| Adam ToozeFeb 28 | 642 |

The Western sanctions on the Russian financial system announced over the weekend are doing their work on Monday. As far as Russia is concerned, financial markets are around the world have become a legal battlefield.

“There’s nothing certain in this environment. It’s not about fundamentals any more, it’s about compliance issues.”

— Katie Martin (@katie_martin_fx) February 28, 2022

or, as one fund manager put it to me: "Hoooooooooooooooooooooooo boy"

Russia sharply increases rates as sanctions send rouble plunging https://t.co/xclSgaMl5t

Already on Sunday the news was bad.

Ruble is not yet open, and might not even open on Monday. Local bank apps are quoting 150$ and ATMs are running out of cash.

— Elina Ribakova 🇺🇦 (@elinaribakova) February 27, 2022

Capital controls and massive rate hikes next (to 20%?) next. Question is if gradual or shock and awe on the already decelerating economy. https://t.co/LF2wi0VJ3R pic.twitter.com/l1hPaEKbMz

Most devastating of all was the threat to freeze the assets of Russia’s central bank in Europe. Without the central bank in support, rumors were of a collapse in the rouble by as much as 50 percent. Overnight on Sunday to Monday, in Sydney and Hong Kong international trading in rubles more or less ground to a halt. As one Bloomberg report put it:

“No trades are coming through at all on the ruble,” said Nick Twidale, chief executive Asia Pacific at FP Markets in Sydney. “When anything like this happens, we cut leverage and basically tell people to close positions. It’s just too high risk.”

The scale of dislocation is unprecedented in a market as large as that for roubles and Russian financial assets.

“The SWIFT sanctions in effect have closed Russia’s capital account,” said Peter Kinsella, global head of foreign-exchange strategy at Union Bancaire Privee in London. “This means you’re likely to end up with huge differences between offshore and onshore pricing. This is a new paradigm for the ruble.”

Anticipating the collapse, on Sunday Moscow saw panic buying of luxury goods that may have high resale value.

The operations of Russian banks in the West are under pressure. Over the weekend the ECB announced that Sberbank’s European branch was failing.

The European Central Bank took action on Sberbank Europe AG and its Croatian and Slovenian subsidiaries after determining that, in the near future, the bank is likely to be unable to pay its debts or other liabilities as they fall due. Sberbank Europe had 12.9 billion euros ($14.4 billion) of assets at the end of 2020, according to its website.

In London its listing collapsed.

The Moscow Stock Exchange is shut for now, but Sberbank has a London listing and has just collapsed 74% on opening pic.twitter.com/HMWhB0jYz3

— Robin Wigglesworth (@RobinWigg) February 28, 2022

Gazprom likewise at one point fell in London by 40 percent. How will Russia cope?

The Russian central bank has since 2008 acquired a wide range of tools to dampen stress in financial markets and limit their impact on the real economy. As Vladislav Inozemtsev put it on the invaluable Riddle website:

The Bank of Russia now has all the necessary support tools for the market (starting from the ability to allow financial institutions not to reflect losses from the revaluation of securities on the balance sheet to interventions in the foreign exchange market and provision of ruble and currency liquidity to banks).

Already on Sunday the bank announced across the board support for the financial system.

(Reuters) -Russia's central bank announces a slew of measures to support markets as it scrambles to manage the fallout from Western sanctions, including:

— Phil Stewart (@phildstewart) February 28, 2022

* Buying gold on domestic market

* Repurchase auction with no limits

* Easing curbs on banks' open foreign currency positions

It is also moving to block the exit for foreign investors, who can no longer liquidate financial assets they hold in Russia.

BREAKING – The Russian central bank has ordered market players to reject foreign clients' bids to sell Russian securities from 0400 GMT on Monday, according to a central bank document seen by Reuters.

— Phil Stewart (@phildstewart) February 27, 2022

The bank did not reply to a Reuters request for comment.

The latest report is that Russia will force companies to sell 80% of their foreign currency earnings – in other words buy rubles. This in effect substitutes private balance sheets for the central bank which is sanctioned. It is a de facto form of exchange controls.

Whether this will be enough to hold the system together only time will tell.

On Monday the first line of defense was to hike interest rates to a punitive 20 percent and put back the opening of markets until 3 pm Moscow time. All the trading up to that point consisted in Westerners unwinding exposed Russian positions.

As the FT reported:

Russia’s biggest foreign bond, a $7bn bond maturing in 2047, halved in price to 35 cents on the dollar, according to Tradeweb data. Investors said the market was extremely hard to trade. “If you see a quote on the screen it might be live or it might not,” said one. “There’s nothing certain in this environment. It’s not about fundamentals any more, it’s about compliance issues.”

The collapse of the Russian currency may have deep political implications. As Ben Judah put it, the current collapse to him was reminiscent of the

… worst day of the 1998 collapse. Gleb Pavlovsky once told me the default that followed was the “second founding of the state.” I am certain the crash we are about to see will in many ways come to be the third.

The Kremlin is not in denial about their effects

Putin will chair an emergency meeting with his cabinet and the central bank later today after sanctions “significantly changed Russia’s economic reality,” the Kremlin says.

— max seddon (@maxseddon) February 28, 2022

“These are heavy sanctions, they're problematic, but Russia has the potential to compensate the damage.”

Beyond the immediate market turmoil what are the consequences of freezing Russia and its reserves out of the global financial system?

There are, at least, three ways to think of Russia’s reserve assets.

The first and most obvious way to think of Russia’s reserves is as a national strategic buffer. This is how they functioned in 2008 and 2014. When Russia’s financial system and currency come under pressure, dollars and euros from the reserve can be sold for roubles, thus propping up the value of the currency and slowing the process of devaluation, giving debtors the chance to unwind their exposure to foreign creditors and providing relief to importers and consumers.

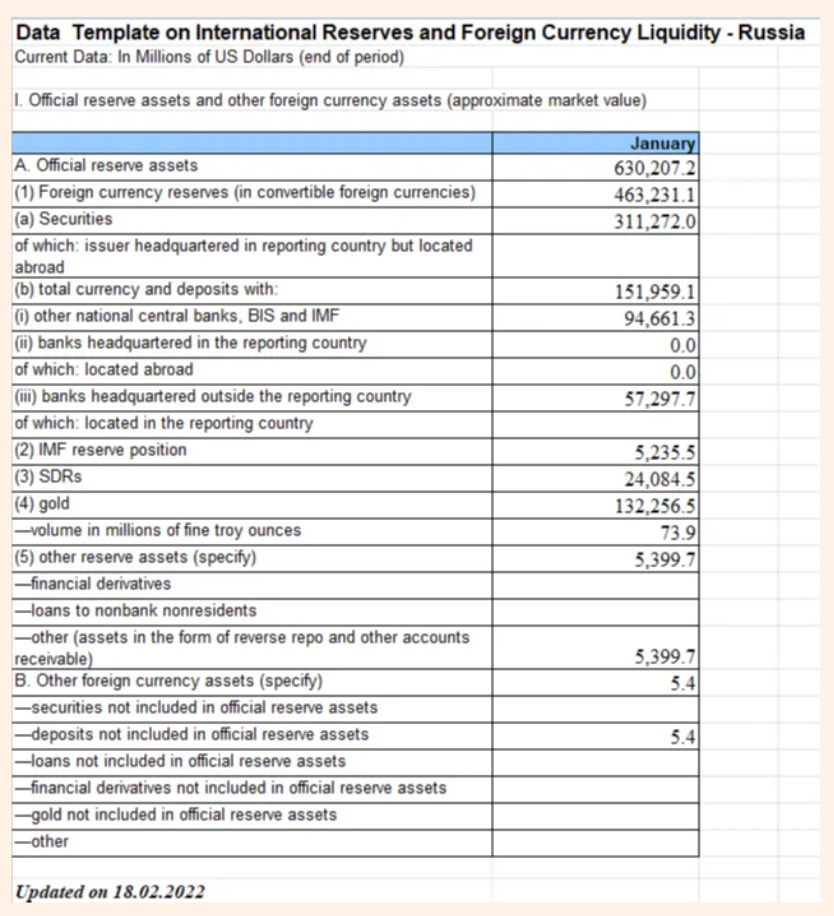

What has changed is that the unprecedented step to sanction the Russian central bank will likely make a large part of Russia’s reserves unavailable to Russian policy makers. This is the best compilation of those reserves, from the indispensable Matt Klein.

Source: Matt Klein

The mechanics of sanctions are extremely well explained in this piece by Claire Jonesand Joseph Cotterill of the FT’s Alphaville. A must read.

The crucial thing is that reserves of euros and dollars can be put to work only by selling them in western financial markets. Those transactions require intermediary banks. And those banks can be blocked from engaging in transactions involving Russia’s central bank. To do this to a fellow central bank involves breaking the assumption of sovereign equality and the common interest in upholding the rights to property. It is a major step not easily taken against a central bank as important and as much part of the Western networks as the central bank of Russia. It was not, as far as I am aware, contemplated in 2013-14.

A second important way of thinking of the reserves is as a surplus of unspent revenue squeezed out of the Russian economy that has been deliberately throttled to generate a surplus in the hands of the state. This is the perspective that Nick Trickett highlighted in his excellent piece on “The false strength of Russia’s currency reserves”.

Seeing the reserves that way suggests that financial strength in the hands of the state will go hand in hand with weaker private balance sheets. And this will, indeed, be the test in weeks to come. How will Russian households and businesses cope?

Hard-hit banks are raising interest rates to their customers. That will apply a painful squeeze to real estate markets and indebted households.

Russia’s VTB bank – the country’s second largest which is now under heavy sectioned – will raise interest rates for new mortgages by FOUR percentage points.

— Jake Cordell (@JakeCordell) February 27, 2022

New mortgages will have an interest rate of 15.3%.

But there is a third way of thinking of the Russian reserves:

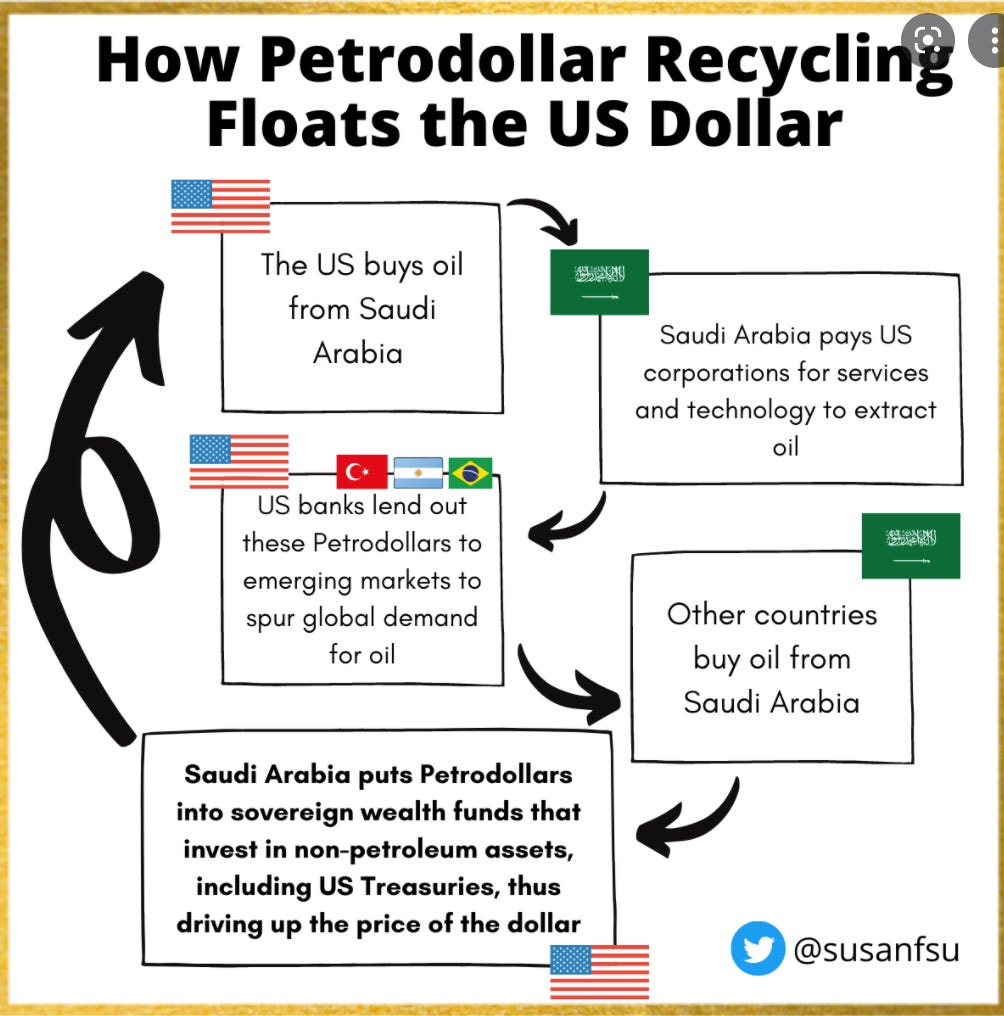

They are petrodollars. The export earnings of an oil and gas exporter. And the thing we know about petrodollars is that they are recycled. Conservative fossil fuel exporters do not simply blow the money they earn on immediate imports, they lend the money they earn from selling oil and gas back to their customers, building financial claims or, which is. the same thing, providing funding to global financial markets. Oil and gas are thus converted into a lasting stream of interest payments and dividends.

The classic model of petrodollar recycling that first emerged after the 1973 oil crisis, functioned something like this:

Source: Susan Su

The crucial point that this highlights is that Russia’s reserve accumulation, like reserve accumulation by other oil and gas producers such as Norway or Saudi Arabia, is a source of funding in Western markets. The reserves do not simply sit idly in central banks accounts, they are lent out. With sanctions, the funding provided by Russia’s petro- and gas-dollars is in jeopardy. And that impacts not only the Russians.

If you sanction Russia and thus block hundreds of billions of dollars in the global balance sheet, you have to ask yourself: what happens to the other side of the balance sheet? Reserves are Russia’s assets, they are someone else’s liabilities, who in turn has balanced that liability with an asset and so on. Those chains can be ramified and complicated.

In the 2000s like China and Japan, Russia bought US Treasuries. In effect, it became a creditor of the US government. That provoked unease on both sides culminating in 2008 in the (likely exaggerated) rumor that Russia was urging China to join it in a “bear raid” on the US Treasury market – selling US government debt deliberately to provoke a market slump.

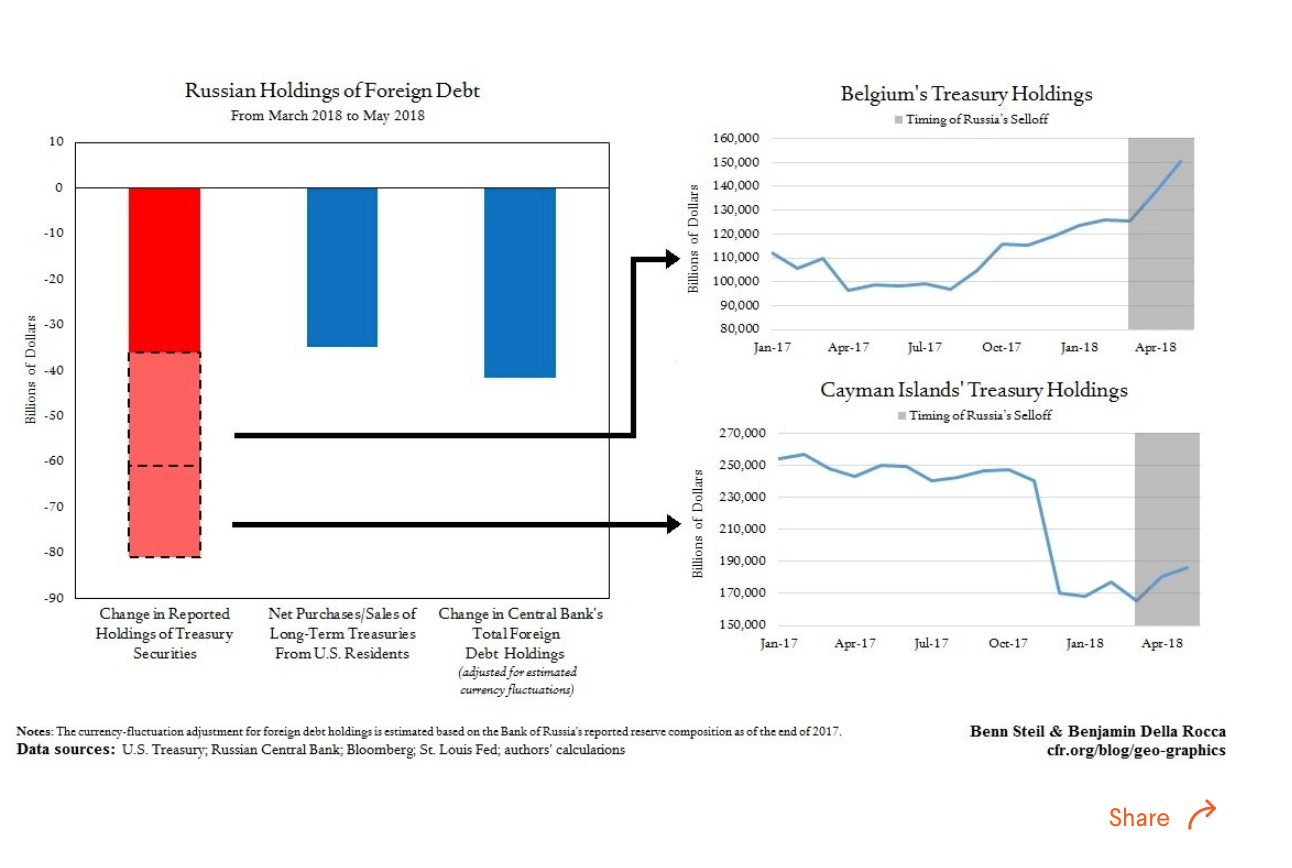

What is not disputed is that in 2018 under threat of sanctions Russia slashed its official and direct holdings of Treasuries. There are various theories as to what happened next. Where did the billions go?

One explanation offered in 2018 by forensic work done by Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca of the CFR is that the Treasuries were moved offshore, out of US jurisdictions, to holdings in Belgium and the Cayman Islands.

That seems a convincing explanation at least for the first stage. It would mean that Russia remained as a de facto creditor of the US government, just from the safety of an offshore haven.

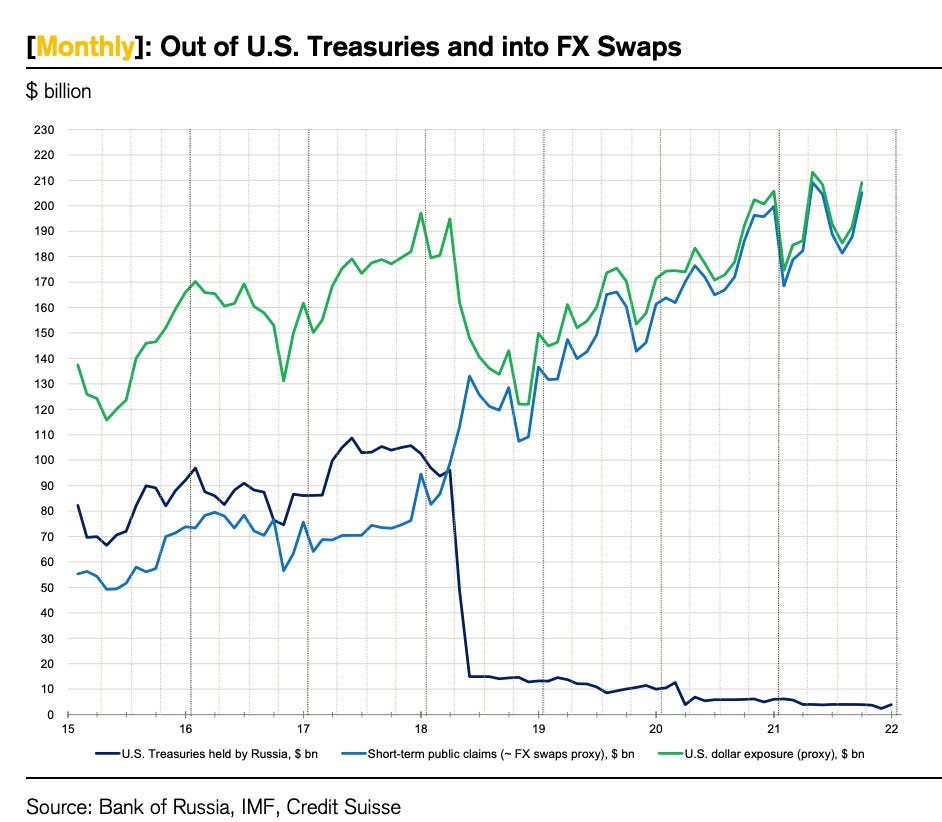

Since that first sell-off in 2018, as Zoltan Pozsar of Credit Suisse has argued in his “Global Money Despatch”, Russia’s dollar holdings have been put to work increasingly not in the market for long-term government debt, but in short-term money markets. Russia’s money was moved out of US Treasuries and into FX swaps, in which Russia lent dollars in exchange for non-dollar collateral. The Russian side of that pairing of assets and liabilities, Pozsar suggests, is what shows up in Russian holdings of reserve deposit in non-US central banks. Those are what is being sanctioned as of this morning.

Source: Zoltan Pozsar Global Money Despatch Feb 24 2022

The Russian funds in European central banks are not simply pools of money sitting idly. They are part of complex chains of transactions that may now be put in jeopardy by the sanctions.

As Pozsar puts it a large “surplus agent” has been removed from the system.

Consider for example if funds get frozen through sanctions – an event that would turn a surplus agent (Russia) into a deficit agent, which in turn would lead to missed payments, much like the onset of Covid-19 led to missed payments and turned surplus agents into deficit agents.

All told, Pozsar estimates that Russia may be responsible for providing in the order of $300 billion in funding to short-term money markets. If that funding disappears overnight it may deliver a serious shock to the Western financial system.

How serious remains to be seen, but the implication is that it is not only the Russian central bank that may come under pressure. Central banks in Europe and the Fed may need to stand by to make markets in the way that they did in 2020.

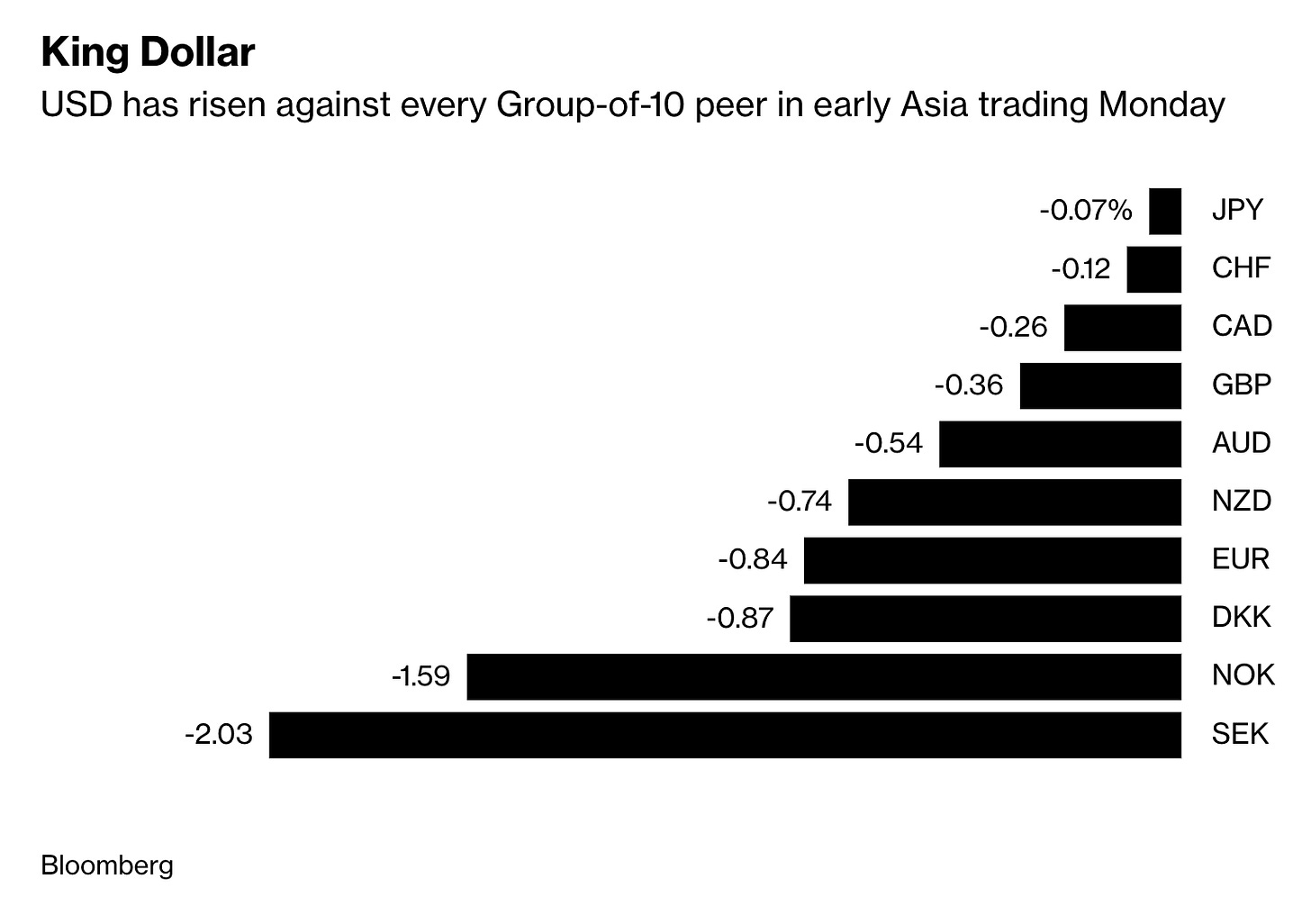

And this is true more generally for global financial markets at a time of huge uncertainty. As at the time of the COVID shock we are seeing a surge of demand into dollars, as a global safe haven.

That in turn puts pressure on everyone who has borrowed in dollars. This is a pattern we have seen repeatedly in moments of crisis since 2008: A global dollar shortage.

This is important to weigh against the speculation out there right now about the long-term impact of sanctions. Will it drive China to diversify further away from the dollar? Will alternatives to SWIFT take shape? Certainly Russia will need to get busy coming up with alternative payment mechanisms, that might run by way of the Renminbi or the Rupee.

As Ousmène Mandeng told the FT, one option would be the following:

Russia may accept payments for its exports in renminbi and increase imports paid in renminbi from China and possibly other countries accepting renminbi. As renminbi-based payments will most likely be conducted by institutions outside the immediate influence sphere of the West, this would work. … It would mean reorganising Russia’s international financial and economic relations, but that may be something it has been pursuing in any event.

But important though this shift may be, in the short-run the dollar is still king. And in the end there is only one unlimited source of dollars for the world economy, the Fed.

Never a crisis that the dollar doesn’t come out more dominant from, it seems. @DavidBeckworth https://t.co/KuKWLt98zM

— Nicholas Mairone (@nicholasmairone) February 28, 2022

So that is the next question for markets to digest. How will global demand for dollars as a safe haven, mesh with the Fed’s desire to tighten policy to counter inflation? Put the two together and you have the makings of a crushing dollar squeeze. Even before the crisis became acute there was worry about how the Fed could square the domestic priority of price stability with the stability of the global dollar system. That balancing act just got even harder.