Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is driving Europe to reconsider its energy policy options.

I featured the German debate about immediate sanctions in Chartbook #97.

Chartbook on Substack

Since then, the substance of the German debate, or rather the lack of substance in the debate, has been disappointing.

I want, instead, to focus on three excellent contributions that are all pitched at the broader European level.

Following the invasion, on 11 March 2022, EU heads of state agreed to phase out EU dependency on Russian fossil fuel imports as soon as possible. With this target in view, the European Commission will prepare a “RePowerEU” plan to be presented by the end of May 2022.

The most substantial is the memo from Agora Energiewende written by a team headed by Matthias Buck. They makes a powerful case that the principal goal of energy policy in Europe at this moment, should be a step change in efforts to reduce fossil fuel consumption. This will be done by an urgent new drive to increase efficiency of energy usage and a major new wave of investments in renewables.

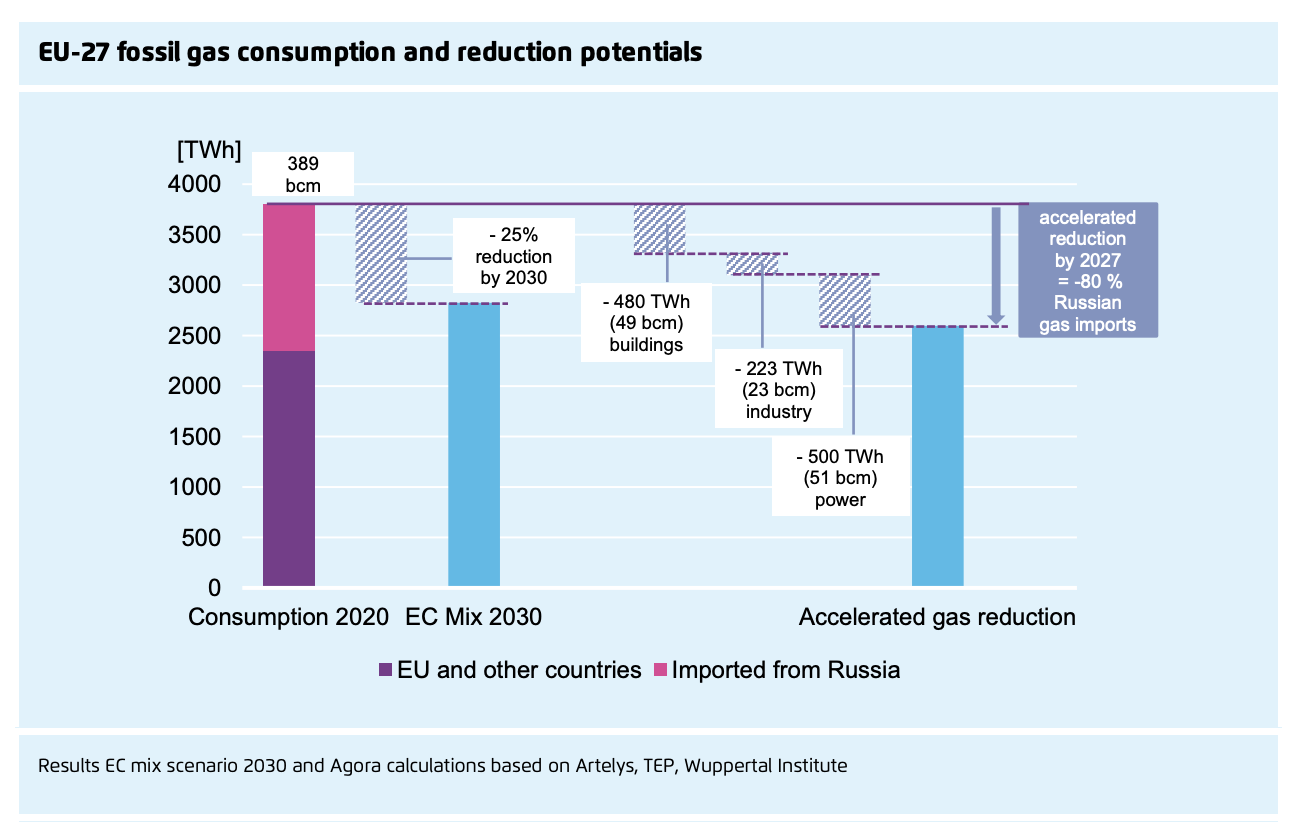

As the Agora Energiewende team argue. By 2027, energy efficiency measures, district heating and a massive, continent-wide drive to install heat pumps could save 480 TWh in energy used in buildings. In European industry, likewise, efficiency measures and electrification in low and medium temperature heat processes can provide for 223 TWh savings. In addition, a dramatic ramp up of wind & solar PV installation combined with more system flexibility could contribute 500 TWh in the power sector.

Together these measures would take out 80% of the energy demand currently covered by Russian supplies.

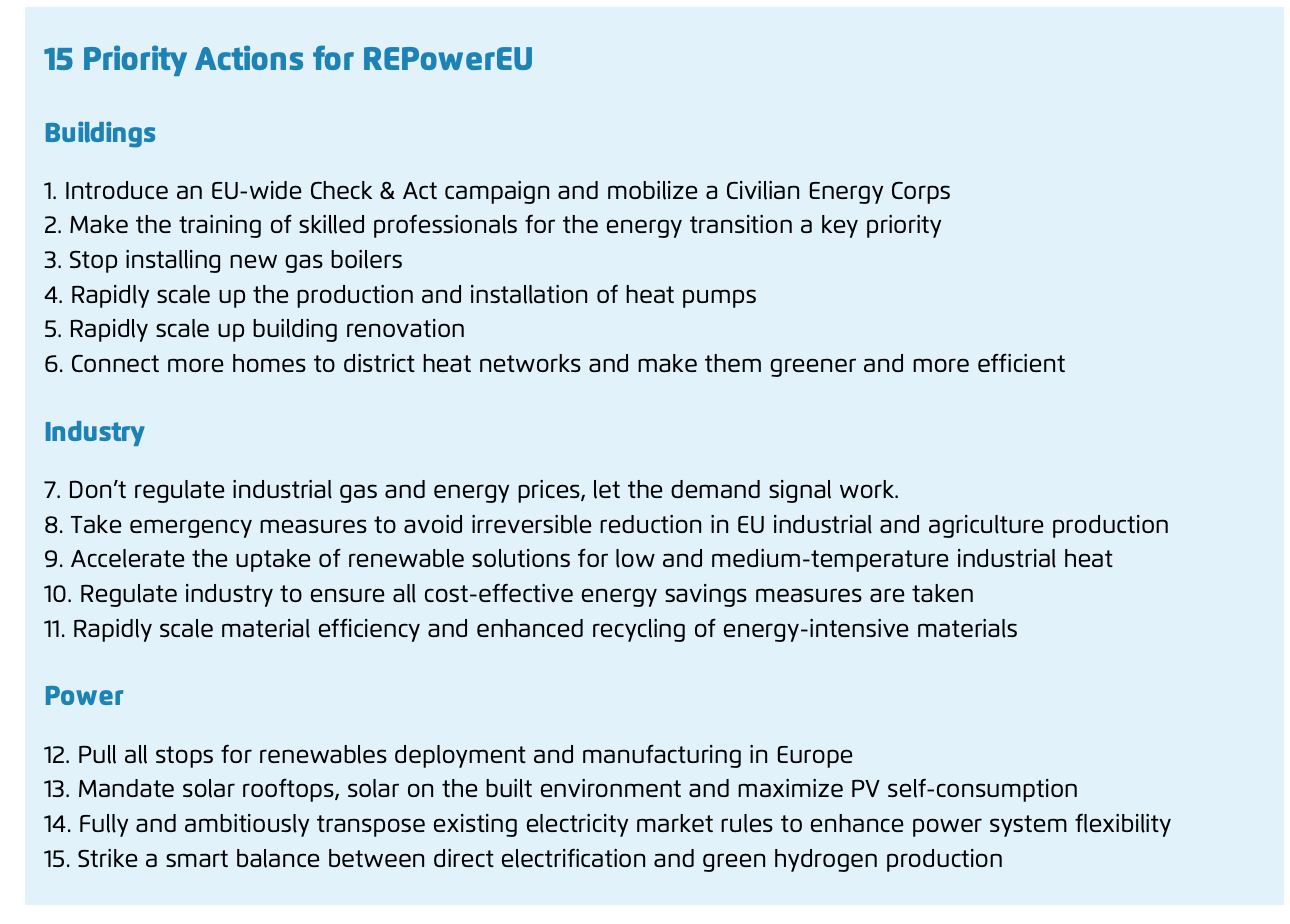

The specific list of 15 proposals is no ambitious, but also seems doable.

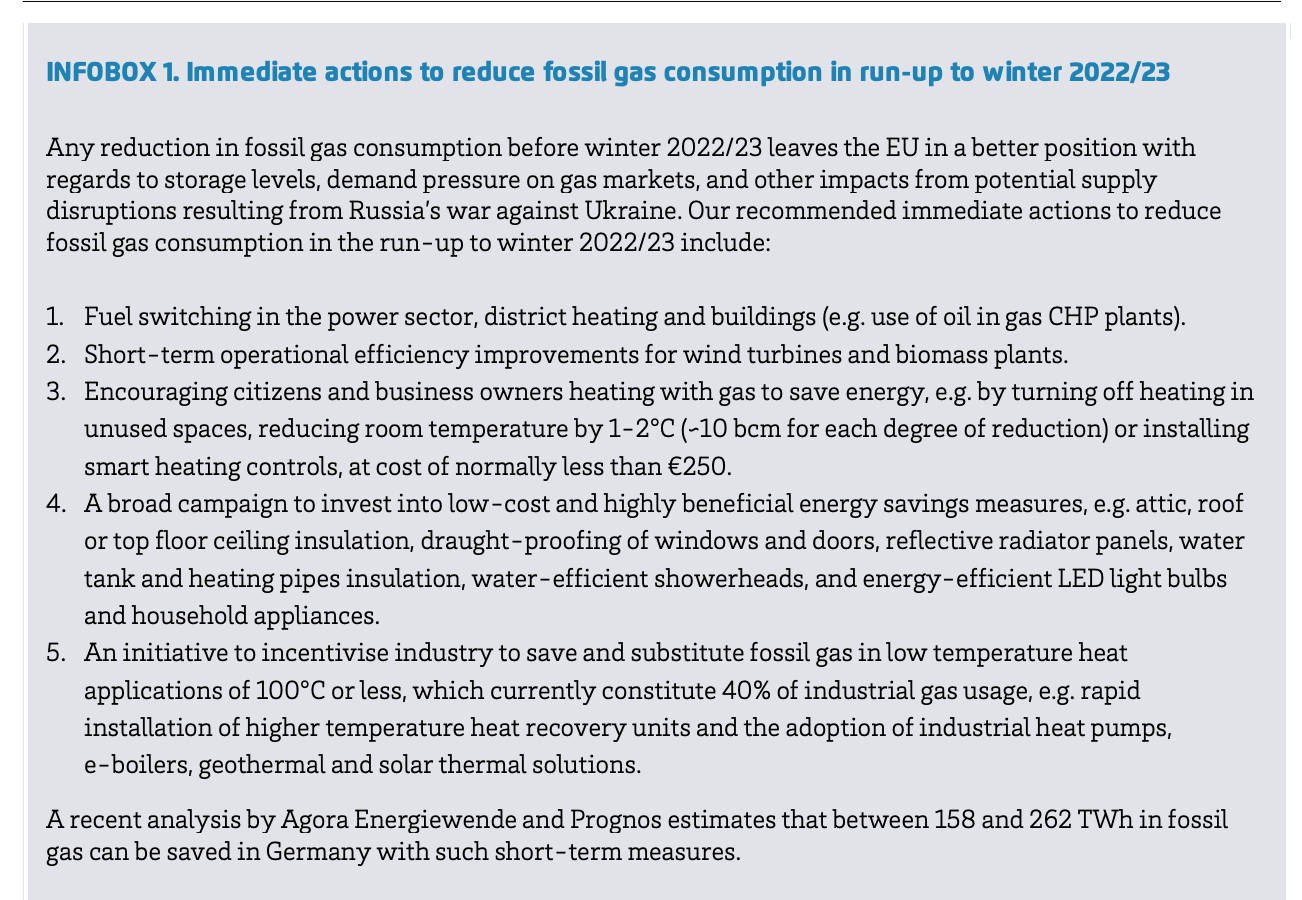

One particularly interesting aspect of the report is the attention paid by the Agora team to what is the most urgent issue in political terms: the crunch that Europe and Germany in particular is likely to face over the winter of 2022-23.

Getting broad-based buy-in for some packages of measures of this kind in Germany, is crucial if Europe is to harden its position versus Putin on energy imports.

One of the things that makes these kind of proposals so dizzying is the way that they spell out the relationship between macro-level concerns of geoeconomics, and the minutiae of heat pump installation and the efficiency of boiler operation. This gives a whole new meaning to the notion of realism in that it forces us to reckon with the fact that very large-scale trade offs depend on rather small-scale technical knowledge. And we need that knowledge not just to assess the hypothetical viability of a program. We need it to be embodied in the labour force, if any of this is going to happen.

Finding these efficiency gains and then training the skilled labour to actually carry out the program will require huge parts of European society to become much more savvy and expert in all things energy. It is akin to the revolutions implied by motorization or digitization. We need the entire chain of energy production, distribution and use to be brought out of the black box and opened up to massive collective experimentation and implementation.

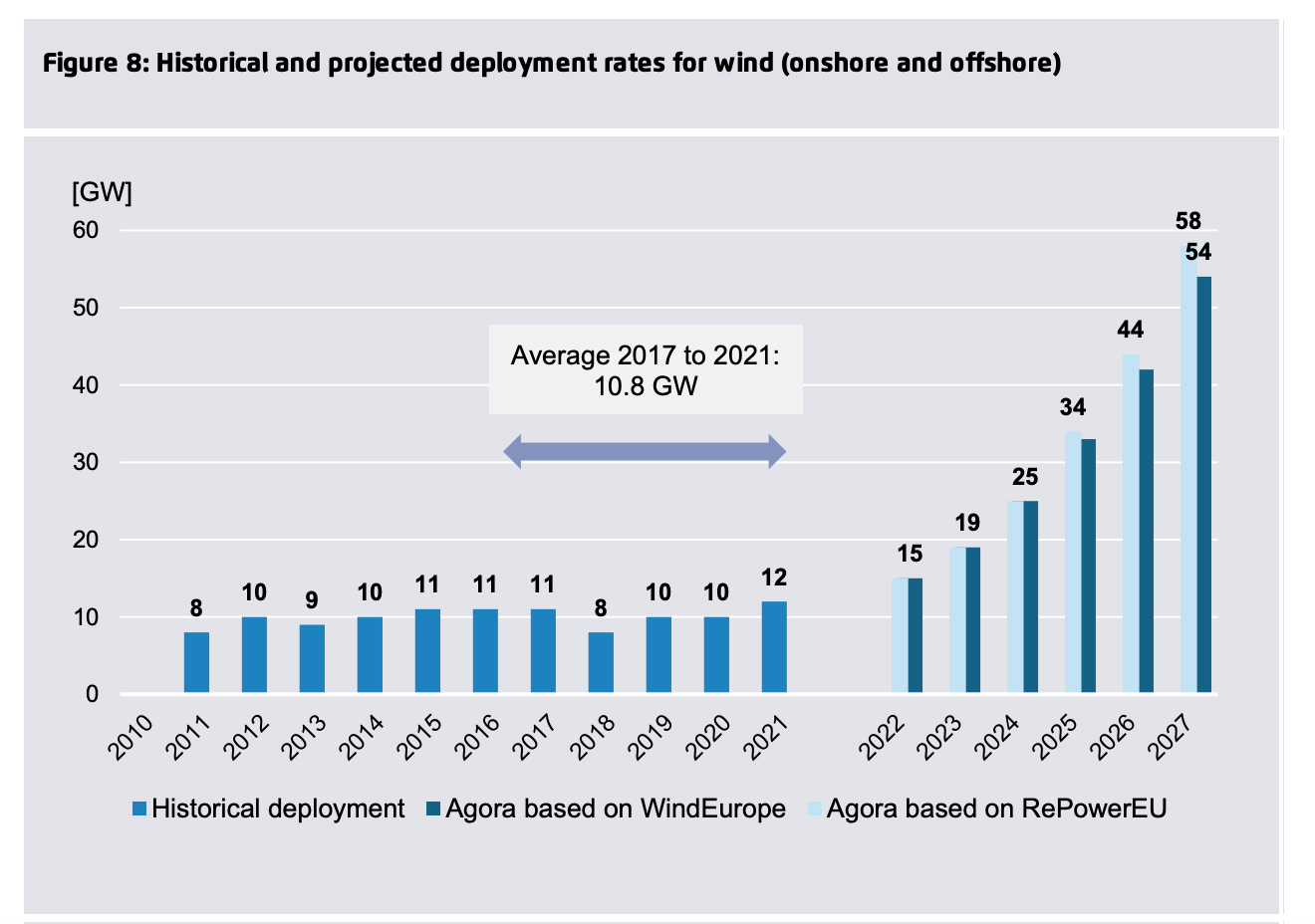

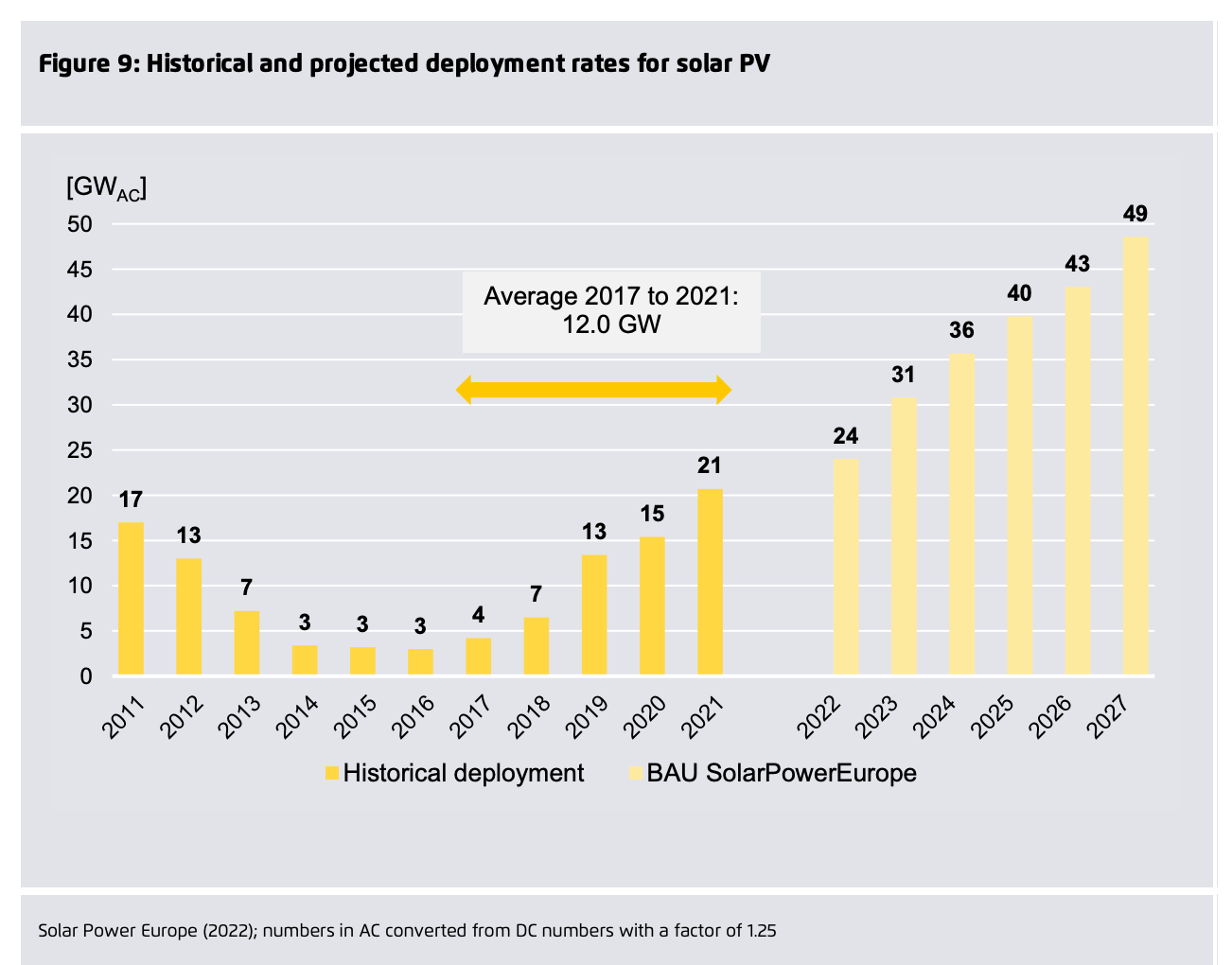

To achieve the targets now set for Europe’s renewable energy capacity by 2030 – to get from 350 to 900 GW within 8 years – will require, as the Agora team point out a “true European industry project”. The rate of annual new installation needs to surge at a spectacular rate.

Are these rates of installation plausible? Are they realistic? As Agora comments:

The updated wind power installation target of 480 GW by 2030 is aligned with the industry’s estimates for the end of the decade, provided an enabling regulatory framework and favourable funding conditions are in place. Around 80% of the new wind turbines will be built onshore, the rest offshore. However, an instant and real gearshift in scaling new wind turbines is needed to reach the projected deployment pathway. While the RePowerEU target for wind reflects the upper end of industry’s potential, the solar PV industry could see Europe reach an installed solar capacity of around 600 GW by 2027 under its “accelerated high scenario” – assuming that the EU were to follow an ambitious high policy support regime mirroring China’s approach to solar PV expansion.

If you look at the recent trajectory of solar installation in the EU it becomes clear that what is needed is a dramatic turnaround. Since the highpoint of 2011 it has been heading in the wrong direction.

In the long-run using less energy saves money. The Agora team estimate that currting 1200 TWh reduction in gas consumption by 2027 would save an estimated 127– 318 billion euros and generate additional savings going forward. The savings would be even larger if prices were to settle at the hugely elevated levels we have seen recently.

But, getting those savings will require investment.

The Agora team suggest that their measures would need to be flanked by a new EU Energy Sovereignty Fund, modelled on NextGenEU and equipped with 100 bn EUR until 2027.

This figure is not the cost of investment, which will be far higher. It is the public support necessary to make renewable projects investible and to stabilise their revenue streams. How much subsidy is actually needed will vary depending on how expensive fossil fuels become (the more expensive the better from this point of view) and Agora suggests a bandwith from 30 billion to 285 billion euros, in the event that fossil fuel prices were to plunge.

As an important side note, the Agora team note that

Transmission and distribution grid investments were not modelled as part of this analysis. Based on various scenarios (Goldman Sachs, McKinsey, Eurelectric and EC modelling), estimates range from 0.9 billion euros to 3 billion euros of grid investments per additional GW of RES in the EU, resulting in 470–1650 billion euros of cumulative grid investments for this decade. This compares to 130 bn between 2011-2020 according to Commission data.

Given all the various measures needed to address the crisis, these estimates seem on the modest side. Mario Draghi has spoken of 2 trillion euros in spending on energy, defense and social welfare to cushion the impact of the shock. That raises the issue of Europe’s fiscal constitution.

In 2020 Europe made a huge leap forward with the issuance of common debt to finance the NextGen EU program. Christian Odendahl and John Springford of CER argue that the same approach should be taken to finance the response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

The necessary spending should be financed by raising taxation, cuts to fossil fuel subsidies, national borrowing and a new program of common borrowing.

During the pandemic, Europe has found common resolve in fiscal policy few thought it could gather. Considering that Europe’s security (and once more its economic recovery) is at stake, it is also in the interests of the richer North that the East and the South are able to invest. The Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is a smart combination of transfers from richer to poorer member-states, and cheap loans (in effect, subsidised national borrowing), in return for reforms and investment commitments. Europe should put together a RRF 2.0 to focus on energy that is green and secure, that is, on projects that can rapidly reduce the need for imported fossil fuels. That would make Europe as a whole less vulnerable to Russia, and will allow all countries to invest in energy and defence with the same boldness that Germany has done.

European policy-makers should use this crisis to secure the triple dividend that green investment can bring: make Europe less dependent on Russian energy, help fight inflation and reduce Europe’s carbon emissions. Match that with a triple funding of taxation, national and European borrowing, and Europe will have made another big step forward towards meaningful integration where it matters: in protecting two of Europe’s most important public goods, security and a stable climate.

The argument over the future of the EU’s fiscal constitution had begun already before Putin unleashed his war. It is now more urgent than ever.

In 2020 the EU demonstrated the creative effect that can be achieved not by rehashing old points of contention, but by setting a new agenda. In that spirit Martin Sandbu makes a typically constructive suggestion in his regular column in the FT.

If the EU is going to go through a painful phase of transition in weaning itself off Russian gas, why not turn this into a driver of a new common policy of energy purchasing.

Europe can also turn energy policy into an active tool of external influence. The EU is — not before time — probing its ability to constitute a buyers’ cartel. … on Friday the European Council vowed to work on a common purchase platform. This is a momentous move. Consider the global effects should EU countries collectively procure and manage the gas needed to fully replenish the bloc’s gas storage every year. That would mean annually buying up to 100bn cubic metres of gas, about one-tenth of the world’s annual trade. If it was all bought as liquefied natural gas it would be one-fifth of the LNG market. If largely concentrated in the summer, the temporary market share would be higher still.

In the short-run this will likely drive prices up, but, as Sandbu points out, from the point of view of the energy transition that is only to be welcomed.

In the long run, joint procurement would make it easier for EU countries to pre-announce plans for scaling down gas use — which, through its global market influence, would cast doubt on the wisdom of investing in long-term gas development elsewhere. The overall effect would be a boost to incentives for global renewable energy investments today.

The EU is not ready overnight to become a gas-buying cartel at scale. It will have to build up expertise and boost its regasification and domestic piping capacity. … The 1970s shocks came from the young Opec flexing its muscles. The 2020s shocks should give birth to a European anti-Opec.

Again and again, the arguments comes back to this double point – expertise and investment. Plus, the political coalition building implied by Odendahl and Springford’s financing roadmap.

Upcoming on Chartbook:

The 2nd round of the exchange with Unhedged – on Larry Fink and the end of globalization.

More on Mariupol

Barry Eichengreen’s vision of the dollar’s future as a reserve currency

In medias res: An appreciation of Deborah Cohen’s brilliant Last Call at the Hotel Imperial

Luxembourg: the making of a European financial center

and I guess I probably will have to say something about my vision of “synthesis”.

Thanks to everyone for their support and a many kind words of late. It means a lot!