A guide to the agenda of Germany’s new government.

Mehr Fortschritt Wagen

Olaf Scholz has completed his remarkable comeback. After relatively concerted and efficient negotiations, the traffic-light coalition is complete. It is an unprecedented agreement between the Social Democrats, the Greens, for whom this is the second chance at national government, and the FDP, who turned down the chance to govern in 2017 and will now fly the flag for their version of free market liberalism.

The cabinet positions are distributed as follows:

SPD – Chancellor, Interior, Labour and Social Policy, Defense, Housing, Health, International development. Chancellery. Migration and refugees and integration. New (Eastern) member states.

Greens – Foreign Office, Economy and climate, Family, Pensions, Women and Youth, Environment and nuclear safety, Food and agriculture. Plus the right to nominate Germany’s EU commissioner provided the EU President isn’t German. Culture and Media.

FDP – Finance (outch), Justice, Transport and digital, Education and research.

The coalition has issued its founding document, the Koalitionsvertrag (coalition contract) – under the title “dare more progress” – a nod to Willy Brandt’s famous manifesto – “dare more democracy”. It promises an alliance for freedom, justice and sustainability.

As if the shift from democracy to progress was not telling enough, the coalition partners then add: “Progress must go hand in hand with a promise of security and the confidence that this can be achieved together.”

The rationalization for the government of three very different parties seeks to make a virtue of their differences.

Their different outlooks reflect the complexity of German social reality they insist. “If we manage to push things forward together that can be an encouraging signal for society as a whole: that cohesion and progress is possible even with very different points of view.” 129-131

It is a document written by committee. There are long passages of boilerplate. It is very long – 177 pages. But the sophistication of its language and terminology is also testament to the sophistication of German public discourse.

This is a first, rapid reading of the document. I have cited line numbers where relevant. All told it comes to 6018 lines.

Was das Land herausfordert – what challenges the country

Germany, as the authors of the manifesto admit, faces a polycrisis. This consists of “pandemic, climate crisis, competitiveness, international system competition, digitization, societal tensions (gesellschaftliche Spannungen)” 31-35

“These challenges are immense, interwoven and demanding in their simultaneity.” 32 “They will shape our country and society for the future. If we manage these transitions, they offer great opportunities. The task of the coalition is to set the necessary innovations in motion politically and to provide orientation. We thus want to unleash a dynamic that acts into the entire society.”

Modernising The State

Strikingly, the coalition agreement begins with more than a dozen pages dealing with the need to modernize the state itself. 39 This is a constant refrain of modern German politics, but one dramatically amplified by the weaknesses exposed by the COVID crisis.

“Germany will only be able to meet the challenges of the moment (auf der Höhe der Zeit agieren), if the state itself is modernized.”

One passage reads: “We will create a set of rules that open the road to innovation and measures that will allow Germany to embark on a path of 1.5 degrees change.”

The coalitions promises as “fundamental change’ to a “facilitating, learning and digital state”, that acts presciently for its citizens. Its aim should be to make life easier and to foster the “energy of civil society”.

National identity

Some of the most strikingly clear and emphatic passages of the manifesto concern migration and national identity.

“We are united by an understanding of Germany as a diverse society of immigration.”

In the 1970s-1990s, when the current generation of German leaders were growing up, any such statement would have been politically explosive.

They continue: “Migration has been and is today a part of the history of our country. Immigrants, their children and grand-children have helped to build our country and shape it. The 60th anniversary of the guest-worker treaty with treaty with Turkey is symbolic of that.” 3943-5

Like the last Red-Green government, this one promises to modernize Germany’s citizenship laws. This time it will permit multiple citizenship. Naturalization will normally occur after 5 years, or 3 years in the case of exceptional integration performances (sic) (Integrationsleistungen). Right of abode will be acquired after 3 years. Retroactively they promise to examine the naturalization of the Gastarbeiter generation who were for a long time excluded form citizenship.

Any mention of the concept of ‘race’ will be expunged from the German constitution

Climate policy

Climate policy is everywhere in the manifesto. After the modernization of the state, it is the first substantive subject heading. But it is also a catch-all category for every measure of industrial policy and business promotion.

This may reflect the fact that Robert Habeck (Greens), who had set his sights on the Finance Ministry, a position for which I strongly backed him, has had to settle instead for the position of Minister of the Economy and Climate. Previously, under Peter Altmaier of the CDU, this was the Ministry for the Economy and Energy.

Here is the rubric for Habeck’s Ministry:

This line is laid our clearly also in the phrase: “We see the path to a CO2 neutral world as a great chance for Germany as a industrial economy (Industriestandort Deutschland).”

To put flesh on these bones, the manifesto does contain a number of important commitments.

Renewables to make up 80 per cent of electricity output by 2030 (previous target had been 65 per cent)

Use two percent of German land for onshore wind power; begin work on comprehensive planning of these areas in first half of 2022 with federal, national, local authorities

Communities near renewables installations should “profit appropriately”

Where wind farms are already in place, it must be possible to replace old wind turbines with new ones without a major approval procedure

Offshore wind targets: 2030: 30 gigawatt; 2035: 40 GW; 2045: 70 GW (status 2020: 7.8 GW)

Solar PV target for 2030: ca. 200 GW (status 2020: 54 GW)

Rooftop solar mandatory for new commercial buildings, “as a rule” on new private buildings

Phaseout of coal to happen ‘ideally’ by 2030 (previous target had been 2038). This is to be supported by rapid development of renewables AND construction of high-efficiency gas power stations (a phrase repeated two times in the manifesto). Gas-fired stations must be ready for conversion to green gas, H2. This is likely to cause consternation in the climate community. More gas capacity may well be a step in the wrong direction.

Goal of at least 15m electric cars on German roads by 2030 (out of a total stock of 48 million).

Government to ensure that industry is offered competitive electricity prices to encourage rapid electrification.

Heavy emphasis on investment in green hydrogen with aim being to establish a European Union for green hydrogen. In interest of developing the market as rapidly as possible, subsidy will be provided for hydrogen use even in cases where supply of green hydrogen fuel is not yet secured. Seen as vital for areas where eletrification if not feasible.

Public procurement to favor low-carbon industries.

Establish minimum CO2 price of €60/tonne

Commitment to EU program of expanding carbon pricing under EU’s “Fit for 55” program.

Europewide minimum carbon price with carbon border adjustment, expanding into an open international climate club.

Carbon Contracts for Difference (Klimaverträge, CCfD)

Regular and serious stress testing of heating and power supply systems.

We want to mobilize more capital for energy transformation. With this in mind the coalition commits itself to exploring how public development banks may be able to provide risk guarantees for energy investment. In dialogue with business, trade unions and trade associations the coalition will engage in negotiations to found an “Alliance for Transformation”, which in the first six months of 2022 will provide stable and reliable parameters for the ongoing energy transformation.

Germany’s KfW public investment bank will set up a transformation fund. They will mobilize contracts for difference, lighthouse “first mover” projects and incentives for innovation in climate-neutral production.

The coalition recognizes that negative emissions are part of the climate strategy and undertakes to prepare a long-term strategy for dealing with 5 % residual emissions.

Research, innovation, investment

The coalition commits to raising public spending on research and development to 3.5 percent of GDP by 2025.

Key areas of research are: climate-neutral industrial processes (e.g. steel); clean energy and mobility; climate research, biodiversity, sustainability, earth systems; adaptation and sustainable agriculture; resilient health care systems that take advantage of possibilities of biotech and advanced medicine with an emphasis on addressing illnesses of old age and poverty; technological sovereignty with a focus on ditital, artificial intelligence and quantum technologies; data-based solutions across sectors; space and ocean exploration with a view to sustainable utilization; societal resilience, gender parity, social cohesion, democracy and peace.

Carbon pricing and just transition

In light of rising CO2 price component, the renewable energy transfer payment system that launched Germany’s energy revolution twenty years ago will be wound down. As of 1 January 2023 any subsidy costs will be transferred to the general budget. Finance will be provided by way of a special energy transformation fund, EKF, that is fed from the revenues of carbon emissions trading and general revenue.

With the completion of the exit from coal (in the 2030s) any further subsidy to renewable energy will cease.

The aim is to remove both subsidies and supplementary payments for energy, but the coalition also promises that business will face no increase in energy costs. Can this circle be squared?

The German government is committed to the EU’s aim of expanding CO2 pricing under Fit for 55 program to heating and transport. Steps must be provided to ensure that EU member states provide social compensation.

“We are committed to a rising CO2 price as an important instrument, in combination with a powerful social offset… what is good for the climate should be cheaper – what is bad should be more expensive.”

By the 2030 there should be a unitary European CO2 market for all sectors that does not transfer costs in an unfair way to consumers. The language is unclear but the presumption seems to be that the consumers in this case are households (not businesses).

The current ETS price is 60 Euro/Tonne. Prognoses suggest it will remain at least at this level until 2040. Were prices to slump and the EU not to agree on a minimum price, Germany will take national measures (through cancelling permits or a minimum price) to ensure that the price does not fall below 60 Euro/Tonne.

Energy and CO2 prices should be treated indifferently. The new government, in light of social concerns, will take account of the current global energy price surge and maintain its intended price trajectory for energy and CO2. To offset a future price increase and ensure social acceptance of the market mechanism, the new government will develop a social compensation mechanism.

Income/welfare – SPD

Olaf Scholz himself is known above all for his commitment on social issue.

The SPD’s key electoral agenda item was the increase in the minimum wage from €9.60 an hour to €12. Further help will be provided by cheaper energy for residential customers, thanks to the abolition of the renewables levy on electricity bills

The pension system will be kept stable: there will be no reduction in pensions and no increase in the pensionable age. The private pension system will be comprehensively reviewed.

‘Basic income’ for children to be introduced. Strong emphasis in the manifesto on equality of opportunity and the promotion of social mobility by way of early childhood education.

Another of Scholz’s personal agenda items is the fairness of taxation, both with regard to corporate taxes and tax avoidance.

Housing – SPD

Housing is one of the key agenda items of German domestic policy at the moment.

The new government commits to building 400,000 flats a year, 100,000 of them subsidised by the state.

It also commits to toughening rent controls, particularly in big cities with high demand; increases capped at 11 per cent over three years (previously 15 per cent).

A ministry of construction in the hands of the SPD will drive this popular agenda item.

On housing and climate, as Clean Energy Wire notes, the aim is to “Reach a fair division of the CO2 price (on heating) between landlords on the one hand and tenants on the other. On 1 June 2022, the coalition wants to introduce a new model that, based on a building’s energy class, regulates the allocation of the CO2 price according to the fuels emissions trade law (Brennstoffemissionshandelsgesetz – BEHG). Should this legislative solution not be possible in time, the increased costs due to the CO2 price will be divided equally between landlord and tenant from 1 June 2022.”

Europe

The manifesto makes very frequent reference to Europe, but on the absolutely cardinal issue of European finance it has relatively little to say. There are fewer lines on European financial policy than there are on combatting money laundering.

The passage reads as follows:

“Europe’s Stability and Growth Pact has proven its flexibility (a favorite Scholz phrase). On the foundation it provides we want to secure growth, maintain debt sustainability and ensure sustainable and climate-friendly investment. The further development (Weiterentwicklung) of the fiscal policy rules should be orientated towards these goals, to secure their effectiveness in the face of the challenges of our times.”

The acknowledgement that the rules will have to be developed and that they must take account of the “challenges of our times”, is potentially a significant concession on the part of the FDP. Its meaning, however, is unclear.

“The stability and growth pact should be simpler and more transparent, in part also to ensure its implementation.”

Everyone agrees on this, of course.

“Next Generation EU (NGEU)” package is described, in passing, as an instrument that is limited in time and size. That is not quite the same as saying that it is a one-off instrument not to be repeated. But could be interpreted in that direction.

“We would like to see reconstruction program achieving a rapid and future-orientated recovery from the crisis for all of Europe. That is also in the elementary interests of Germany (Das liegt auch im elementaren deutschen Interesse.)”

One can almost hear the SPD and Greens pounding the table on this issue. But what it means in practice is left unclear.

“We want to strengthen existing instruments for budgeting.”

En passant the coalition agreement remarks: “Price stability is elementary for the prosperity of Europa. We take very seriously the worry of people about rising inflation. The ECB can best fulfill its mandate, which is above all the goal of price stability, if budgetary policy fulfills its responsibilities both at the EU level and in the member states.”

Again, that could be construed in a profoundly conservative direction, or not. What, after all, are the responsibilities of budgetary policy?

And that is it. Over and out. No more. As Christian Odendahl comments, it is a statement of principles, at most, rather than a concrete policy.

The German coalition agreement is not conclusive about Germany‘s fiscal position, neither at home nor in Europe.

— Christian Odendahl (@COdendahl) November 24, 2021

It is relatively open, stating principles and options. Which is … probably a good thing.

Since an assertive German position on European policy is a matter of deep concern, Christian may be right: the less said the better.

One point that may turn out to be significant, concerns European policy coordination. The coalition parties specifically commit themselves to regular European-policy coordination meetings.

I don’t know whether this was in previous coalition agreements. It may be significant as a form of oversight over independent “Aktionen” by various Ministries. It would provide a way for the SPD and the Greens to check any tendency on the part of Christian Lindner, to use Finance Ministry as a bully pulpit for a more conservative line than is approved by the rest of the government.

It should be said that right now the financial issue in Europe is less pressing than the rule of law clash with Poland and on that theme, as several observers have noted, the agreement contains very strong language.

The German coalition agreement🚦 devotes an entire section to the #RuleOfLaw— with a strong, principled stance. The consistent & prompt use of EU tools is *exactly* what we have been calling for.

— Katalin Cseh (@katka_cseh) November 24, 2021

A really hopeful sign for all those in 🇭🇺 & 🇵🇱 fighting for democracy. https://t.co/x2j1IUt5bF

On Europe’s future as such the coalition program is downright radical.

“We will use the Conference for the Future of Europe for reforms. We support necessary changes to the Treaties. The Conference should open the way to a constitutional assembly leading to the development of a federal European state (föderalen europäischen Bundesstaat) that will be organized on the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality with a charta of basic rights as its foundation. We want to strength the European parliament … We will give priority to the community method, but, where necessary, go forward with individual member states. We support a unitary European franchise with partially transnational lists and a binding Spitzenkandidat-system.”

These passages are, in fact, taken straight out of the electoral program of the FDP.

There they declare:

“This path is an explicit alternative (Gegenmodell) to the retreat of Europe into nation state particularism (nationalstaatliche Kleinstaaterei), or the creation of a centralized European super-state. Until this is realized we want to see European integration deepened in parallel on the model of a “Europe of different speeds”.

It is hard to avoid the impression that this is the kind of boilerplate you insert when you know it has no possibility of being realized in practice. We shall see.

Public finances

If the coalition agreement is vague on European finance, it is not much more concrete when it comes to domestic policy.

Only in outline can one discern how the clash between the liberal FDP and the investment-focused Greens may be squared.

As of 2023, the debt brake will come back into force. But, the coalition agreement goes on to stress, that we will need to mobilize “resources on an unprecedented scale (in nie dagewesenem Umfang zusätzliche Mittel) to meet the goal of containing climate change at 1.5 degrees, transforming the economy and meeting after-effects of corona.”

To add emphasis, the agreement goes on to stress that meeting those challenges can only be achieved over the long-term if essential and urgent investment is undertaken. Significantly, the agreement explicitly emphasizes that delaying investment will dramatically increase future costs.

Is this the opening to a redefinition of financial sustainability in terms of the urgency of climate change? This may be suggested by the following passages. The coalition will establish, “security of planning by making long-term investment commitments that are laid out in a long-term investment plan. Embarking determinedly on the transformation is an essential precondition for the long-term sustainability of public finances.”

But then the agreement immediately adds: “At the same time the federal government must bundle all its resource and deploy them concertedly to ensure that as of 2023 the constitutionally anchored “normal path” according to the debt brake can be achieved.”

Quite gratuitously, in the midst of a domestic-policy section, the document remarks: “Germany as an anchor of stability must continue to live up to its leading role in Europe (Vorreiterrolle in Europa). “Financial solidity and frugal use of tax money are principles of our budgetary and financial policy.”

This passage is so striking that I repeat it here in the original: “Deutschland muss als Stabilitätsanker weiterhin seiner Vorreiterrolle in Europa gerecht werden. Finanzielle Solidität und der sparsame Umgang mit Steuergeld sind Grundsätze unserer Haushalts- und Finanzpolitik.”

What “leading role in Europe” does this government imagine for itself, one wonders.

What the Greens had promised is 50 billion euros per annum in public investment in Germany to meet the challenges of the climate crisis and to rebuild Germany’s public infrastructure.

Perhaps it is significant, therefore, that at this point the coalition document pivots to discussing the mobilization of private capital and the role of public development banks in mobilizing capital. They will offer capital-market-adjacent (kapitalmarktnah) risk guarantees. The KfW will be activated as an agent of innovation and investment. Future funds for start ups and touted as a good example. Existing tools will be assessed and scaled up to provide the necessary flow of funding. The capital base of the KfW will be assessed and potentially expanded. Cooperation with the EIB may provide one route.

On the debt brake specifically the agreement states:

Debt retirement for the excess deficits of 2020-2022 will be regulated according to an amortization plan approved by the Bundestag. This will incorporate also the Next Gen EU funds.

In future, special funds will be accounted for under the debt brake on a 1:1 basis. This sounds like a restrictive decision but may have the opposite effect. Hitherto both Federal injections into these funds and payments out of them were counted as expenditures, which apparently resulted in double counting. On the hand, any top-up payments by the Federal governments to funds (Sondervermögen) will count against the debt brake. Longer term this seems like a restrictive safeguard against “off balance-sheet measures”. Was there some deal done between Lindner and Habeck?

The supposition was always that this would be organized through “special funds” that were under the direction of a super Ministry for the Economy and Climate. That is now Habeck’s job but what funds does he have at his disposal?

The coalition document states: “The current energy and climate fund (EKF) will be developed into a climate and transformation fund (KTF). In the 2021 budget, borrowing authorizations already approved but not yet used will provide an inflow of funding to the new KTF.” This will help to energize the energy transition and make good investment foregone during the crisis period.

As Philippa Sigl-Glöckner notes, this sounds expansive but amounts to funding long-term expenditure out of short-term, one-off financial flows.

Vorläufige(!) Takeways zu 🇩🇪 Haushalt & dem 🇪🇺 Stabilitäts- & Wachstumspakt im #Ampel #Koalitionsvertrag. TLTR: Notlage + geänderte Berechnung des Defizits erhöhen den fin. Spielraum, Beträge werden nicht genannt. Bei EUR mehr Offenheit als ich dachte. https://t.co/6WXdevYwI3 /1

— Philippa Sigl-Glöckner (@PhilippaSigl) November 24, 2021

For the future, the coalition agreement promises merely that in the budget for 2022 “we will assess how the climate and transformation fund can be reinforced within the limits of the constitutional provisions”, i.e. the debt brake.

One way out of this impasse may be to reassess not the debt brake as such but its operation. On the basis of 10 years of experience, including systemic crises, the coalition agreement says that it is time to review the cyclical adjustments methods used to define how tightly the debt brake binds at any given moment. As several experts have noted this may provide a way to work around the tight provisions of the debt brake and enable low-cost public borrowing.

The coalition agreement gives no details. Instead it goes on to emphasize that all expenditure will be reviewed, reprioritized and directed in a transparent way towards the achievement of the coalition’s goals.

One promising proposal is the creation of a comprehensive inventory of public assets to properly account for depreciation and guide investment and maintenance expenditure. Strikingly, this is presented as a contribution to intergenerational fairness. This is significant because it is normally only debt that is discussed as a burden on future generations. If rather than fewer debts, it is a healthy public balance sheet that must be passed to future generations, that would be a step in the right direction.

The new government also promises to reduce any financial commitments (Geldanlagen) that are incompatible with its climate goals.

The issuance of green bonds will be encouraged.

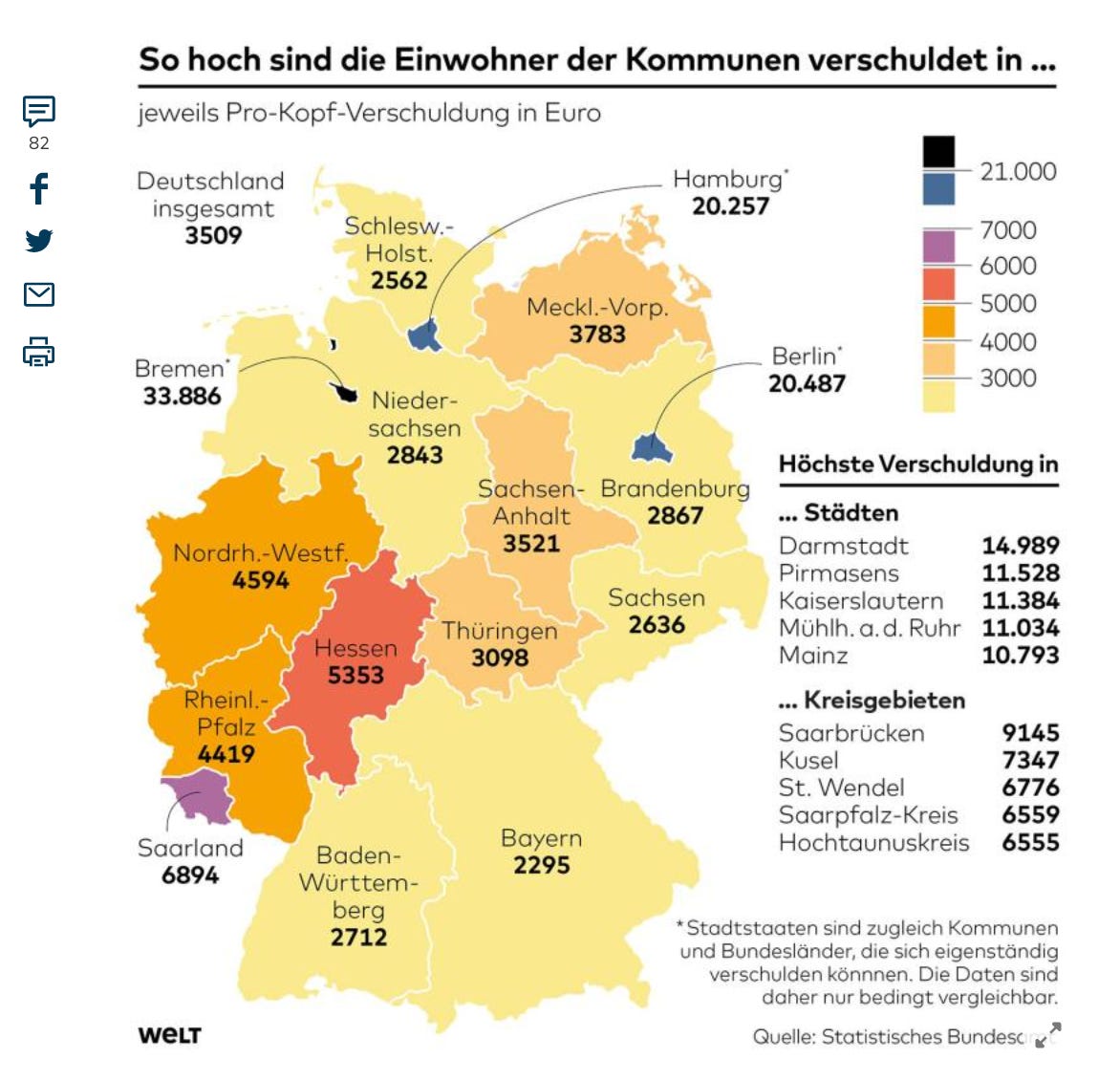

One unglamorous but important measure is the commitment of the new government to achieve a comprehensive financial restructuring of local government debt. As former mayor of Hamburg, Scholz was heavily involved in the federal aspects of finance. A priority of his government will be to provide a solution that puts communes with overwhelming burdens of legacy debt, on a more viable basis.

Sour

Source: Die Welt

These debts are a source of much local tension over the inability to afford essential welfare payments. If local government is to be part of the public investment push, those crippling debt levels must be lifted. This will require a common and one-time effort of the federal government and those states whose communes are afflicted by this problem. This will require a constitutional amendment and a deal with the CDU/CSU. It will be capped by a new system of monitoring to prevent any backsliding into unsustainable debts.

Conclusion?

Clearly, it is far too early to make any overall assessment. Lindner as Finance Minister is a major threat to any progressive ambition on the part of the government. I stick to that judgement and hope to be proven wrong. Much will depend on who advises him at the Ministry. German economics is not the conservative monolith it once was, one can only hope for the best. The FDP’s coalition partners are certainly aware of the risks.

More generally Germany’s new government is important to watch because it promises to continue the process of adapting and modernizing a European nation-state that began in the 1960s and is now a multi-generational project. The Social Democrats, the Greens and the liberals have been important parts of that process, whether in the social-liberal coalitions of the 1970s and 1980s or as Red-Green. Merkel’s modernization of the CDU owes much to her borrowing from the SPD. This is a government that embraces the climate challenge and has the political backing to do something about it. It has no excuses. Germany is pivotal to Europe’s climate ambitions. And, more generally, the success or failure of this government will tell us a lot about the capacity of sophisticated democracies around the world to adapt to our 21st-century polycrisis.