Vogue cover by Salvador Dali December 1946

Christmas trees are BIG business.

Each year approximately 33 to 36 million Christmas trees are produced in North America and 50 to 60 million trees are produced in Europe. In the United States, there are an estimated 15,000 growers, which includes 5,000 choose and cut farms.

Over half of the trees grown in the United States are harvested in only seven counties — three in North Carolina, three in Oregon, and one in Michigan. The top producer, Ashe County in North Carolina, harvested almost two million trees in 2017.

This is a great graphic treatment by Reuters.

As Chastagner and Benson explain, the plantation production of Christmas trees belongs to the era of the “great acceleration” after 1945.

… Although some of the industry pioneers started to grow Norway spruce (Picea abies) and Scot’s pine (Pinus sylvestris) in Christmas tree plantations during the early 1900s, more than 90% of the trees being harvested in the late 1940s were still coming from forest stands. In 1948, the top selling trees were balsam fir (Abies balsamea), Douglas-fir, black (P. mariana) and white spruce (P. glauca), and eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana). These species were readily available from forests. There have been a number of major changes in the Christmas tree industry in the past 40 to 50 years. After World War II, increasing numbers of trees were being planted in plantations and in the late 1940s and early 50s growers started to shear trees to increase their density in response to consumer demands for higher density trees. In the early 1980s some large growers began using helicopters to transport trees from the field to their shipping yard to increase the efficiency of harvest and minimize mechanical damage.

Predictably denser planation production of trees engenders a variety of biological risks.

With the increasing expansion of noble and Fraser fir plantings, growers are facing a number of insect and disease problems including. Balsam twig aphid (Mindarus abietinus), balsam woolly adelgid (Adelges piceae), and the spruce spider mite (Oligonychus ununguis) cause unsightly needle discoloration and/or branch distortion and dieback. When populations are very high, balsam woolly adelgids can also kill Fraser fir trees. The three major diseases that currently limit the production and marketability of noble and Fraser fir Christmas trees are Phytophthora root rot and stem canker, current season needle necrosis (CSNN), and interior needle blight. … Long-term solutions to Phytophthora root rot and CSNN will no doubt come through breeding programs for disease resistance such as those that are underway in North Carolina and the PNW.

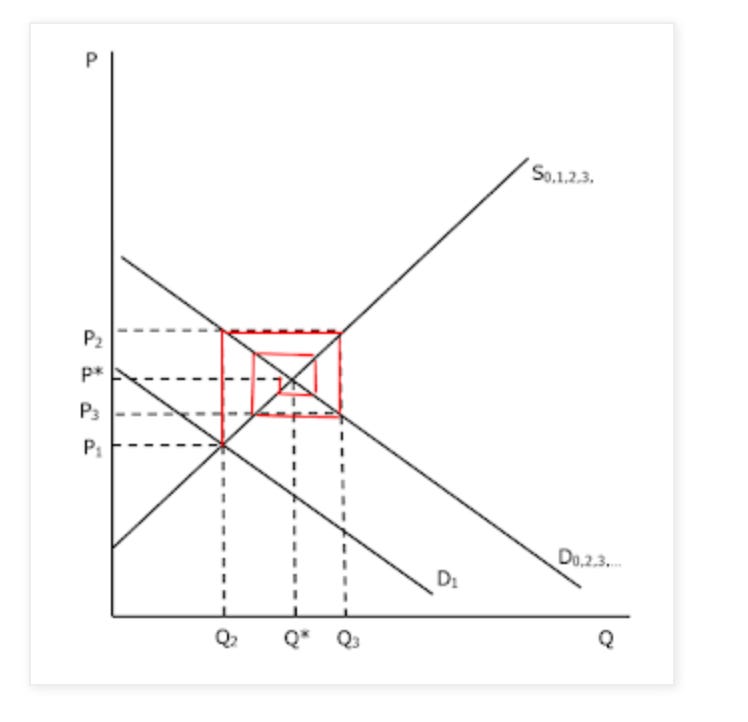

But Christmas tree production is also tricky from an economic point of view. The difficult thing about Christmas trees is that they take so long to grow!

As this excellent piece in The Hustle explains:

A Christmas tree begins its life as a seedling, which is typically purchased from a timber firm like Waverhauser for 50 cents to $1. When the tree is around 2 years old, it graduates from the nursery to the “big leagues” and gets its own 6’x6’ plot of land out in the field. Most Christmas tree farmers aim to plant ~1.2k trees per acre of land. What makes a Christmas tree an unusual crop is its extremely long production cycle: one tree takes 8-10 years to mature to 6 feet. During that time, it’s a financial black hole. “A lot of blood, sweat, and tears goes into growing a Christmas tree,” said Bert Cregg, a horticulture professor at Michigan State University. “You’ve got the cost of land, road construction, tractors, herbicide, fertilizers — and then all the labor it takes to plant and shear the tree.” But even if all goes well, Christmas tree farmers still have to forecast what the market is going to look like 10 years out: Planting too many trees could flood the market; planting too few could cause a shortage. History has shown that the industry is a case study in supply and demand:

- In the 1990s, farmers planted too many Christmas trees. The glut resulted in rock-bottom prices throughout the early 2000s and put many farms out of business.

- During the recession in 2008, ailing farmers planted too few trees. As a result, prices have been much higher since 2016.

If you go back to the early 1980s you find grim warnings about a repeating cycle of overproduction that can be traced back to the beginning of plantation production in the 1950s. See for instance this dark warning from the 32nd Annual Forestry Symposium, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge in 1983:

To look ahead we often need to look back. We need to ask certain questions…. Where are we? How did we get here? And the obvious question that is most important is …. Where are we going? Here in the South we are a new part of a larger Christmas tree industry that has existed for 50 years or more as we know it. Since World War II there has been a dramatic increase in plantation grown trees and a matching decrease in natural stand production. … In the mid-1950’s we had an overproduction of Christmas trees, which was centered in the state of Pennsylvania. This was at that time the plantation-grown Christmas tree center of North America. The center of this production has gradually spread out across the nation, and by the mid-60’s there was a large production area in the Lake States. Between 1965 and 1968 there was an over-supply period that caused great repercussions throughout the industry. Many people abandoned Christmas tree production then as they did in the 50’s. Over—supply and depression in the industry only lasted a few years as it did the first time, and the industry came out of the over—supply period in much better shape as far as the opportunity to profit in the production of Christmas trees. During this time cultural techniques and the quality of production have constantly improved. After the second over-supply period production seemed to spread more throughout the nation, and with the advent of the Virginia pine Christmas tree in the South during the early 70’s we have had a longer than normal period of prosperity in the industry. This prosperity still exists today, but how much longer it will be with us is the question today. There are storm clouds gathering and it appears evident that there will be a recession in our industry, the third since World War II. The success of recent years has bred a surplus in our industry as it has in all other agricultural industries. At the present time it appears that we are planting three to four times as many trees as we are selling. Most of us know this. However, the element of complacency is with us, or what we might call wishful thinking;”

With its 10 year lead times, the Christmas tree industry is a classic illustration of the cobweb model as spelled out in this nice blogpost at Source: Sex, Drugs & Economics

Ten years on from the shock of 2008, the US entered a period of exceptionally high Christmas tree prices, which we are still in today. The worry now is that high prices will cause demand to collapse, which will trigger a crisis in the industry. And who are the culprits? Not Gen Z, who are poor but love their Christmas trees. No, the culprits, inevitably, are “the boomers”!

It is older cohorts who are switching to plastic trees in greater numbers than any other cohort. And spend less than any other cohort on trees too..

Source: Trees.com

Of course, Christmas is not just about producing Christmas trees, the event involves a giant organizational effort at every level of the supply chain, stretching from the Malls of the world, to the factories and workbenches of Asia.

For a remarkable collection of social science articles on “organizing Christmas”, check out this issue of the journal Organization. Here Christmas is given the critical political economy treatment. As Hancock and Rehn write:

Throughout the 20th century the relationship between an increasingly Fordist regime of mass production and consumption, and Christmas, continued unabated. By the 1930s, department stores such as Macy’s in New York and Harrods in London were putting on lavish Christmas displays, while Haddon Sundblom’s iconic images of Santa Claus for the Coca-Cola Company ensured that what has come to be referred to as the ‘Anglo-American Christmas’ began to represent a model of global economic ambition and cultural aspiration. Indeed the increasing significance of Christmas to Western economic performance over the course of the 20th century is no better illustrated than by the acquiescence to business lobbyists by President Roosevelt in the recessionary year of 1939 and his controversial decision to move Thanksgiving in the USA back to the penultimate Thursday of November. This was in order to elongate the Christmas shopping period which traditionally started on Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving.

So much for the economics of the industry. What about the history? Where does the tradition of cutting down and decorating fir trees actually come from?

Again, Chastagner and Benson give a succinct account:

The use of evergreens to decorate homes during winter celebrations dates back to Biblical times. By the 7th century, the pagan custom of using greenery to celebrate the winter solstice became a part of religious Christmas festivities, but it was in the 16th century that Germans in Strasbourg began cutting firs from local forests for display at Christmas. In later years, these trees were decorated with cutout paper flowers, fruits, cakes, tinsel and sugar. By the 18th century, Christmas trees were being decorated with wax candles and by the end of the century decorated Christmas trees could be found throughout Germany (2). Christmas trees were seldom used during the early years of the British Colonies in North America. Although emigrants from northern Europe brought their tradition of displaying Christmas trees during the celebration of Christmas to North America, it wasn’t until Hessian mercenaries joined the British forces during the Revolutionary war that there was an increased use of decorated Christmas trees. The Hessians, from the German region of Hesse-Kassel, were reported to have set up Christmas trees in the homes of families where they stayed. They were also noted for their festive Christmas celebrations, which are reported to have led to their defeat by General George Washington at Trenton, NJ on December 26, 1776. Among the earliest documented use of decorated Christmas trees in North America are a decorated and illuminated Christmas tree that was set up in a German commander’s home to the north of Montreal, Canada in 1781 and a tree that was displayed at Fort Dearborn, MI in 1804.

So the finger points towards “the Germans” or more precisely the Germans in Strasbourg, a city which since 1681, under Louis XIV, has been ruled by France.

Ok, so the French have Strasbourg, but the Anglosphere caught the Christmas tree bug from the Germans in the era of Queen Victoria and Charles Dickens, right?

That is certainly the story I was familiar with. Specifically, in 1841, Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s beloved German husband, set up a fir tree at Windsor Castle for Christmas. And by the end of the 1840s, with an added push from the huge success of Charles Dickens’s Christmas Carol (1843), it had become an established tradition in England. From there it spread around the Empire and across the Atlantic.

Not so fast says historian Neil Armstrong! Writing in the journal German History he argues that we need to take a broader view than simply the Victoria&Albert connection.

This article examines the cultural transfer of Christmas customs from Germany to England in the long nineteenth century, and contextualizes the reception of new cultural practices by the English within the broader context of Anglo–German relations. Although the modern Christmas festival developed in parallel fashion in a number of countries, German customs, particularly the Christmas tree, played a significant role in the evolution of the festive season in England, and its configuration as a festival for children. The initial reception of Christmas tree rituals in England owed much to the activities of a small literary elite, who, particularly in literature for children, represented the Germans as an honest, simple and home-loving people, a theme which survived worsening Anglo–German relations in the late nineteenth century, and was a key narrative in the reporting of the famous Christmas truce during the First World War. It has also recently re-emerged in the popularity of German Christmas markets: they promote a vision of a timeless and authentic festival unspoiled by the taint of commercialism, which coexists alongside negative German stereotyping. The majority of nineteenth-century sources, however, failed to interrogate the German origins of the Christmas tree too closely, which encouraged the popular and enduring belief that Prince Albert introduced the Christmas tree to England. This reveals a strong tendency for imported customs to be naturalized and made palatable to the national story, and further complicates the process of trying to distinguish between cultural transfer and parallel developments.

And pause for a second, Christmas was German before there was a German nation state. Strasbourg, to which the tradition is ultimately traced, was under French rule from the late 17th century. The city was seized from France in 1871 as a result of the Franco-Prussian war, with many Alsatian residents loyal to France driven into exile (400k by 1910). Which means that whereas the British and Americans tend to credit “Germany” with the Christmas tree, French patriots in the late 19th century claimed the Christmas tree as a symbol of anti-German resistance.

See this illustration of the “Christmas Tree of the Alsatians and Lorrainers” even in Paris in the late 19th century.

As historian Susan Foley, explains, this Alsace and Lorraine Christmas tree event was: “Held annually in Paris from 1872 until 1918, the event aided children whose families had fled Alsace and Lorraine to retain French citizenship following France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. It also provided an afternoon’s entertainment for a paying audience. The Christmas tree was strongly associated with Alsace, and the event was a spectacle of patriotism, widely reported in the popular press. Through music, verse, and performance, those present mourned “the Lost Provinces” and celebrated the patrie, mobilizing for the Republic the emotions roused by the loss of Alsace and Lorraine.”

So everyone agrees the origin is Alsatian but they argue over whether that means that it is German or French. As for the innocence of German Christmas, take that with a big pinch of salt. Check out what is surely the spookiest carol broadcast ever: the Wehrmacht live broadcast of German soldiers singing “Heilige Nacht” from around the Nazi Empire in December 1942. TRIGGER WARNING!

So as a schematic one might think of different Christmases overlaying each other:

An “Franco-German-European Christmas”, freighted with cultural and historical weight. Let us call that the“politico-sentimental Christmas”.

And there is an “Anglo-American Christmas” fashioned by 19th-century bourgeois culture and 20th-century mass commercialism and mass production – “organized Fordist Christmas”, which now extends through its supply chains around the world

And, by the late 20th century, we have “global Christmas”. The majority of people celebrating Christmas today may not even be in the North Atlantic world, its original cradle. Christmas is now a global commercial event.

To give just three examples:

In Turkey since the early 2000s, Christmas trees and Santa were adopted as a New Year’s celebration.

Awareness of Christmas arrived amongst the elite in Japan in the Meiji period. But it became more popular in the 1950s. It no doubt helped that General MacArthur chose Christmas day 1949 to declare an amnesty for Japan’s defeated war leaders. In the context of postwar recovery and growth, Christmas in Japan became an aspirational family affair, closely associated with America and celebrated with a large white cake – yo-gashi – topped with strawberries. As one American cultural sociologist remarked rather sniffily in the 1960s: “The loan-word carol (karoru)” came to include “ecclesiastical songs as “White Christmas,” “Jingle Bells,” and “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”“

And in China, Christmas has become an event for fashionable youth to camp out in the Malls and enjoy the decorations.

Indeed ahead of 2020, so enthusiastic were Chinese celebrations of Christmas becoming, that in 2018 the authorities tried to crack down and to demand priority for traditional Chinese festivals. And some brave Chinese shoppers are back in the malls today!

Whether the Chinese regime’s crackdown will work or not, as cultural anthropologist Daniel Miller argues:

…. Christmas has become central to three of the most important struggles that define being modern. The first is our relationship to family and kinship, the topic that was always at the heart of anthropology. A second is the problem of how we reconcile our desire to be citizens of the globe in its entirety without losing our sense of the specifics of local origins, or relation to the places we come from. And the third is our problematic relationship to mass consumption and materialism. I shall end with an attempt to construct a general theory of Christmas that combines these ethnographic observations of contemporary Christmas with the earlier historical materials.

Don’t worry, I am not going to try to lay out a general theory of Christmas here. But, wherever you are and however you celebrate, indeed, whether you celebrate or not, Chartbook Newsletter wishes you a very merry time.

h/t Becky Conekin.