It has been another week in which economic history has been made. On the heels of the trade wars and the mounting geopolitical tension between the US and China that marked 2017-2019, the shock to the dollar-based global financial system delivered by the corona crisis poses a fundamental challenge to economic globalization as we have known it.

The operation of the global economy was, in any case, undergoing change. As I argue in this new piece in Foreign Policy the days of the Washington consensus are long behind us. The relative positions of the US, China and International Financial Institutions like the IMF have undergone major shifts in recent years. But the collapse in confidence, the unprecedented sudden stop in real economic activity and the dislocation of 2020 are adding an extreme urgency to these changes. The question now is how the world economy will be put back together again.

Faced with the immediate crisis there is an intense burst of debate going on about the problem of securing dollar funding for the world economy. This is the second of two round ups. Round one is here.

This essay in Bloomberg by Chris Anstey and Enda Curran offered an excellent historical retrospect on the dollar question. They make the important point that back in 2009 China and then in 2010 Korea proposed that the question of the world economy’s dependence on dollars should be addressed, only to be stymied.

Matt Klein is back from parental leave at Barrons. It is great to have him as part of the discussion. On his return his first column focused on the dollar-funding issue.

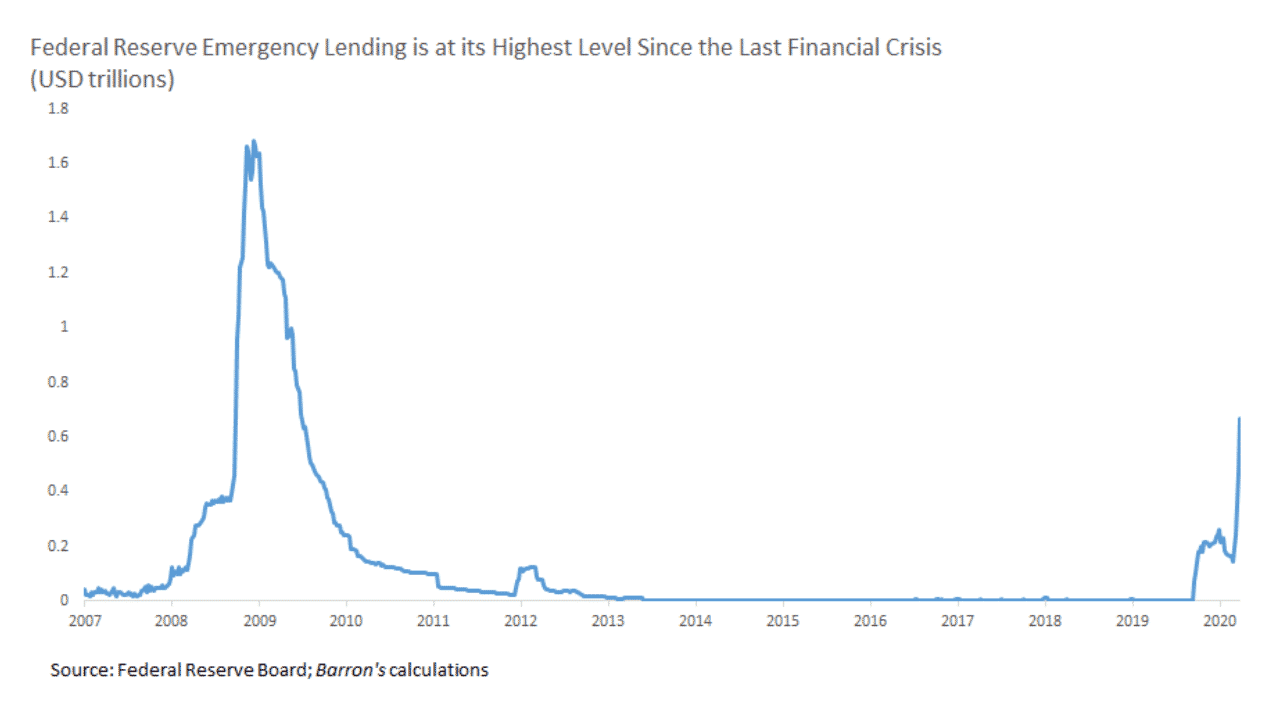

To feed dollars into the stressed global financial system, central bank liquidity swap lines have been activated and dollars have begun to flow through them. We can actually map that flow more or less in real time through the regular weekly balance sheet data of the major central banks. The Fed released numbers this week which show how sums outstanding have surged. Matt provides this striking graph.

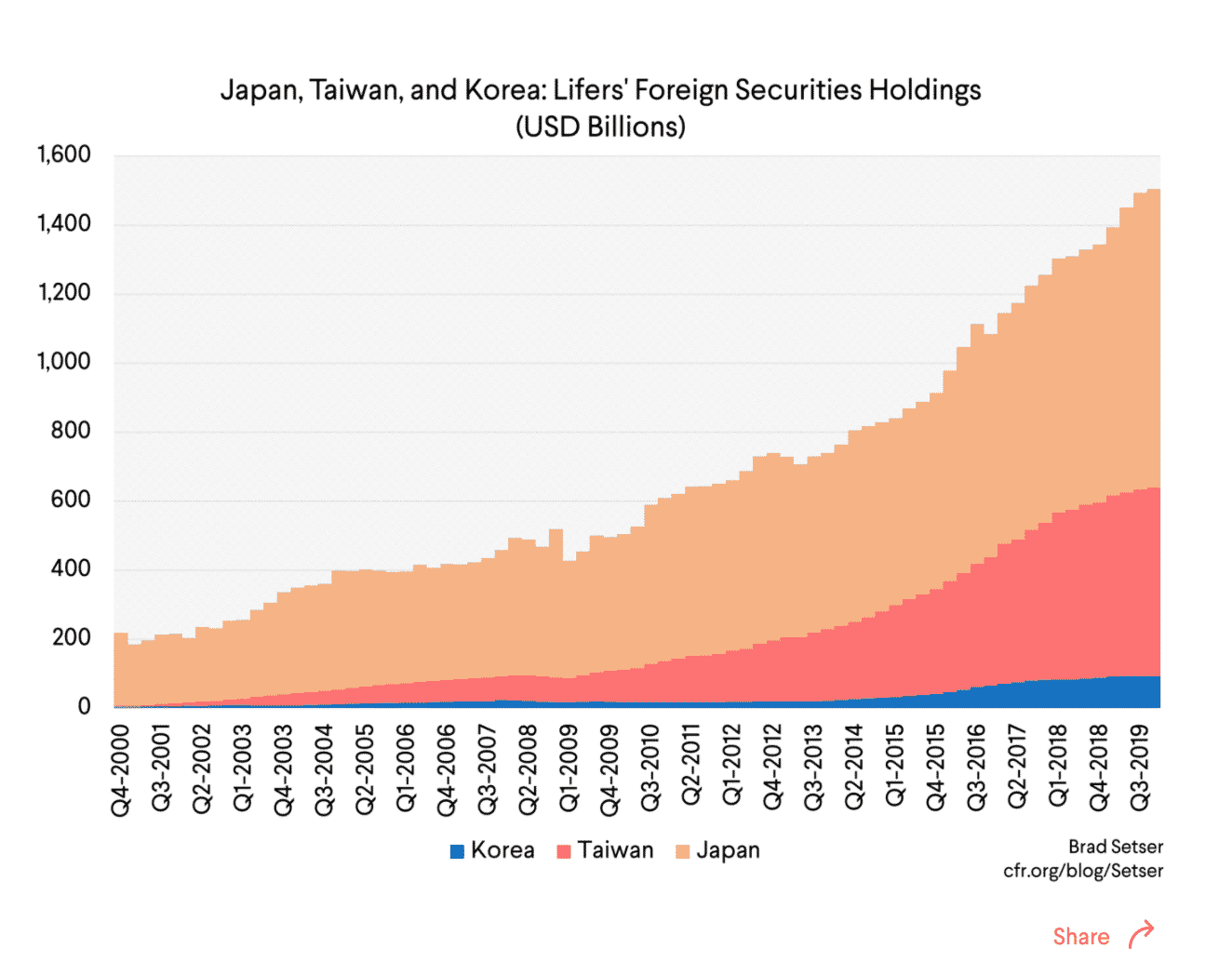

At Alphaville Claire Jones worked the BIS numbers and highlighted the fact that the global imbalances in dollar funding are highly concentrated in the advance economies and Japan in particular was under pressure. That is probably why the swap lines were activated so urgently. The aim was to ease the disruption in US asset markets as Asian investors made urgent sales.

South Korea was one of the real tell-tale crisis cases in 2008. This year, in early March, signs of funding difficulties have reemerged, as noted by this smart piece by Andy Mukherjee They have since been eased.

To really dig into the financial situation of the major Asian investors, Brad Setser is an essential read. On his CFR blog he outlines the stresses on the life insurers who hold $1.5 trillion in US bonds, including corporate bonds that have lost valued. Furthermore, these holdings normally need to be hedged against exchange risk.

Brad argues that though the scale of this financial entanglement is alarming in its dimensions, it can be handled by Asian governments leverage their large forex reserves to provide foreign exchange cover and the investors riding out the storm.

As Brad also points out in one of his brilliant twitter threads, the surge in the dollar may cause generalized pressure, but its impact varies according to the particular use to which dollar funding is put. There is not one world of dollar funding. There are many. This is beautifully anatomized in the work of Iñaki Aldasoro and Torsten Ehlers of the BIS. There are huge differences between Mexico where a large part of dollar funding is made up of bonds issued by non-financial corporations and Turkey where the is a remarkable reliance on bank-based funding.

.

.

How to respond to this landscape of pressure points, was the gist both of my pieces both in the New York Times and in Foreign Policy.

In the FT Raghuram Rajan, ex of the Reserver Bank of India, threw his weight behind the calls for coordinated action to support emerging market economies in the face of the crisis.

Today Augustin Carstens, ex of the Bank of Mexico now of the BIS, points out the need to tailor dollar-liquidity provision to a crisis that is not being driven by problems in bank balance sheets. This is not a rerun of 2008. The plumbing needs to be extended.

Clearly, national economies and business interests vary greatly in their funding needs.

China has huge reserves and impressive governmental capacity but the sheer scale of the financial obligations of its corporations is, nevertheless, daunting. Can they really keep all the balls in the air?

Indonesia has been under intense financial pressure. Its corporates are highly exposed. The virus is spreading fast and is forcing a lockdown of the sprawling metropolis of Jakarta. There are rumors that it asked for a swap line. It did once before, in 2015. It was turned down.

South Africa is perhaps most worrying. Growth was stagnating even before the crisis, well below what is necessary in light of the rapidly growing population. The unemployment situation is disastrous. Last week its sovereign debt lost its last investment grade rating. Eskom, the giant power utility, is a menace both as a power supplier and as a financial liability.

On this and other EM Robin Brooks and his team at the IIF are a vital source:

Source: https://twitter.com/RobinBrooksIIF/status/1244254245634871297

The virus has arrived and South Africa is a country with 7.7 m highly vulnerable people living with HIV. Perhaps not surprisingly, there are rumors this weekend that, for the first time, South Africa is turning to the IMF.

With both the Economist and the FT featuring alarming warning of an impending crisis across the developing world, South Africa will not be the last.