When I was asked to review Christopher Leonard’s The Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the American Economy I was not enthusiastic.

I don’t like Leonard’s folksy populist framing. As I explain in the resulting NYTreview, this goes deep.

But I did the review because I thought that from Leonard’s research I would learn more about the inner workings of the Fed and I was not wrong.

Leonard offers an off-center take on the Fed’s history from the perspective of Iowa-born, Kansas City central banker Tom Hoenig. The counterpoints between Hoenig and Volcker, Hoenig and Greenspan, Hoenig and Bernanke, Hoenig and Yellen and most decisively of all, Hoenig and Powell, structure the account.

For a recent interview with Hoenig, listen in here.

On Leonard’s reading, though Leonard never says so, Hoenig comes across as a Midwestern Austrian economist – concerned with the credit cycle and the allocative effects of booms and busts.

Leonard’s own account of the Fed’s policy in the 20th century, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, owes much to Allan Meltzer’s monetarist The History of the Federal Reserve.

Leonard’s book starts with Hoenig’s famous series of dissents in 2010 against Bernanke’s efforts to push a second round of QE. For conservatives this was an important stand against the slide into monetary abnormality. It was also, of course, a pivotal moment in the Obama Presidency and the loss of control of Congress by the Dems. As Paul Krugman put it so well, “It all went wrong in 2010”.

For Leonard, however, Hoenig represents the path not taken, the path that might have led away from the Wall Street excess of the following decades and the further escalation of wealth inequality.

It is, to my mind, an implausible counterfactual. But it does make for an interesting alt-history read.

Leonard’s jaundiced take on the super-wonk Fed chair’s – Bernanke and Yellen – is particularly striking. They appear as manipulative, irresponsible and ultimately, in Bernanke’s case, self-aggrandizing and self-righteous operators of an institution, that is both remote and alienating even to those who rise to the top of its internal hierarchy.

Leonard’s portrait is overdrawn, but it serves nevertheless as a useful corrective, to more familiar accounts.

No less telling is the contrast Leonard sketches between Hoenig’s grounded conservatism and Jerome Powell’s quicksilver trajectory from a gilded youth in Georgetown, to a lucrative perch in private finance and, from there, back to Washington and to the Fed.

But most interesting of all is Leonard’s account of Hoenig’s career through the financial crises that rocked the regional economies of the United States in the 1980s.

As a junior economist at the Kansas City Fed in the 1970s Hoenig got to watch first-hand how a credit and collateral spiral could operate in a pro-cyclical fashion. As Leonard describes it:

the (1970s) Fed wasn’t just inflating consumer prices. It was inflating asset prices as well. This was the form of inflation that was alarming to bank examiners like Hoenig. The value of farmland, a key asset for banks within the Kansas City Fed district, was rising steeply. So was the value of commercial real estate, and the value of oil wells and drilling rigs. These assets were the collateral on banks’ balance sheets, and their rising value encouraged more aggressive lending. Banks throughout the Midwest extended big loans to farmers, based on the theory that the value of farmland would keep rising and support the value of the loan. The same thing happened in the oil business, and real estate. Hoenig heard about short-term construction loans that were extended based on the theory that property values would rise so quickly that the loan could be refinanced as soon as the building was finished. This was pushing the banks to make riskier loans.

…. In 1981, Hoenig was promoted to vice president of the Kansas City Fed’s supervision department, overseeing a team of about fifty bank examiners. He got the job just in time to learn his most important lesson about the role of the Fed in American economics. He got to see what happens when a long period of inflation comes to a sudden, unexpected stop.

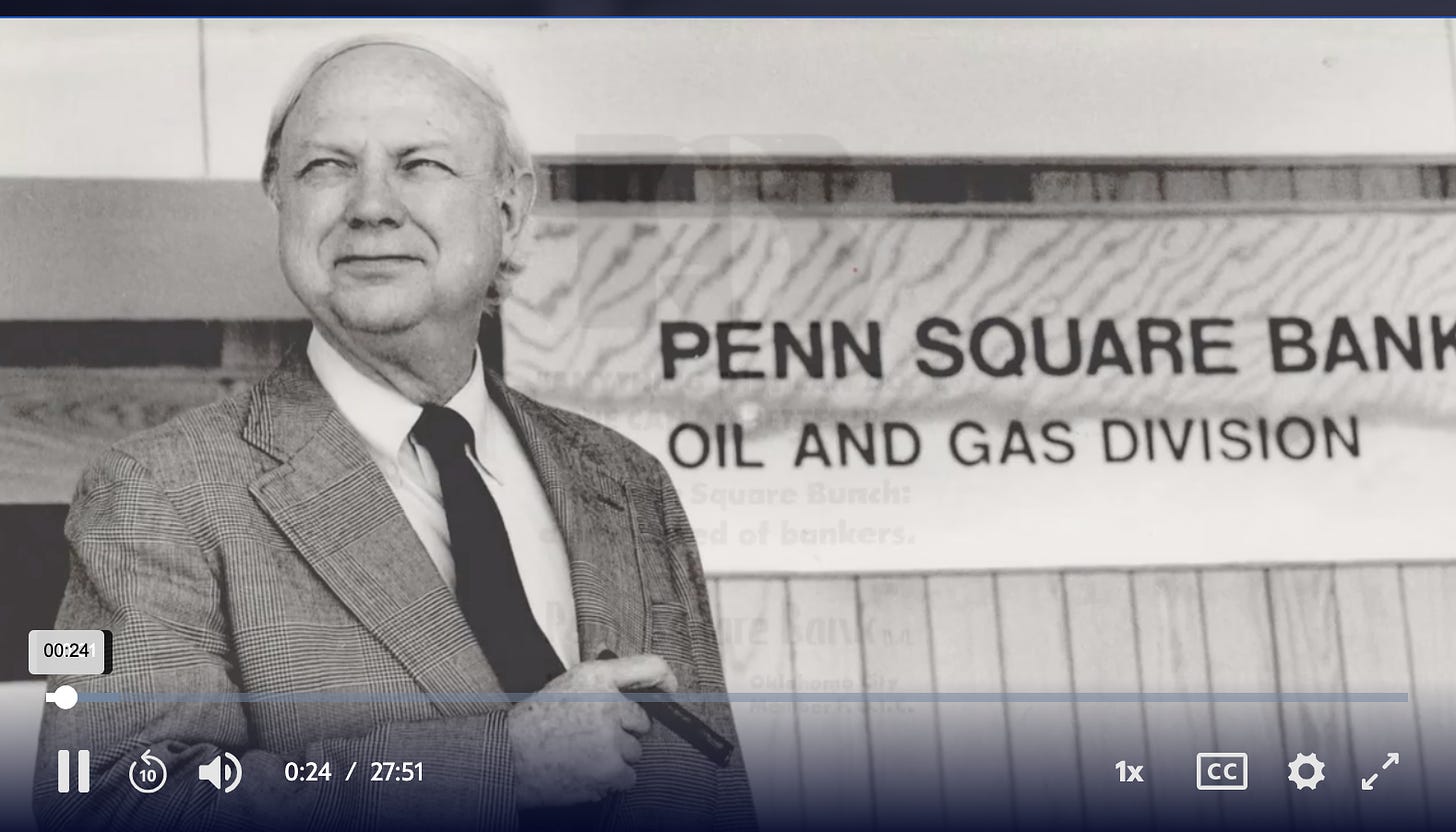

In 1982 more than a hundred American banks failed and Hoenig was at the heart of the action when overextended Oklahoma oil-lender Penn Square had to be wound down.

The Penn Square episode is truly fascinating. For background there is this great PBS episode.

The documentary highlights the extraordinary excess unleashed by the 1970s and early 1980s oil boom.

“His and hers” matching Lear jets parked on the runway at the height of the Oklahoma oil boom.

Amongst the larger banks that had snapped up Penn Square’s pipeline of high-yielding, high-risk energy loans was Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Co., of Chicago, which in the late 1970s acquired a total of $1 billion worth of energy loans.

In 1984 the failure of Continental Illinois and the ensuing bail out, first by a JP Morgan led syndicate and then by Fed and the FDIC led a Republican congressman from Connecticut named Stewart McKinney to declare to a Congressional committee: “Mr. Chairman, let us not bandy words. We have a new kind of bank. It is called too big to fail.”

But not all were. All told between 1980 and 1994 more than 1600 banks were wound up across the US.

It was this experience, Leonard argues, that Hoenig took with him to the Fed in Washington DC and it was the conservative lessons that it taught, which caused him to vote against further monetary stimulus in 2010. Delivering a further round of liquidity would feed an asset bubble and distort America’s economy and American society.

Unfortunately, Leonard never seriously weighs the alternative i.e. how much damage would have been done to the fragile recovery by a failure to provide stimulus. But that is another story …

As a decentering move, Leonard’s approach to the Fed from the periphery is really instructive.

The regional focus is also a reminder of the fact that the United States is shaped by the immigrant experience. If you do central banking in Kansas, you can find yourself despatched to places like Sedan, founded in 1871 after the German victory over France.

Hoenig’s Austrian-style economics may be tacit or home-brewed, but Hoenig comes from a German-American family and to his friends that carries with it certain character traits. “Tom’s German,” a friend told Leonard. “He’s strict. There’s rules.”

More pertinently, this heritage may actually have shaped Hoenig’s views on inflation risks. As Leonard tells the story:

After news got out that Hoenig was president (of the Kansas City Fed), one of his elderly neighbors approached him with a gift. It was a framed copy of a piece of German currency, a single bill with a face value of 500,000 marks. Below the bill was a simple inscription that read: “In 1921 this note would buy a large home. In 1923 this note would buy a loaf of bread.” It was a living memento of Germany’s era of hyperinflation. Hoenig hung it in his office downtown. It was a good reminder of the destructive power of inflation.

***

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of readers around the world. But, what sustains the effort, are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters that keep it going, press this button and pick one of the three options: