There is a changing of the guard in Beijing. Premier Li Keqiang is retiring and Vice Premier Liu He cannot be far behind. Once they were Xi’s point men on the economy. They leave the main stage amongst considerable turmoil.

Ukraine has thrown Xi’s geopolitics off balance and rallied the United States and its allies.

The dramatic transition in China’s domestic economic policy is continuing to cause a major shakeout. Last year China was dealing with an energy crunch. Now growth has slumped in Q4 2021 to 4 percent. For a few months the US actually grew faster than China.

The mood in the stock market is further worsened by rumors of impending fines to be levied on leading Chinese tech firms and an alarming surge in Omicron cases in Shenzhen and Shanghai, the heart of China’s manufacturing economy. Huawei, Oppo, TCL, Foxconn and Unmicron – key nodes in the smartphone supply chain – are all based in the zone affected by COVID lockdowns. The sanctions imposed on Russia are an alarming indicator of what might lie ahead in a future clash between China and the West.

The impact on the stock market has been brutal.

This thread by Rebecca Choong Wilkins vividly described the “carnage” in the Chinese markets earlier this week.

It’s carnage in Chinese markets today. These four charts show just how ugly it’s getting. 🧵 1/5

— Rebecca Choong Wilkins 钟碧琪 (@RChoongWilkins) March 14, 2022

By Monday March 14th the collapse in Chinese tech stocks amounted to a rout.

The China tech sell off continued in a big way today with new Covid lockdowns and regulatory crackdowns.

— Dani Burger (@daniburgz) March 14, 2022

Now the entirety of publicly-listed Chinese tech is worth less than Amazon.

h/t @DavidInglesTV pic.twitter.com/pEaWI4aQGO

It is cold comfort under these circumstances that Chinese trade with Russia surged 38.5% on the year in January and February, far outpacing Beijing’s 15.9% increase in total trade for the period.

Since the Central Economic Work Conference in December 2021 the talk in party circles has been of the “triple pressure” facing the Chinese economy, ranging from weakening expectations, shocks to supply, and a contraction in demand.

But to get a grip on China’s current situation, let us wind the clock back a little further, to the “before times”.

Remember January 2019 when Xi was warning officials to beware “grey rhinos” – the threats that become so familiar that we actually end up ignoring them – as well as truly unexpected “black swans”? Risk management was the order of the day for cadres. Xi warned that they faced “changes not seen in a century”.

Remember the “Six major effects” driving heightened global risk identified by CCP-thinker Chen Yixin in 2019 – Backflow, Convergence, Layering, Linkage, Magnification, Induction?

COVID was a classic grey rhino. But so too are the consequences of China having adopted a no-covid policy in a world which unlike China went the route of herd immunity and vaccination. It should not be surprising that Beijing now finds itself backed into a corner.

What is surprising is the failure to properly vaccinate the elderly population in a city like Hong Kong.

NEW: I’m not sure people appreciate quite how bad the Covid situation is in Hong Kong, nor what might be around the corner.

— John Burn-Murdoch (@jburnmurdoch) March 14, 2022

First, an astonishing chart.

After keeping Covid at bay for two years, Omicron has hit HK and New Zealand, but the outcomes could not be more different. pic.twitter.com/1Ol4HHs9kT

And the situation on the mainland is only little better. Omicron poses an acute risk to the vulnerable, unvaccinated and immuno-naive elderly population of China. Hong Kong is currently setting a record for a surge in mortality. Worse might be about to follow. Imagine the deaths in the nursing homes of England or New York State, multiplied ten times or more.

Earlier I warned about what might yet be around the corner.

— John Burn-Murdoch (@jburnmurdoch) March 14, 2022

Aside from Hong Kong itself, where the surge in cases in recent days is sure to have locked in hundreds more deaths, the looming crisis is mainland China, where elderly vaccination rates are only slightly better than HK pic.twitter.com/CsHW6UWWV7

The threat posed by China’s real estate bubbles has long been discussed and the challenge posed by the tech oligarchs was no secret either. These are the kind of crises that the West has regularly sleepwalked into. In this regard China’s regime is impressive precisely for the fact that it is acting in anticipation of emerging threats.

To prick the bubble is risky. It certainly isn’t good for stock markets, or growth figures. But you have to appreciate Beijing’s strategic foresight in deciding that it was time to do something about dangerous developments that were headed in the wrong direction.

The clash with the US too is no black swan. It was long foretold. It is predictable that China’s aggressive diplomacy should has unleashed a reaction from Washington. But it is not obvious what kind of diplomacy on China’s part could have avoided an eventual confrontation. To avoid antagonizing the Pentagon, China’s defense spending would have had to have been continuously reduced as a share of GDP.

Faced with the likelihood of an escalating confrontation with the US, an alliance with Russia looked like a good option. It added strategic depth, raw materials and energy supplies. It wasn’t Xi who cooked up the idea or the wolf warriors. It is an option that both China and Russia had been exploring since the 1990s.

What neither Beijing or anyone else truly reckoned with was Putin’s willingness to launch an all out invasion. Geopolitical tension over Ukraine was to be expected. China’s backing for Russia helped to foster it. But all out war with all its attendant risks is another matter altogether. From Beijing’s point of view, Putin’s extraordinary decision is no doubt a major shock.

Did China help to encourage Putin, if so that is a case of what Chen Yixin dubbed “backflow”.

In global opinion it has induced induction and magnification effects even more dramatic than the BLM moment. Ukraine has become a global symbol of popular resistance and self-empowerment.

Given the huge swing in global public opinion against China in the wake of COVID, the last thing Beijing needs is to be associated with a blood soaked and repressive Putin.

Furthermore, Russia’s aggression has rallied a coalition of hostile forces – convergence, layering and linkage in Chen Yixin’s terms.

As Gideon Rachman remarks in the FT:

The fact that the EU, UK, Swiss, South Koreans, Japanese and Singaporeans have joined in the financial sanctions on Russia has created a united front of developed economies that should concern Beijing. China has repeatedly measured itself directly against the US, ticking off milestones as it goes: largest trading power, largest economy measured by purchasing power, largest navy. Yet if China now has to measure itself against not just the US, but also the EU, UK, Japan, Canada and Australia, its relative position looks much less powerful. … The idea of an economic severance of China from the west, once unthinkable, is beginning to look more plausible. It might even appeal to the growing constituency of economic nationalists in the west who now regard globalisation as a disastrous error.

To exert pressure on Russia, the Western coalition has deployed its most dramatic weapon – a targeted attack on Russia’s national currency reserves.

The move against Russia’s fx reserves is a surprise. But, as far as China is concerned, this too ought to be considered a grey rhino rather than a black swan. Though the extent of the measures against Russia is certainly surprising, it has long been discussed that China will have difficulty escaping the grip of the dollar. Add the Europeans and you have a “Western bloc” that monopolizes 80 percent or more of reserve assets. A country like China that has used giant export surpluses to drive a lopsided pattern of growth will, in the end, find itself boxed in.

This is compounded by the entanglement of Chinese business with western financial markets and the dollar system. It was telling that President Xi Jinping’s in his address to the WEF in January warned Western economies not to “slam on the brakes or take a U-turn in their monetary policies.” A sudden tightening of US policy would squeeze the entire global economy. In light of the recessionary tendencies inside China, it would be most unwelcome in Beijing.

Russia faces a Eurodollar trap. China has to contend also with the pivotal role of Japan’s financial system as a conduit for dollars into the East Asian economy.

As Andrew Hunt and Ben Ashby write in Nikkei Asian Review, Japan’s megabanks perform a “vital but little understood function” in supplying dollars to the Asian economy.

Despite the growth of China’s banking system, much of it remains domestically focused. China’s banks also lack the creditworthiness and international connections that Japan’s financial institutions enjoy.

With the financing of much of Asia’s trade and the flows in and out of its various financial centers still heavily dependent on Japan, Japan’s bankers, squeezed between an overheating U.S. and an increasingly troubled China, have a difficult balancing act to perform…..

With the Fed now worried about inflation, likely to lead to a tightening of global liquidity, Japanese banks must now make some tough decisions over what to do with the more than $5 trillion worth of overseas claims they have amassed.

Do they cut back on risk and reduce their Eurodollar borrowing, charge a higher interest rate to borrowers, or become more selective in their lending? Our guess is that they will do a mixture of all three.

With $166 billion of direct exposure to mainland China and Hong Kong, and with huge problems beginning to surface in Chinese real estate, this sector will be a prime candidate for risk reduction. It will be a difficult balancing act and, if Tokyo’s bankers do not pull it off, it may add to China’s own problems at an already difficult time.

The Ukraine crisis has seen Japan aligned squarely with the United States. Rising tension with China points in the same direction.

As far as Beijing is concerned, Minxin Pei writing in Nikkei Asia Review comes to a bleak conclusion.

For China, which might have benefited from a prolonged period of tensions between Russia and the West, the paths ahead have suddenly become far more treacherous. Instead of being a net beneficiary of a conflict between Russia and the West, China now finds itself perilously close to being collateral damage. While the crippling economic blows against Russia are applauded in the West, Chinese leaders watch them with great alarm. Their country is far more economically tied to the West than Russia is. Although the same type of economic sanctions leveled at Russia would unavoidably hurt Western economies, they could be catastrophic for China in the event of a war across the Taiwan Strait.

But talk of Beijing becoming collateral damage seems exaggerated.

Ukraine is ultimately a European problem. A prolonged period of high tension between the West and Russia will be hard for America and its allies to sustain. It will be surprising if the current sense of purpose in the West endures.

The domestic problems of the Biden administration continue and will likely intensify in the course of 2022. His nominations for the Fed board are in trouble along with the rest of his domestic agenda.

Whether Europe will actually back decisive action against Russia remains to be seen. In Germany there are huge political obstacles to taking decisive steps against Russia. Whatever the EU decides to do, it has a bona fide energy crisis to deal with.

No doubt Russian energy is hard to do without, but it if can hold its nerve, Beijing might well conclude that there are limits to the kind of economic pressure it should expect.

Furthermore, the G7 front against Russia does not negate the basic diagnosis of growing multipolarity. In abstaining on the UN vote of censure against Russia, China had the company of India and governments representing more than half the world’s population.

With relations between Saudi Arabia and the US frosty, Xi is weighing an invitation to meet with MBS in Riyadh in April. Whatever Europe and America’s concerns, it is China remains the world’s number one fossil fuel importer and that earns it respect.

And if you turn the gaze back to the US, the fact remains – as discussed in Chartbook #94 – that the US does not truly have a policy to offer in the Indo-Pacific strategy. It has published a blueprint. But is concerns are overwhelmingly domestic – fashioning a trade policy that is acceptable to America’s “middle class”. Whether that will suit any major partners in Asia is another matter altogether. The war in Ukraine is not going to persuade major Asian players that their future belongs in an anti-China camp masterminded by Washington. They do not want to have to choose.

Ultimately, what matters most is that China sustain its position as the leading driver of global economic growth. It needs to be better balanced in economic, social and environmental terms. That will tend to reduce the growth in China’s appetite for raw materials and industrial components. But it may result in even larger and more diversified imports from the rest of Asia.

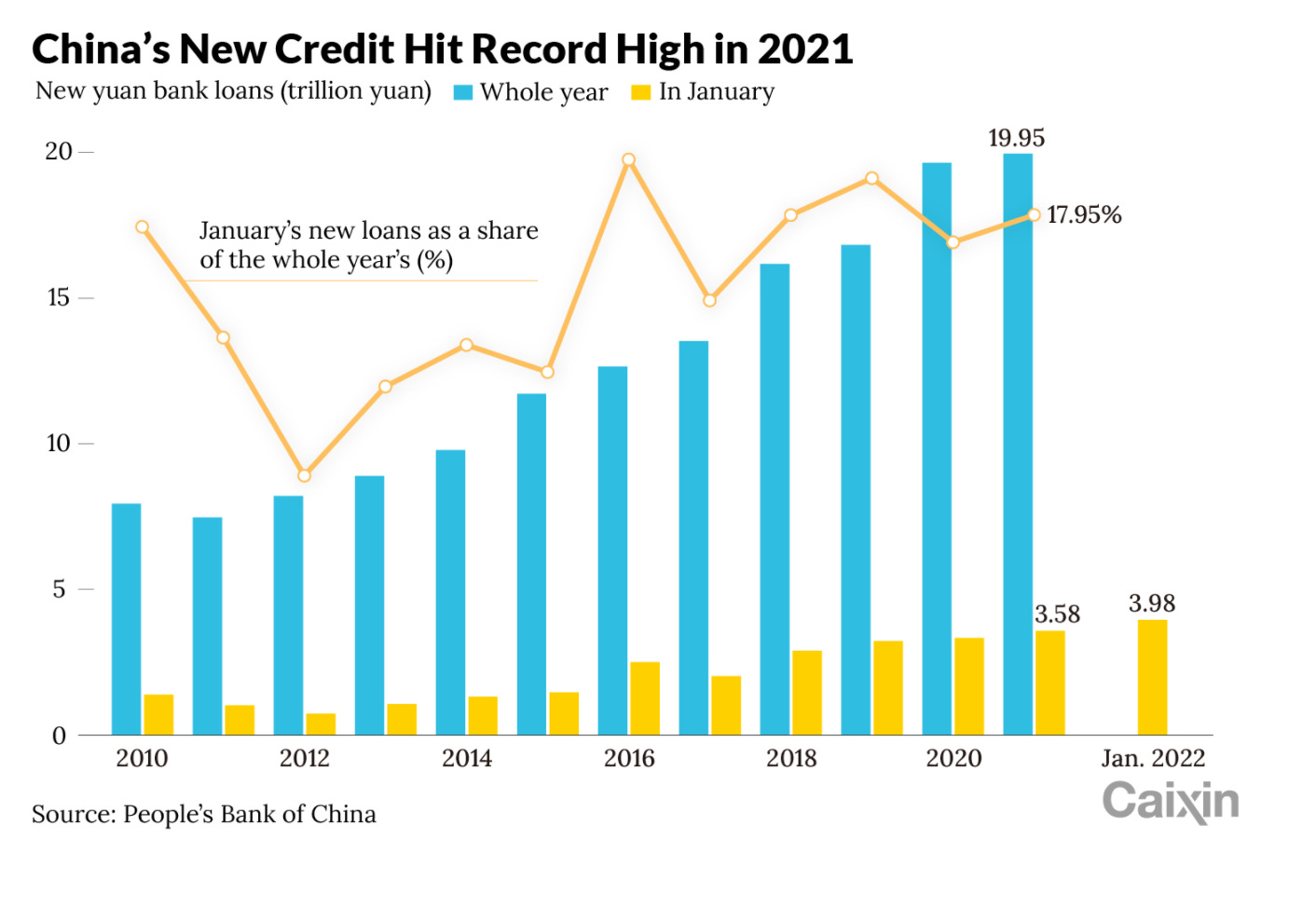

What Beijing is currently planning to stimulate its economy seems to be a blend of different policy tools. It is expanding social credit, the basic driver of demand. New total social financing hit a record high of 6.17 trillion yuan in January, beating market expectations of around 5.4 trillion yuan. New bank loans also rose to a record high of nearly 4 trillion yuan in January. But the February numbers were disappointing, indicating how much work Beijing may need to do to hit its growth target of 5.5%.

On January 18 Liu Guoqiang, a deputy governor of the PBOC promised that the central bank will “open the monetary policy toolbox wider, maintain stability in the money supply and avoid a collapse in credit.”

As in 2012, 2016 and 2019 one analyst noted, Beijing is in a “race between slowdown and stimulus”. But the real challenge for Beijing is to find new sources of growth.

Authorities in recent months have rolled out cash subsidies for high-end manufacturing, affordable housing and sustainable energy. Not all Chinese stocks are selling off. So-called Chinese red chips — Hong Kong-listed Chinese companies with significant state control — climbed 20% in six months. Since Xi pledged in late 2020 that China would hit carbon neutralityby 2060 renewable energy funds have in some cases returned more than 40%.

The regime is clamping down on excessive lending in private real estate, but at the same time the government had announced plans to build 6.5 million low-cost rental apartments by 2025. If this is realized it will mean that an estimated 26% of new home supply will be offered at 30% below the market rate. In early February lending for such projects was exempt from limits on property lending, prompting talk of the “next big thing”.

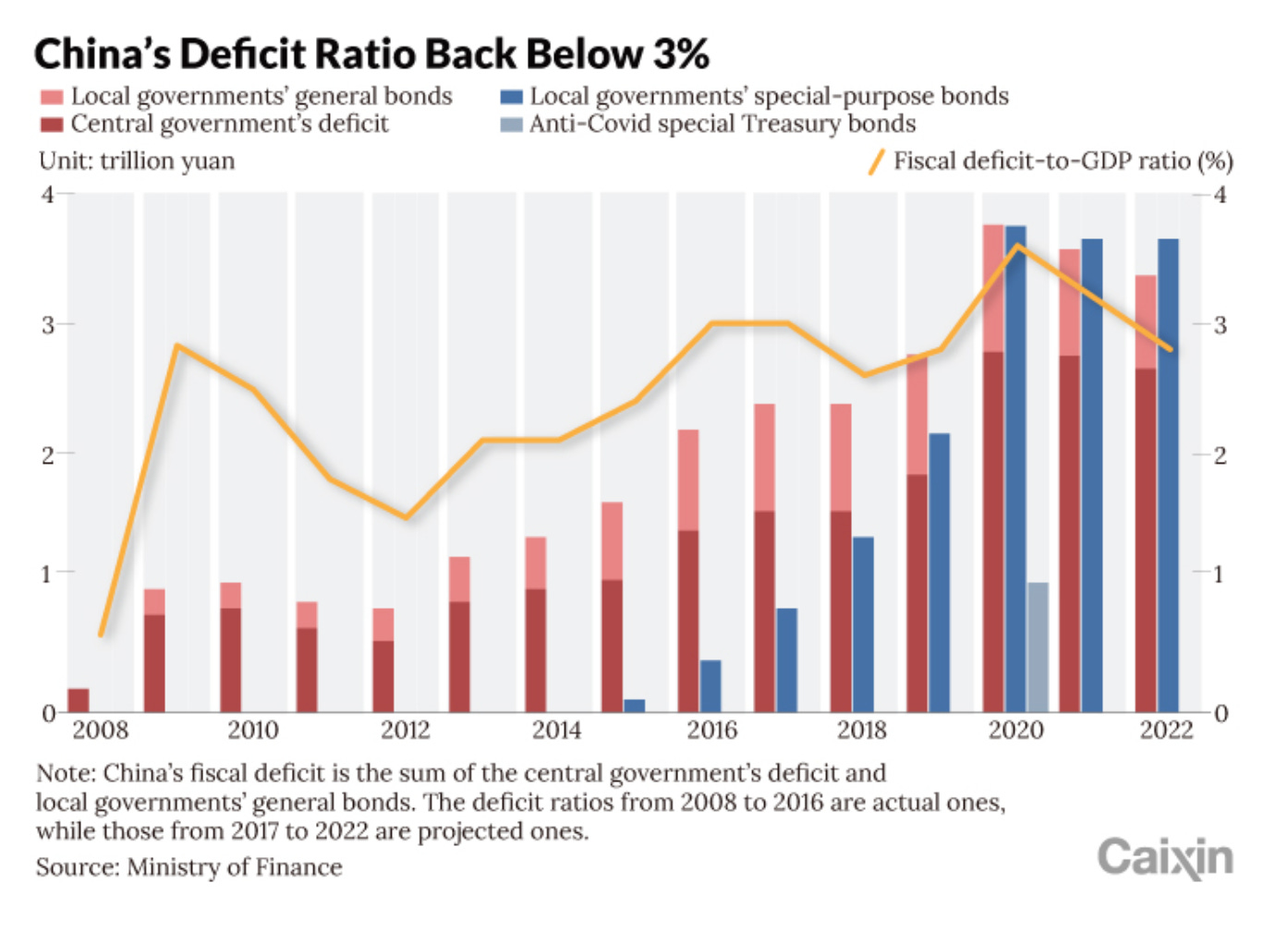

The annual Two Sessions closed last week with a commitment to a 5.5 percent growth rate. If realized this will be well below the growth in public spending which is expected to rise by 8.4 percent and result in a deficit of just below 3 %.

Source: Caixin

Within Chinese public expenditure, infrastructure investment will continue to play a key role, with central government expenditure rising by 5% to 640 billion yuan. But on top of that the central government will transfer 9.8 trillion yuan to local governments, up 18% from 2021, much of which will go towards funding investment spending.

This frankly sounds like relatively marginal adjustments to the familiar growth formula. How far “common prosperity” is really a comprehensive new formula and new vision of growth remains to be seen. But that is truly the decisive question also as far as China’s global standing is concerned.

Putin’s attack on Ukraine has shifted the international balance. It has, to say the least, not been a success for Russia so far. In a protracted struggle with the West, Russia might still end up sliding into China’s more or less reluctant embrace. But China won’t rush to take up that role and it will surely guard against getting sucked into a further escalation of US sanctions. What is clear, is that above all its future depends on facing domestic challenges both in the medium and the short-term.

If Beijing suffers a devastating Omicron outbreak in the next few months the entire narrative of the period since 2020 will have to be rewritten.

***

I love writing Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.

In “normal times”, when the newsletter is not going out practically every day, paying subscribers receive regular Top Links emails with interesting, entertaining and beautiful reading and viewing. Let us hope for the return of more normal times soon.

In the mean time, please share Chartbook with your friends.