Viewing the 21st century from 2001.

This week is the 20th anniversary of the coining of the concept of BRICs by then-chief economist of Goldman Sachs, Jim O’Neill.

When O’Neill was named chief economist of Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in 2001 he had a point to prove. He was a known as a man of the currency and bond markets. Could he be a “thought-leader” adding intellectual gloss to Goldman’s brand?

O’Neill had written his PhD in the 1980s on the recycling of oil surpluses. The 1990s had seen a surge of growth across what were then still low-income countries. The tensions of the Cold War were unwinding. America was shaken by the 9/11 attacks. The question that O’Neill and the Goldman Sachs team set out to explore was, how would the world of the 21st-century be shaped by forces beyond the West.

Since the 1990s there had been talk of a rising Asian middle-class. That optimism had suffered something of a setback with the crises of the late 1990s, but by 2000 growth across Asia had resumed. In 2001 and 2002, Goldman was predicting that real GDP growth in large emerging market economies would handsomely exceed that of the G7. What, the Goldman Sachs team asked, would the world look like, if that lopsided pattern of growth was extended into the future. The result was Goldman’s Global Economic Paper Number 66: “Building Better Global Economic BRICs,” published on Nov. 30, 2001.

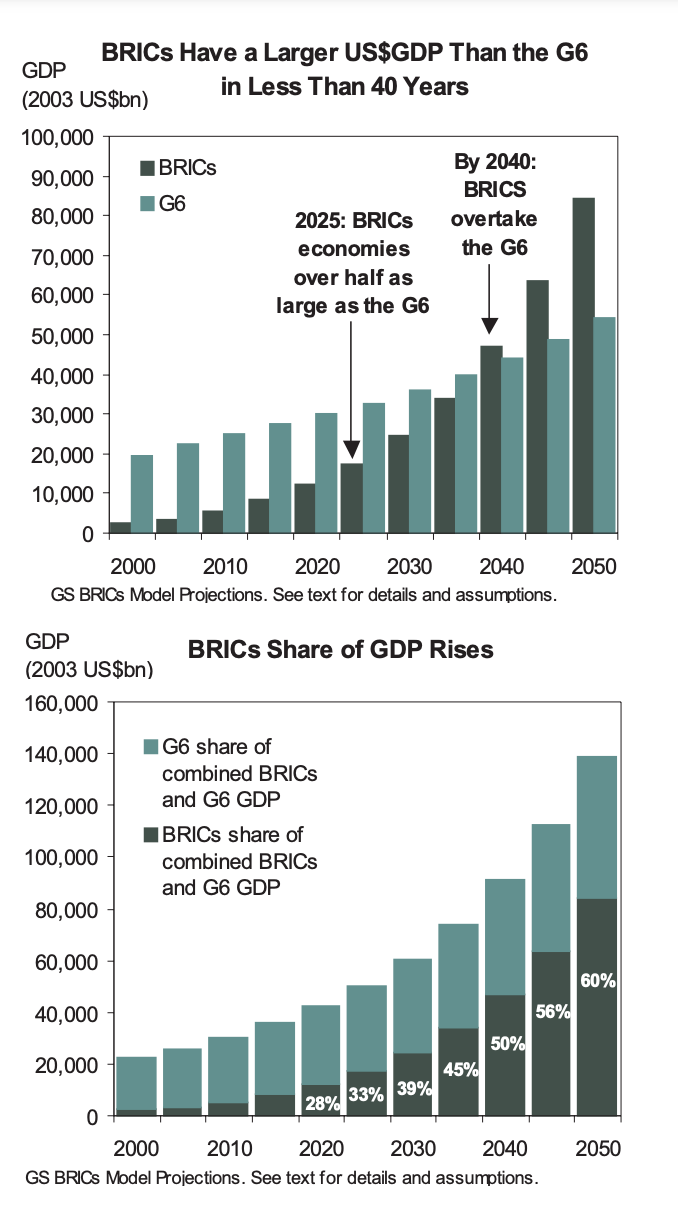

The impact of the 2001 analysis was amplified by a second BRICs paper published in October 2003 in the Goldman series by Dominic Wilson and Roopa Purushothaman. As O’Neill told Bloomberg reporters, “it was after the 2003 paper that O’Neill remembers financial titans such as Blackstone Inc. Co-Founder Stephen Schwarzman began calling Hank Paulson, then Goldman’s chief executive officer, to rave about the vision. One chart from the latest paper was downloaded from Goldman’s website ten times more often than any other document …”

Source: Goldman 2003

Reading the 2001 paper and its follow-up, Goldman’s 2003 paper on BRICs, one is first of all reminded of how novel the idea was that the world would be shaped over the coming decades not by Europe and America, but by growth in Asia and the emerging markets. Again and again the Goldman Sachs researchers ask their readers to suspend disbelief. They stress that they are simply projecting forward visible trends and extrapolating from uncontroversial structural facts.

A typical passage is this one from the 2001 paper:

We do not really know the ‘right’ answer as to which method is right but will now go on to argue that looking at relative real GDP and inflation trends for the purposes of future global economic policy implementation, it may not matter. Whether you look at the future either in current US$ or PPP terms, relative positions of key countries in the world economy are changing. We will now try to show that China especially deserves to be in the ‘G7 Club’, and under some scenarios, so do others-certainly Brazil, Russia and India relative to Canada.

A repeat of the 2001/2002 outlook is highly unlikely over the next 10 years, but if China and the other three BRIC countries succeed in achieving fast growth and low inflation, then the relative GDP sizes may indeed be more like today’s PPP-determined numbers

It is also striking that the original purpose of the O’Neill analysis was not to promote the EM as investment destinations. As he explained to the IMF, the BRICs concept was advanced to make the case for a change in global economic governance. The G7 had emerged after the collapse of Bretton Woods in the 1970s as a forum for global coordination between Europe, Japan, and North America. But it was increasingly unrepresentative of the dynamic of global growth. As a legacy of the 1970s, Europe and Canada were massively overweight. The formation of the Eurozone created a solid European block and would offer the opportunity to shrink the G7 back to G5.

Even on a current GDP basis, the Chinese economy is slightly bigger than Italy, so an expansionary monetary or fiscal policy in China would be likely to have slightly more global impact than similar policies in Italy. This may be particularly relevant if an economic ‘shock’ such as the 1997/98 Asian Crisis affects the neighbouring region more than elsewhere. Obviously if PPP weights are more representative than current GDP, China’s economy is about four times bigger than Italy’s, magnifying the relative impact of policy change. If the G7 was to become a forum where true worldwide economic policy co-ordination was discussed, the US, Japan, Germany, France and the UK would be joined by China and India rather than Italy and Canada if PPP weights were the appropriate judge

It was not just the fact that China’s economy by 2001 was already far larger than that of Italy, the crucial point for O’Neill was that shocks to the global economy had since the 1990s not issued from the existing membership of the G7, but from outside. If the world economy was going to have collective leadership, it was crucial to include the BRICs as the main growth nodes and as big economies close to where the instability was likely to come from.

The expansion of the G7 did not happen. But in the wake of the Asian financial crises, the G20 had been formed as a meeting of finance ministers precisely to achieve the effect of more expansive coordination. It would be promoted by the 2008 financial crisis as the preeminent forum for the leaders of the large economies.

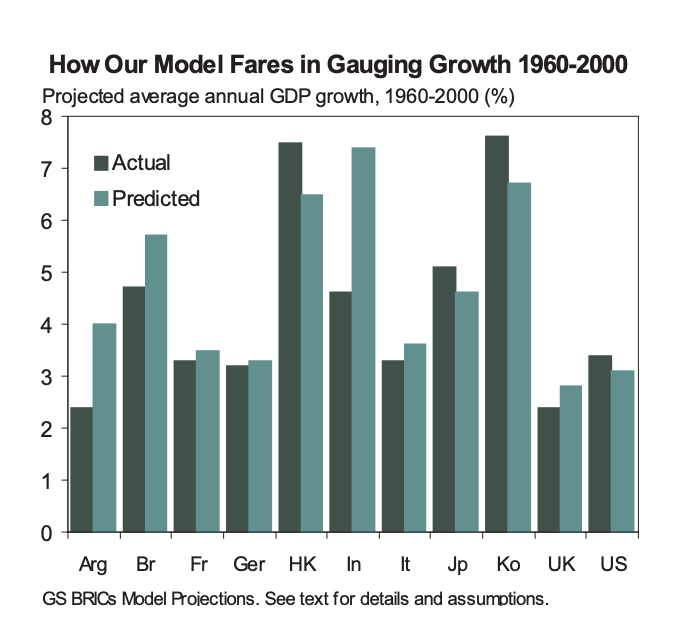

The Goldman forecasts for global growth in the early 2000s were not overly optimistic. They were conditional. In an interesting backcasting exercise they recognized the fact that Latin America had disappointed in previous decades. Clearly those problems might return.

Source: Goldman 2003

In the original formulation by Goldman Sachs, BRICs, referred only to Brazil, Russia, India and China. The “s” was a plural.

The absence of an African economy was on the mind of the Goldman Sachs analysts. The 2003 report includes a box on the possibility of adding South Africa to the list. Goldman did not think it inconceivable that its growth might hit 5 percent annum.

The first summit meeting of BRICs leaders took place in September 2008 on the side lines of the UN General Assembly meeting. Russia hosted a formal meeting in Yekaterinburg in June 2009.

In December 2010, the BRICs became the BRICS when South Africa was invited to join what was now a newly minted political grouping.

Source: World Finance

Writing in the FT on the occasion of the anniversary, O’Neill’s retrospective on the concept focused on the question of whether they had got the future right. The upshot is that as far as China and India are concerned they were not far off. In fact, as far as China was concerned, they were, if anything, too cautious.

As far as the BRICs as a group were concerned they were right about the first decade. Between 2000 and 2011 the BRICs more than doubled their share of the global economy from 8% in 2000 to 19% in 2011. But since 2014 Brazil and Russia have gone through prolonged recessions, due to domestic political turmoil, international sanctions and the commodity price recession.

By August 2013, amidst the “taper tantrum” Brazil and India found themselves included in a new and less promising grouping – the Fragile Five – an idea coined by Morgan Stanley, to capture the economies vulnerable to investor outflows (joined by Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey).

As an investment strategy betting on the BRICS has not been a winning move. As Bloomberg commented.

Franklin Templeton Investments and Schroder Investment Management launched BRIC-themed funds TEMBRAC and SCHBREA in October 2005, with HSBC Holdings Plc and Goldman Sachs following soon after with their own HSBBRIC and GBRAX. By 2007, Invesco Ltd. and BlackRock Inc. had launched exchange-traded funds built around those developing nations as well with EEB and BKF.

None of those investment vehicles quite lived up to the hype of the early years, though. Goldman folded its money-losing BRIC fund in 2015, merging it with a broader emerging-market portfolio. Invesco’s ETF was shuttered last year in a wave of closures.

An investment into Templeton’s BRIC fund upon its inception would net a total return of roughly 130% today in dollar terms, compared with 220% and 440% for portfolios that tracked the emerging-market benchmark and the S&P 500 Index respectively, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Ziad Daoud, chief emerging markets economist at Bloomberg Economics has recently coined a new concept – “BEASTS”—Brazil, Egypt, Argentina, South Africa and Turkey— “which he sees as most vulnerable due to the combination of lower reserves, weaker current account balances and higher external debt”.

Looking back as a historian what is most striking is not so much the accuracy of the predictions, but the shock of the new registered by the emergence and then the circulation of the BRICs concept. Something radical was happening. Coining a neologism was a way to respond to the dramatic change in the structure of the world economy.

Many of us had to go through that reorientation.

Personally, I was shocked into the realization of the global by work I was doing in the late 1990s with the senior leadership of BP, the oil major (h/t Melissa Lane). The close encounter with the wide horizons of the oil business rocked my world. BP was my globalization shock.

Working on a home computer, I embarked on an amateur effort to map cross-national global inequality, marrying national inequality numbers to PPP-adjusted GDP numbers to make a rough estimate of the global middle class. I presented the results, which I will have to excavate from the files in my office, to a BP audience sometime over the winter of 2000-2001. I remember my colleague Simon Szreter button-holing me after my presentation to tell me that there were people working along similar lines at the World Bank.

There was a phase, between finishing Statistics and the German State and before I settled on writing Wages of Destruction, in which I envisioned writing a book about the rise of the Asian middle class.

It was clear that the 21st-century was going to be different. We’ve been scrambling to catch up all along.