In the US the obsession with the inflation, the Fed, interest rates and financial stability has been displaced from the headlines by an overriding preoccupation with fiscal policy. In the brief interval between the two, Janet Yellen and Jake Sullivan brought the world up to speed on the parameters of what is being dubbed the “new Washington consensus”. More from me on this kaleidoscopic alternation in the FT at the weekend.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the debate about inflation goes on. Culling recent speeches by Philip Lane and Isabel Schnabel results in an interesting composite picture of the distinctive features of both the European and American inflations.

Source: ECB

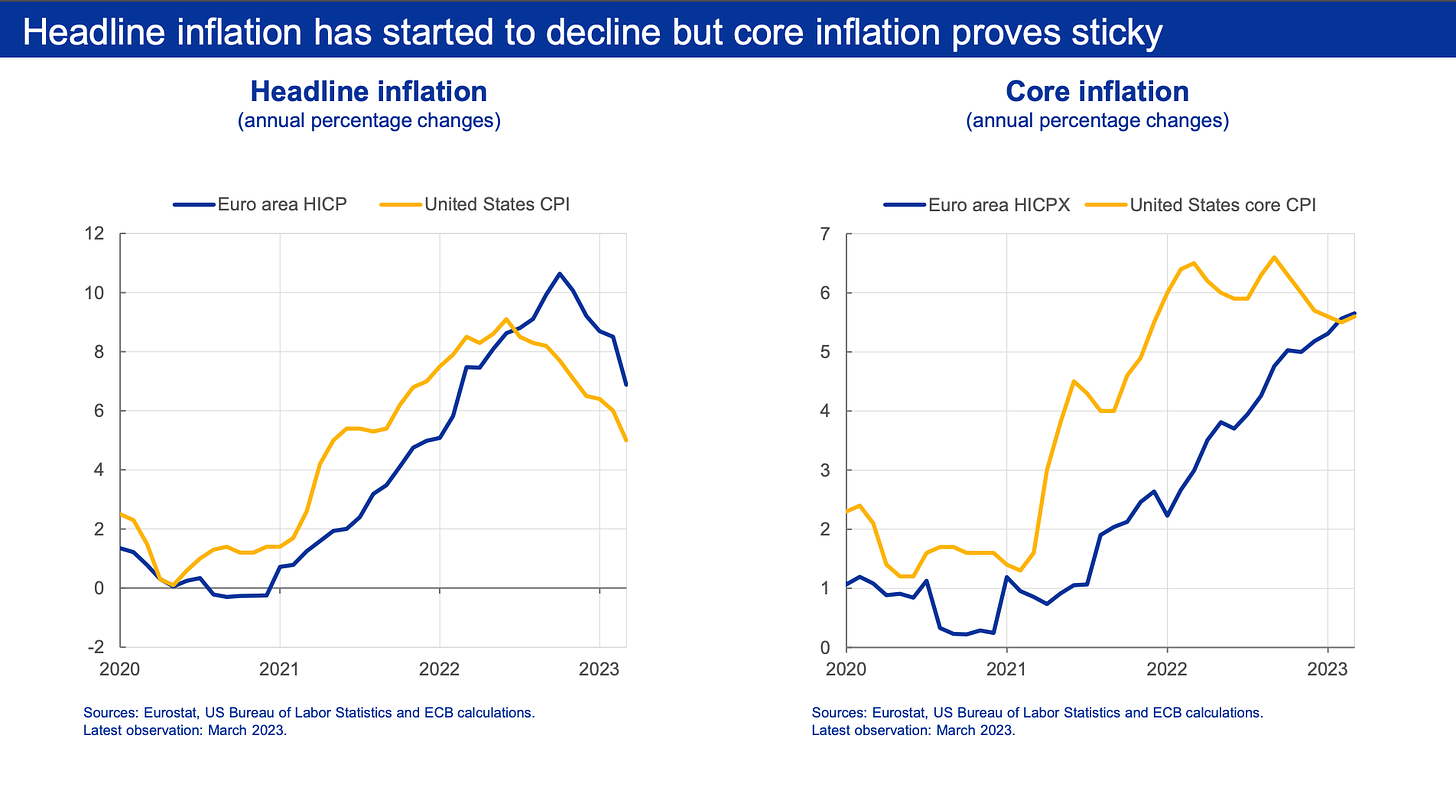

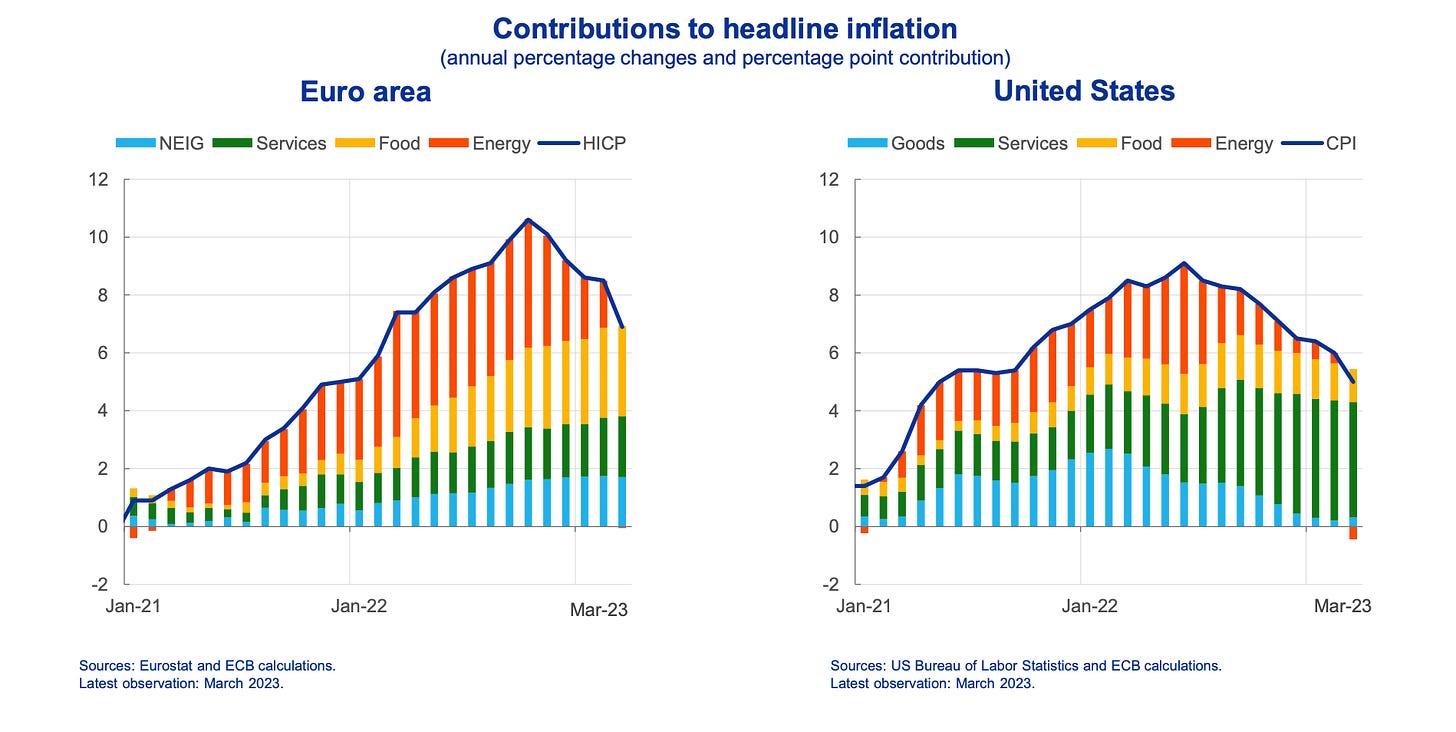

The surge of European inflation past the US peak of 8 percent is largely attributable to the more painful surge in both energy and food prices in Europe.

In the US, by contrast, the acceleration of services inflation has come to dominated the story.

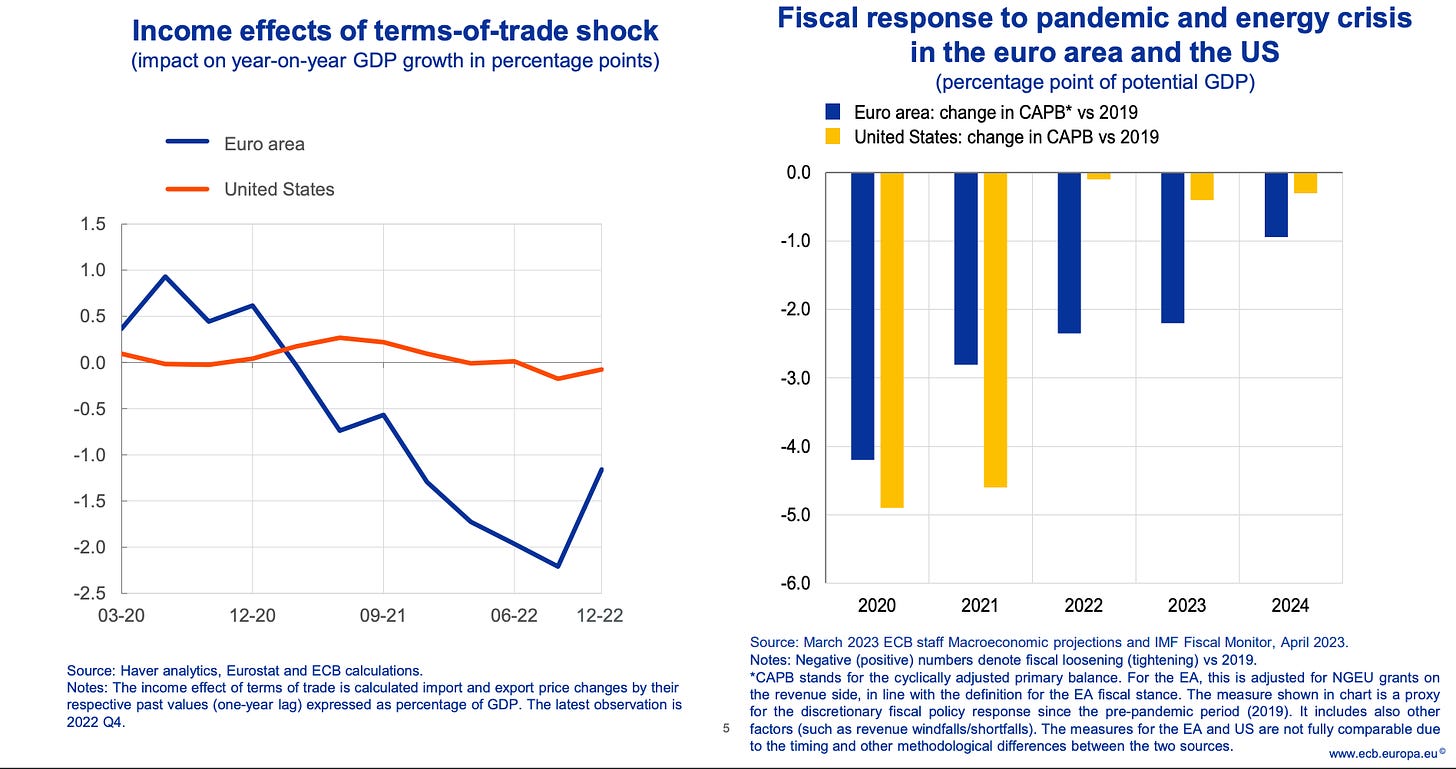

The surge in the prices of imported energy and food inflicted a terms of trade shock on the European economy to the tune of 2 percent of GDP. The impact on the US which is a major exporter of both food and energy was broadly neutral.

Overwhelmingly this terms of trade shock came from energy.

Source: ECB

There is a striking difference between Europe and the US also with regard to the fiscal response to the succession of shocks that hit the world economy between 2020 and 2022. The US fiscal response to COVID was more generous but also contracted more sharply, whereas under the impact of the Ukraine war, the fiscal taps in Europe have remained open.

Whereas the European economy has barely recovered above its 2019 level, the US has clocked up a solid 5 percent growth, driven by a considerable surge in private consumption and particularly the private consumption of goods.

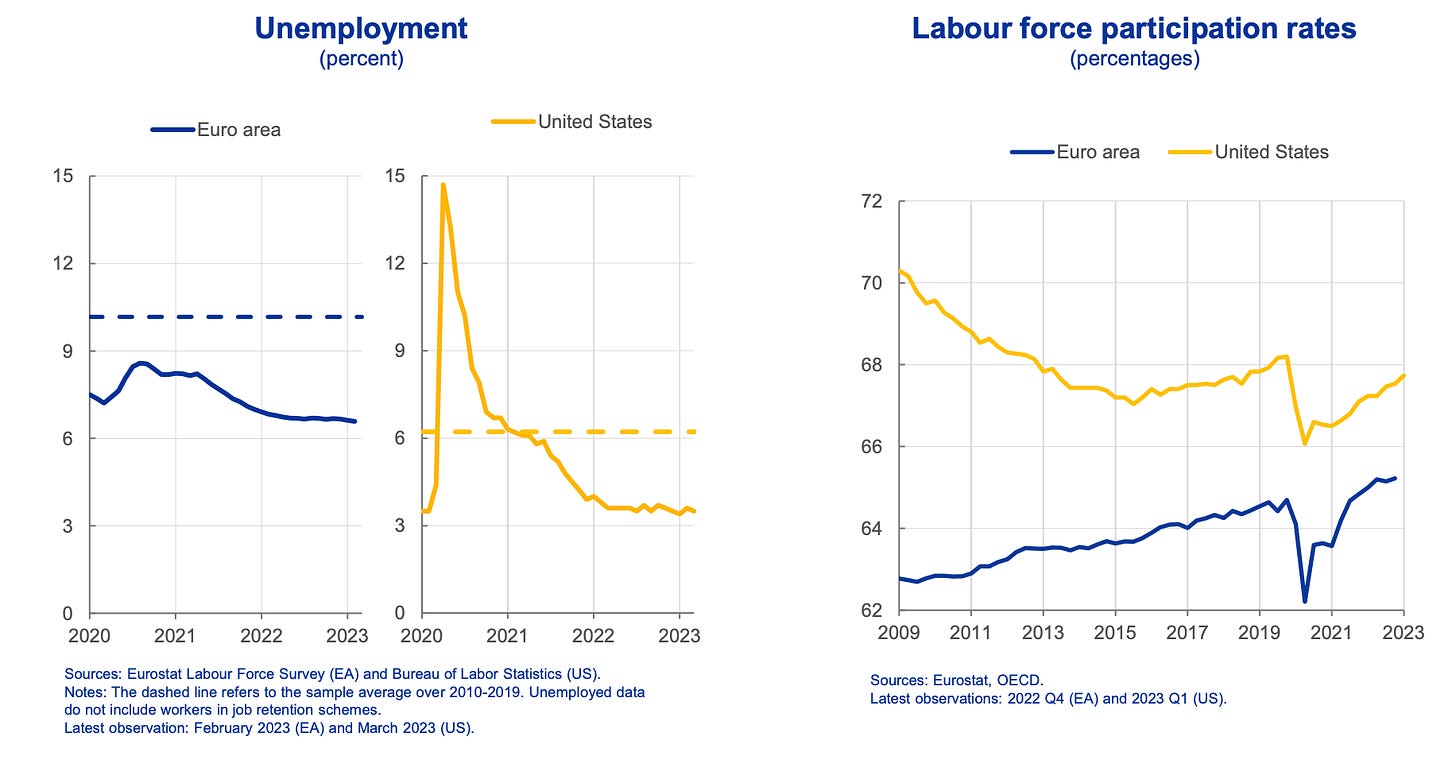

Both in the US and the EU, the recovery from the 2020 shock has produced a strikingly low level of unemployment. But whereas in the EU labour market participation is somewhat higher today than one might have expected on the basis of pre-crisis trends, the US has seen a retreat from the workforce both of younger and older works.

Charts by ABN AMRO bring out the different trajectory of labour market participation in to sharp focus (beware the different scales here).

In both the US and Europe labour market tightness has led to a considerable acceleration in the growth in nominal wages.

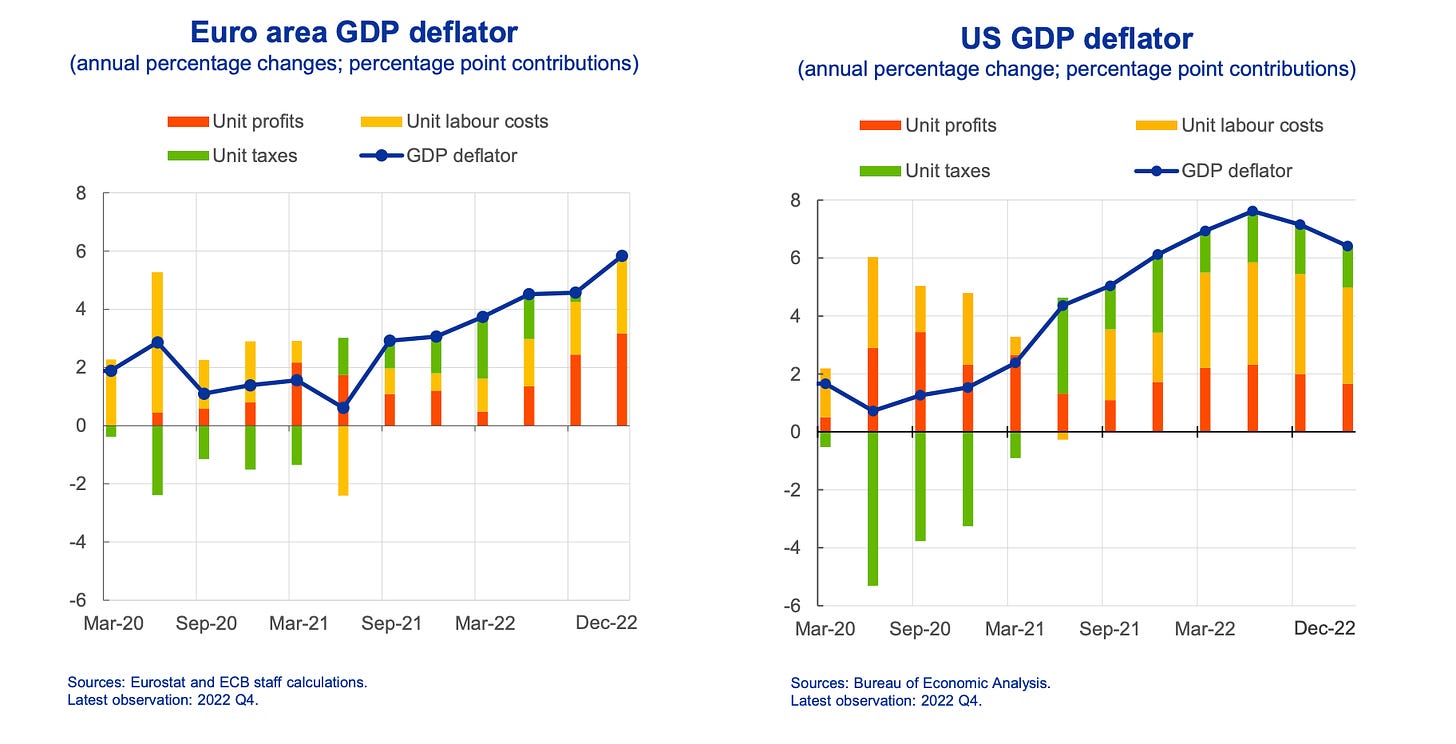

In both cases, nominal wages have struggled to keep up with prices. As a result, if one accepts a cost-push model of pricing, rising unit labour costs can account only for a share of the price increases.

In a striking turn in the public argument, the ECB is willing to credit surging profit margins in Europe with a larger share of inflationary pressure than wages. In the United States, at least according to the ECB’s methodology the lion’s share of cost pressure comes from the size of unit labour costs.

Sectoral data for the euroarea point to construction and agriculture-food as the key sectors for inflation.

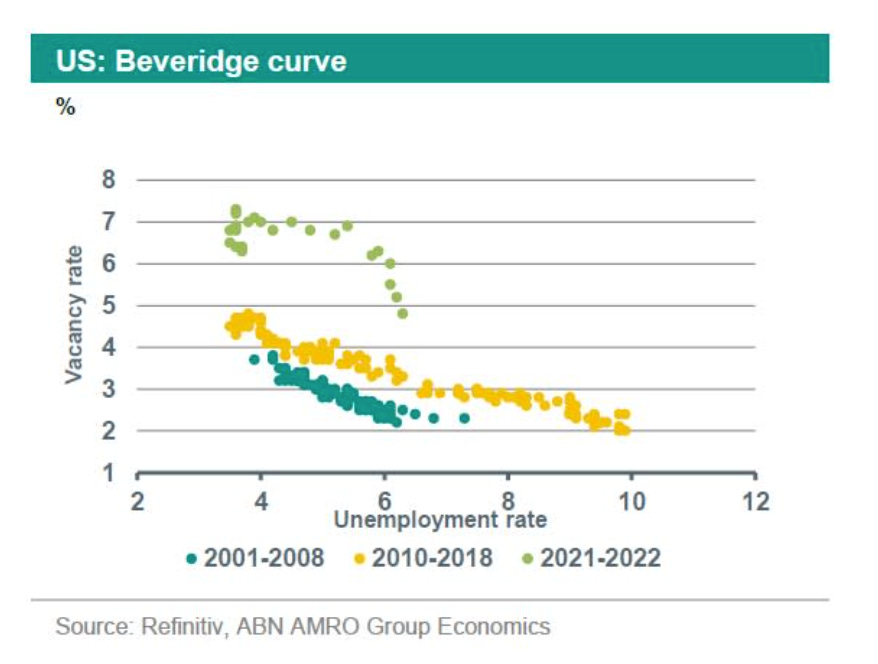

The very different ways in which the labour market shocks delivered by COVID were handled is brought out by a comparison of the Beveridge curves for the US and the Netherlands. In the US the shock is visible in the dislocation of normal relations between vacancies and unemployment. The scale of mismatch in the demand and supply of labour is brought out by the much higher level of vacancies for any given level of unemployment between 2021 and 2022.

By contrast, the Netherlands appears too have absorbed the shock simply by moving along the normal trade off curve. As the economy has bounced back fast from the COVID shock, unemployment has fallen and vacancies are at record levels.

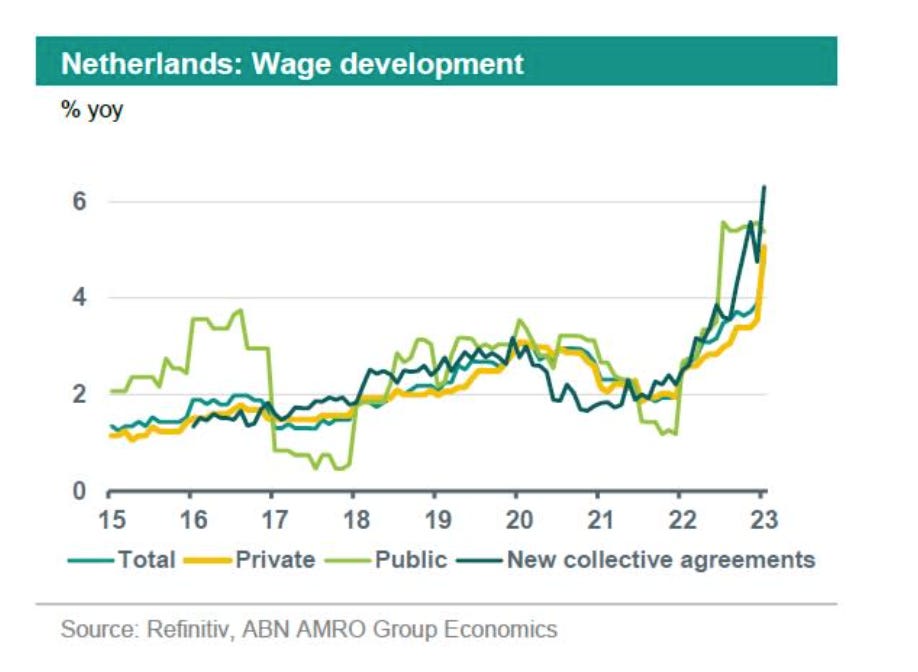

With inflation surging above 14 percent in September 2022 and food prices continuing at rapid pace, it is unsurprising that wage inflation in the Netherlands. is surging as well.

The upshot is that inflationary pressures may have been broadly similar on both sides of the Atlantic, but the underlying dynamics of terms of trade, fiscal policy and labour market dynamics differ in important ways. Currently the Fed is ahead of the ECB in the tightening cycle. Core inflation in Europe is now running ahead of that in the US. Germany may have already turned into recession. But other important parts of the EU economy are still “overheating”. Those wishing to anticipate the future moves of the ECB will be well-advised to track hot spots like the Netherlands.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week