Like most folks I’ve been staggered by how rapidly the West has escalated the economic war against Putin’s regime.

But, we must remind ourselves that energy remains the giant exception.

In the oil market, there are reports of “self-sanctioning” by Western firms, which is making it harder for Russia to sell its oil. I have not yet seen any overall estimate of the effect in reducing oil revenue flow. Is there one out there?

The overall figure matters, because in gas the flow continues unabated and, with European customers now paying even more exorbitant prices, Russia is benefiting from a staggering surge in revenue. According to Javier Blas of Bloomberg, at the start of the year, Russia was earning $350 million per day from oil and $200 million per day from gas. On March 3 2022 Europe paid $720 million to Russia for gas alone.

Below, Russia's 2021 income from its EU export of gas not listing its income from our import of Russian oil. If we would not buy this Russian pipeline gas & oil, Moscow couldn't easily divert the enormous volumes to other markets. It lacks an alternative transport infrastructure. pic.twitter.com/6zwGhJTYnT

— Andreas Umland (@UmlandAndreas) March 5, 2022

Unless the oil revenues have collapsed, any self-sanctioning effect is likely to have been more than offset by the huge surge in gas prices.

Sanctions clearly are biting, however. And the central bank measures are the most decisive so far. As Florian Kern of the Dezernat Zukunft, the macrofinance think tank in Berlin, spells out in this brilliant thread, BOTH Russia financial claims AND its gold are effectively inaccessible at this time. In a war, there is no “outside money”.

Zoltan Pozsar is one of the world’s most respected money market specialists and predicted the repo crisis in September 2019. Here he is getting it wrong, as he misses key aspects about the gold market and MoPo implementation in his analysis (1/18)🧵 https://t.co/V7dzBiHmbM

— Florian M. Kern (@FlorianMKern) March 3, 2022

The sanctions on the central bank have effectively forced the imposition of an exchange-control regime in Russia. A non-exhaustive list of measures taken so far includes

(1) Fees on exchange transactions: up to 30% commission according to Jack Cordell.

(2) “Blocked” rouble accounts into which Russian debtors repay their foreign loans without the debt service being transferred. (Very reminiscent of 1920s and 1930s Germany).

(3) $5000 per month limits on conversion of rouble into western currencies.

Would love to know of more, if someone has a complete list.

This tweet from the arch Brexiteer Rees-Mogg was unintentionally revealing about where Russian wealth was most concentrated before the crisis. British talk about money laundering aside, the City of London is doing its thing as a global financial entrepôt.

The City of London leads the way in the effects of sanctioning Russian banks. pic.twitter.com/WAgFV64ghy

— Jacob Rees-Mogg (@Jacob_Rees_Mogg) March 5, 2022

On top of official sanctions , self-sanctioning by Western firms are leading to a cut off of services and supply in many critical areas. We should no doubt expect this to escalate, “tit for tat” (though there is clearly no equivalence in the means at the disposal of the two sides).

Asset freezes of the respective counties’ businesses might be the natural next step of Russia’s counter-sanction. https://t.co/zwAnGWQDt7

— Elina Ribakova 🇺🇦 (@elinaribakova) March 6, 2022

In Chartbook #91 I raised the question of how far Russia might be able to offset these blows to the home front through a more creative, expansionary economic policy. In researching that question I stumbled on the fact that the “MMT”-meme had in fact been part of the policy debate in Moscow in 2018-9 and at least one of Putin’s key advisors played a role in instigating that debate.

My two favorite responses to #91 were by Daniela Gabor (great thread on the options for the developmental state)

fascinating @adam_tooze on whether we'll see Russia abandon its Wall Street Consensus macrofinancial regime – fiscal austerity, floating exchange rate, domestic bond finance – that it deployed to accumulate a foreign reserves war chest. https://t.co/qoIdmDah2y

— Daniela Gabor (@DanielaGabor) March 4, 2022

And, Nick Trickett, an essential follow, who gives a brilliant, downbeat analysis of the realities of Russian fiscal policy.

Some thoughts on the latest @adam_tooze chartbook regarding MMT and Russia. Needless to say I’m happy that’s where the conversation is turning given it was a bugbear of mine throughout COVID just how much fiscal space the regime had and yet refused to make use of.

— Nick “in media MinRes” Birman-Trickett (@ntrickett16) March 4, 2022

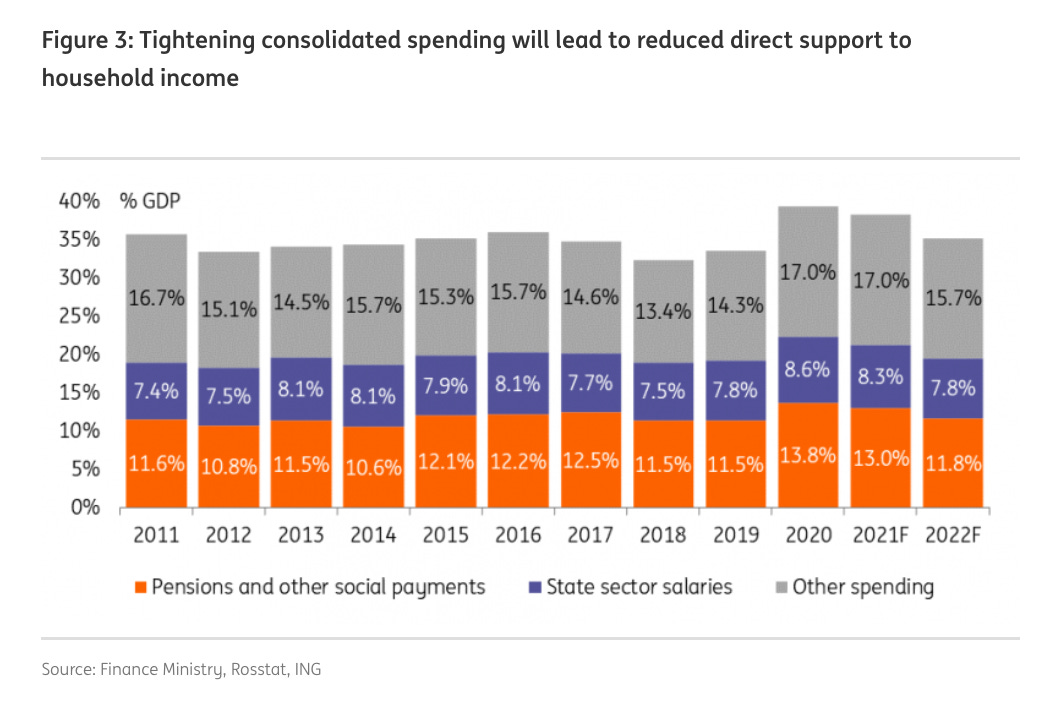

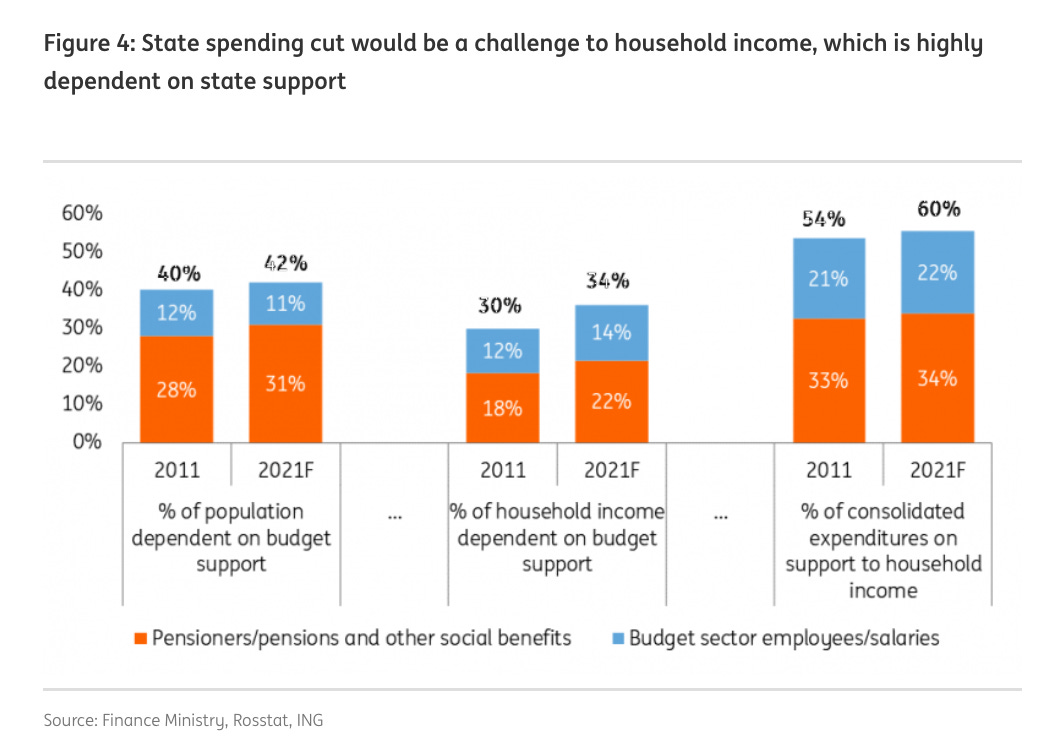

In part, my speculation about unchaining a Keynesian/MMT response to the shock in Russia was driven by reading Dmitry Dolgin’s analysis of the Russian economy at ING. His analysis often draws on rather interesting data on the share of Russian budget and household incomes that derives form state sources.

What fiscal measures have the Russians actually taken so far? Alex Nice is running an outstanding thread on the economic side of the conflict. He catalogues a list of fiscal measures and indexation of pensions etc. Predictable stuff. No Russian Rescue Plan so far.

159/ Duma passes packet of anti-crisis measures in a day, following the Covid playbook: moratorium on business checks; capital amnesty; powers to ministers to give biz support and increase social payments; Rb1trn from Wealth Fund used to buy gov debt… https://t.co/kGyNCjgtc6

— Alex Nice (@AlexNicest) March 4, 2022

If ideology does not get in the way and the Russian state has the capacity through its reformed tax system to deliver a boost in nominal incomes to a large slice of the population that may offset some of the immediate hurt from sanctions. Think of the effect of stimulus checks in the US during COVID. A fair portion wasn’t spent. Couldn’t be spent. But the checks made people feel less insecure and helped them pay down credit card bills.

Clearly, however, if supply constraints are massively binding that will limit the effects you can achieve even with an active monetary and fiscal policy. More money won’t save your military sector from running out of vital components (as emphasized by Yakov Feygin) and it wont keep your airplanes in the sky if you don’t have the parts. So how bad will the squeeze be?

Production of complex goods with international supply chains – such as cars, planes etc – will be virtually impossible in Russia in the coming months. Russia's industry is coming to a standstill. It would be easier if Russia was a petrostate, but it isn't. https://t.co/0rkayvhEID

— Janis Kluge (@jakluge) March 3, 2022

This thread on the weaknesses of the Russian economy from the highly knowledgeable Kamil Galeev acquired huge momentum online.

Russian economy is super fragile. It's critically dependent upon the:

— Kamil Galeev (@kamilkazani) March 4, 2022

1. Export of natural resources

2. Technological import

It has always been so. That's why Russia could never win a major war without massive economic help of the West. Without Western allies Russia's doomed🧵 pic.twitter.com/0HEe4tnYAD

There are plenty of predictions of collapse out there:

Surprising honesty from Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska on the unraveling economic crisis: "This is going to be like 1998 crisis but three times worse and will last 3 years"

— Anton Barbashin (@ABarbashin) March 6, 2022

1998 was a full-blown crisis of the Russian state and Russian society. Is this a likely scenario. JP Morgan, for one, does not think so.

LONDON, March 3 (Reuters) – JPMorgan said on Thursday it expected Russia's economy to contract 35% in the second quarter and 7% in 2022 with the economy suffering an economic output decline comparable to the 1998 crisis.

— tom balmforth (@BalmforthTom) March 3, 2022

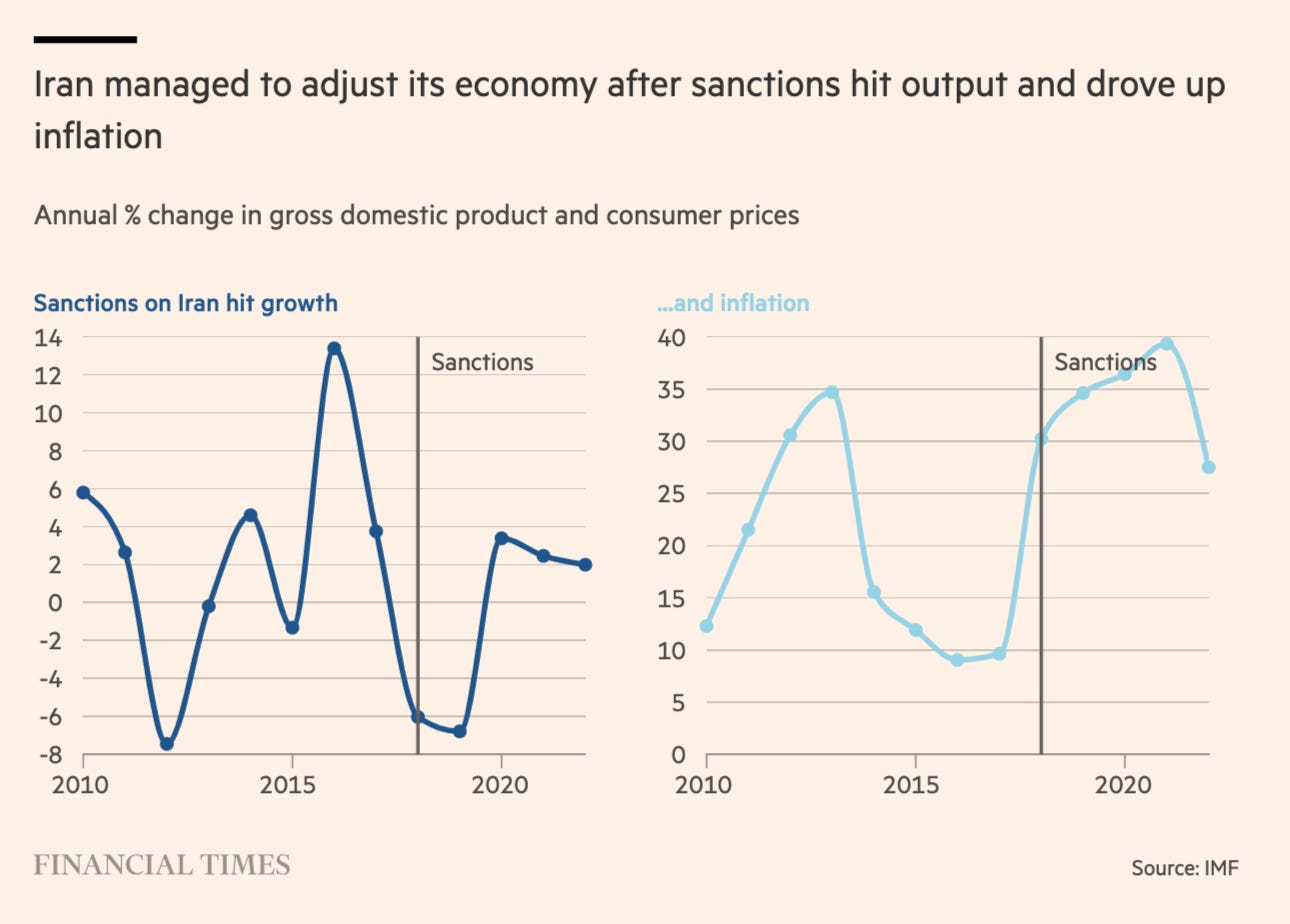

A lot of folks pooh-poohed the JP Morgan estimate. But those kind of numbers are the kind of figure suggested by Iranian experience – and the Iranian sanctions were more comprehensive and severe and hit an economy that was more fragile. As this excellent thread points out.

1. So @adam_tooze is right that sanctions on Russia’s central bank, freezing reserves would mean a full “financial war” similar to that waged on Iran.

— Esfandyar Batmanghelidj (@yarbatman) February 26, 2022

But the financial war didn’t “cripple” Iran’s economy. There is always a structural adjustment. https://t.co/giC1eI5h5k

The FT’s analysis of the impact of sanctions on Iran also refuses the apocalyptic reading.

Iran is still completely cut off from the world’s financial system, including the Swift payments network that now excludes some Russian lenders. Its economy has suffered significantly. IMF figures suggest that gross domestic product per capita sank 15 per cent across 2018 and 2019 and that Iranians will not regain 2016 levels of living standards until at least a decade later. Inflation, which hit 48 per cent at the end of 2018, is forecast to remain well above 25 per cent. But in a sign of the potential impact on Russia, Iran’s oil exports to friendly countries continue and the economy has not collapsed after decades of restrictions. Supermarket shelves are usually full, and petrol stations rarely suffer fuel shortages. Wealthier Iranians, many of whom have political ties to the leadership in Tehran, have maintained their luxurious lifestyles. “With a nuclear agreement, Iran can have 15 per cent economic growth,” said Saeed Laylaz, an Iranian analyst. “Without an agreement, if oil prices remain high and Iran can continue to sell 1mn barrels a day [of oil] or so, and with rises in taxation, it can run the economy and have [modest] growth.”

Why these numbers matter is brought home by this excellent thread on oligarchic politics by University of Toronto’s Olga Chyzh. If we are talking about power politics there are TWO questions that matter – the size of the cake AND how it is distributed.

The bottom line: The current sanctions decrease the size of the pie, but the pie is still very large and Putin’s ability to distribute it is intact. No other candidate would guarantee a similar distribution to the current players. 20/

— Professor Olga Chyzh (@olga_chyzh) March 5, 2022

On the politics of the “oligarch” group, Max Seddon Moscow bureau chief of the FT did a great thread, which concluded as follows:

This list shows you how much Kremlin Inc has changed since Putin came to power. You'd only call a handful of these guys, like Yevtushenkov, oligarchs in the classical sense. A lot of them are state company bosses with KGB pasts like Akimov and Sechin

— max seddon (@maxseddon) February 24, 2022