On March 8 as the global market for Nickel seized up and commodity markets spasmed, the European Federation of Energy Traders, a leading industry group, called on central banks to provide liquidity to support vital commodity markets.

The 4-page letter from lobby group the European Federation of Energy Traders pleading emergency liquidity support in full (with my own highlights).

— Javier Blas (@JavierBlas) March 16, 2022

EFET represents top trading houses, oil companies and utilities (think the likes of Vitol, BP, Trafigura, Uniper, Engie…) #OOTT pic.twitter.com/cVxzlqrJrO

Clearly the Ukraine crisis is a political and geopolitical event of the first order but in recent weeks many of us have been asking, how it might impact the global financial system. Does the letter by the commodity traders sound an important alarm?

At first it seems counterintuitive to imagine that markets with surging prices could be a source of financial distress. The more obvious line to pursue is the one suggested by a quip in the FT’s lex column.

Financial warfare creates collateral damage — and damage to collateral.

Robert Armstrong, for instance, in the excellent Unhedged newsletter explored the potential impact of sanctions on the finances of Russian oligarchs.

Following Zoltan Pozsar’s lead I did Chartbook #89 on Russia sanctions and the global dollar system.

Chartbook

Chartbook #89 Russia’s financial meltdown and the global dollar system. The Western sanctions on the Russian financial system announced over the weekend are doing their work on Monday. As far as Russia is concerned, financial markets are around the world have become a legal battlefield…

It is also clearly the case that the Ukraine crisis sharpens the dilemmas facing central banks around the world. Balancing inflation risk has become far more difficult. More on this in a future Chartbook.

But what has become clear in recent weeks is that key market-makers in commodity markets are struggling to cope financially with the huge surge in prices and the ensuing volatility.

Over a 48-hour period the price of Nickel soared by 250 percent. The entire Bloomberg Commodity Spot index leapt 13% in a week — the largest one-week price increase in 60 years. If you were on the wrong side of those price movement you were in serious trouble. Little wonder, perhaps, that hedging the risks became very expensive.

The scale of the stress becomes more apparent when one appreciates that global commodity markets involve an annual volume of at least 700 billion dollars in buying and selling, plus trillions in derivatives piled on those trades.

At the most simple level the price of buying a typical oil cargo of 2 million barrels surged from $140 million to $280 million. That involves raising more money in funding.

Since its earliest beginnings international commodity trade has been interwoven with finance. And commodity markets are also one of the places where derivatives were first put to use. If you take a long position on oil – spending $ 280 million on a shipment – what you want to hedge against is the possibility that its price might fall before you can deliver it to market. Those derivatives contracts have to be paid for. The trading house will generally only pony up a fraction of the price of the derivative, borrowing the rest from a bank or another source of funding. The cost of the derivative insurance will then be factored into the price that the trading house looks to sell for when it offloads the shipment of oil, nickel, gas ec.

Derivative contracts typically stipulate that if prices fall or rise beyond a certain point, implying a loss for the trading house that took out the hedge, the trading house must provide more of their own money to back the deal. Otherwise, the lender must fear that the borrower will simply walk away from the contract. That request for more cash in a leveraged deal is one of the most feared events in financial markets. It is known as a margin call.

That is what has been roiling commodity markets in recent weeks.

Take for instance the gas market as described by the FT.

Big commodity traders use derivatives to hedge contracts against price swings and lock-in margins. This typically involves selling futures contracts in Gunvor’s case linked to TTF, Europe’s wholesale gas price. As gas prices in Europe and Asia have soared, the losses on these contracts have increased, requiring Gunvor and other traders to make margin payments to brokers and exchanges. These losses from profitable positions will be offset once the commodities are sold, but in the intervening period margin calls can place strain on commodity traders, which are dependent on short-term credit lines from banks to fund their activities. “This cash flow mismatch can cause major liquidity problems,” said Craig Pirrong, a finance professor at the University of Houston. “And banks, for various reasons . . . may not be willing to extend credit sufficient to meet these liquidity needs …”

Peabody Energy, the world’s largest private coal producer, provides another example also from the FT. Despite surging coal prices it has been making a loss on its derivative hedges.

The contract agreed last year locked Peabody into a sales price of $84 per metric tonne until mid-2023 for a fraction of its seaborne thermal coal production in Australia. Soaring prices now means that it has been hit with a margin call of more than $500mn. In response, it has turned to Goldman Sachs which has extended a $150mn credit facility to help bolster its liquidity at a juicy interest rate of 10 per cent. That move is controversial, given Goldman’s previously announced aversion to coal companies. … Peabody’s hedge was mercifully limited to just about a tenth of its thermal seaborne production. As the company sells unhedged coal at high spot prices over time, it will generate the resources to both fund any impending margin calls and pay down the Goldman loan. Peabody, like all other commodity producers, has been caught off guard by the rally in prices. Its ordeal is a reminder that companies favour predictability over volatility.

Peabody’s hedge was for a limited volume of coal and as a producer it has a massive structural long position from which it currently profits. It will earn its losses back and more. Large trading houses are not in such a comfortable position. They trade billions of dollars per week and have not natural hedge against surging prices.

Normally the initial margins they have to put down to secure a derivatives hedge are no more than a few percentage points of the underlying instrument. But in recent weeks they have had to offer as much as 80 percent of the money down.

One trader, used to margin calls or reductions of €50mn during normal volatility, is now looking at ten times that within a single day.

Across the range of major trading houses the pressure of margin calls and rising demands for cash have amounted to tens of billions of dollars. At that point the financial issue becomes serious.

The business is discreet. News of a margin call is like rumors of a fire in a crowded theater. None of the major players likes to admit that it might be under pressure. But the telltale signs are there.

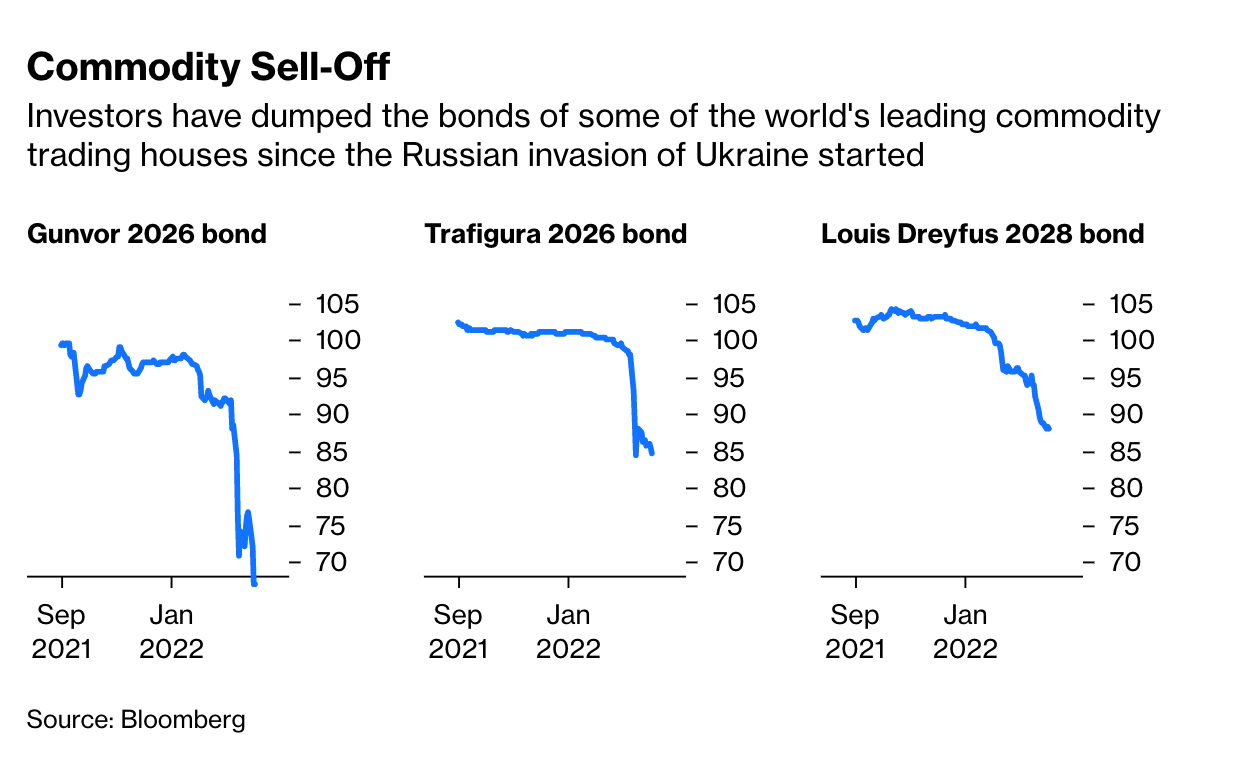

One marker is the price of debt issued by major trading houses. As commodity prices have surged the value of IOUs issued by the major companies that deal in commodities have plunged.

Several major players have found themselves acutely short of cash. The collapse of huge Chinese short positions in nickel has made global headlines, but humble European gas utilities are in trouble too.

A number of stories have circulated around Trafigura, one of the biggest players in the commodity market with a particular niche in dealing in the oil supplied by Rosneft.

In search of funding Trafigura has been in negotiations with private equity mega group Blackstone Inc. After that fell through it has approached Apollo Global Management Inc., BlackRock Inc. and KKR & Co. It seems to be looking for capital to the tune of $2 billion to $3 billion, which gives one an idea of the margin calls it has faced.

Trafigura also recently refinanced a $5.3 billion revolving credit facility, plus a new facility to the tune of 1.2- $2 billion. All told Trafigura according to its most recent annual report has credit lines to the tune of $66 billion with 140 banks.

Trafigura is a big player, but is it large enough to be systemic?

Owned by 1000 partners and recording profits of $3.1 billion, Trafigure would seem to be properly ranked not alongside a major commercial bank, or a Lehman-style investment bank, but in the midfield of hedge funds. Of course, of late, they too have been the beneficiaries of central bank intervention. But Trafigura does not look like another Lehman, whose short-term repo book in 2008 was numbered in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

In any case, a financial failure like that of Lehman, may not be the main threat in commodity markets. The main issue is the functioning of the market as such.

As the bigger players like Glencore Plc, Cargill Inc., Vitol Group and Trafigura Group are squeezed an even more intense pressure is applied to smaller players in the market. Their response is to pull back from the market altogether. That interrupts the smooth operation of offers for sales and bids to buy. The result is a surge in volatility and erratic price movements, which causes the larger houses that might still be able to raise finance, to pull back from the market. The overall result is that the market threatens to seize up altogether, as has happened in nickel.

As the FT reports:

In private, industry executives acknowledge they are skipping some deals to conserve cash. Lots of the price volatility of recent days can be traced by trading houses and others avoiding taking positions. The commodity market is trading risk, rather than supply and demand fundamentals. Liquidity is thin. …. Gunvor, one of the world’s biggest independent energy traders, cut trading positions after the gas price spike triggered margin calls from brokers and exchanges. The Geneva-based company reduced its exposure as wholesale gas prices surged over the past couple of months because of concerns about tight supplies ahead of the winter, said people with knowledge of the situation. The company, which has a significant European gas book, had received about $1bn of margin calls — demands for extra cash to cover its position, the people said.

This is the background against which the European Federation of Energy Traders wrote its letter of March 8th appealing for central bank intervention, to offer lender of last resort facilities to major commodity traders.

The EFET includes players like BP, Shell and commodity traders Vitol and Trafigura. What they asked for was “time-limited emergency liquidity support to ensure that wholesale gas and power markets continued to function. … Since the end of February 2022, an already challenging situation has worsened and more [European] energy participants are in [a] position where their ability to source additional liquidity is severely reduced or, in some cases, exhausted”. As a result it was “not infeasible to foresee . . . generally sound and healthy energy companies . . . unable to access cash”, the letter warned. People familiar with the matter said EFET members had raised the issue with central banks.

The EFET proposes that the European Investment Bank or central banks, such as the European Central Bank or the Bank of England, should provide support to lenders so that they do not need to intensify their margin calls on commodity traders.

“The overriding objective is to keep an orderly market for futures and other derivative energy contracts open,” said Peter Styles, executive vice-chair of the EFET board, in an interview. “Gas producers, European gas importers and power suppliers must retain the opportunity to hedge their positions.” Styles said it was possible to hedge risk without exchanges, but added that market participants needed the “liquidity, depth and visible price signals which futures exchanges with central clearing provide”.

So far Europe’s central bankers have been tight-lipped. Offering liquidity in the name of market functioning sounds laudable, but in practice what it means is providing a safety net for highly speculative, leverage commodity firms. Nevertheless, ECB vice-president Luis de Guindos has confirmed that the bank is closely monitoring derivatives markets. And it remains true that the banks involved in commodity lending can secure lender of last resort support from their central banks in any case.

The threat that markets might cease to function is, of course, alarming. And if it became a prolonged impasse it would have dramatic impact on the world economy. As Lex opines:

Financial risk aversion is applying a chokehold to oil supply chains that are already severely disrupted. This hardly benefits democracies intent on squeezing Russia via sanctions while improving energy security.

As Javier Blas of Bloomberg reminds us in a typically excellent op ed, the question of the systemic importance of commodity markets to the global financial system is not new. I was already put back in 2012 by Timothy Lane, then deputy governor of the Bank of Canada.

“Could the failure of one of the large trading houses cause serious disruption in the commodities markets?,” he asked in a speech in September 2012, arguing their size raised “the possibility” they were “becoming systemically important.”

Blas himself is skepical:

I have long argued that commodity traders don’t matter to the global economy in the same way that Lehman Brothers did: the collapse of one won’t trigger a global recession. And yet, they remain too big to be ignored — and a possible source of big trouble if left unattended. …

What if (the crisis in nickel had not been confined to nickel)?

What if, instead, it had been a large commodity trading house, and not just in nickel, but across a dozen markets? And what if the commodities affected were not nickel, but rather oil, natural gas, electricity, or, God forbid, wheat and other food staples? That may not be as bad as a Lehman-induced recession but would still be a gut-punch for the global economy.

Professor Craig Pirrong, interviewed by the FT concurred with Blas’s judgement. A liquidity squeeze on the commodity markets would lead major traders to cut positions. “This hurts, but it is not Armageddon.”

And the risk has been further reduced, as Blas remarks, by the fact that

The number of banks providing commodity-trade finance in large size has shrunk significantly over the last decade, particularly with the departures of one-time industry leaders BNP Paribas SA and ABN Amro Bank NV. Today, the traders rely on the likes of ING Groep NV, Credit Agricole SA, Unicredit SpA and a handful of other largely European banks. Several scandals, including the collapse of Singaporean oil trader Hin Leong last year, have prompted many banks to scale back their lending to the sector or even exit completely. … The result is an industry that has fewer doors to try in a crisis. … In public, all commodity traders, small and large, say everything is fine. Talk to executives in private, however, and the anxiety is plain — that their industry is one accident away from trouble. For now, we aren’t there, but central banks and policy makers should prepare for that eventuality.

And surely we have to ask: Why do the technicalities of financing energy trades matter?

What is at issue in the current moment is not the stability of the financial system as such, or the survival of particular trading houses, but the general sense of crisis and instability. Along with the war in Ukraine, the extreme spikes in oil and gas prices are a major manifestation of that instability. If there is a relevant lesson from Lehman in this context it is less a matter of financial technicalities than the realization that in a precariously balanced situation it can be very dangerous to let a major domino fall. And right now, the European gas market, is a very big domino indeed.

Another lesson from Lehman is that once the crisis has passed you must engage in wholehearted structural reform. The window of opportunity is narrow. And if you do not seize it, the structures that generated the risk in the first place will resume their growth and their vice grip on the political economy will become ever firmer.

If commodity businesses are part of the shadow banking ecosystem they too should be included in a major new regulatory push, drawing the lessons from 2020-2022.

****

I love writing Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.

In “normal times”, when the newsletter is not going out practically every day, paying subscribers receive regular Top Links emails with interesting, entertaining and beautiful reading and viewing. Let us hope for the return of more normal times soon.

In the mean time, please share Chartbook with your friends.