A modern, North American semi-truck is a substantial physical object. On average they stand 13.5 feet tall, 8.5 feet wide. With trailer attached, a truck is 72 feet long and weighs up to 80,000 pounds. It takes 400 to 600 hp to move at speed and 1000-2000 lb-ft of torque to pull it from a standing start. When the airbrakes are locked, it becomes an immense, immovable dead weight.

Such vehicles make an excellent object with which to form barricades and blockade space. If mobilized in coordinated groups, they can, as the protests in Canada have demonstrated, pose a serious challenge to the public control of public space.

This is kind of amazing: @OccTranspo is keeping an updated map of territory held by government and rebel forces in central Ottawa, on some blocks complete with descriptions of each parked truck https://t.co/TKSfvzS9z3 pic.twitter.com/5SVEbChFae

— Brian Platt (@btaplatt) February 8, 2022

Whereas the protests in Ottawa pose a political challenge to the government of Trudeau and his COVID policy, the blockade of the Ambassador bridge between Detroit and Windsor did substantial economic damage and is more reminiscent of classic labour protest.

In the age of coal, the power of the Triple Alliance – the coalition of miner workers, railway workers and dock workers – lay in their ability to comprehensively paralyze energy and logistical systems. Through the early 20th century coal supplied 80 percent of the energy needs of many industrial societies. Coal was hard to mine and hard to move. If you stopped coal. You stopped everything else. And thanks to the indispensable role of coal in electricity generation, that veto power continued to operate in many societies down to the 1980s.

The Triple Alliance was what made a general strike such an awesome prospect.

Trucks and truckers have never displayed that kind of comprehensive power to paralyze society. But they can cause considerable disruption.

In 1973 and 1979 American truckers engaged in widespread blockade, strike and picketing in protests at rising petrol prices.

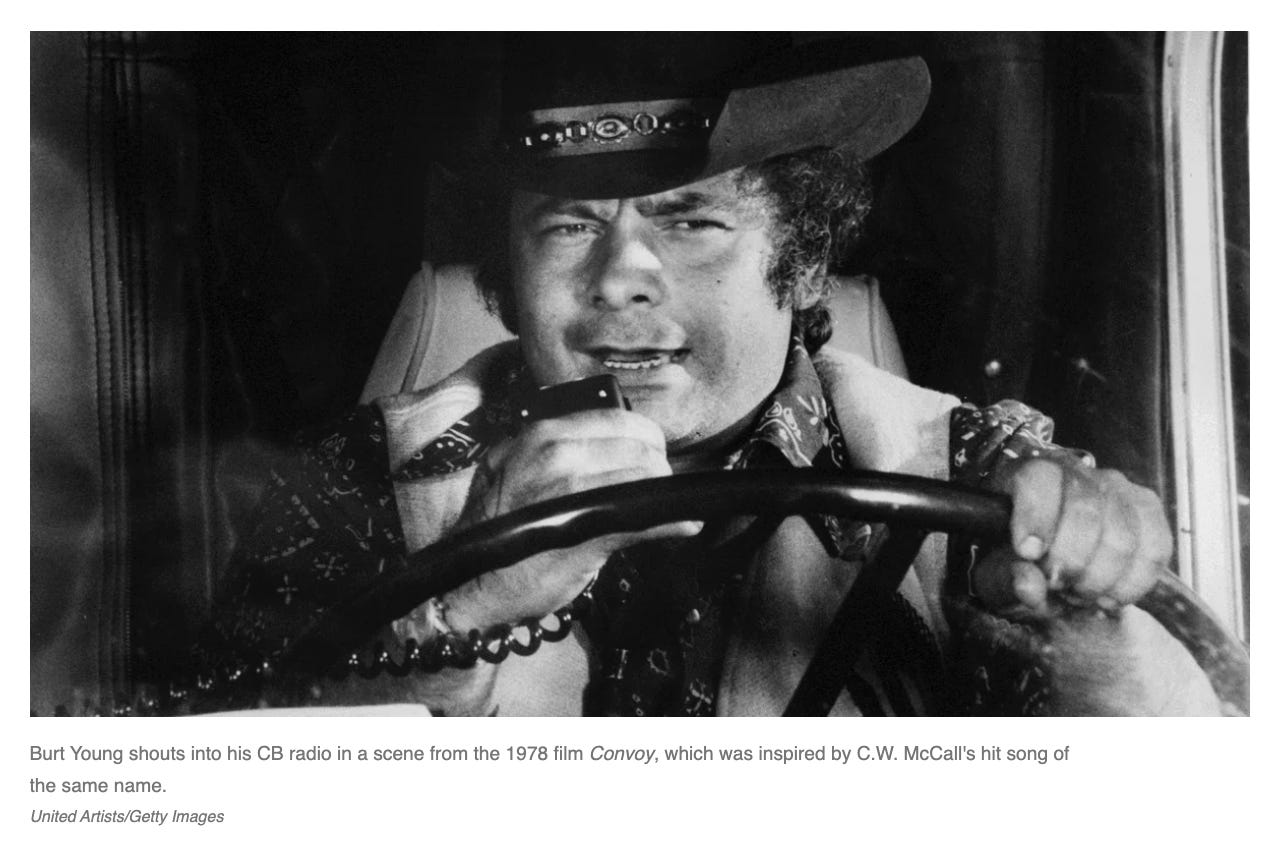

Those protests movements, which included not only blockades but sniping attacks on truckers who refused to stop driving, spawned a pop cultural craze for the mystique of the open road and the coded lingo of CB-radio talk. It even launched a pop hit.

That the 1976 song “Convoy” was created by a fictional musician is perhaps the least interesting thing about it. Attributed to singer-songwriter C.W. McCall — a character originally invented and performed by advertising executive Bill Fries for a bread company’s ad campaign — the song tells a tale of truck drivers protesting government regulations on a struggling industry. It features a conversation between them as they drive from California to New Jersey, spoken in the truckers’ inscrutable vernacular:

There’s armored cars and Interstate tanks and jeeps and rigs of every size.

Yeah, them chicken coops (weigh stations) was full of bears (police) and choppers filled the skies.

Well, we shot the line and we went for broke with a thousand screamin’ trucks

And 11 long-haired Friends of Jesus in a chartreuse microbus.

In 2022, right-wing TV host and commentator Tucker Carlson would like you to believe that what we are seeing in Canada is just such a broad based working-class rebellion.

Canada’s working class has finally rebelled after years of relentless abuse. Truck drivers are threatening to topple Justin Trudeau’s creepy little government with their big rigs, and they may succeed, actually. …. This is ‘the single most successful human rights protest in a generation’

This is a travesty of the actual situation.

Though some of the protesting truck drivers may be working-class, the protests have been disowned by the Canadian labour movement. As David Frum points out in the Atlantic:

The blockades are very much a rogue movement. They have been condemned by the Canadian Trucking Alliance and Canada’s Teamsters Union. About 90 percent of Canadian truck drivers are vaccinated; comparatively few of those protesting are professional truck drivers.

But though the resemblance to a conventional labour dispute may be superficial, the protests are revealing of the limits of public control of public space when not just human bodies, as in demonstrations, but substantial objects – machines, barricades, vehicles, coal shipments etc – are brought into play on the side of protestors.

As Cameron Abadi put it to me in the latest Ones and Tooze podcast, the question with which the Canadian authorities have apparently struggled, is simply how to clear the streets.

Will the police do the job? Does the Canadian state have the equipment necessary to do the job?

It seems that the Canadian military do have equipment like armored recovery vehicles which could be deployed to remove the trucks – 11 specialized tank recovery vehicles in total. But they are deployed in training grounds far from the action in Ottawa or the US-Canadian border.

Furthermore, elected governments hesitate before deploying the military against their own citizens, or even trucks owned by their citizens.

Asked whether this equipment would be brought in, Daniel Minden, a spokesperson for Defence Minister Anita Anand, cited Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who said Monday that the Emergencies Act “in no way brings in the military as a solution against Canadians. We are empowering law enforcement, and I think that’s what Canadians want to see.”

Law enforcement would normally rely on commercial towing operations to remove broken down trucks. But the commercial recovery firms are unwilling to be involved in clearing the streets of the capital.

“It would be business suicide,” one tow truck operator told the Globe and Mail“These are the trucking companies that call you for the work when they break down on the side of the road. You think … they’re ever going to call you again? You may as well just write your own ticket to shut your business down.”

Road side recovery for truckers, far from being a government-funded essential service, is a cutthroat private business, which, as the Globe and Mail reports

has also been under the spotlight for violence and corruption. A 2020 Globe and Mail investigation revealed that dozens of tow trucks were burned and at least four men with ties to the industry had been killed across the Greater Toronto Area, as companies competed for bigger slices of a lucrative segment of the industry known as collision towing or “accident chasing.”

Corruption investigations followed, leading to dozens of arrests, both of tow-truck drivers and also police officers across the province. The Ontario government has since pledged to licence and regulate the industry, but those efforts have been hampered by the pandemic.

“Our industry is struggling like many other industries,” Doug Nelson, executive director of the Ontario Recovery Group and the Canadian Towing Association, said. He is concerned about security risks with confronting protesters.

So, at the critical moment, lawlessness and Darwinian commercial competition trump the imperatives of the state. As far as unblocking the capital city is concerned, Nelson’s line was simple:

“This is not our fight.”

In the end it turns out that the tie breaker is not national state power, or the military but the municipal “police” resources of the City of Ottawa whose local public transit commission, OC Transpo, owns recovery trucks.

The capacity to recover broken down buses turns out to be the reserve power that may ultimately enable the freeing of Canada’s capital city.

***

The Ottawa protests are embarrassing for the Trudeau government, but it is the bridge protests in Windsor, blockading the main traffic artery to Detroit that pose the real economic threat.

Canada outranks both Mexico and China as America’s largest trading partner. In 2021, a total of $664 billion worth of goods moved between the two countries. The state of Michigan estimates that 30% of the total moved over the Ambassador Bridge linking Detroit and Windsor, Ontario. On a normal day, the one and half mile long bridge carries 10,000 trucks. They form a vital artery in the complex supply chains that link US and Canadian motor vehicle production.

The blockade on the bridge was much less substantial than that in Ottawa, but the bridge is another demonstration of the ambiguous relations between public and private power in the control of space.

The remarkable fact is, that the Ambassador bridge – the single most important international artery of the US economy – is a privately-owned monopoly.

Given the obvious need for a connection between Detroit and Canada, the idea for an infrastructure connection goes back to the 1860s. Public authorities conceive of both a tunnel and then a bridge. But it was Detroit auto interests with Henry Ford in the lead that actually finished the construction in 1929. For Ford it was further confirmation of his conviction that: “The only way things can be done today, is by private business.” The engineering firm that built the bridge was McClintic-Marshall Company of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the same firm that build the Golden Gate Bridge.

As this excellent University of Windsor case study by Kent Walker spells out, control of the bridge was subsequently contested by some of the more colorful billionaires of the American mid West:

In the 1970s, Warren Buffett and his partner, Charlie Munger, began buying shares. By 1977 Buffett had acquired his 25% stake in the bridge for $20 a share. Manuel Moroun, 40 at the time and “a little brash” by his own account, amassed his own 25% stake by the end of 1978 and paid Buffett $24 a share, later buying the rest. Moroun claimed title to the bridge on July 31, 1979.

You might think that one, privately-owned bridge, was not enough to connect America at a crucial point to its most important trading partner. Since the early 2000s plans have been debated to either build a new bridge, or add a new span to the Ambassador bridge.

The Detroit Three automakers (General Motors (GM,) Ford and Chrysler) are among the most vocal supporters of the (new) DRIC Bridge. The CEOs of Ford, GM and Chrysler have all stated that a new bridge is essential.

But, unsurprisingly, the business interests who own the Ambassador bridge, led by the doughty Manuel Moroun, have every interest in maintaining their monopoly and used every legal means to stop work on an alternative.

Moroun’s defense of his monopoly included law suits against the US and Canadian governments and an astroturf campaign against evictions required to build a new bridge. In July 2011, the Canadian Transit Company, the Canadian-side of Moroun ownership of the Ambassador Bridge,[63] ran an ad campaign against “$2.2 billion road to nowhere”. In 2012 Moroun’s interests spent $30 million on a proposed amendment to the Michigan Constitution that would have required approval of both the voters of Detroit and the voters of Michigan in statewide elections to build the bridge. Moroun lost by a vote of 60 to 40 opening the path for a public bridge alternative.

Ground was finally broken on a new bridge in 2018. It is due to be completed in 2024.

****

The Canadian trucker protests are not a working-class rebellion. But they do expose the limits of the idea of the public control of public space. Both at the grand scale of international infrastructure and the use of public roads, public power is mediated and negotiated with private interests.

The manifestation of “the state”, or the “state effect” cannot simply be taken for granted. It depends on the mobilization of resources both large – billions of dollars in funding for a new bridge – and small – the availability of a fleet of tow trucks that can actually be commanded by the public authorities.

It also depends on building political coalitions to support the exercise of sovereign power – through referenda or the mobilization of the auto-industry – and to check the subverting influence of private monopolies, the right-wing populist media etc.

It is not a state of affairs, but a continuous flux.

****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But, what sustains the effort, are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters that keep it going, press this button and pick one of the three options: