The ski business worldwide.

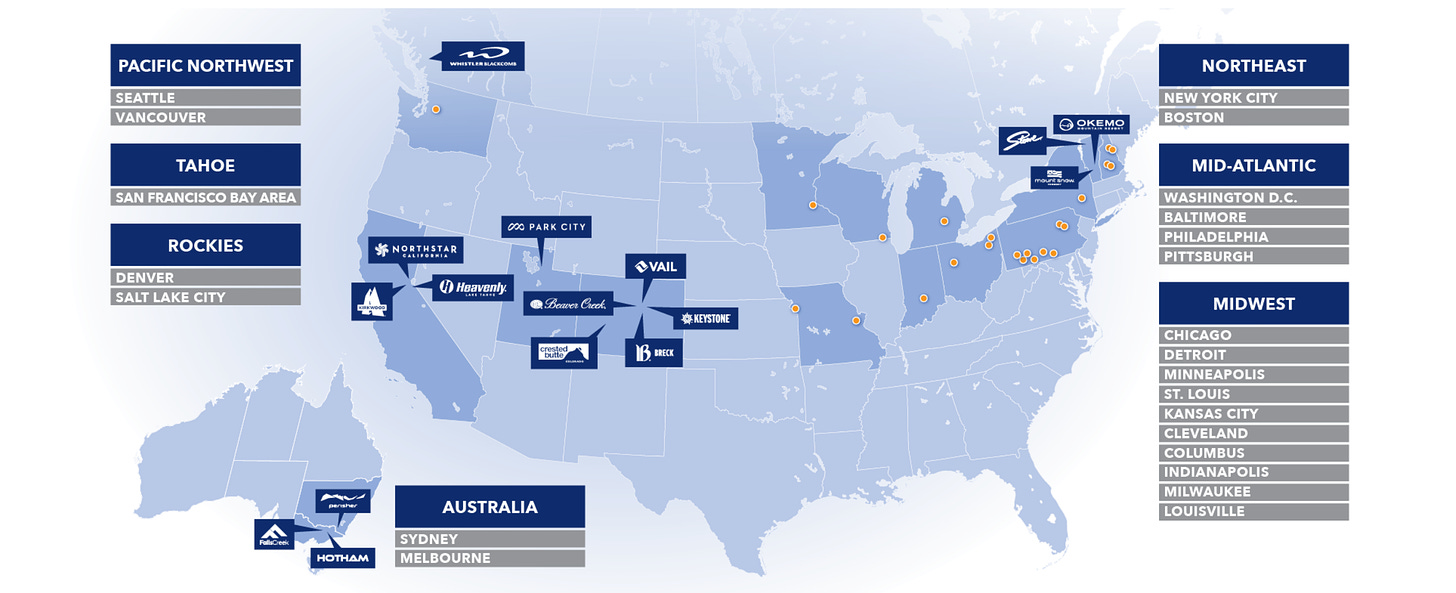

Source: Vail

Do you ski? As a matter of lifestyle and recreational distinction, it is a question up there with “do you play golf?” or “do you play chess?”.

Of course, if you are born in cold regions of the world, or in the mountains, the answer, regardless of social class and cultural milieu, is likely, “yes, of course, I ski”. For everyone else, it’s a telling question indeed.

For those mulling the seasonal question, Ones and Tooze is to hand this week to help you sift through the noise, with an episode on the war in Ukraine and the economics of snow.

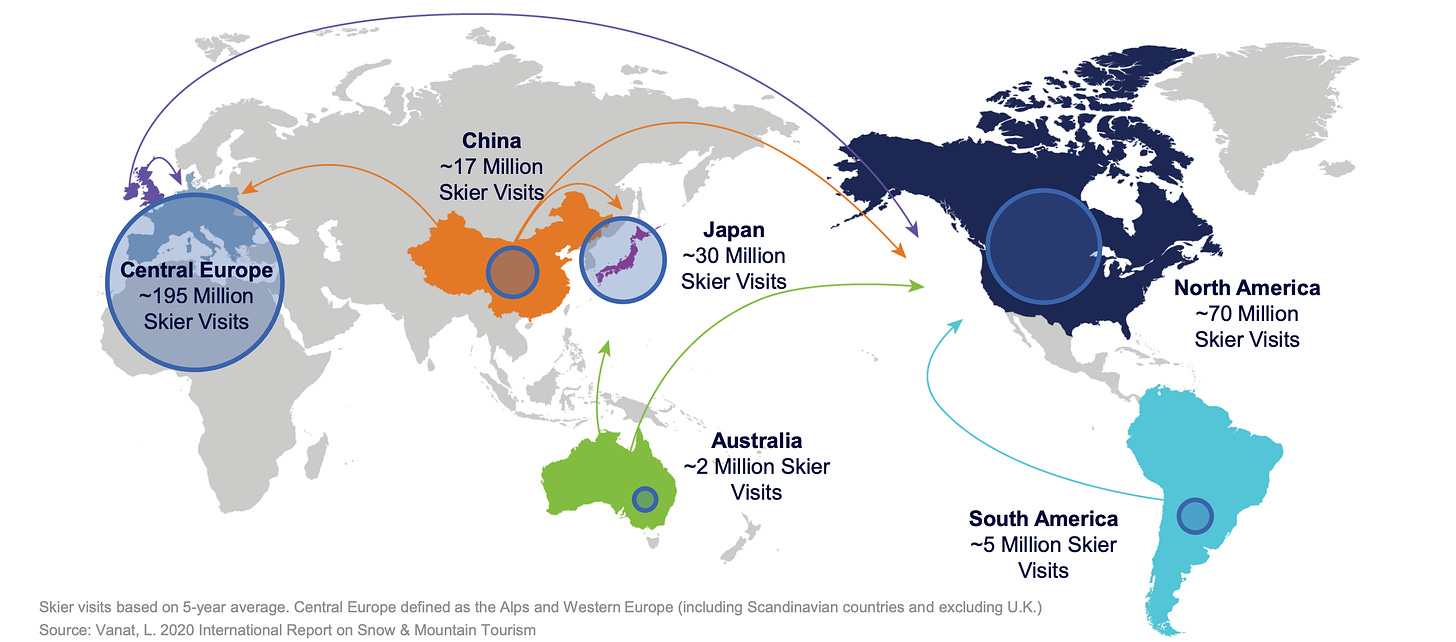

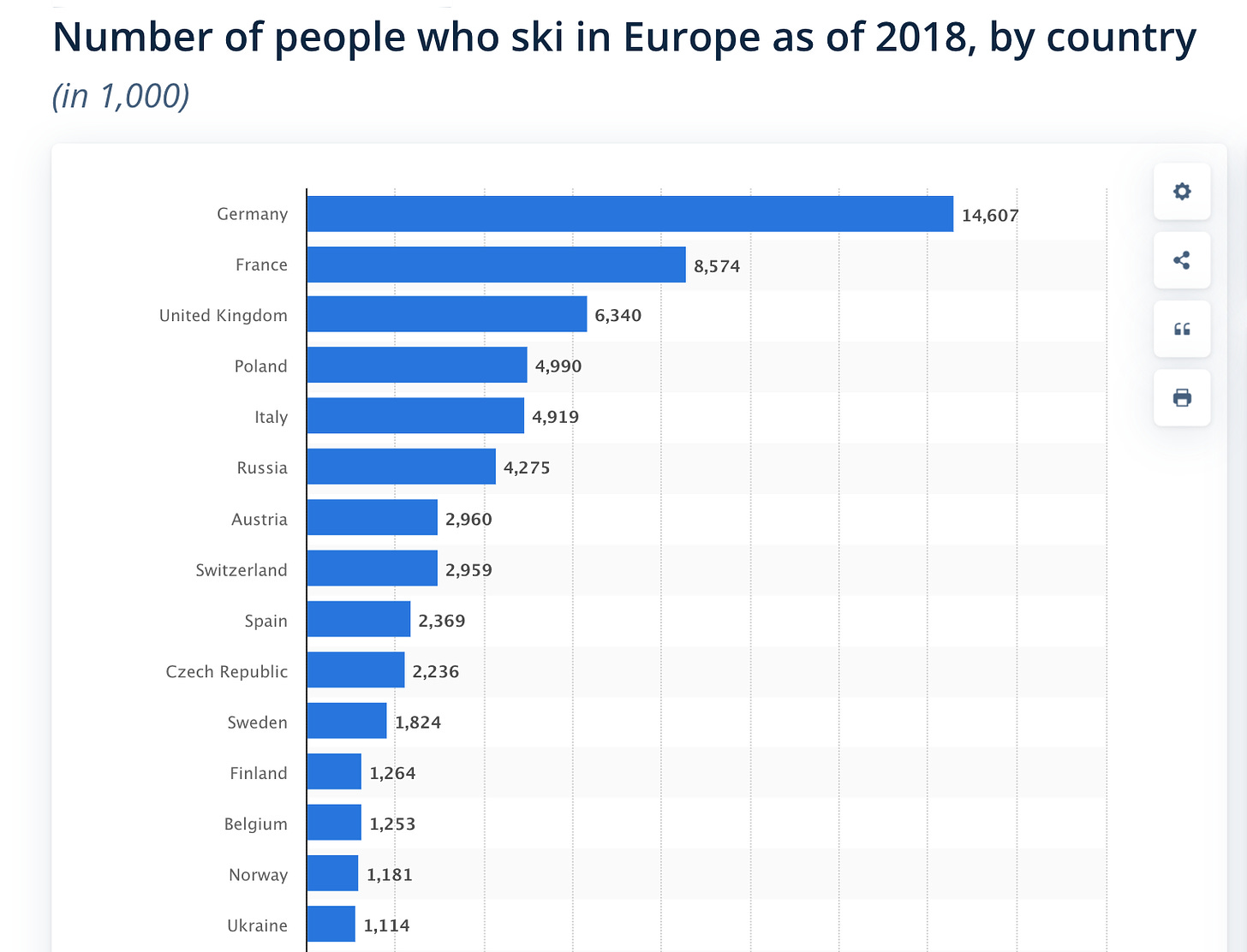

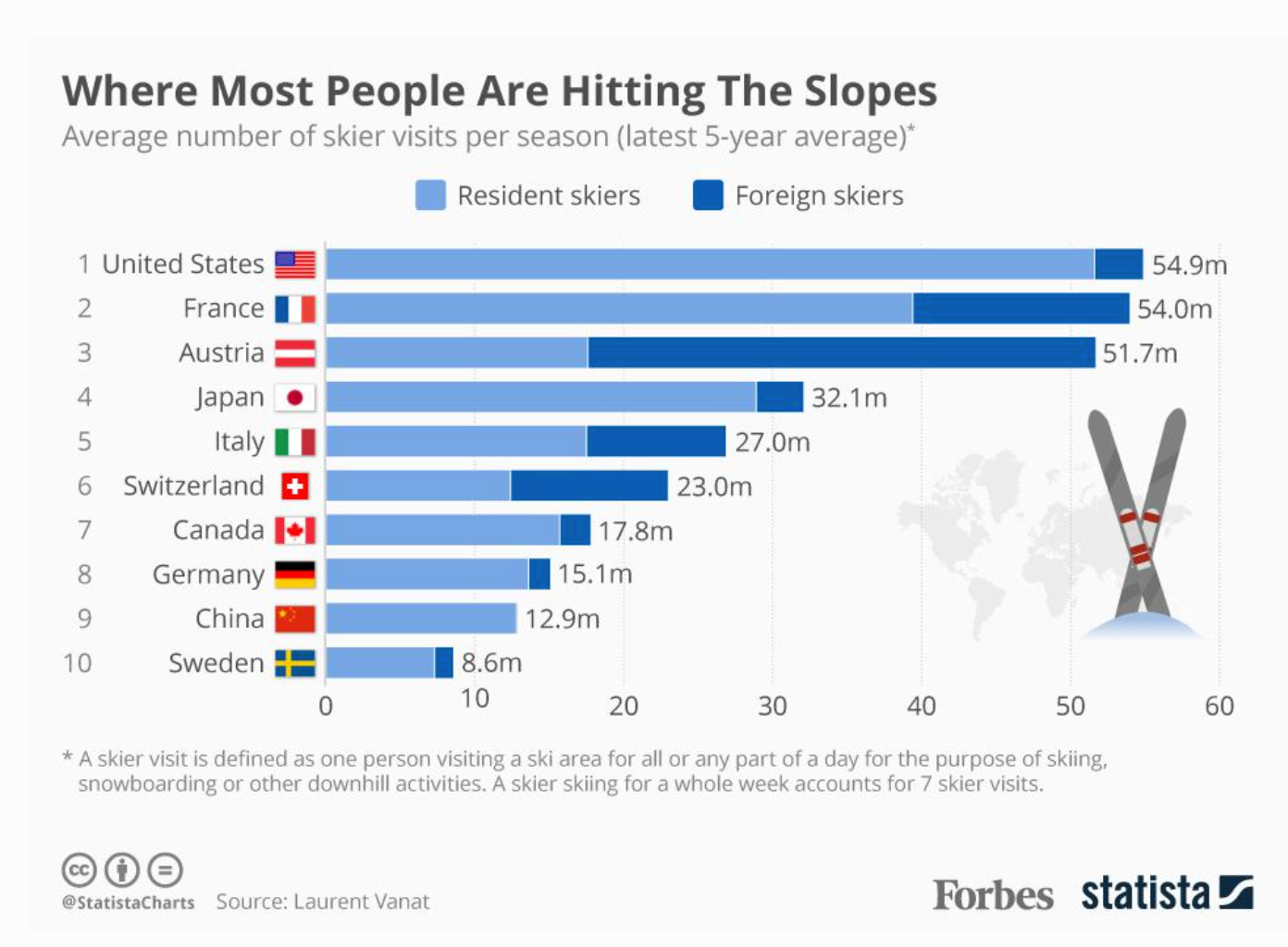

Of 8 billion total population worldwide, it is thought that about 135 million people regularly ski, so about 1.5 percent. There are c. 2000 alpine skiing destinations in the world with the vast majority in North America, Asia and above all Europe. Unsurprisingly, given that the cost of even a short skiing trip can easily run into many thousands of dollars per person – allowing for travel, lodgings, ski pass and equipment – skiers are an affluent group. Roughly 20 million of the world’s skiers in any one year are in the US, if you include snowboarders. 15 million or so come from Germany.

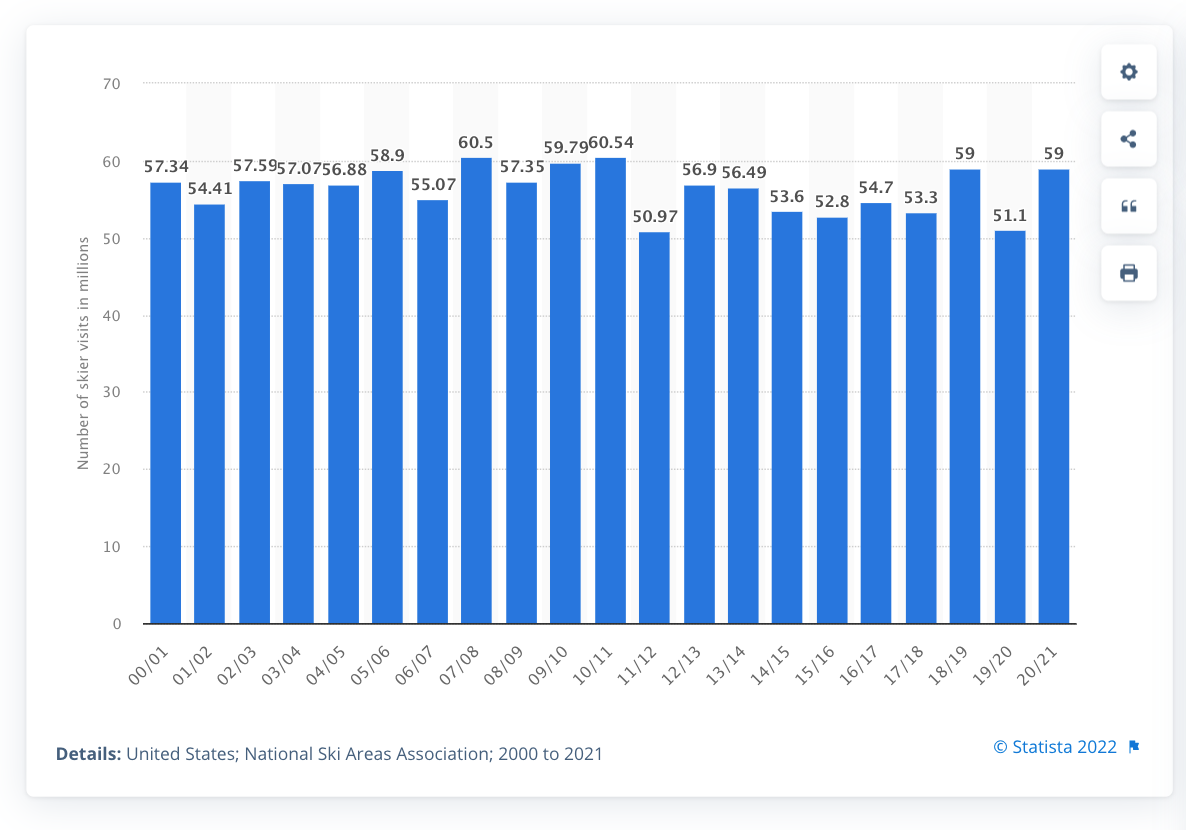

Despite economic growth, the number of skiers worldwide is increasing very slowly. Globally, the annual number of skier-days has plateaued at around 400 million. The Alps account for 43 percent of all skier days globally and Europe is by far the largest alpine market, with typically around 210 million skier days a year. In the US, the number of skier-days has been static between 50 and 59 million per annum for the last 20 years.

Source: Statista

In a world in which both population and incomes generally trend up, a static number implies that participation in skiing is trending down. In some markets, notably in Europe, the downward trend in participation is very pronounced indeed. Skiing is, in short, becoming more, not less exclusive.

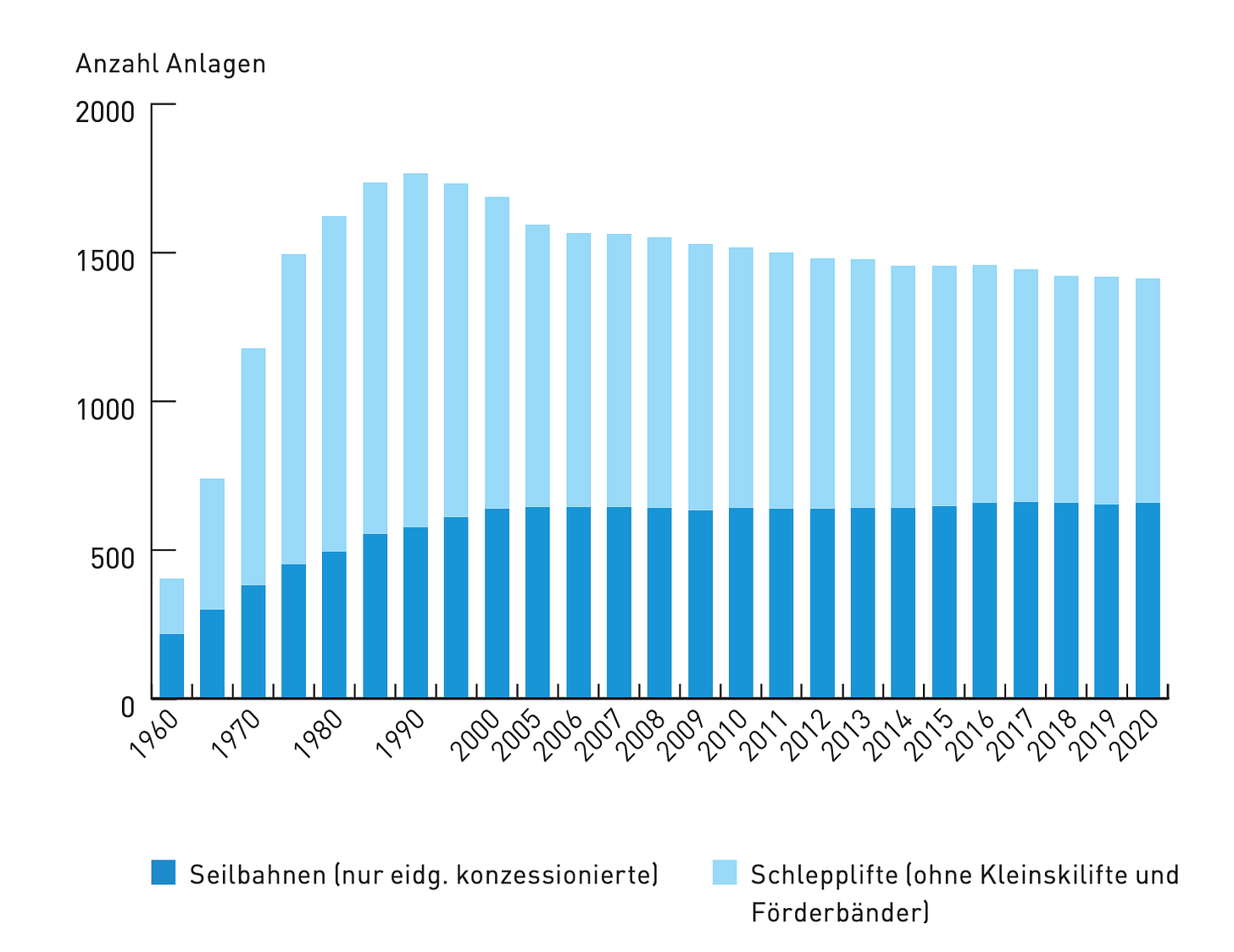

This is an effect of changing habits. Skiing is seen as a bit of a period piece, a sport that “was once” chic. Nor is this merely a matter of fashion perception. It reflects the actual history of the industry. Take, the history of the ski lift system in Switzerland.

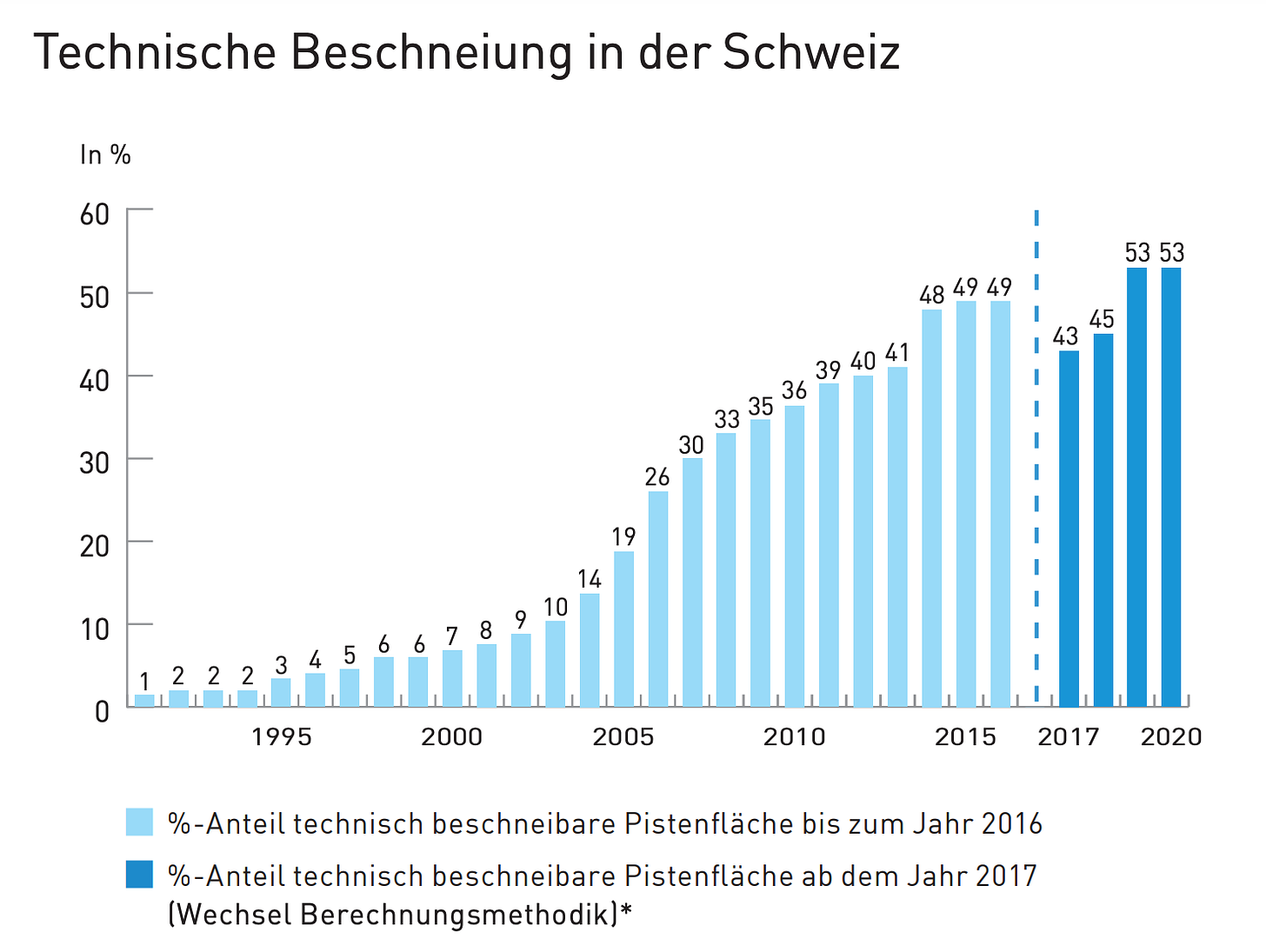

Source: Fakten und Zahlen zur Schweizer Seilbahnbranche

The period of growth in the Swiss ski resort industry was between the 1960s and the 1990s when capacity increased fourfold. Since then it has been static. Old systems are being improved and maintained, but no new lifts are being built. In the US there is more expansion. But the point stands. The boom in skiing happened thirty to fifty years ago. It shaped two generations of enthusiasts, who presumably pass on their passion to their children, but is not driving dynamic growth in the 21st century.

This keys with my own biography. Having recently moved to Germany, in the early 1970s my parents took us on one fraught outing to the slopes, where, even as a child, I remember a lot of anxious talk about money and where I discovered a painful and embarrassing skin rash brought on by exposure to high levels of UV light.

You might wager that the current plateau in the skiing business had something to do with climate change. A warmer world means that there is less snow to go around. More on that below. But, beyond lifestyle currents and the natural environment, the factor we should not ignore is political economy and corporate strategy. A market will remain static if there is no reason to invest in expansion, if the status quo is profitable for the major players.

The political economy of winter sports is not a large field. But in researching Ones and Tooze this week, I stumbled across a rather brilliant piece of work by a student at UT Austin, Adam L. Roossien, whose 2017 undergraduate thesis, “Industry v. Lifestyle: A sociological study of downhill snow skiing in North America” opened my eyes to a facet of global capitalism I had never considered before. Thank you Mr Roossien! Thank you to google scholar for serving up such excellent stuff!

You might think of the ski industry as epitomized by rustic Swiss chalets, cute mountain villages, glamorous “ski instructors”, a staple of 1970s erotic fantasy, tingling apres-ski and sun-burned young folk in the surfer/skateboarder/snowboarder vein. Roossien’s essential insight is that the industry is far better understood as an example of capitalist monopolization. As he points out, between 2000 and 2017 “the price of downhill snow skiing has risen nearly 200%. Over the last five years, this price escalation has picked up, and the price of downhill snow skiing has risen 75%.” To paraphrase Warren Buffet, the business logic is not so much one of building moats, but of buying mountains.

Mountain slopes are a limited resource. In Europe great resorts like Val d’Isère began to be developed in the interwar period. In the thinly populated mid-West of the United States, the slopes were prospected a generation later. This, for instance, is how the story of the Vail resort is told:

Vail Resorts was founded as Vail Associates Ltd. by Pete Seibert and Earl Eaton in the early 1960s. Eaton, a lifelong resident, led Siebert (a former WWII 10th Mountain Division ski trooper) to the area in March 1957. They both became ski patrol guides at Aspen, Colorado, when they shared their dream of finding the “next great ski mountain.” Siebert set off to secure financing and Eaton engineered the early lifts. Their Vail ski resort opened in 1962.[2]

Today, ski resorts are in regions tightly protected by national parks and nature reserves. You cannot build new resorts. Corporate interests have taken advantage of this tight regulation to establish dominant positions in the two largest Alpine ski areas in the world – the US and the French Alps.

Roossien’s muckraking thesis is an American one, but the strategy appears to begin in France with the Compagnie des Alpes, founded in 1989 and establishing a dominant position in the best-known French resorts – including Tignes, Val d’Isèere and Chamonix.

In the US it is Vail that has expanded since 1996 to establish an overwhelmingly dominant position. Along with slopes of Vail itself, the Vail Corporation also owns Beaver Creek, Breck, Park City and Whistler. Depending on the measure used, Vail controls 40-50 percent of the skiing market in the United States.

Vail’s vision is to own as many of the best mountains, slopes and resorts as possible, raise these to a high level of high-priced service by investment and then to feed demand for high-profile glamorous destinations from more local and regional resorts. To warrant billions of dollars of investment in a high-end and exclusive leisure segment, the corporate strategy is to turn unpredictable revenue from ski lift passes, purchased as and when, into a business-model based on advanced commitments. To do so, in 2008 Vail introduced the EPIC ski pass that gives access to large part of its network. In exchange skiers make an advanced and non-refundable commitment to the purchase of a pass that now costs in the region of $1000 per season.

The risk of bad weather or changed holiday plans is thus transferred from the company to the purchaser of the pass. As Vail describes it in a 2022 investor presentation.

“Our North American season pass program has grown dramatically over the past three years as we have focused on our core strategy of shifting guests from lift tickets into advance commitment to drive stability and long-term value for the business. … We expect to have approximately 2.3 million guests in advance commitment products this year, generating over $800 million of revenue and representing over 70% of all skier visits committed to our 40 North American and Australian resorts in advance of the season in a non-refundable pass, an increase of over 1.1 million guests in the program from the 2019/2020 season, including all pass products for our North American and Australian resorts.

More broadly Vail has re-envisioned the resort business as a data-driven subscription-based business model where the aim is to know as much as possible about the high-income, high-net worth segment and tie them into regularly annual down-payments on ski passes. Currently, Vail boasts of having data on over 22 million skiers in the US and estimates that it covers 53 percent of all North American destination guests.

The result is to turn skiing into an increasingly corporate, exclusive pursuit. This may be profitable, but Roossien’s thesis is that it is ultimately a model that is destined to self-destruct.

… Vail’s corporatization (of skiing) is leading to the severe marginalization and destruction of snow skiing subculture. Due to downhill snow skiing’s foundational dependence on its rich and distinct subculture, this cultural destruction is causing a deterioration of the sport itself.

Interestingly, Vail seems to be well-aware of the narrow socio-cultural base of its market segment in the United States. This is why it aims for long-run global expansion. It is targeting Europe, where it is attracted by the “broader demographic appeal of skiing relative to North America”, and Asia, where it sees huge growth potential beyond the bounds of North American ski culture. In Vails’ corporate vision, expanded and upgraded Japanese ski slopes will meet mounting demand from both Australia and China.

In 2022, hanging over any discussion of snow is the question of global warming. Even under more normal conditions, weather was always a risk factor for the ski business. The only guarantee of snow is altitude and correct positioning on mountain slopes to catch precipitation, but higher altitudes makes resorts less accessible and more expensive to maintain. Climate change makes these risks even more serious. The European Environment Agency reports that the length of snow seasons in the northern hemisphere has decreased by five days each decade since the 1970s and the Alps are warming faster than practically anywhere else on earth.

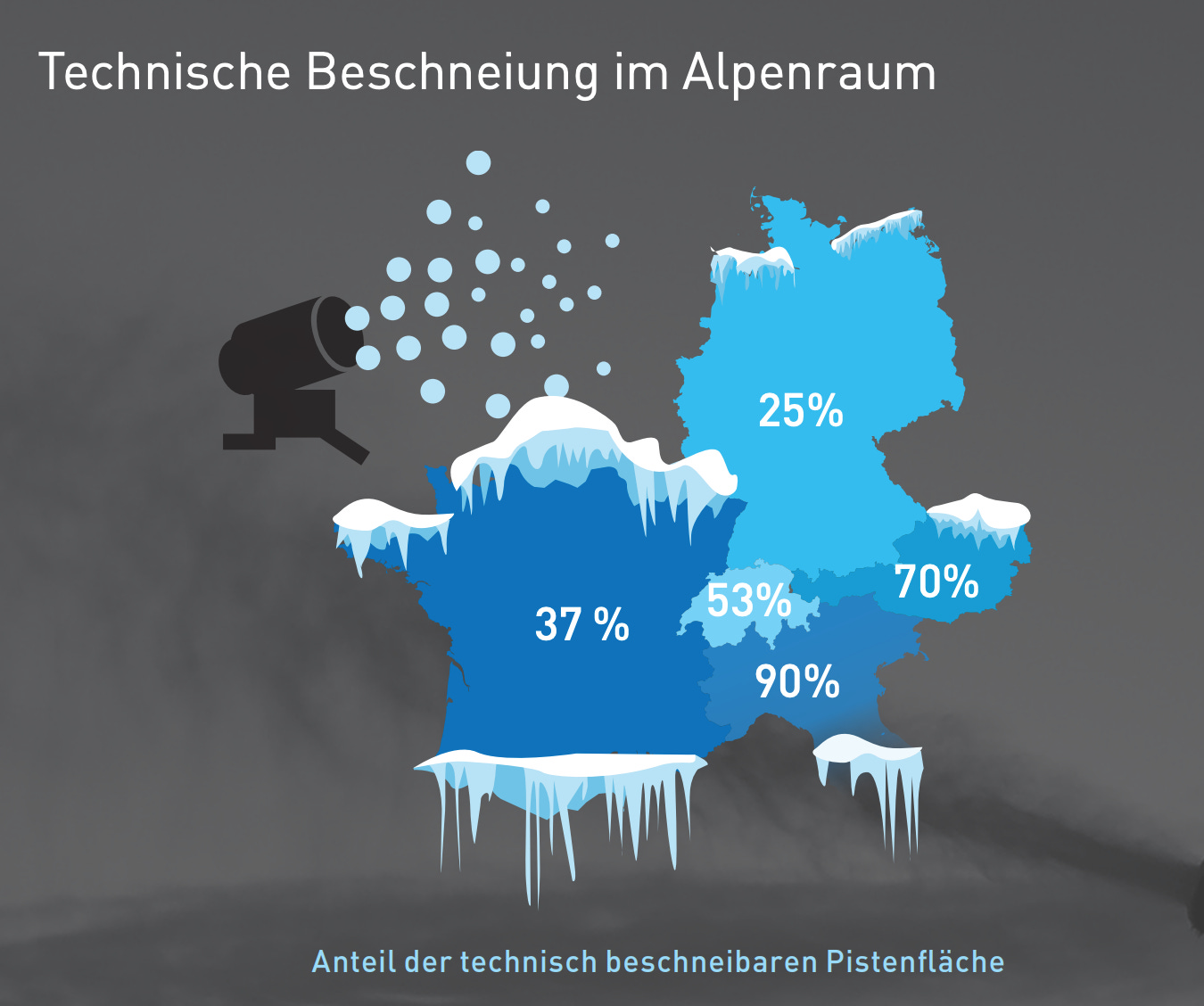

The answer, increasingly, is the large-scale deployment of snowmaking machinery that allows slopes to be brought into use and kept going more reliably. In addition resorts engage in “snow farming”, to build up drifts, and “snow grooming” to maintain attractive conditions for skiing.

The first snow cannon was invented in the early 1950s and resorts in the Catskills became the first in the world regularly to use artificial snow. By the 1970s snow cannon were in widespread use in Europe as well and since the early 2000s there has been a huge surge. Here are the numbers for the share of Swiss slopes that can be provided with “technical snow”.

Currently, Switzerland has a stable share of 50 percent of its slopes that are worth maintaining with artificial snow. That places it between the German and French slopes, which tend to rely on natural snowfall and the Italian Alps where snowmaking equipment was introduced in the 1980s and 90 percent of the slopes are today maintained with artificial snow.

Since 2000 none of the winter Olympics would have been possible without artificial snow and snow farming.

FYI: Snow canons are artificial devices and they are bad news for the environment, but they are not quite the nightmare one imagines. Crucially, they do not involve, as you might fear, gigantic amounts of outdoor ice-making, as in the horror vision of “ski slopes in the desert”. Standard snow canons, are operated in low temperature environments where water freezes naturally. By pumping water and dispersing it as a spray, they increase the cooling effect through evaporation, and create a mist that freezes into artificial snow crystals. The electric power demands are modest, essentially for pumping and dispersing the water spray and if the electric power is supplied from renewable sources e.g. alpine solar, then the main concern is the gigantic consumption of water. What you are replacing with artificial snow is less the low temperatures than the lack of precipitation at key moments in the year. Nevertheless, in the Alps in particular, the future of skiing is the future of a giant environmental engineering project.

That innocent seasonal question, “do you ski?”, does indeed carry a lot of weight.

****

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. I love sending out the newsletter for free to readers around the world. I’m glad you follow it. It is rewarding to write, but it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, there are three subscription models:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

Several times per week, paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images. To get the full Top Links and become a supporter of Chartbook, click here