“We have a powerful weapon to fight inflation: price controls. It’s time we consider it.”

Last week, Isabella Weber’s op-ed in the Guardian, which – on the basis of positions taken by prominent American economists in 1946 – advocates “strategic price controls” as a means to controlling profit margins and inflation, has caused quite a storm.

I’m late to the game having been on a break from social media visiting in-laws in rural Kentucky.

Coming back to twitter this week, the ugliness of the reaction to Weber’s op-ed is depressing. Perhaps one should not be surprised. But it is depressing and telling, nevertheless.

I would much prefer to discuss the substance of the issues and I will do so below. But one should not pass over the tone of this debate without comment.

When it comes to the politics of intellectual life, I’m committed to showing not telling. Chartbook is part of that effort. But given the importance of the subject matter and since my name was invoked in one widely quoted thread, forgive me for making an exception in this case.

In this kind of debate there should be no room for disrespect. Full stop. However wrong and ill-judged you may feel Weber’s op-ed to be, there should be no room for disrespect. It was good to see Paul Krugman apologizing. But the harm was done.

This is not merely a matter of etiquette, manners, or personalities. In the tone of a debate, issues of professional authority are at stake. If the personal is political, so too is the tone of a debate.

Regrettably, the aggression triggered by Weber’s op-ed is also profoundly unproductive in intellectual terms. It turned what should be a serious argument about an important issue – the means of inflation-control – into an ugly slanging match. This is not by accident. One way to shut down an unwelcome discussion is by means of fist-pounding. Another is the tantrum. In either case, the unproductiveness of the ensuing conversation is not a bug. It’s a feature.

***

Weber’s op-ed is short on substance. She does not tell us what kind of price controls she advocates, on what sectors etc. But, in fairness, the op-ed links to work that is more specific.

If you are serious about engaging in the argument, don’t focus on Weber’s 800 word squib, read it in light of her important historical work on price control politics in the West and China after 1945, which poses its own questions. And acknowledge the fact that her suggestion is not without context. It reflects a rich vein of recent post-Keynesian writing that has urged “unconventional” approaches to inflation control.

I say post-Keynesian deliberately. Tilting at MMT was another of the distractions of the price control debate on twitter.

What can we salvage from the wreckage? How can we take this debate in a more productive direction?

As Eric Levitz makes clear in his excellent write-up of the debate, whether you find Weber’s op-ed convincing or not, there is a serious position to be argued with. The effort to assert the monopoly of conventional inflation-fighting disarms us.

One could make a strong case for more stringent controls throughout the American health-care system. And price controls are themselves just one of many unorthodox approaches to inflation management. Reducing the monopoly power of price-gouging firms, channeling credit to sectors where demand outstrips supply, forcing (or strongly encouraging) workers to save a fraction of their paychecks, and direct public investment in expanded production are others.

All of these measures have the potential for negative side effects and unintended consequences. But the same can be said of raising interest rates. If policymakers reflexively presume the wisdom of conventional tools, and dismiss the potential of unorthodox ones, we will all pay the price.

On the history of price controls in the US since 1945, follow the excellent Andrew Elrod, whose PhD is going to make a major impact. Start with this thread.

Exasperating to see price controls hitting such a raw nerve in real time over the past few days on here. Guess the Cold War isn't over after all!

— Andrew Elrod (@andrewelrod) January 2, 2022

It includes this great line: “Informed debate then was never about whether prices should be controlled but who should control them.”

For a serious discussion of how price controls have actually operated in the US up to the present, check out this piece by Todd Tucker.

For post-Keynesian proposals on how regulations and price controls of various types might assist in managing America’s current inflation problems, check out the position of Josh Mason and Lauren Melodia at the Roosevelt Institute.

Having said all that, I remain unpersuaded that price controls can be an important remedy in our current situation.

***

Some are skeptical because they believe that inflationary pressure is broad-based and merits a monetary policy response.

For my part, I’m a paid-up member of team transitory, a diagnosis Weber mentions but does not seriously address. In fact, I am not just part of team transitory. I am a member of team sectoral, as well. To put a point on it, I am not convinced that the current round of price increases should really be thought of as a general inflation at all. I am impressed by recent BIS work which shows the common factor in recent price movements declining in significance. And if that is true for data up to 2019, it is all the more the case for the period since the COVID shock. Matt Klein’s breakdown of the data into COVID and non-COVID elements is highly persuasive on this score.

If one takes this approach, the question becomes which instruments might usefully address which drivers of which price increases. It is not obvious to me that either interest rate hikes or price controls in general can be of much help.

Weber starts by stressing rising profit margins as an important driver of general inflation. On that score I find the critique by BLS-financial analyst and Substacker Joseph Politano wholly persuasive. It just isn’t likely that a general surge in profit margins is doing the damage here.

Likewise, I find Politano’s breakdown of the sectoral logic of inflation highly persuasive as well as his skepticism towards price controls as a means of addressing inflation in energy prices, for instance.

There is no doubt a case for driving down the price of pharmaceuticals in the US. Rent controls may be part of housing-policy trade-off in some cities. The meat lobby has an anti-trust case to answer. But I see little advantage in packing an array of discrete measures using existing instruments under the (deliberately) provocative rubric of “price controls”.

I don’t think it is pejorative to describe the use of the term “price controls” as provocative. I take it to be the purpose of this language to provoke debate and break open the confines of conventional discourse.

But as desirable as that kind of heterodox challenge may be in general terms, we will be kidding ourselves if we imagine that such measures are a “powerful weapon” to fight the spike in prices in 2022.

Cleaving to team transitory does not imply complacency. It just implies that faced with a range of bad options we should practice restraint in adopting any anti-inflationary policy, whether that involves monetary policy, regulatory policy or fiscal policy.

***

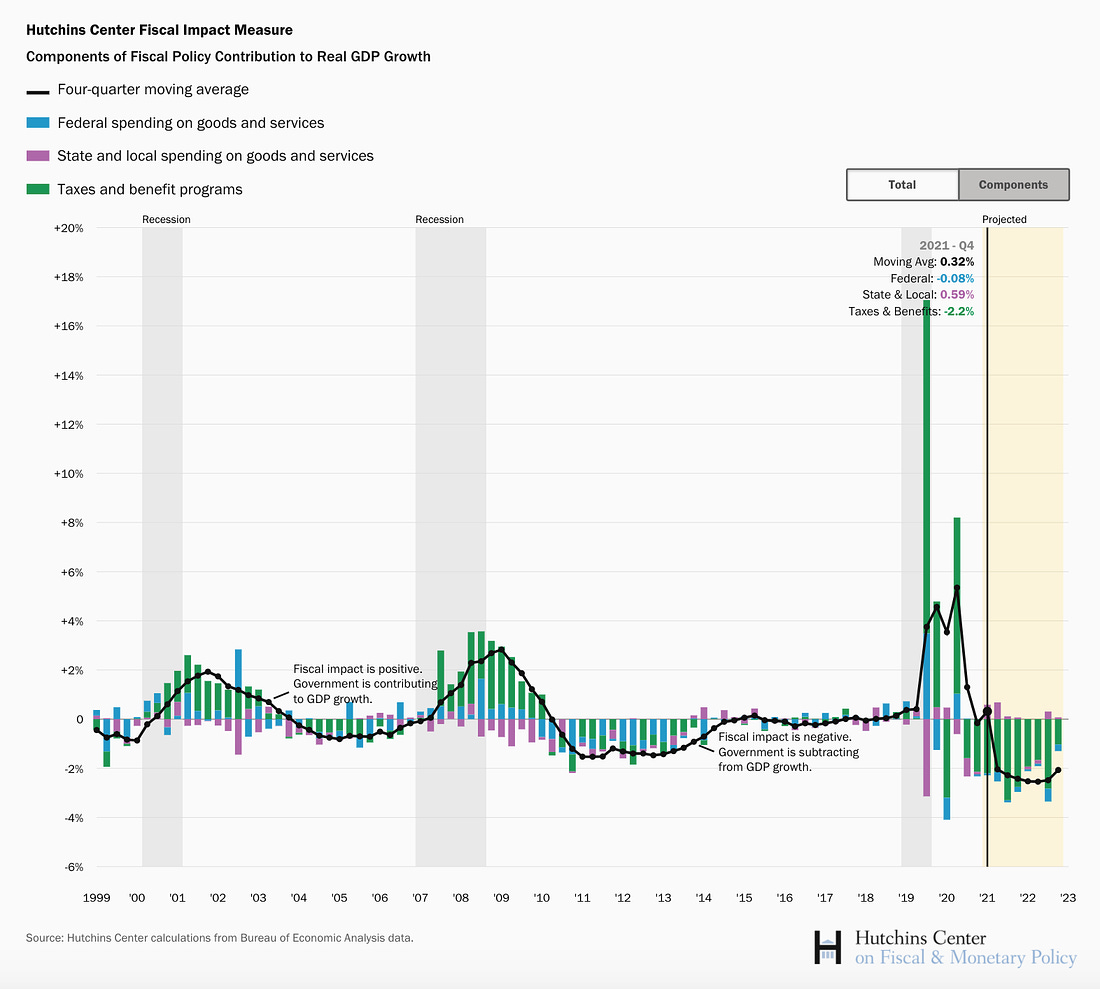

One of more striking set of data to appear of late are the quarterly numbers for fiscal impact produced by Brookings. For all the talk of Biden stimulus, the fiscal impulse went into negative territory in Q2 2021. Even on a four-quarter moving average basis it is now on the border of negative territory.

Source: Brookings

For more on the impact of Biden’s fiscal policy and the Rescue Plan in particular, check out this excellent piece by the EPI.

Though I would take issue with the language Weber uses to characterize the team transitory position – “houses on fire” etc – no one would deny that there are political risks involved in the current price surge. The Biden team clearly think it is important to be seen to be doing something about the price of petrol, meat etc.

But what purpose is served by labeling this as a policy of “price controls” and harking back to the 1940s?

On purely intellectual grounds a more wide-ranging debate is no doubt to be welcomed. But we are not in a debating club. This is the arena of high-stakes politics. What matters for the Biden administration are the midterms in 2022. Has anyone done any polling on how talk of “price controls” might play with important swing constituencies and media outlets that make a difference?

On drug prices, a large majority of Americans seem to favor robust drug price negotiations. But when the issue of price control is raised, at least one yougov poll (take it or leave it) shows little enthusiasm (and yes I am aware of the website this is published on).

Happy to be corrected on this, but perhaps an activist, tough government negotiator is more attractive than the bureaucratic visions summoned up by talk of “price control”. Certainly, the experience of 1940s control cast a long shadow over American public debate of the issue of price controls for decades to come.

Which brings us finally to the uses of history.

***

Some folks in the progressive camp are clearly convinced that taking inspiration from history, not just from the general aura of the New Deal, or from specific policies, but even from policies, like peacetime price controls, that were debated in 1946 but not implemented, is intellectually productive and politically helpful. I’ve been a skeptic on this “blast from the past”-strategy since the Green New Deal came on the scene. I find it hard to see how progressive politics benefits from this kind of historicism. As far as the Green New Deal is concerned I have come around. I’ve ended up embracing its grand vision of our historic predicament, whilst continuing to worry about strong analogies being drawn between the mid-century moment and our current situation. On those grounds I find Weber’s effort to segue from 1946 to 2022 unpersuasive.

Obviously, I share her interest in history and I share the enthusiasm for the writings of mid-century macroeconomists like Keynes, Kalecki, Lerner et al. But I am deeply skeptical when it comes to teleporting structural analyses and particular policy lessons from the mid 20th century into the present. And we should particularly guard against the kind of nostalgia that is evoked by the evocation of “If only, …..”.

In another domain of history and policy one might refer to this as the “Lost Victories” syndrome.

Precisely because the dynamic of modern history is so dramatic and so violent, because the pace at which complexity increases is so staggering, because the kaleidoscope of power and political economy shifts so radically, I don’t think that history’s role should be to invite us to refight past battles.

Nor is development all in one direction. It is far from obvious that the US government machine today would be able to mobilize the competence and resources necessary to supervise prices on a large scale. Recent experience with the provision of basic services like COVID testing hardly suggests as much. Rebuilding administrative competence may in fact be part of the underlying project of market supervision and price control. But in that case it is a long-haul strategy.

Of course, history functions in non-linear ways and it is not per se inconceivable that a “blast from the past ”, “lost cause”, “if only…”-strategy may work as a political proposition. What else did Donald Trump trade on? But it is a gamble at long odds and on any conventional understanding of progressive politics a leap back to a golden age that might have been hardly seems like an obvious move.

Faced with the drama of the great acceleration – the dramatic escalation of modern history – the more obvious role for history would seem to be to help us to understand how we got here.

Of course, Weber’s leap into the past is not unmotivated. In fact, it is warranted by no lesser authority than the White House Council of Economic Advisors. In July 2021 the formidable team of Cecilia Rouse, Jeffery Zhang, and Ernie Tedeschi issued a paper giving quasi official endorsement to the aftermath of World War II as the proper historical analogue for the present. I don’t know whether this is a historic first – for. the White House to announce its preferred historical analogue. But it is certainly a remarkable example of the instrumentalization of history.

The aim was clear. To cut off the alarming analogy to 1970s-style stagflation. As the authors conclude:

No single historical episode is a perfect template for current events. But when looking for historical parallels, it is useful to concentrate on inflationary episodes that contained supply chain disruptions and a spike in consumer demand after a period of temporary suppression. The inflationary period after World War II is likely a better comparison for the current economic situation than the 1970s and suggests that inflation could quickly decline once supply chains are fully online and pent-up demand levels off.

It is this prise de position by the Biden administration’s advisors that licenses Weber to make her move: “Well, if you want to talk about the aftermath of World War II, let us talk about price controls and the policy that was advocated at the time by many distinguished economists …”.

Thus a leap back in time by way of analogy licenses a “sideways” leap into counterfactual, along the lines of: “If only back in 1946 they had listened to Samuelson et al … Let us not repeat their mistake. Let us not shy away from what was advocated by the best and the brightest in 1946”. The dialectic of progress seems to be envisioned not so much as avoiding mistakes, but avoiding omissions of the past, missed opportunities etc.

But if you want to talk about the historical experience with price controls in America since World War II can we really do so seriously without engaging with the embattled history of those instruments when they were actually last tried in practice on a large scale? Don’t you have to engage with the historical terrain that the White House team were trying to avoid, i.e. the 1970s?

Like it or not, that is how we got here. That is the epoch that left folks like Krugman as conflicted and allergic as they clearly feel about any mention of price controls.

I am all for a creative historical reimagining of the 1970s. Releasing us from the nightmare memories of that period would do a great service to the political imagination. But price controls seem a particularly unpromising territory, particularly given the area of price inflation that mattered most, then and now i.e. energy.

If energy prices have been the largest single driver of the price spike since 2020 not just in the US but around the world, would anyone wish to repeat America’s experience with energy price controls in the 1970s? Surely not. Bullying OPEC has its attractions – think of it as the analogue to muscular negotiations over drug prices – but it also harbors risks. Not only does it promote greater oil production, which is the opposite of what we need, but it entrenches the popular sense that low energy prices are an American birth-right that is the job of government to deliver, by all means necessary.

***

By a process of elimination, the best judgement is surely what it was last autumn. If “team transitory” favored patience with regard to monetary policy that goes double for any policy of “strategic price control”.

The Biden administration has little to gain and much to lose by dramatizing the situation. By all means, go for the easy wins. So long as they do not deflect from strategic objectives like decarbonization. Pick off the profiteers. Use the tools that are available. But let us not confuse our situation today with that facing the United States after World War II. We are far removed from that epoch, both from its dangers and its possibilities. We have our own problems to face, let us address them on their own terms rather than rummaging in the locker of the mid twentieth century.

***

I love putting out Chartbook for free to a wide and diverse range of subscribers from all over the world. It is a pleasure to write and a great place to pull ideas together. It is also, however, a lot of work. If you feel moved to support the project, there are three subscription options:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.