We are in truly dangerous spiral:

— Adam Tooze (@adam_tooze) February 26, 2022

Brave Ukrainian resistance frustrates Russian attack -> Kiev refuses humiliating negotiations.

Russia about to ramp up destructiveness of attack

NATO members rushing weapons to Ukraine

EU/US announce major sanctions.

What is Russia’s next move?

That was Saturday evening, after the news began to sink in of another day of heroic Ukrainian resistance, a new wave of arms supplies from the West and the coordinated escalation of financial sanctions between Europe and America .

What was Moscow going to do?

As Kardi Liik puts it here, we were waiting to see Moscow’s response. It was not likely to be symmetrical i.e. economic counter-sanctions responding to the West’s financial measures. Russia would choose the terrain on which it feels it has relative strength.

Good thread by Sam.

— Kadri Liik (@KadriLiik) February 27, 2022

Just one thing: should Moscow start feeling existentially threatened, it would likely not respond by counter sanctions, etc. I fear it’ll decide that the economic playing field is tilted towards the West & choose the means where Moscow has the edge https://t.co/4X9c4trxIG

Within minutes of her tweet, the news broke of Putin’s nuclear threats aka “nuclear signaling” and a major motorcade leaving Moscow.

So far today these are the most technically sophisticated commentaries I’ve seen on the nuclear escalation.

What is this "special mode of combat duty of the deterrence forces"? Hard to tell with certainty, but most likely it means that the nuclear command and control system received what is known as a preliminary command https://t.co/uQwfWNyCX6 1/8

— Pavel Podvig (@russianforces) February 27, 2022

<THREAD>What does raising the alert level of Russian nuclear forces entail?

— (((James Acton))) (@james_acton32) February 27, 2022

Russian nuclear forces can be divided into strategic (which can reach the US) and nonstrategic (which can't.) I'm looking to see whether strategic forces, nonstrategic forces, or both are alerted. (1/n) https://t.co/Mx54KMoSv1

It isn’t the financial sanctions alone that explain this dangerous escalation, but the combination of all three factors – Russian military frustration, increasingly emphatic Western commitment to backing Ukraine’s remarkable resistance and the sanctions on top. This forces Putin to look for a qualitatively different means to respond to an increasingly existential situation.

As one of our leading military experts comments, the way to rationalize Putin’s behavior is to assume that he expected a rapid and crushing battlefield victory. That would have minimized the risk of an upsurge in Western public opinion and a dramatic reaction by Western governments.

What Putin has done is going to be an absolute catastrophe for the Russian economy. I have no idea how he expects to withstand the fallout. Repression can only achieve so much. I think they somehow imagined winning quickly & easily, avoiding the harshest Western sanctions. https://t.co/Y1Mob7igEf

— Michael Kofman (@KofmanMichael) February 27, 2022

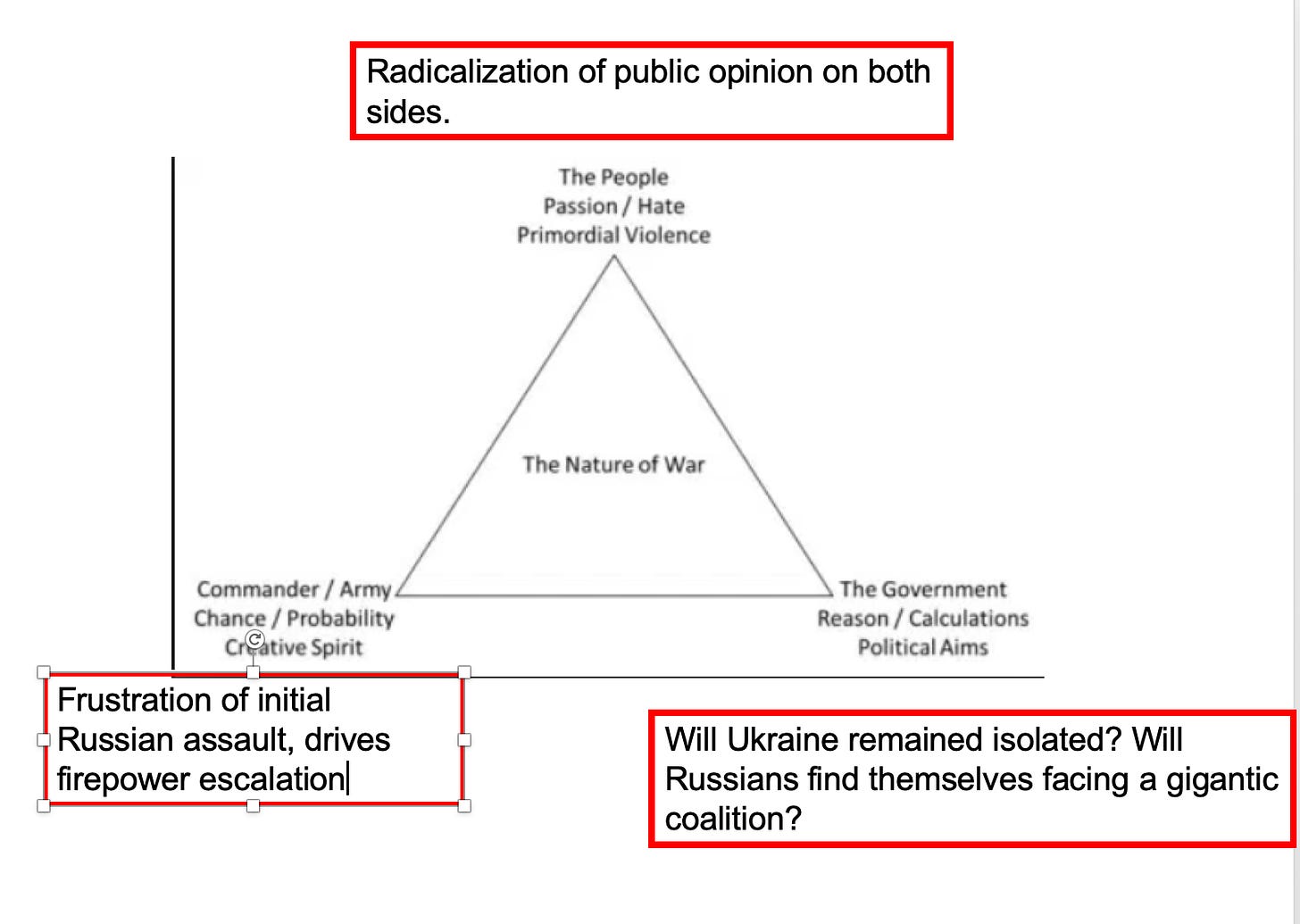

It is the Clausewitzian trinity working with terrifying force.

Clearly, the mood in the West has shifted dramatically. The most obvious symbol of this is the decision by the German government to supply combat weapon and to establish a 100 billion euro defense fund, a decision that clearly unites all three parties in the coalition government.

Amazing. German finance minister @c_lindner – traditionally a fiscal hawk – just disparaged leader opposition @_FriedrichMerz for warning that higher defense spending could increase public debt. Says it’s first and foremost an investment in our freedom. pic.twitter.com/wvXAnFxXTF

— Olaf Storbeck (@OlafStorbeck) February 27, 2022

So if this logic continues to operate, what will drive the escalatory spiral are

1. potential nuclear counters from the West

2. decisive events one way or another on the battlefield in Ukraine

3. what impact the sanctions actually have on Russia – economy, society, politics – in the coming days.

Over the last week, we have seen how the reality of war, the shock of moving from hypothetical to reality, changes the calculus. That is the stage we are reaching with the economy next week. The shooting has started. What will be the fall out? The truly concerning prospect should be that a general panic in Russia, triggers a further dangerous and unpredictable military escalation.

It is very hard to gauge the full impact at this point because we don’t know what was actually decided in the financial sanctions packaged announced on Saturday evening.

What is clear is that the Europeans and Americans decided to shift the “Overton window” and bring SWIFT and the central bank into play.

They promised to cut some Russian banks out of SWIFT and take measures to ensure that Russian central bank assets in the West could not be used to circumvent sanctions. Since many of them may be in the German Bundesbank that is a serious threat from Berlin.

In Chartbook #87 I tried to map what the implications might be. But as my old friend and ex-US government sanctions expert Eddie Fishman points out in this excellent thread, the details are as yet unclear.

The US, EU, Canada, & the UK just released a joint statement committing to several major sanctions actions, including a SWIFT ban and restrictions on the Central Bank of Russia. This is a big deal, but details will matter. Here's my initial analysis (🧵):https://t.co/rJ19sgpdcs

— Eddie Fishman (@edwardfishman) February 26, 2022

Which banks will be cut out of SWIFT? Will it be Sberbank, VTB and Gazprombank?

On the Russian central bank, will it be a blanket blocking attempt or something more surgical? As of the time of writing on Sunday morning East Coast time, we do not know.

Potentially it is a truly dramatic step. As the FT reported

Josh Lipsky, director of the Atlantic Council’s Geoeconomics Center who previously worked at the IMF, said before the announcement that hitting the central bank would be an “extraordinarily significant and damaging move” to Russia’s economy. “A G20 central bank has never been sanctioned before. This is not Iran. This is not Venezuela,” said Lipsky.

As Fishman explained to the FT, the ultimate sanction would be to add the Russian central bank to the Treasury’s “Specially Designated Nationals” list, that would effectively excluded it from the global financial system. “It would render a sizeable chunk of their foreign exchange reserves unusable overnight” – in the order of $300 billion – Fishman added.

But, for all the fire and fury, the FT team also reported the following:

The goal will be to avoid undermining mechanisms for western economies to purchase energy from Russia. The allies have not finalised the details, but will either carve out certain energy-focused banks or use product definitions in the Swift system to permit energy-related transactions.

In other words, sanctions will be designed to enable continued flows of payments to Russia for energy.

That certainly was the mood in Berlin for much of Saturday – “selective”, “careful”, “so as to hurt them and not us”. That is not all out sanctions, which entail demonstrating precisely that you are willing to take pain so as to inflict pain. There is still a gap, in other words, between the sanctions language of the West – measured, selective, economically rational – and the Mutually Assured Destruction calculus towards which Putin seems to be escalating. He is playing the “madman” to our surgical strike. It is a very dangerous combination.

And as on the battlefields in Ukraine, things may transpire in the course of this escalation that add to the dynamic in an unpredictable way.

As far as the economy is concerned, the central question is what will happen in Russia what will happen in Moscow and in financial markets on Monday?

Will economic and financial chaos add a qualitatively new element to the escalatory logic. Clearly, at this point the West really is aiming to inflict heavy damage. But we should be prepared for the fallout, forgive the phrase, if things get chaotic next week. Are we ready for a further escalation of nuclear threats?

As James Acton rightly insists, as unpalatable as it may be, we need to think about what off-ramps we can offer Putin.

In determining the pace of escalation, the situation on the Russian home front will become very important.

Sam Green of KCL has an important thread on this. As he puts it, it is not clear at this point whether we should be impressed by the calm of the Russian population so far, or worried by it.

Sanctions have very rapidly escalated, as transatlantic consensus has consolidated. Two key things to note now:

— Sam Greene (@samagreene) February 27, 2022

1) Escalation is proactive, not reactive, for the first time since 2014;

2) Moscow has not responded. https://t.co/9gy08t4YoH

If Russians are calm, does that mean that they are not prepared. Will they then panic when the reality of disaster sinks in?

How would Putin’s regime respond to a widespread public panic triggered by Western sanctions?

How resilient is the Russian home front in this economic war?

Yesterday, Nick Trickett @ntrickett16 (an essential follow on Russia) passed on to me some of his fantastically interesting work on the Russian domestic economy.

Following logic that parallels that of Matt Klein and Michael Pettis in their critiques of trade surplus-nations Russia and China, Trickett asks:

Can an economy with a trade surplus (and a fx reserve) as large as Russia’s really be described as “healthy”? What is the price that you pay for building a fortress balance sheet and does it make your home front fragile when push comes to shove? In the extreme case we now find ourselves in, not only are the fx reserves vulnerable to blocking, but your domestic economy may have been weakened in the course of building the reserve.

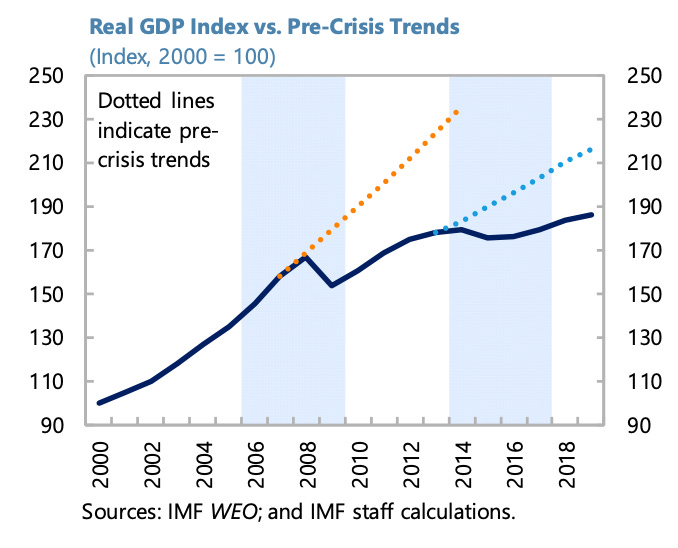

Russia’s system of reserve accumulation originated in the financial system of Alexei Kudrin who served as Russia’s Finance Minister between 2000 and 2011. He used fx reserve accumulation to hold the exchange rate of the ruble down, maintain the “competitiveness” of the Russian economy and build financial resilience. It was a Russian, fossil-fuel-based version of the Chinese formula. High growth, low domestic consumption, large export surplus, large reserve accumulation. It paid off for the regime in both 2008 and 2014 in providing resilience against both financial and geopolitical shocks.

The flip side of this strategy, in Russia, as in China (and Germany), is diminished domestic demand, both in the form of repressed consumption and domestic investment. And, since the first Ukraine crisis, the price has been much slower growth.

As Trickett goes on to argue, in excellent neokeynesian style, one cannot analyse the public account in isolation. A fiscal surplus will, all things being equal, go hand in hand with borrowing in the private sector. In the last few years, both Russian corporations and households have been borrowing which leaves them exposed in the current crisis.

Between January 2020 and January 2022 alone, household ruble-denominated debts rose by roughly 7.2 trillion rubles amid conditions of real income decline for many and rising prices, over 5% of GDP. By comparison, business ruble debts have risen to just 8.47 trillion rubles in that timeframe as state policies intervened. Households bore the brunt of the COVID shock.

In December 2021 the World Bank remarked:

Accelerated household lending growth may contribute to retail consumer over-indebtedness and assetquality deterioration in the future (Figure 1-50 and Figure 1-51). In contrast to corporate lending, retail – or household – lending saw an increase in mid-2021 with mortgage lending remaining high and other lending types increasing. Since then, retail credit has cooled somewhat, but was still growing at above 13 percent in real terms in October. The share of risky loans to households whose payment-to-income (PTI) ratios exceed 80 percent edged up to 30.3 percent in Q2 2021, higher than the pre-pandemic level of 26.7 percent. Continued rapid retail credit growth may weaken the effectiveness of monetary policy in dampening demand-driven inflationary pressures. In this respect recent, prudential tightening measures taken by the authorities will support policy alignment.

So there is considerable financial fragility in Russian society that may be triggered next week.

Meanwhile, this is the latest prediction for the Russian rouble tomorrow.

Tinkoff saying 153 for rouble tomorrow m. https://t.co/Ar6FiSIxHy

— Timothy Ash (@tashecon) February 27, 2022

153 as compared to 83 at the end of last week. A huge shock to the Russian home front.

In 2014 Russia suffered a devaluation of massive proportions, but the sanctions were much less intense and the military battle was going in its favor. We have nothing that tells us how Putin’s nuclear-armed regime reacts under this kind of financial pressure, when it is also facing an existential military crisis.

Could we, as Lawrence Freedman suggests, be at the phase of escalate to deescalate.

But it may also serve (optimistically) as an ‘escalate to de-escalate’ moment – raising the stakes to provide cover for finding a way out if this mess (especially as now tentative p ace talks may be getting under way.end/

— Lawrence Freedman (@LawDavF) February 27, 2022

Perhaps, but the worrying thing is precisely that as far as the economy is concerned, the chaos is just about to get started. Clearly the economy has not been the determining factor in Putin’s calculus so far. Sanctions were intended to get his attention. Next week will reveal how that message lands.