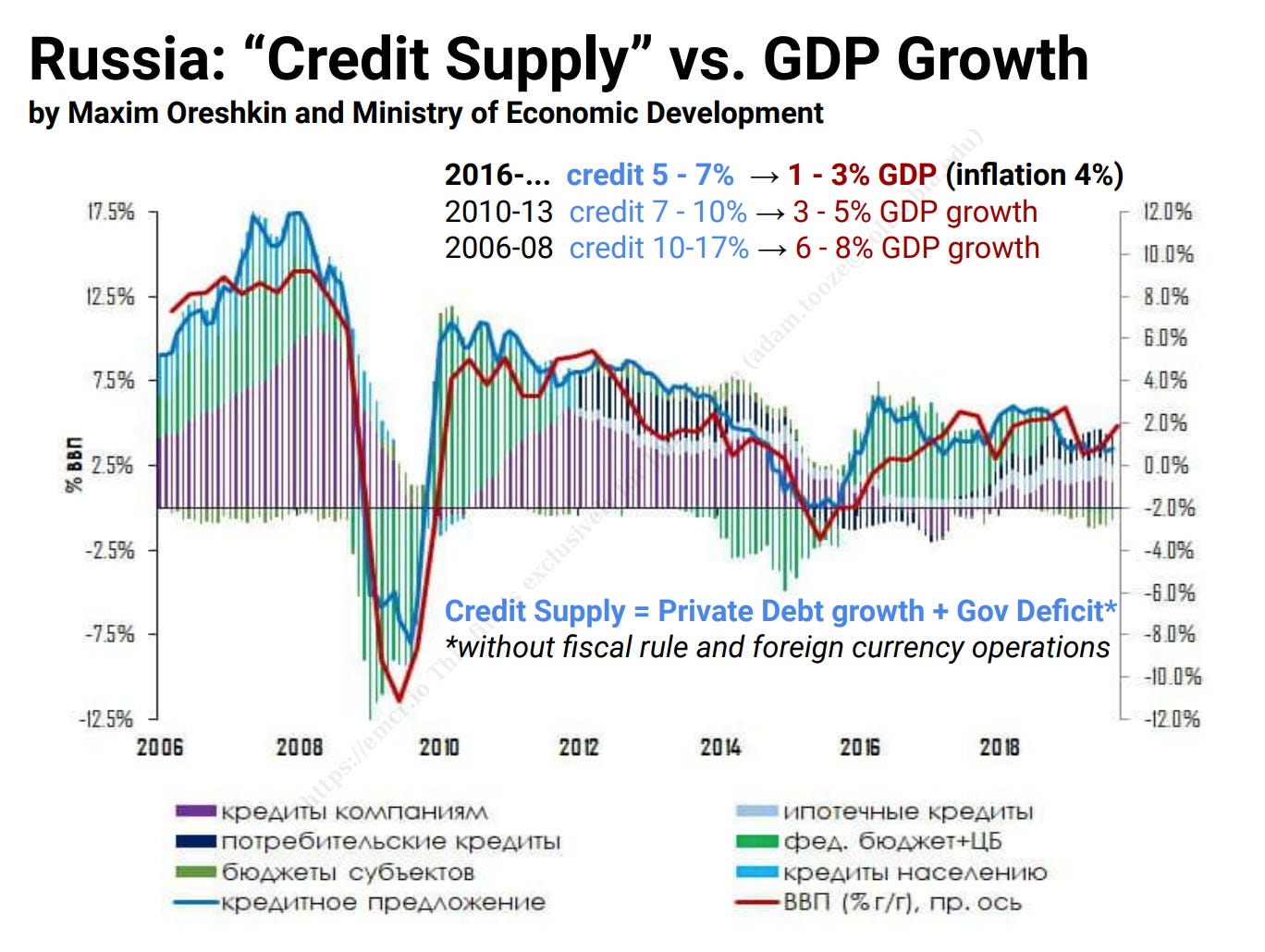

However, with all these caveats and reservations, (Mau commented in 2020), it looks like the government needs to gradually move towards a more flexible fiscal and monetary policy that would take cyclic fluctuations into account that are characteristic of a market economy. This was reflected in discussions during 2019 and 2020, concerning economic growth and the reasons it was slowing down. While institutional issues are indeed important, recent discussions on growth-related issues are increasingly focused on macroeconomic factors, primarily on supply and demand, i.e. on the sources of funding for the growth

As a result, growth acceleration was viewed mainly through the lens of fiscal stimuli and consumer lending from 2018 to 2020. National projects were to become the primary channel for the measures in question. Moreover, with inflation dropping below the 4% target and the budget in surplus, some room was left to maneuver. The issue of managing aggregate demand became highly relevant within economic policy. This was reflected in the key topics of economic discussions. These include, first of all, the nature and volume of fiscal demand.

In looking for sources to activate aggregate demand within the country, some Russian economists and politicians turned to the Modern Monetary Theory. …. Russia does not have heavy national debt and budget deficit problems. On the other hand, the ruble, though a sovereign currency, is not a global payment instrument, and economic growth is still weak. In this context, the applicability of MMT first of all means active engagement by the monetary authority to improve aggregate demand, which effectively translates to the Central Bank performing its function as an “institute for development.” This raises the issue of the Central Bank’s independent status. This problem was first raised in 2019, but the intensity of the discussion is likely to grow—not just within Russia but in other developed economies as well.

MMT in Moscow!

For some more glimpses of the debate going on in Russian economic policy at the time, check out this twitter thread

Aside of #MMT debate btw Galbraith and Rogoff @GaidarForum2020, there is another interesting event taking place in #Russia.

— Alexander Valchyshen (@AlexValchyshen) January 15, 2020

This is an appointment of new prime minister of Russian government Mikhail #Mishustin.

And this thread is my understanding of the development.

1/

The debate seems to have been kicked off by explosive interview given in October 2019 by the youthful Maxim Oreshkin, who we was then serving as Economy Minister.

As far as modern monetary theory MMT is concerned that around this history there are now many myths, there are many different speakers and all of them are trying to talk about it… but I am may be… I am, too, of cause acquainted with it. Then, what I would turn my attention to, what it seems to me correct, that colleagues says that, in reality, between private and state credit, between budget deficit and bank credit there is no big difference, in fact. And there are no, for example, such terms as equilibrium deficit of state budget or equilibrium interest rate. And that all these are determined by adequacy or in-adequacy of level of aggregate demand in the economy. And that main limit/constraint on demand is the level of price inflation. Because when inflation starts rising this in truth demonstrate that there is excess demand in the economy. Balance between budget deficit and private credit should be found from the point of view of those goals of socio-economic development that exist. And here the balance could be different for a certain country. In some countries, it may be big deficit [of gov’t budget] and there is nothing scary out of it. [Even] there is a rising public debt. If goals not connected to the rise of private credit but connected to the rise of state credit and there are no constraints to a country that has own currency [money unit of account], borrows in own currency from the point of view of [gov’t] deficit and [public] debt.

…

(Time 26:40) Question: The next question. I do not know whether Economy Minister will talk about the monetary policy. But, nevertheless I am to ask you this question. You are regularly criticizing the [Russia’s] central bank for the excessively tight stance of monetary policy…

Answer: …I will answer you right away by saying that… no, I do not do criticize [as you said] on a regular basis.

As is clear from the interview, the question of the independence of the central bank immediately arose. And the question was pointed: How could the central bank’s extremely conservative approach to inflation-control be reconciled with aspirations to more rapid growth?

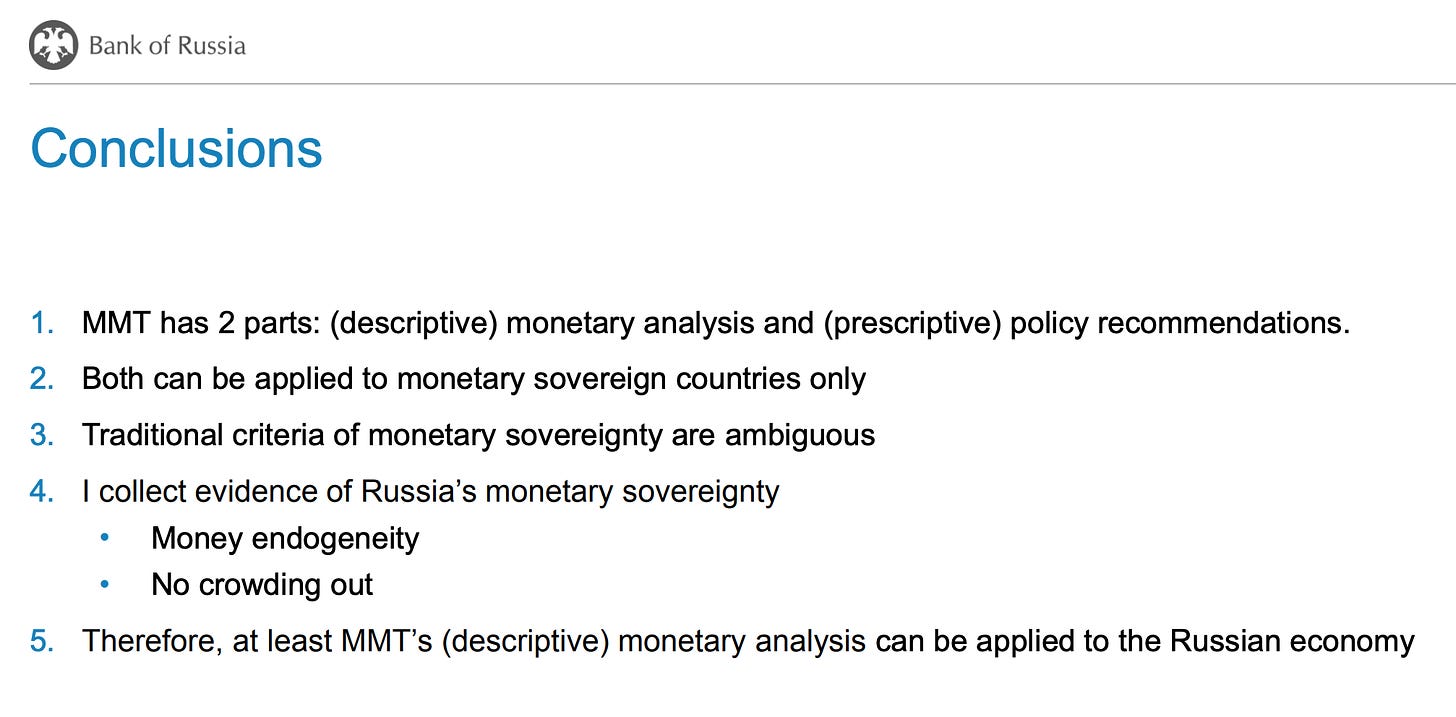

Following Mau’s lead, I have been able to find two papers dealing with MMT in the Russian context. One of them, by Vadim O Grishchenko, comes from inside Russia’s central bank.

Grishchenko focuses not on MMT’s policy prescriptions, but its description of the operation of the financial and monetary system. What he finds is that the generation of money in Russia is largely endogenous and that there is no evidence of crowding out. This is consistent with Russia being a potential candidate for monetary sovereignty in the sense that MMT suggests.

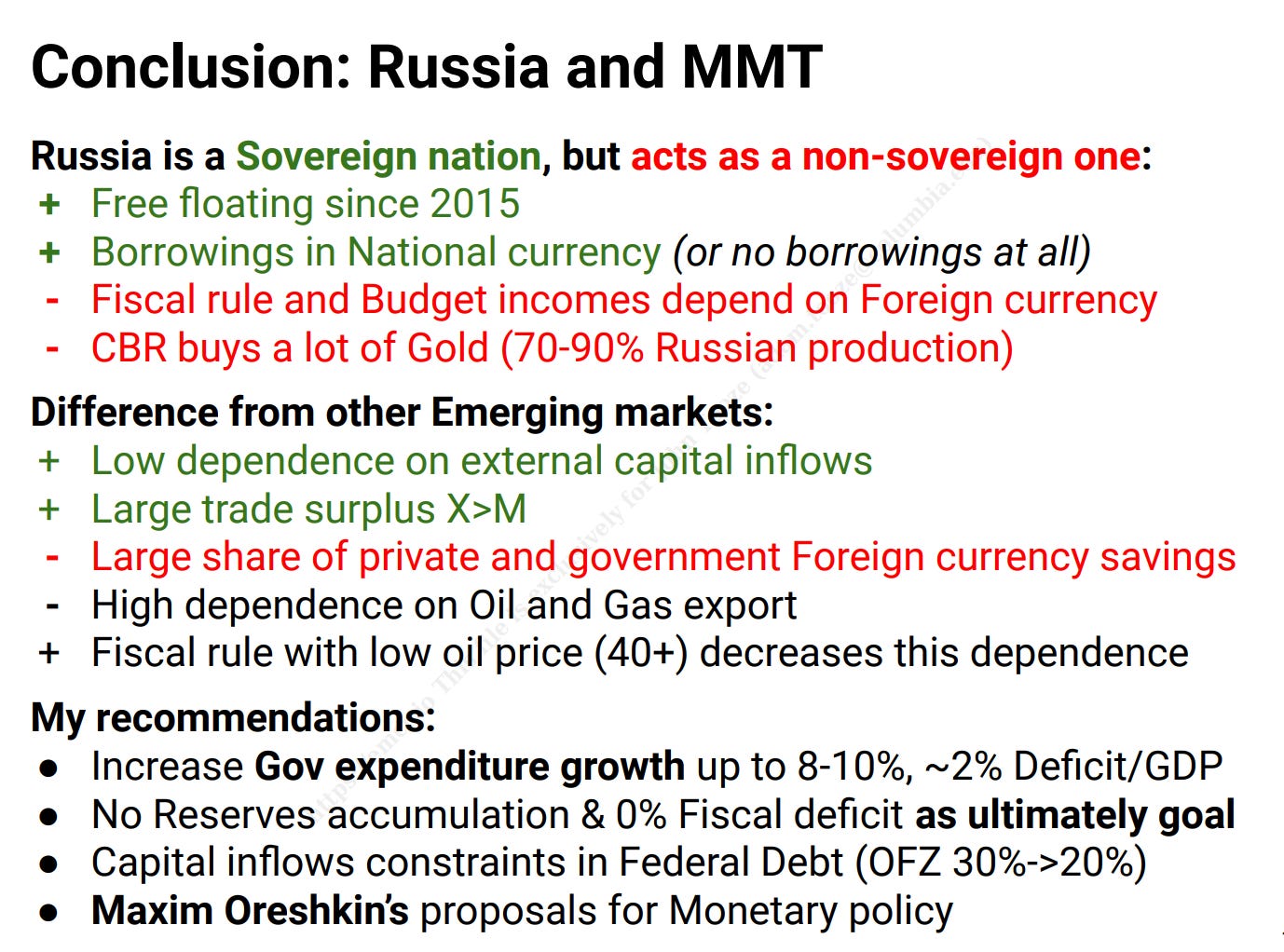

Victor Tunyov conducts a more searching exploration of the application of MMT to Russia as an emerging market economy and he does so in direct dialogue with Oreshkin’s take on MMT.

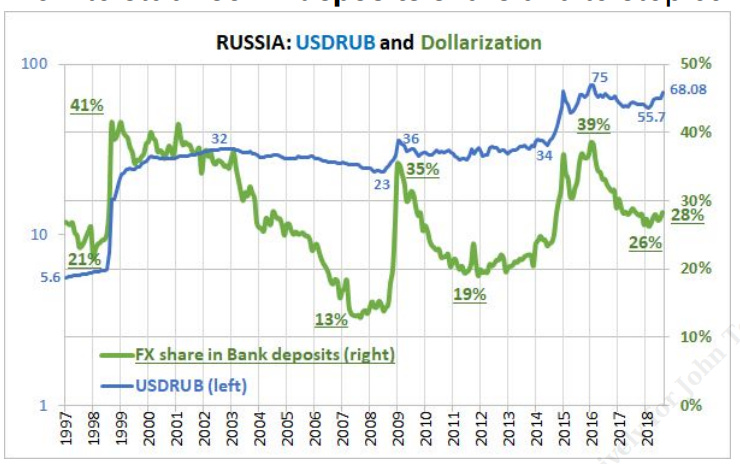

As Tunyov points out, up until the current crisis, one of the key constraints on Russian monetary sovereignty was the degree of dollarization of private accounts.

The risks, in his view was manageable.

The debate about MMT seems to have died down somewhat since 2020. The shock of COVID in Russia was severe. After the government in which he served was replaced en bloc, Oreshkin was appointed as one of Putin’s advisors on economic affairs.

In light of today’s developments Tunyov’s conclusions are truly haunting. As he put it in 2019, “Russia is a sovereign nation, but acts as a non-sovereign one”.

The current crisis has cast off any illusions on the score of sovereignty. Russia is indeed sovereign. It has violently asserted that. The question is, will it adopt an economic policy to match? Certainly with foreign exchange controls in place, questions of monetary sovereignty can be set aside for now. It is asserting an embattled sovereignty.

Here is Oreshkin on 28 February 2022 contemplating a darker future.

Elvira Nabiullina, the head of the Russian central bank, and Maxim Oreshkin, Putin's economic advisor, look like they are thinking hard about what to do with the western sanctions. pic.twitter.com/j9l2QzSBnJ

— max seddon (@maxseddon) February 28, 2022

So with these kind of arguments floating around Moscow, here is the question.

In placing so much weight on sanctions, are we not tacitly assuming that Putin’s regime, rather than using Keynesian fiscal and monetary policy to cushion the impact, will stick to the hawkish conservatism that dominated his regime’s fiscal policy up to the recent past?

If it was the rigidity of the Russian fiscal state that hitherto translated external shocks into shocks for the Russian population, what if Putin’s regime responds to its current existential crisis by adopting a more imaginative and expansive fiscal and monetary policy?

What if, within the beleaguered fortress of Russia, Putin’s regime dissolves the bind between globalization and domestic economic orthodoxy? Since it is now in an open confrontation with the West, why should Russia not use its monetary and fiscal sovereignty, reinforced by the new regime of exchange controls, to launch a stimulus program and, in so doing, negate a large part of the impact of sanctions?

If Russia has been cast into the outer darkness, what incentive does it have to uphold its orthodox reputation in fiscal matters? In a situation of direct financial confrontation with the West, markets are no longer interested in Russia’s fiscal fundamentals. If sanctions cause the ratings agencies to write Russia down to junk from one day to the next, is it surely inconsistent to expect his regime to go on playing by the fiscal and monetary rules?

The likes of Oreshkin certainly need no tutoring on the scope of action conferred by monetary sovereignty. What if Putin answers our sanctions with a “Russian Rescue Plan”? Might that negate the impact of sanctions on ordinary Russians that we are counting on to force a shift in Putin’s position?

There are others who know far more than me about the Russian policy scene. They will be able to gauge whether the Russian leadership is capable of jumping over the long shadow cast by the financial crisis of 1998 to embrace a more adventurous policy. They will be able to judge how powerful are the currents that Vladimir Mau describes in his overview.

In general, what we need urgently to debate is the “Russia model” on which our sanctions policy is based. Currently, the model is brutish and simple. Putin is a tyrant surrounded by crooks. The main idea is to “hit the oligarchs”. That plays well in the West. It may have real effects. But we should beware translating populism into strategy. The cheering in Congress for Biden’s promise to bash the Russian oligarchs was telling.

We need a more sophisticated account of Russia’s policy-making process. And we need to check our prejudices. In assuming that sanctions will cripple the Russian home front are we assuming a rigidly conservative response by Putin’s regime? That is an assumption well-warranted by the track record of Russian fiscal and monetary policy since 1998. But will it hold up, if his regime comes under real political pressure? Given the isolation we have imposed, and the controls that Russia has had to put in place, might we see a shift in Russia from a conservative deflationary policy to Keynesian stimulus? If that happens, if Moscow uses its considerable resources to cushion the home front, how then will we maintain the economic pressure on his regime?