Like it or not, we live under the shadow of China. First there was the “China shock” to labour markets which has – whatever its actual size – become a cause célèbre in the US. Then there was the fear of a Chinese financial attack – the idea of a balance of financial terror between the US and China. In 2008 that failed to materialize. In 2015 the tremors of the Shanghai meltdown were felt around the world. That has come back to haunt us in 2021 with the Evergrande crisis. Since 2020 we have been battling with COVID – contagion from China in the literal sense. In 2021 America’s military leaders had their “almost Sputnik” moment with the news of China’s hypersonic tests. Finally, in the second half of 2021 Europe has been reeling from a shock to energy markets which originated in China.

China’s dramatic recovery from the COVID shock and the inability of energy supplies to keep up, has delivered a dramatic jolt to global gas prices. As far as Europe is concerned, it is the most severe energy price shock since the 1970s.

Source: Trading Economics

In Europe the supply pressures are so intense that nuclear-reliant France has resorted to burning oil to keep the lights on.

The energy price hike has triggered a series of debates about the future of the energy system, the impact of the green transition etc. I was involved in exchanges with Richard Seymour and Cédirc Durand and others. In this post I want to go back to the beginning.

This starts with China and it starts with coal. It is by way of coal that we get to gas and, by way of gas, we get to Europe.

***

To be precise (correcting and amplifying a briefer treatment in Chartbook #51), the story starts not with supply shortages, but with a huge surge in energy demand.

As energy consultant Wood Mackenzie reported in awe: “China’s economic growth at over 8% in 2021 fired up soaring power demand: China’s electricity consumption grew by 10%, which was the fastest annual growth for any major economy in the recorded history of the industry.”

Not only electricity generation but steelmaking and cement all came on stream in force in early 2021 driving up energy and coal demand. Any supply system would have had a hard time keeping up with such a rebound. China’s could not. The IEA’s Coal Report for 2021, released in December gives a blow by blow account.

It starts by setting the scene in suitably grand style:

Power generation in China alone is responsible for almost one-third of global coal consumption. No other sector in any other country – or any other fuel – has a comparable influence on global trends.

Unlike in the rest of the world on account of its rapid recovery from COVID, power demand in China rose even in 2020 by 2.2%. That was less than the trend 3.9% per annum growth, but already over the winter of 2020-21 difficulties were apparent.

An unusually cold winter further increased electricity and heat demand. A large share of China’s coal-fired power capacity is co-generation (combined heat and power production) … Therefore, as demand spiked to meet higher-than-usual heating needs in December 2020, China was confronted with power shortages due to inadequate capacity in at least five regions.

Then in the summer a heatwave intensified cooling demand at the same time as low rainfall amounts reduced hydropower generation. By the third quarter of 2021 a severe imbalance had emerged between coal supply and demand with order books for coal mines lengthening alarmingly.

Why could China’s coal production not keep up? Did environmental concerns, and specifically climate policy, contribute to the inelasticity of supply?

The short answer is that China’s giant coal industry is undergoing restructuring. The reshuffling of production from small to large mines and between regions is dramatic. Environmental concerns are a major issue for the governance of the sector and in the 14th Five-Year Plan, climate is a concern too. But to the chagrin of climate campaigners everywhere, we are far from the point at which climate is the chief regulating factor in China’s coal production (energy demand, as we shall see, is another story). As the IEA summarizes the situation:

“Under China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2015-2020), about 5 500 coal mines with a total production capacity of ~1 000 Mtpa were closed, reducing the total number of mines to 4 700. New modern, large-scale opencast and underground mines are being approved to replace this capacity, mostly in the main coal mining regions of Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Shanxi and Xinjiang. In 2020, coal production increased 1.1% to a new high of 3 764 Mt, surpassing the previous record set in 2013. Although the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted China’s coal production in the first quarter of 2020 (despite a production capacity expansion), it has been climbing since the second quarter.”

The 14th Five-Year Plan, which outlines China’s economic priorities for development during 2021-2025, attempts to balance environmental (i.e. climate), energy security and affordability considerations. Therefore, despite China’s commitment to peak its carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, the plan considers coal an irreplaceable energy source in upcoming years. The plan’s aim is to stabilise coal production to secure 4 100 Mt by 2025.7 … Following the direction already charted by the 13th Five-Year Plan, Chinese mining companies are to make their mines increasingly safe, automated and digitalised, as per the “large-scale, modernisation, intensification and ecology” development directive. As part of this process, China’s total number of mines is to be reduced by 700 to 4 000, meaning that small mines will continue to be closed. The government of Shanxi, currently the largest coal-producing province, has already announced a production cap of 1 000 Mt per year. Meanwhile, production increases are planned for Inner Mongolia’s Shendong Coal Basin, and for mines in Shaanxi and Xinjiang. Total coal production of 3 982 Mt is forecast for 2024.

As the IEA coyly notes: “we do not expect (unabated) coal consumption and production to be on the Net Zero by 2050 pathway by 2024.”

Inner Mongolia is favored because it offers the prospect of developing gigantic opencast mines.

The problem in 2021 was not so much the inadequate size of the coal mining capacity in China, as the sudden surge in demand and a series of specific supply difficulties impacting the main four producing regions in China.

Starting in 2020, Inner Mongolia’s coal supply growth was hampered by an anti-corruption probe that strengthened control of mine production for approved capacities. Safety and environmental regulations also became stricter throughout the country and punishments for failing to comply with safety guidelines were increased. These factors, together with natural disasters such as floods, disrupted China’s coal production and logistics in 2021 …

… thermal coal production decreased and coal transports to coastal provinces were delayed by heavy rainfalls and flooding in North China in July, August and October 2021. Furthermore, following a series of accidents, safety regulations were tightened and mining operations were interrupted more frequently for safety reasons….

… In October, flooding in Shanxi forced mines to shut down and made the supply situation even worse just as northeastern China’s heating season was beginning.

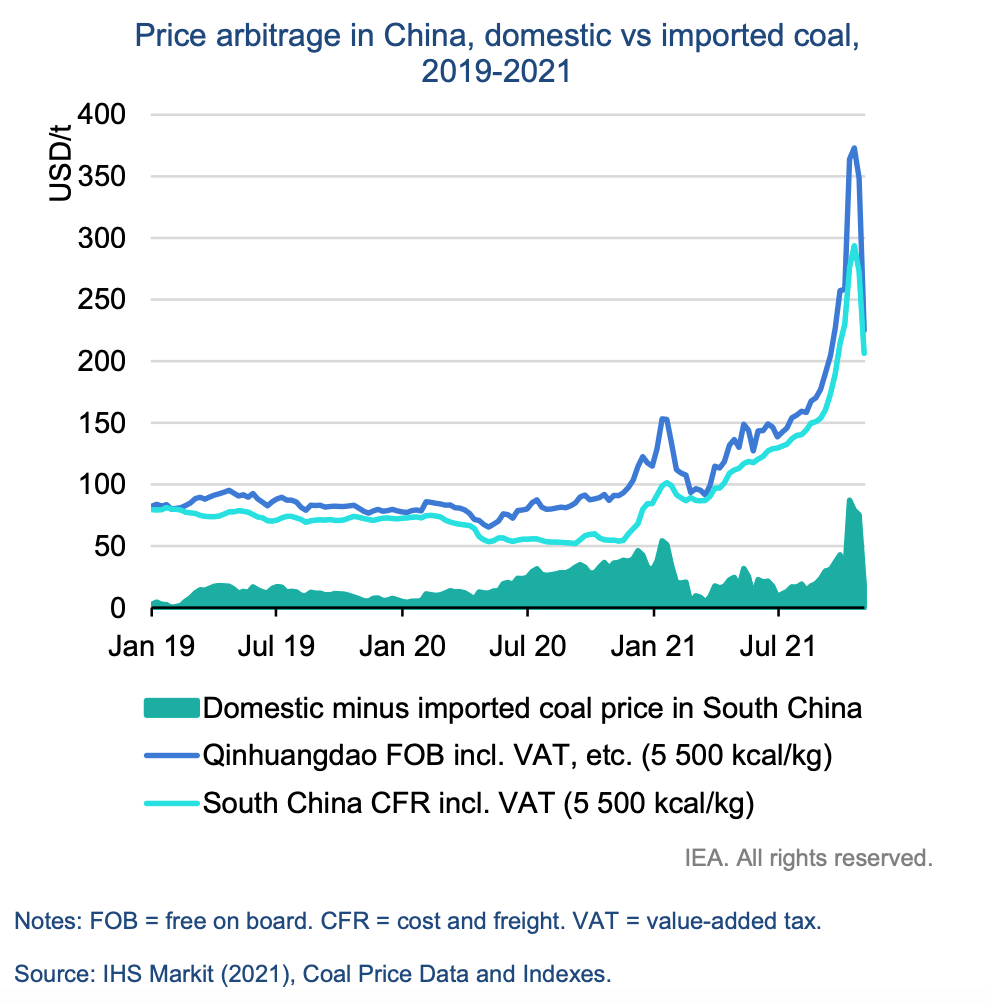

One relief valve for China’s stressed coal supplies could have been imports. But Beijing pursues a deliberate policy of throttling the import of coal. China sets an annual import quota, which is a carefully kept secret. This restriction of imports has resulted in a spread between higher domestic coal prices in China and lower prices available on global markets.

… In January 2021, the price spread jumped to USD 54/t due to high domestic coal demand for power generation as well as heating during an exceptionally cold winter in China. Shortly afterwards, however, the domestic coal price fell sharply and the price spread shrank to USD 4/t as demand decreased with milder temperatures and the Chinese New Year holidays in February. In the second quarter of 2021, both Chinese domestic and international coal prices rose again, and in mid-October the price spread spiked at USD 87/t, a relative premium of about 30%. This price spread signals arbitrage opportunities for Chinese traders, but they were not able to exploit them due to China’s import restrictions.

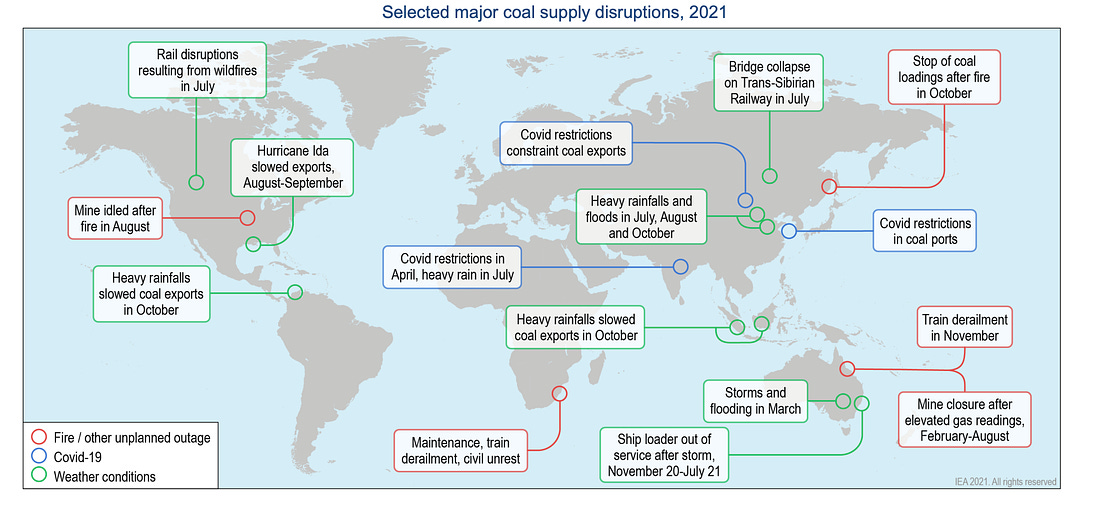

In 2021 even if China had wanted to source a large volume of imports, global supplies were restricted, not by strategic climate policy, but, once again, by a variety of short-term factors.

Coking coal imports from Mongolia, already low due to pandemic containment measures, were suspended for a week in August after several truck drivers tested positive for Covid-19. Plus, Chinese ports require foreign ships to quarantine for 7 to 21 days, and some ports have also been partially or fully shut down, delaying ship loading and unloading and raising coal freight rates in Asia. Indonesian coal exporters have not been able to fill China’s supply gap. Heavy rainfalls in the coal-rich regions of Kalimantan and Sumatra constrained coal production in 2021 and even forced several producers to declare force majeure in the third quarter of the year. Low heavy-equipment availability also limited the ramping up of coal production, so to secure the country’s own domestic supply, Indonesian authorities called for compliance of domestic market obligations for more than 30 mining companies to limit coal exports. This intensified supply scarcity in East Asian seaborne coal markets and drove prices up in August and September 2021.

The IEA has mapped outages and disruptions to global coal supplies. It was a perfect storm.

Back in China, as coal prices surged, in a well-functioning market, electricity generators would have passed those price increases on to consumers, raising the profit margins of generators, thus encouraging extra capacity to come on line, and throttling unnecessary demand. But China’s giant electricity market (like that of India) is only partially liberalized. As Caixin reports:

Although China has launched several rounds of restructuring to liberalize the power market since 2015, only 30% of electricity supplies are priced by market forces, the rest being under government control …. (end-user electricity prices are fixed and may fluctuate by no more than 10 percent.) … In Guangdong, a power plant staffer said generators were selling below cost when the coal price reached 1,400 yuan per ton. Thermal coal prices in the Guangzhou port hit 1,550 yuan a ton on Sept. 24, up 310% from a year earlier. Squeezed by rising costs, several leading power generators in August sent a joint letter to the Beijing Municipal Commission of urban management asking for higher prices on electricity purchase contracts for the fourth quarter. The companies said almost all coal-fired power plants were suffering losses. But signs of change have emerged as several provinces, including Shanghai, Shandong and Guangdong, have allowed greater fluctuation in local power pricing.

Given the seriousness of the energy supply situation, Beijing might have resorted to emergency liberalization measures, but it was more concerned with inflation so the price caps remained in place. The net effect is that unconstrained demand met reluctant supply. This generates headlines about an “energy crisis”. Fingers are pointed at the coal mines, but the problem is not in coal supply but in the power market. Lauri Myllyvirta gives a particularly penetrating account of China’s energy market failure in this piece in Foreign Policy. As he makes clear, it was not environmental concerns, but perverse incentives that created the electricity supply crisis. It was not until October that Beijing permitted a general liberalization of electricity prices, which brought generators back on line.

In the short-term, the immediate response of the the authorities was to ration power supply.

In mid-2021, China began to curtail industrial activity in some provinces as coal supplies and imports were unable to keep up with demand. In September, power rationing for industrial consumers occurred in 20 provinces. In Guangdong province, for example, manufacturers of ceramic products experienced power cuts of up to 70%, and Yunnan province ordered cement producers to cut production by 80%. Similar measures – and even complete power cuts – affected aluminium, steel and other energy-intensive industries all over China. In Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning, even residential consumers were affected as power supplies fell short of demand by as much as 20% at times.

It was at this point that climate concerns entered into the picture, not on the supply but on the demand side. To begin limiting emissions Beijing has decreed targets for energy consumption and energy intensity – the policy of so-called “dual control”. As regions exceed their targets they are red-flagged and at that point they begin to cut off industrial consumers who have exceeded their quota.

By halfway through the year, ten provinces – accounting for around 40% of China’s GDP – had reached the “red” warning level for either energy intensity or energy consumption. The red level is a first-level warning when implementation is more than 10% off the target. The yellow level indicates that implementation is below the target, but lower than 10%. Towards the end of the third quarter (end September), some provincial governments were forced to mandate power cuts to energy-intensive industries to achieve their quarterly targets.

In this way, climate policy considerations enter the picture of the Chinese energy crisis. But whether one can really call this a crisis or even a dilemma, as some authors have suggested, is debatable. China has a target for energy consumption and it is imposing it. The crisis is not at the level of policy. The policy’s objectives are being met. The crisis arises at the level of the firms that find themselves without power and realize, abruptly, that their business model is not viable. That in turn creates a dilemma in the form of laid off workers and paused production.

All told, by September two thirds of provinces in China were under one or other form of energy rationing, whether due to excess demand or inadequate supply.

The resolution in the short-run was for Beijing to drive up coal production.

To ease the supply shortage, the Chinese government has asked regional authorities and coal mining companies to boost coal production. At the same time, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has called on major producers to cap prices on a voluntary basis (rail availability will be limited for producers pricing above the cap) … authorities in Inner Mongolia approved the restart of 38 disused opencast mines with a capacity of 66.7 Mtpa, and the NDRC has eased conditions for mine extensions taking place before April 2022. In addition, Shanxi province ordered its 98 coal mines to increase their annual output by 55.3 Mt over the remainder of the year and allowed 51 coal mines that had reached their annual production cap to keep producing and raise capacity, adding roughly 20 Mt of extra supply.

In the long-run the answer is greater efficiency, decarbonization, or structural change.

In 2021 the headlines were grabbed by the crisis at Evergrande and Beijing’s policy of deliberately deflating the real estate bubble. As far as the energy and emissions questions are concerned, this is crucial. The IEA reports: “China’s steel and cement production declined considerably. In September 2021, cement production was 13% below the 2019 level and steel production was 21% lower.” A shift away from the construction-driven, heavy industrial growth model is clearly essential if China is to achieve its decarbonization goals. Again, Lauri Myllyvirta is a crucial follow on this. Read his report on the downturn in China’s real estate sector and its impact on emissions.

As Caixin’s reporting makes clear, the structural adjustment is wide-ranging.

In late September, Zhejiang’s energy bureau said the province is determined to replace some energy-intensive industries with new businesses. The eight industries with the greatest demands for energy, including textile and dyeing, account for 43% of the province’s power consumption but contribute only 13% of economic output, according to the bureau. Zhejiang’s textile manufacturers enjoyed a spike in overseas orders this year as production remained largely halted in India and Southeast Asia because of the pandemic. Many companies quickly expanded production capacity to accommodate the rising orders, one industry expert said. But profit margins in the industry have become thinner, squeezed by soaring material and shipping costs. …. With high energy consumption and little profit margin, China’s competitive edge in textiles will keep shrinking, and the industry will continue relocating to Southeast Asia, said Wu Xinyang, an analyst at CSC Financial. China’s energy-control ambitions will also affect its steel industry, the world’s largest in terms of output since 1996. According to China International Capital Corp., the 19 provinces blacklisted by the NDRC for failing to fulfill energy-control targets account for 53% of the country’s total steel output. In Jiangsu, steel mills were hit by the toughest production-halt orders in September. A company executive told Caixin that his plant was ordered to suspend operations on Sept. 11 for more than two weeks. “I’ve never seen a production halt last for so long,” the executive said. He predicted that more such orders may come in October. A manager at the Anshan Iron and Steel Group in Liaoning said the production restrictions will force steel companies to shift to more-advanced products … Although China has remained the world’s largest steel producer for more than two decades, it still relies on imports for some highly sophisticated steel products. Under the pressure of energy targets and capacity cuts, China’s raw steel output declined 13.2% in August to 83.2 million tons. The central government has taken moves to force local economic transformation. Since June, it has turned down several local authorities’ proposals to build new facilities with high energy demand, including a 126 billion yuan coal chemical project in the northwest province of Shaanxi, which was supposed to the largest of its kind in the world.

All told these adjustments have been enough to end the acute phase of the energy crisis in China. By November, energy rationing was easing. But this action was not enough to prevent spillover from China’s energy crunch to global markets. The most important of these is gas. In 2021 it was through the gas market that the imbalance of demand and supply for energy in China spilled over to world markets.

***

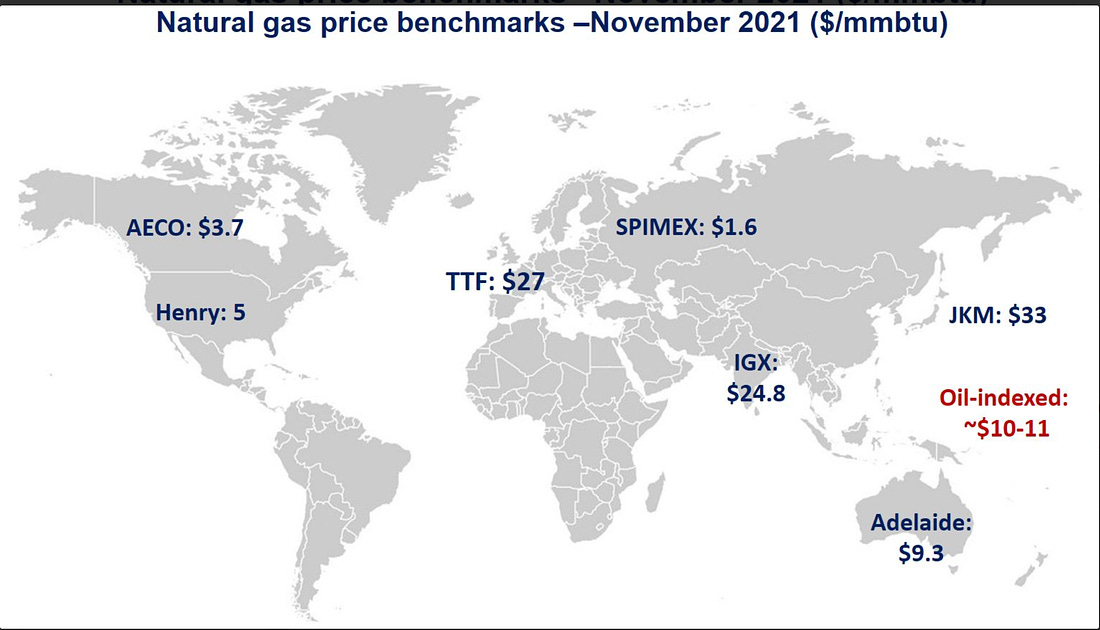

Unlike oil, given the difficulty of transport, the global integration of gas markets is only partial. Despite the effort to expand gas exports in the form of LNG, the US gas market is still largely insulated from that in the rest of the world. LNG accounts for only 10 percent of production. As a result America’s gas market remained largely insulated from the China shock. Unlike for oil there is not “one big market” for global gas.

Global discrepancy in benchmark LNG prices

Source: Global LNG Hub

The globally traded LNG market has long been dominated by Asia. Japan, unable to import gas by pipeline, pioneered the LNG market. The first LNG shipment to Japan arrived in November 1969 on the Polar Alaska.

Today, China is increasingly driving the gas market.

Gas has moved to the center of China’s energy strategy as it contemplates the transition away from coal. In 2020 gas-fired power generation accounted for only 3.5% of China’s electricity supply. There is, thus, huge scope for growth.

As Wood Mackenzie reports: “The national oil companies (NOCs) have discovered 6.85 trillion cubic metres of natural gas resources in the past decade, 45% of total incremental resources since the founding of the People’s Republic of China.”

Historically, gas use in China has been dominated by the the industrial sector (as fuel and feedstock), with the industrial share of consumption at 50% of the market. But coal-to-gas switching in power generation is shifting the balance. “Residential, commercial and space heating (RCH) demand is fast catching up. Coal-to-gas switching in RCH has already magnified China’s winter demand peaks. The trends of urbanisation, higher affordability, gas distributors building new city gas projects and winter clean heating requirements will provide gas access to a broader population.”

To reduce pollution particularly around Beijing, China pushed a campaign in 2017-8 to convert millions of homes from coal to gas heating. The result was a sudden shortage in gas supplies and LNG bottlenecks. Undeterred, in October 2020, China launched a new high-profile campaign to shift 7 million households from coal to gas heating over the winter of 2020-2021.

In 2021, China’s demand for gas surged even more dramatically than that for coal. “In H1 2021, China’s gas demand saw a 16% year-on-year increase, led by strong power and industrial demand. Underperforming hydropower in southwest China, tight coal supply coupled with high coal prices across the country, and high summer temperatures supported gas-fired power generation. Export-led economic growth and domestic consumption recovery benefited overall energy demand, including natural gas. … To meet its rising demand, China has been boosting domestic production of natural gas, debottle-necking infrastructure, diversifying import sources and introducing market-oriented reforms.”

Unusually, China’s LNG imports rose in Q2 2021, normally a slow period for global markets.

In 2020, China was already the world’s largest gas importer. In 2020 it imported 48 billion cubic meters through pipelines and 93 billion cubic meters in the form of LNG (67 million tonnes (Mt)). In the first half of 2021 China overtook Japan as the world’s largest LNG importer.

LNG has certain key advantages for China. Until piped gas storage capacity is expanded, LNG is more flexible than pipeline gas and it is particularly attractive in Southern China, which is far from the main onshore gas-producing basins.

To meet this demand, investment has been gigantic. In China the gas infrastructure is taking shape:

A crucial landmark was the establishment of China Oil & Gas Pipeline Network Corporation (PipeChina) in December 2019. The new national pipeline company will be responsible for the development and management of transportation of gas, crude oil, refined products plus re-gasification and underground gas storage. PipeChina will consolidate a large part of midstream assets held by the three national oil companies (NOCs), which have started to swap some assets. It will operate the infrastructure assets as an independent business and will provide efficient third-party access, facilitating market access to suppliers and end consumers.

The problem is that lead times are long. LNG and other gas projects are very complex. Investment in storage capacity in Asia is even more inadequate than in Europe. As a result, supply capacity was not sufficient to meet the sudden demand spike in 2021. Prices surged.

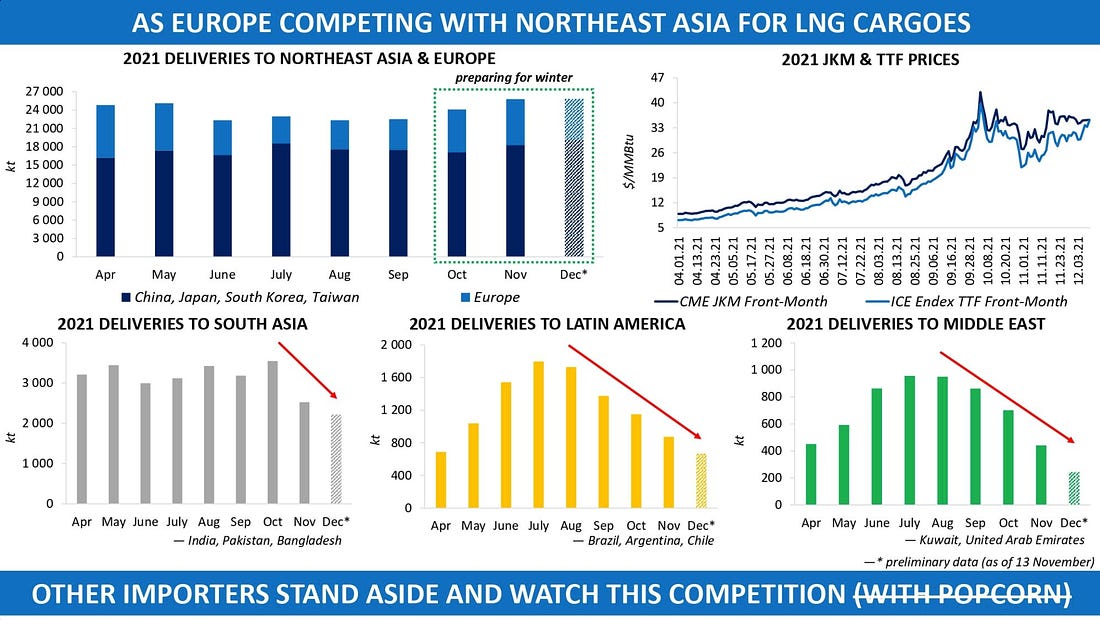

Whilst US natural gas prices languished in Asia gas prices surged to historic highs. European gas prices followed. By December Asia was so glutted with LNG and Europe was so desperate, that cargos were being diverted en route and Asian buyers considered re-exporting their LNG to Europe. Europe’s energy future has come to hang on how cold the winter weather will be in Asia.

Source: Global LNG Hub

For more than a decade, Europe has been relying on imports of cheap gas, whether by pipeline or in the form of LNG priced at spot rates. It has been a buyer’s market. Apparently no one considered the possibility that the global pattern of demand might be about to shift. No one considered the need to build adequate stocks of gas. In 2021 the tables turned. The China gas shock arrived.

***

The 2021 energy price shock is not primarily a story about inadequate supply. It is the story of a huge demand surge and a breakdown in China’s ramshackle electricity markets. Throwing government mandated shutdowns into the same pot as energy supply problems triggered by faulty electricity pricing, attributing either to inadequate supplies of coal, or the overshadowing of the coal sector by decarbonization, simply muddies the water.

But what is clear is that China’s energy system is the whale in the global energy economy. It is the dominant factor in the emissions equation as well. As its shifts balance away from coal that will affect other energy consumers all around the world, above all consumers of gas. As Europe is learning, if you rely on the global gas market, you are relying on a market increasingly driven by Chinese demand.

It is not even obvious, in fact, what role gas will play in China’s energy transition. The uncertainty of supply over recent years, gives Beijing reason for caution. Coal dominates the equation and renewables may expand so rapidly that gas never plays the central role that it does in Europe and the US today. Given the speed with which transition must be accomplished, the idea of gas as a transition fuel may prove a snare. China’s official documents are hard for outsiders to read and a debate is ongoing within China itself.

But the point is that even with gas accounting for a small part of China’s energy mix, even with coal as its mainstay, China’s development has huge implications for the rest of the world. If that is what we mean by an energy dilemma, then there is certainly a dilemma. Except, of course, that a dilemma implies a tough choice and with regard to energy policy that is hardly the case. Both China and Europe need to force investment in renewables and the development of storage technology at the fastest rate possible. That is win-win. It creates jobs. It will generate profit. It increases resilience. It reduces dependence on fickle global markets. The problem is not inadequate investment in fossil fuels, the problem is inadequate investment in the alternatives.

***

I love putting out Chartbook for free to a wide and diverse range of subscribers from all over the world. It is a pleasure to write and a great place to pull ideas together. It is also, however, a lot of work. If you feel moved to support the project, there are three subscription options:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.