A lackluster battle leaves Europe hanging in the balance.

The German election on September 26 to decide the successor to Angela Merkel has been a lack-luster affair. Nevertheless, the vote and the coalition negotiations will have decisive significance, not just for Germany but for Europe.

In a piece in Foreign Policy that came out on Friday I mapped some of the faultlines that have been exposed.

At the center of the story is the recovery, in relative terms of the Social Democrats.

Wenn am nächsten Sonntag #Bundestagswahl wäre, würden 27% die #SPD wählen (+2). Damit bauen die #Sozialdemokraten ihren Vorsprung vor der #Union weiter aus, die bei 21% verharrt. Alle anderen Parteien stagnieren oder verlieren an Zuspruch https://t.co/1l6la0TScs #btw21 #wahl2021 pic.twitter.com/YMxXPic1Vi

— Ipsos Germany (@IpsosGermany) September 17, 2021

If the SPD were to achieve 27 percent it would be a good result, but hardly stunning by historic standards. What would be stunning would be a collapse of the CDU to 21%.

The CDU’s candidate, Armin Laschet, has proved a dud. The party lacks programmatic direction. Its electorate is unenthusiastic.

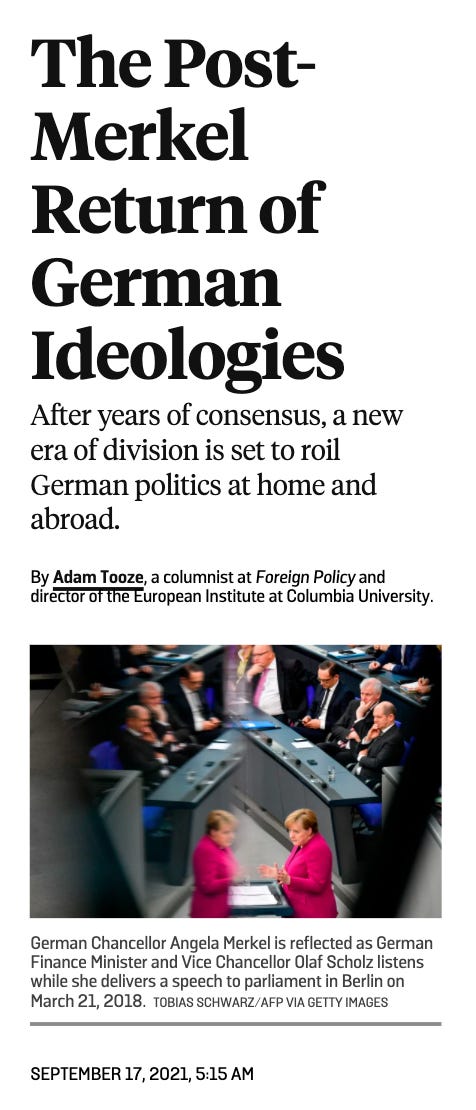

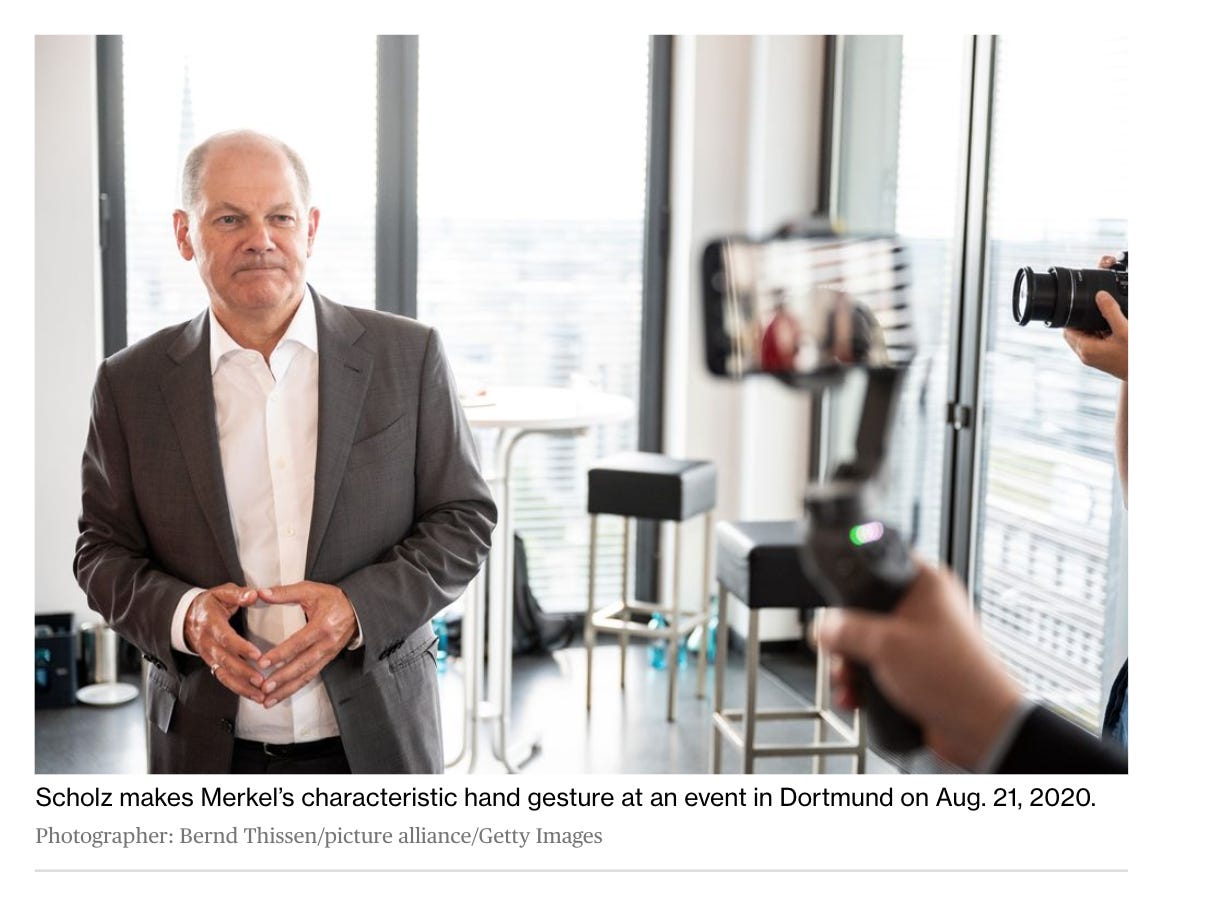

Olaf Scholz has cannily positioned himself as the successor to Merkel. Even going so far as to adopt her famous diamond-shaped hand gesture.

Insofar as Scholz has positioned himself ideologically, it is around terms like “respect” and the need for greater solidarity. He steers clear of the big structural issues. He has avoided taking a strong stance against the debt brake. He has not been a driver on climate policy.

Nevertheless, as the SPD have come to the fore, what has been remarkable is the aggressiveness with which the CDU/CSU have pushed back. They have revived an anti-socialism of the Cold War era.

Time is a flat circle… pic.twitter.com/PG5ccvOArn

— Ned Richardson-Little (@HistoryNed) August 31, 2021

Rhetorically, the CDU’s “red scare” campaign focuses on the possibility of a coalition between SPD-Greens-Die Linke i.e. the three left-wing parties. In recent attacks they have focused not just on the Communists associations of the left-wing Die Linke, but on the SPD’s own opposition to West German alignment with Europe and NATO in the 1950s. The CDU/CSU have reminded voters that in 1989 the then leader of the SPD, the left-wing Oskar Lafontaine (future father of Die Linke), was anything but enthusiastic about German reunification.

These attacks are wildly off mark as far as Scholz’s own inclinations are concerned. It is also absurd to accuse the SPD, Die Linke and the Greens of aspiring to a revolutionary transformation of German social conditions. But they do, in fact, agree on key domestic priorities: public investment, redistributive taxation, climate. They do favor a rebalancing of German society, which has always been marked by pronounced wealth inequality and in recent decades has seen a surge in precarity and income inequality. Red-Red-Green also agree, to a large extent, on Europe too. They favor a more expansive fiscal stance and show no inclination to rock the boat on European debts.

Red scare tactics aside, in programmatic terms of all the possible coalitions, Red-Red-Green is least likely to be riven by deep ideological divides. In several states in both East and West Germany, R2G coalitions are currently in control without the sky having fallen. The full map of state-level coalition possibilities in Germany gives you an idea of the complexity of its politics.

Noch bunter: Mit der neuen Landesregierung in @SachsenAnhalt ändert sich auch die Zusammensetzung des #Bundesrates – die Länderkammer wird um ein neues Koalitionsformat ⬛️🟥🟨 reicher: https://t.co/KcAeZ79ZUr pic.twitter.com/wJShlQxdyd

— Bundesrat (@bundesrat) September 16, 2021

What makes Red-Red-Green dangerous for the SPD and the Greens at the national level are not only the vituperation of the right against Die Linke but splits within the ranks of the SPD and the Greens themselves.

Both the SPD and the Greens have been marked by left-right splits that go back to the 1980s and beyond. Die Linke emerged in 2005 out of a split within the SPD over the neoliberal turn of the party under Gerhard Schroeder. I traced some of that history in a long read for the LRB back in 2019.

In the 2000s, Olaf Scholz was a loyal lieutenant of Schroeder. He has since distanced himself from the controversial Hartz IV welfare system. But that does not mean that Scholz has any sympathy for Die Linke.

Whilst they agree on domestic policy, on environment and on Europe, Red-Red-Green would likely be at odds over foreign policy. Much is made of Die Linke’s hostility to NATO and their friendliness towards Russia. The gap on foreign policy is probably largest to the Greens rather than the SPD.

The data is pretty clear about the chasm between left and greenshttps://t.co/Y7PRCwK1vR

— Lamarckìan Perspective (@CPIM_Lamarck) September 7, 2021

All in all foreign policy is less a real obstacle to the coalition than a convenient excuse for Olaf Scholz to avoid discussing the option too seriously. He wants to keep the possibility open, but he does not want to be identified with a left-wing alternative for Germany.

The coalition that Scholz would clearly prefer is “traffic light” – Red-Yellow-Green – SPD-FDP-Greens. This would be politically safe for both the Greens and the SPD. The FDP would absorb bullying from the right by the CDU. But can it actually function as a government?

The FDP are the true wildcard of this election.

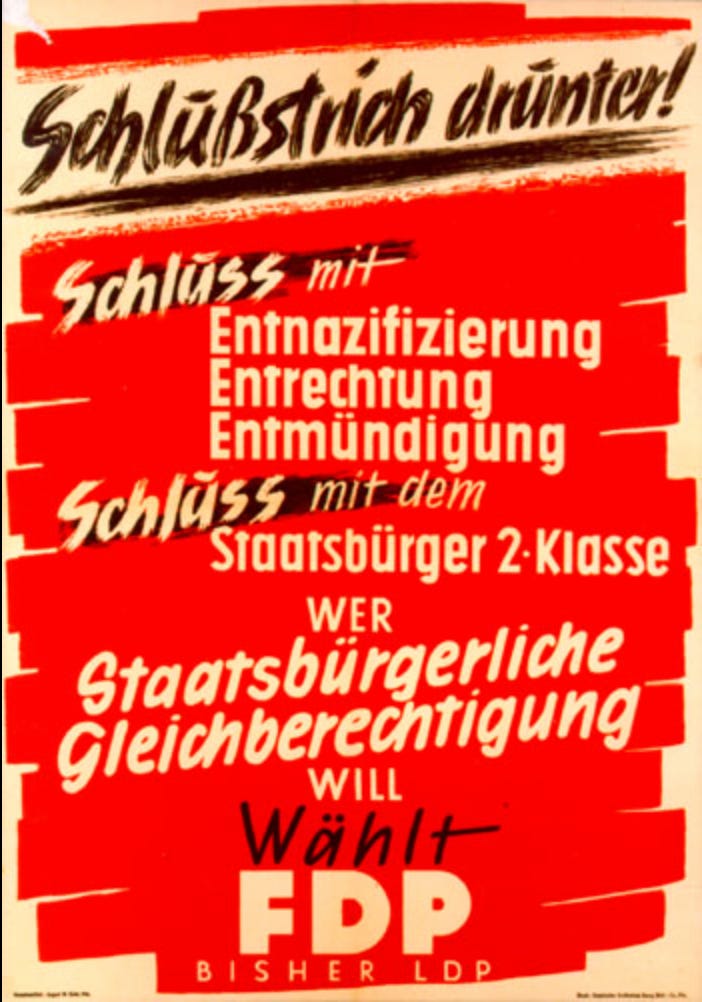

Like the CDU and the SPD, German liberalism has a lineage that can be traced back to the 1860s and beyond. After World War II, today’s FDP was formed out a merger of the left liberal DDP and the more business-friendly and nationalist DVP. The party was an amalgam of social market economy ordoliberalism and nationalist resentment. In the 1950s and 1960s the FDP were the party with the densest concentration of ex-Nazis. This notorious poster calling for an end to denazification is not unrepresentative.

In the late 1960s the party opened itself to the possibility of a coalition with the SPD and under Brandt and Schmidt with Genscher as foreign minister it helped to anchor Ostpolitik, detente with the Soviet Union and a social liberal program of domestic reform.

As the indispensable coalition partner in the old three-party system of the Federal Republic, it was the FDP that then also decided the fall of Schmidt’s government in 1982 and Kohl’s accession to power.

From 1949 to 1998 the FDP were arguably the pivot of the entire West German political system. But in the 21st century the FDP’s wilderness years began. Between 1998 and 2005 the SPD ruled with the Greens. And then, in 2005, with Merkel as leader, the CDU opted for a coalition with the SPD – as she would do for three of her four governments. Only in 2009 did the FDP return to power, in a government whose period in office (2009-2013) was dominated by European crises which divided the FDP.

In 2017 Merkel wanted to reform her government on the basis of a “Jamaica coalition”, together with the FDP and the Greens. But after weeks of talks, Christian Lindner the mercurial leader of the FDP bolted. This forced Merkel back into the grand coalition and sent the SPD into a tail spin as what was left of its youthful, left-wing base protested against the decision to prop up Merkel yet again.

It is worth reminding ourselves that it took a full 6 months for the coalition deal to be finally done between the SPD and the CDU in March 2018. It could be 2022 before the successor to Merkel is finally decided.

Once again we face the question: Is the FDP under Lindner willing to accept the risk of a three-party coalition with the Greens?

“The prerequisite for us joining any coalition is that we can’t have tax increases and we respect the constitutional debt brake,” Christian Lindner, told the Financial Times. “Whoever wants to do something else will have to look for another partner.” How on that basis is a deal to be done with the SPD and the Greens both of whom are promising substantial public investment programs? The Greens are openly calling for a revision of the debt brake.

Perhaps the FDP, SPD and Greens could agree on big investments in infrastructure, climate and digitization. But the question would come down to financing. SPD and Greens would raise debts. Germany can after all borrow at negative rates. Lindner insists on private financing and advocates selling off of the German government’s stake in Deutsche Telekom and Deutsche Post to “pay for” investments. Holding the line on tax increases is a fetish for the FDP.

In whatever coalition emerges, who holds the Finance Ministry job is critical, as Olaf Scholz and Wolfgang Schäuble in their own way have both demonstrated. Lindner clearly knows it too. In the election he has posed the question: would you prefer Robert Habeck the Green #2 as German finance minister, or me?

Unsurprisingly, given these difficulties, Lindner has announced that he would prefer a Jamaica coalition with the CDU and the Greens. For the CDU to provide the Chancellor after coming second to the SPD in a historic defeat is hard to envision. One can on the other hand see why it is attractive to Lindner. It would give him maximum leverage within a coalition with two enfeebled and disappointed partners. It cannot be ruled out, but unless the CDU does far better than the polling suggests, it will not be the first option. At a minimum if it comes to this unattractive combination, it is the Greens who should insist on taking the Finance Ministry portfolio, anything else would be a recipe for total betrayal of their agenda.

How the coalition arithmetic works out is critical, not just for Germany but for Europe.

In Europe the FDP caucus with ALDE, but that grouping is highly diverse, ranging from the formidable Margrethe Vestager to the obstructive Mark Rutte of the Netherlands. Lindner’s FDP contains a solid group of Eurosceptics. The party was divided during the eurozone crisis. Lindner himself is pro-European, but his vision of Europe centers on restoring the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact – i.e. the rules that limit debt as a share of gdp and deficits as a share of gdp. As Lindner told the FT: “Over the past few years the Maastricht criteria have shown themselves to be appropriate and sufficiently flexible,” he said. “For that reason, the eurozone should work towards reinstating them, and soon.”

He aims to reduce disparities between EU members but not through transfers but through investment. Lidner does favor “common European banking and financial market”, and, in the words of the FT “seemed open to a common deposit insurance”. But then added: any such a scheme “must take into account the special situation of German savings and co-operative banks”. And they have been the main brake on reform.

The FDP’s actual manifesto is even more hardline. It calls for tough deficit and debt-to-gdp ratios and wants to “tighten sanctions”. Europe’s leap towards fiscal federalism in 2020 is to remain an exceptional crisis response. Any common European taxation is ruled out.

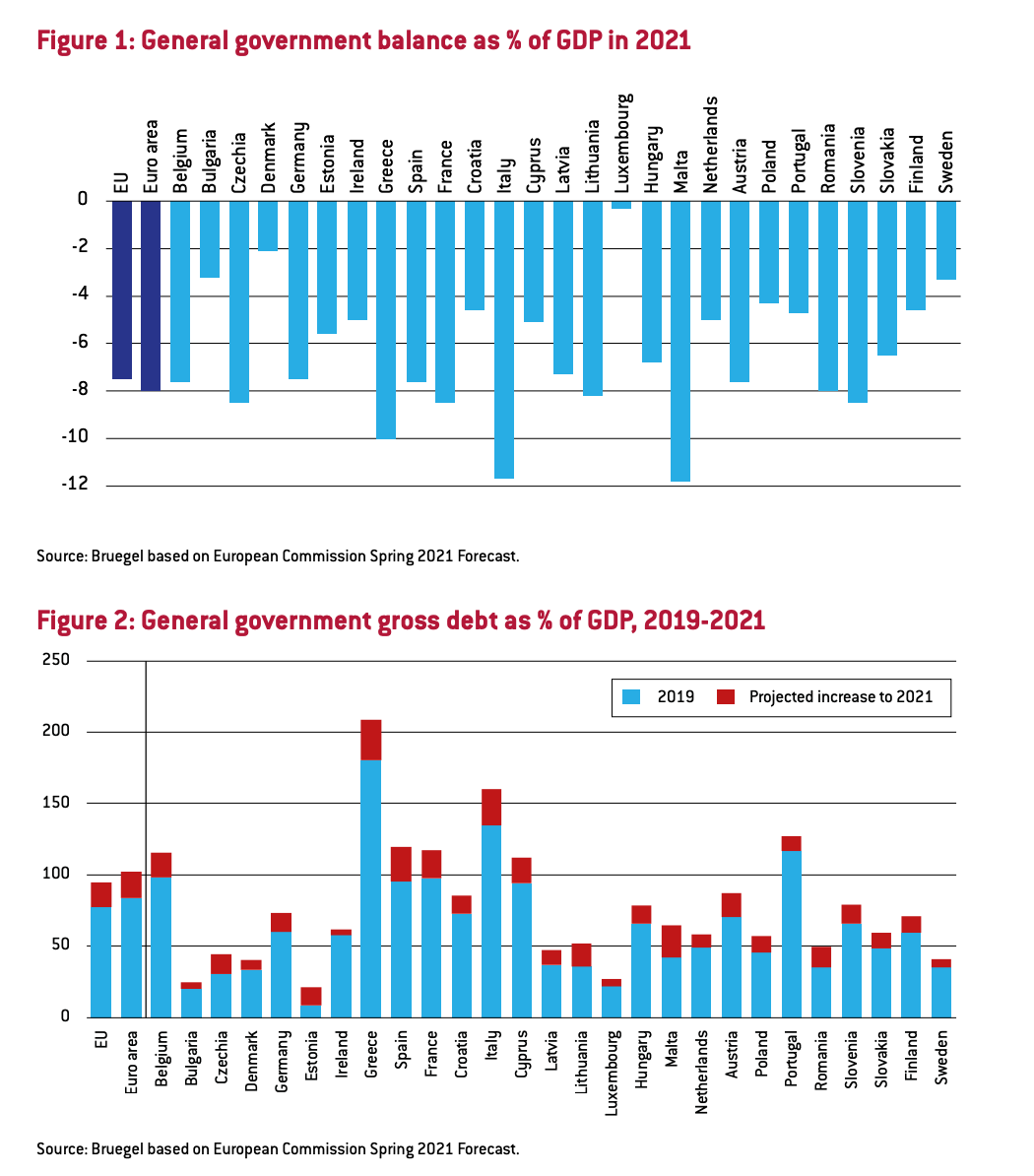

In light of Europe’s current debt levels, as a powerful Bruegel paper by Zsolt Darvas and Guntram Wolf makes clear, any precipitate push towards fiscal consolidation would be disastrous. It would negate any effort to drive forward the European energy transition.

That, however, seems to be precisely what the FDP envisions. It is all the more alarming for the fact that a coalition of fiscally conservative governments is ready and waiting for a conservative turn in Berlin.

As the FT concludes, if Lindner were to become Germany’s Finance Minister, its European partners “can’t say they weren’t warned”.

******

A quick note about Chartbook. I enjoy putting the newsletter together and I am delighted that it goes out free to many readers. But if you can afford to show your support, there are three options:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.