How will the confrontation in Ukraine affect the global balance? Specifically, how might it shift the balance between the US and China.

The immediate diagnosis seemed not to favor the US.

Largely unnoticed, into the escalating tension in Ukraine, on Friday February 11 the Biden administration launched its Indo-Pacific strategy.

It was in large part a placeholder document, especially as far as the economic sections are concerned.

As far as the economy is concerned the document gestures to a long-promised “economic framework” for the Indo-Pacific and anchors this in the common interests of the “middle-class” of the region.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made clear the need for a recovery that promotes broad-based economic growth. That requires investments to encourage innovation, strengthen economic competitiveness, produce good-paying jobs, rebuild supply chains, and expand economic opportunities for middle-class families: 1.5 billion people in the Indo-Pacific will join the global middle class in this decade. Alongside our partners, the United States will put forward an Indo-Pacific economic framework—a multilateral partnership for the 21st century. This economic framework will help our economies to harness rapid technological transformation, including in the digital economy, and adapt to the coming energy and climate transition. The United States will work with partners to ensure that citizens on both sides of the Pacific reap the benefits of these historic economic changes, while deepening our integration. We will develop new approaches to trade that meet high labor and environmental standards and will govern our digital economies and cross-border data flows according to open principles, including through a new digitaleconomy framework. We will work with our partners to advance resilient and secure supply chains that are diverse, open, and predictable, while removing barriers and improving transparency and informationsharing. We will make shared investments in decarbonization and clean energy, and work in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) to promote free, fair, and open trade and investment, during our host year, in 2023, and beyond.

But, as Bob Davis had pointed out in a cutting analysis in Polico, there is, so far, little substance to back up this rhetoric. And there is good reason for that impasse.

Asia doesn’t want an exclusively security-based alliance with the US. It wants a trade deal. But, for domestic reasons, the Biden administration cannot engage in an expansive trade policy. The mishandling of the “China shock” to the US economy in the late 1990s and early 2000s, has left a legacy that is too toxic in political terms. The failure to cushion the impact on key constituencies and the success of political entrepreneurs in turning it into a cause celebrate, now robs the US of trading off domestic and foreign policy objectives. Divisions within the Biden administration reflect the impact of that shock. It is an open secret that the big Asia-Pacific trade deal negotiated by the Obama administration would have been allowed to die even if Clinton and not Trump had been elected. The only trade/industrial policy that Congress is at all likely to approve is anti-China. An anti-China trade policy can also, perhaps, be sold as the “foreign policy for the American middle class” that the Biden team promised. The problem is that the Asian economies don’t buy the alignment of interests between the US and Asia-Pacific middle class conjured up by the White House document. But they are intensely interested in China. They have no interest in any substantial trade deal with the US that excludes China.

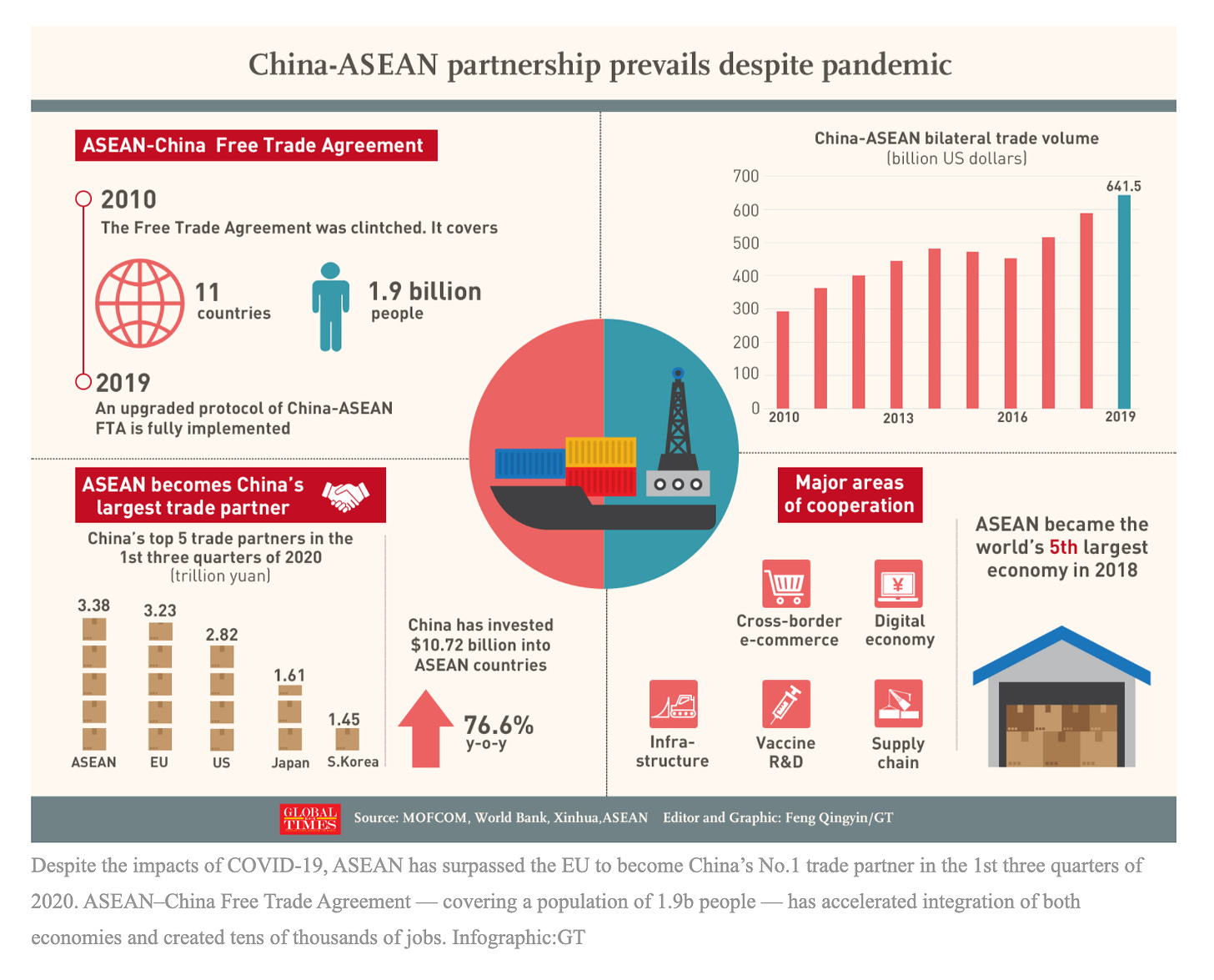

The balance in the Asian economy has tipped too far towards China already for any economic bloc formation against China to be attractive. As the Global Times gloating documents here:

Given its lack of substance, it is unsurprising that little has been heard about the Indo-Pacific strategy since its launch. But that silence is telling. One year after taking office, the US went into the Ukraine crisis with a void where a Indo-Pacific strategy ought to be. Any view to balancing China with a reset with Russia has clearly been blown apart. There is also no clearly articulated grand strategy for rallying the rest of Asia to contain China.

Instead, what has come to dominate the discussion is economic and financial warfare against Russia. The United States and Europe took the unprecedented step of placing the very large foreign exchange reserves of a fellow G20 member under sanctions.

In the days that followed, this triggered a rush of commentary about the end of the dollar hegemony. America and Europe’s actions were the assertion of an exorbitant privilege. Potential rivals would look for alternative homes for their reserves. Rana Foroohar in the FT stated the main links of the argument already on February 27.

All of this supports China’s long-term goal of building a post-dollarised world, in which Russia would be one of many vassal states settling all transactions in renminbi.

Pozsar doubled down on this claim on the OddLots podcast, even speculating about the emergence of new gold-backed rouble.

Frankly, this seems far-fetched, at least in the short-run. Rather than the dollar being displaced we are seeing the reverse.

Putin’s war has unleashed a shock of huge uncertainty. The result, as usual in such circumstances, is a rising dollar. From the lows reached in the summer of 2021, the dollar index has lurched upwards.

The situation is not helped by the elimination of 200 billion dollars worth of Russian funds from the short-term funding markets, which Pozsar identified and I discussed in Chartbook #89.

As Gillian Tett sagely remarked:

financial war, like the real variety, creates unpredictable aftershocks and collateral damage. It would be naive to think this will only hit Russian players.

Some funding stress did emerge in the first week of the war. But, as this excellent FT roundup by Kate Duguid, Joe Rennison and Colby Smith makes clear, there has, so far, been nothing like the crisis we saw in money markets in March 2020.

The main reason that there has been no panic is not only that the squeeze in funding has been modest, but also that there is no reason to doubt that the Fed can handle any pressure that does arise. As the FT team report.

When asked by US lawmakers on Wednesday about dollar funding markets, Jay Powell, the Fed chair, said they were “functioning well”. He said a “great deal of liquidity” was coursing through the system. “Between our swap lines and our repo facility for other foreign central banks and our standing repo facility in the Treasury market, we have institutionalised liquidity provision,” he said.

It is, of course, possible that funding stress may still escalate, but the Fed acts as a reserve stabilizing capacity and this is a key factor in the dollar’s ongoing attractiveness.

Hegemony isn’t a fixed, structural feature of the world. Hegemony is what you make of it. You produce and reproduce it at moments of crisis by acting promptly and at scale. The Fed has acquired a well-justified reputation as a generous hegemon of the dollar-based global system. Since 2008 it has repeatedly acted to ensure sufficient liquidity. Whether that is sustainable in the long-run, whether it leads to the progressive devaluation of the dollar, or a world awash with credit, these are serious. But right now they are not top of mind. In the long run – as Keynes famously said – we are all dead. And if we weren’t already aware of the wisdom of that message, President Putin has done his bit to remind us of it.

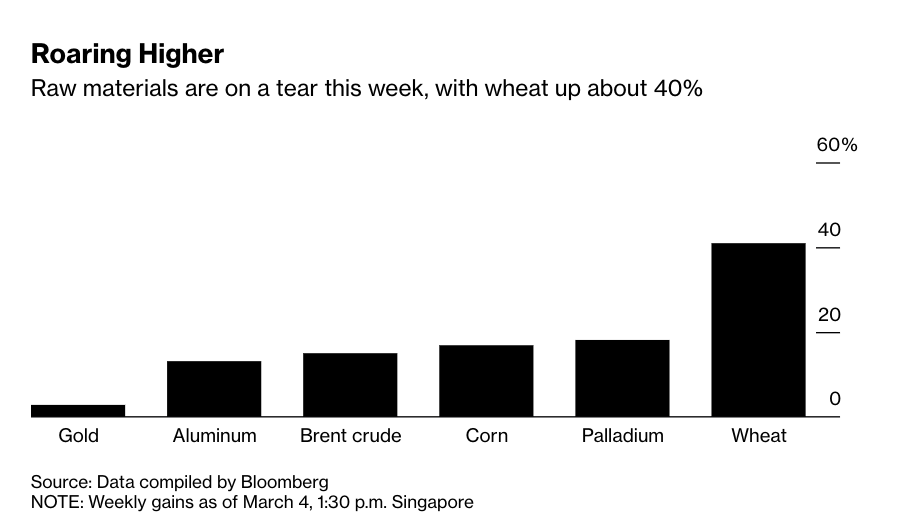

Meanwhile, global commodity prices are surging. Given current market conditions, why would exporters accept payment in something other than the most fungible currency i.e. dollars?

In the 1970s the oil price shock coincided with a crisis in confidence in the dollar. OPEC could be excused for questioning whether they should really accept payment for oil in depreciating greenbacks.

Today too there is inflation. But it is nowhere near as rapid as in the 1970s and rather than going hand in hand with a fall in the value of the dollar, we are seeing a rise. The markets right now want to see the Fed raise rates, but no one is calling for a Volcker shock.

Relations between Saudi and the Gulf states and the Biden administration are not easy. The Biden administration is so desperate to increase oil supply that it is even pushing for a deal with Iran. This will not please MBS. The Saudis have declared that they remain loyal to the OPEC Plus framework, i.e. the deal struck with Putin to end the oil price collapse of 2014-5. UAE abstained in the UN vote on Russia’s invasion.

But if cutting Russia off from its reserves has not fundamentally shaken the financial markets, an incremental move by the Saudis or other Gulf states to rebalance their portfolios away from dollars is not going to either.

Russia will presumably try to sell oil, gas, fertilizer, grain and perhaps gold from its reserves for something other than dollars. Or as Pozsar suggests they may repo their gold. But that will be a carved-out, stigmatized, sanctioned market. Ultimately, Russia’s only credible partner is China. And China has so far played a notably cautious hand.

It voted to abstain, not to veto the UN resolution. Today it is signaling the desire to mediate in the conflict and remarkably EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell has indicated that he would welcome that development.

Crucially, China has not thrown itself full-throatedly onto the Russian side as talk of a “no limits” partnership might have led one to expect.

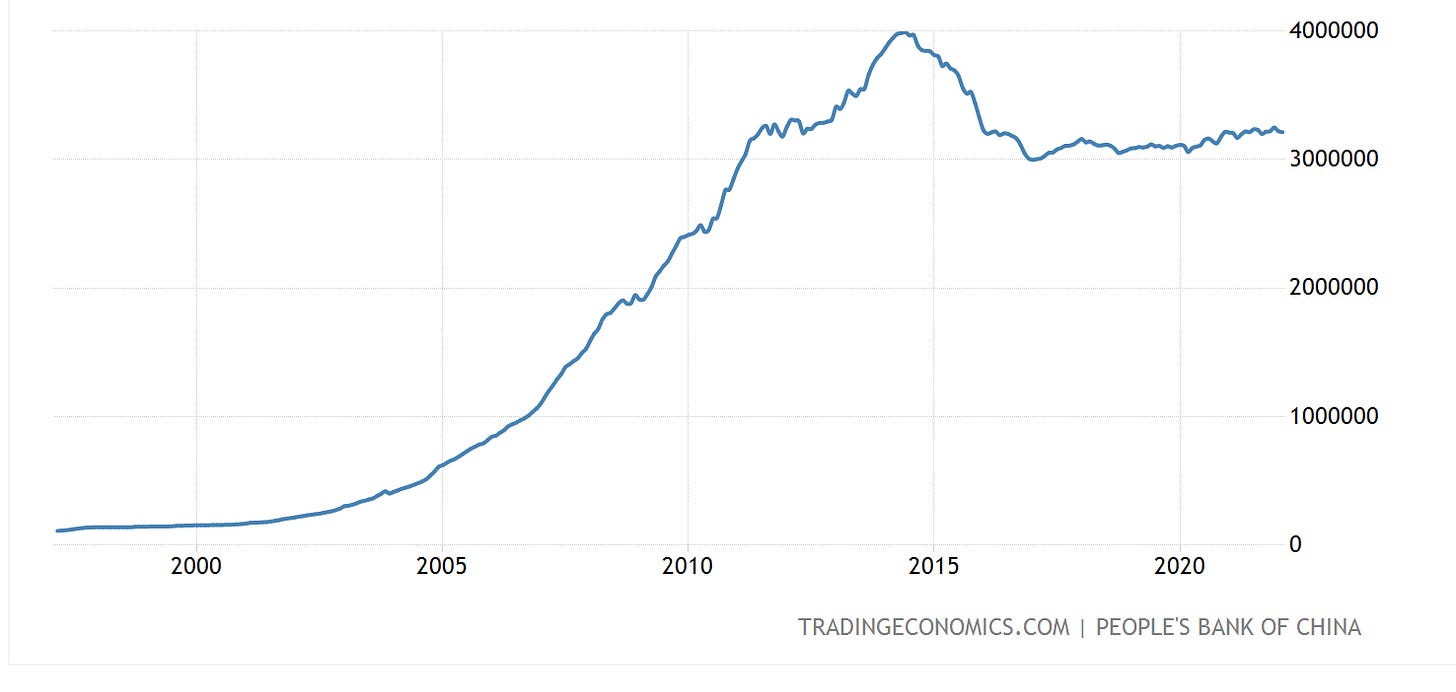

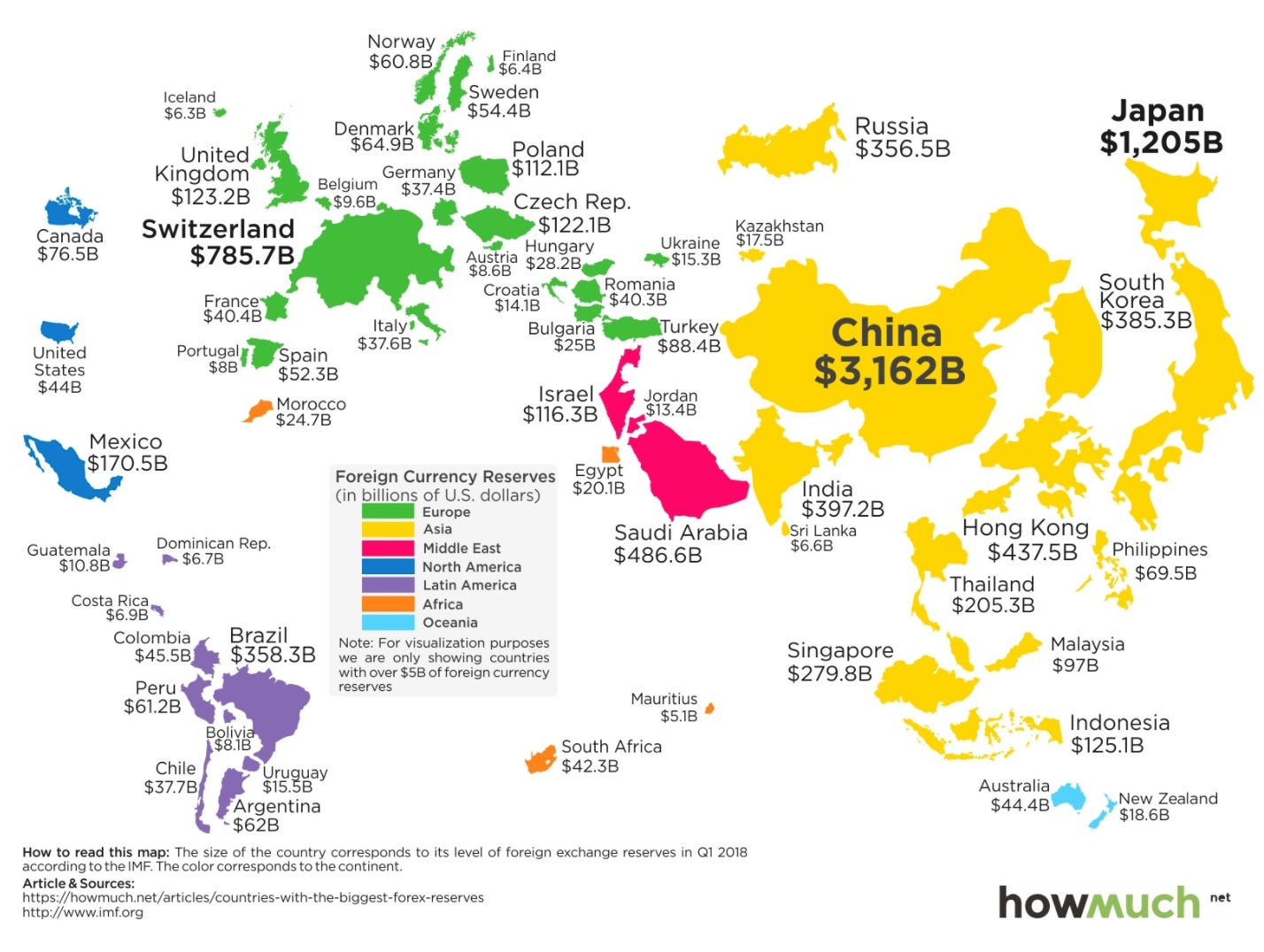

Nor does China, despite the mounting geopolitical tension with the US, show any immediate signs of breaking out of the world economy. Its recovery from COVID was assisted by a booming trade surplus. Reserves are well above $ 3 trillion dollars and the official figures likely understate the scale of its accumulation in recent years. China wants to avoid accusations of currency manipulation and does so by running its exchange interventions through the balance sheet of the state banking system.

Whatever the precise figure, China’s fx reserves clearly add up to a gigantic sum. By far the largest in the world. Notionally this gives China vast heft. But as Russia’s experience has shown, those reserves are, in case of conflict, vulnerable to sanctions. And if China wants to keep its reserves out of harms way, where is it to put them? Russia diversified out of dollars and into Euro and that too turned out to be a trap.

Riffing on Eswar Prasad’s concept of the dollar trap one might say that what Russia and China find themselves in, is a euro-dollar trap.

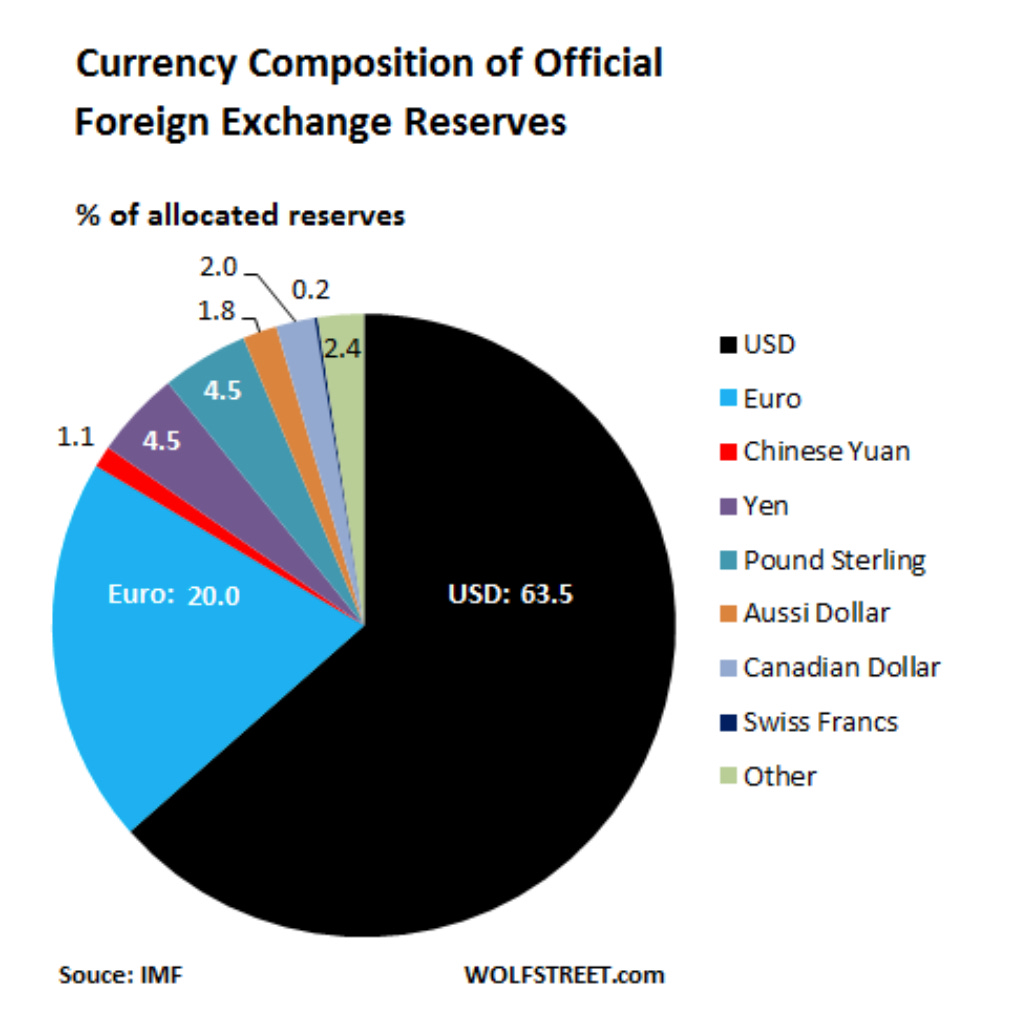

China’s antagonisms with Europe are far less acute than those of Russia. But so long as Europe and the United States hang together they have a hugely dominant position in investible safe assets. All told more than 80 percent of global reserves are held in either dollars or euros.

And even if one imagines that China found some place to park its trillions, that would hardly be the end of the world as we know it. The other major reserve holders in the global economy are all squarely Western-aligned. That would change of course if more and more trade shifted to renminbi, but it would gradual and a matter of degree, rather than a radical break.

Source: Visual Capitalist

If there is a route to large-scale internationalization of the renminbi it surely does not lie in building an exclusive currency block and confrontation with the West, but rather the reverse. It depends on it becoming increasingly interchangeable with dollars. As Foroohar remarks:

The Chinese want to de-dollarise, but they also want complete control of their own financial system. That’s a difficult circle to square. One of the reasons that the dollar is the world’s reserve currency is that, in contrast, the US markets are so open and liquid.

So far, there is very little appetite on the part of any major Chinese players to enter into a rogue partnership with Russia.

A Chinese banking exec in Beijing told me it’s “totally unrealistic” to expect China to help Russia evade financial sanctions simply bc its commercial ties with US/Europe are way bigger. “If China does this, the RMB internationalization will also only go backwards dramatically.” https://t.co/xC1fOBJWTW

— Lingling Wei 魏玲灵 (@Lingling_Wei) March 7, 2022

Rather than the path of confrontation and alignment with Russia, China will surely prefer to take the high-road of financial competition, seeking to offer global investors an attractive and liquid investment rather than a rogue alternative. In the arena of sovereign bonds, Chinese government debt viewed solely on the basis of total returns, is already a highly attractive proposition.

Since Jan 2020 China’s bonds have offered specularly better returns than other sovereign debt. @Gavekal via @SoberLookhttps://t.co/AOsyqU5twe pic.twitter.com/ZKxfVtzqA4

— Adam Tooze (@adam_tooze) March 4, 2022

So where does this leave us?

So far at least there are at least three tendency that seem visible.

What we are seeing is the formation of polarities rather than blocks. There are clear geopolitical antagonisms, but on the main axis, in Asia, this does not add up to consolidated blocs. The striking thing so far about the ripple effect from Russia is that though a new Cold War front may emerge in Europe, it is unlikely that will translate to East Asia.

Secondly there is a profound divergence between national security and economic concerns, glaringly demonstrated by the continuing Western reliance on Russian oil and gas, even as we airlift anti-tank weapons into Ukraine for the purpose of destroying Russian tanks and thwarting Putin’s ambition.

Finally, there is a prevalent sense of impasse. Neither China nor the US really has a trump card against the other. Both are stymied by a combination of internal and external factors. Putin’s imbroglio has not really released any tension, rather the opposite.

The contradictions are knotted tighter than ever.

****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of readers around the world. But, what sustains the effort, are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters that keep it going, press this button and pick one of the three options: