Grasping for ways to connect the crises.

This week, two crises taking place simultaneously, affecting some of the most vulnerable people in the world – the Taliban conquest of Afghanistan and the earthquake in Haiti.

These two moments in history seem as though they are unfolding on planets that are remote from each other.

They are, of course, very different events.

Telling myself this, helps me to feel less uneasy about the extraordinary amount of attention I am focusing on the events at Kabul airport rather than on the earthquake that has killed at least 1900 people and injured 10,000 in Haiti, a close neighbor in the Caribbean.

I am not, of course, suggesting that an earthquake and a war are the same or should be treated as such. But, I am wondering at the different mental silos into which we place them and the way in which one has eclipsed the other.

After all, Haiti is reeling under the impact not just of natural disasters – an earthquake and a tropical storm. In the months preceding that it had been rocked by political turmoil, following the July 7 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse.

The retreat from Afghanistan is a cause of deep soul-searching, whereas the on-going poverty, dysfunction and violence in Haiti is simply the status quo. Even setting aside the broader US entanglement with the Caribbean, under Clinton, Bush and Obama, the US made massive interventions in Haiti. In 1994 this involved 25,000 soldiers and an aircraft carrier.

Right now, USAID is scrambling expert personnel to Haiti and concerned people in Congress will mobilize for a push to provide financial aid. But reading Biden’s speech on Afghanistan, I find myself wondering whether the ultimate aim of the Biden’s administration policy might not be characterized as the reduction of Afghanistan to the scale of Haiti on Washington’s radar screen,

If that is the case – no more than an “if” – what then is the category to which both are consigned? How far removed are we from Trump’s unspeakable classification of the countries of the world?

You could also say that this is another way of wondering about the change that has come over US politics.

Not so long ago, in Washington DC, Haiti and Afghanistan were commonly evoked together. Both were classed in the category of high priority targets of intervention. What joined them together was the word that may not be used in the White House in 2021, what American forces were not “supposed” to be doing in Afghanistan i.e. “nation-building”.

If you return to the documents from the early 2000s in which not Bush appointees, but former members of the Clinton administration sought to synthesize and make sense of America’s foreign interventions, from postwar West Germany and postwar Japan to Iraq, there they were – Haiti and Afghanistan – side by side, stepping stones on the path from 1945 to 2003.

The personal link between the two Presidencies and the two interventions was James F. Dobbins, Clinton administration’s special envoy for Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo, and, in the aftermath of 11 September 2001, the Bush administration’s special envoy for Afghanistan. He served as Assistant Secretary of State for Europe, Special Assistant to the President for the Western Hemisphere and Ambassador to the European Community.

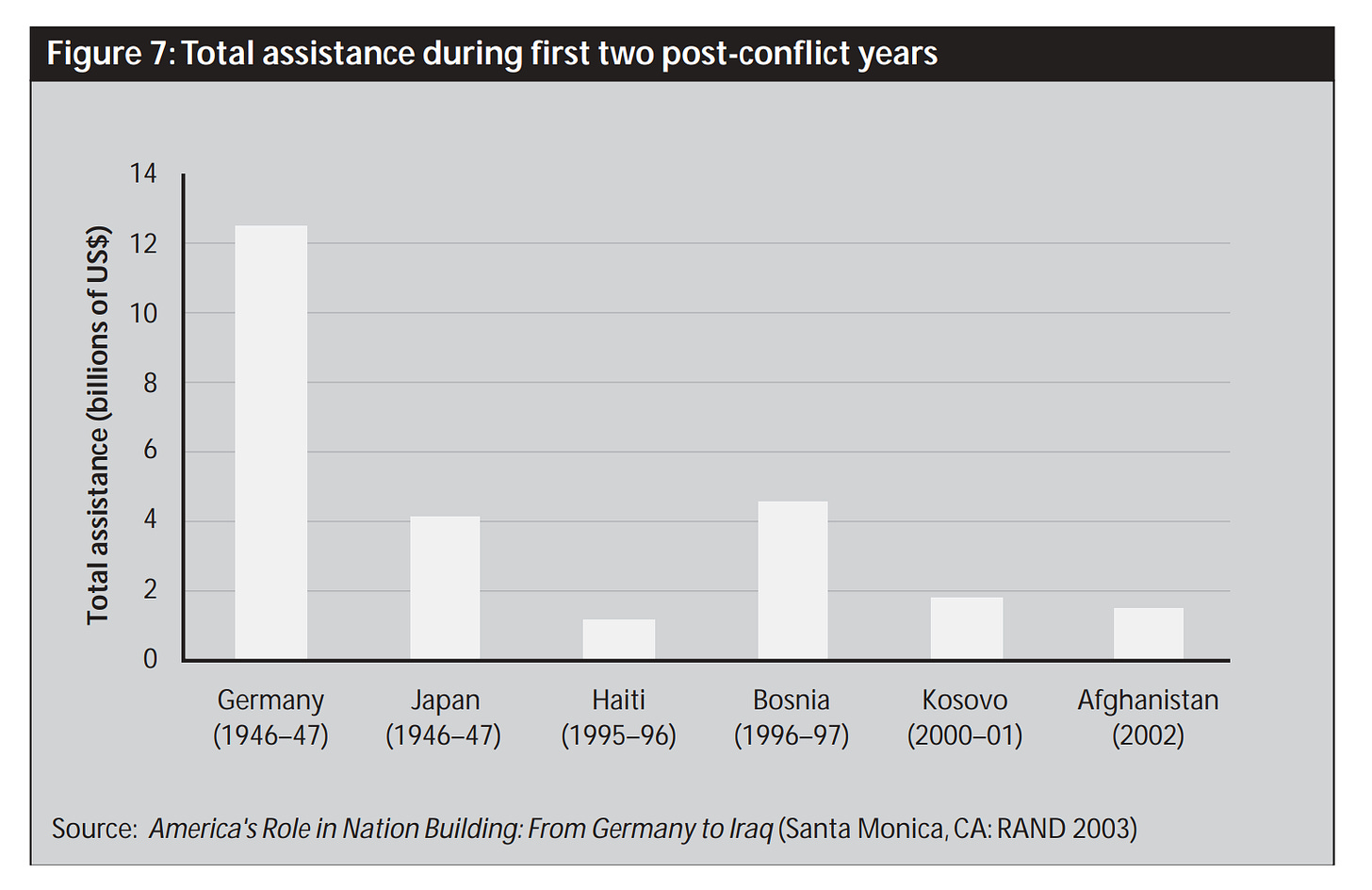

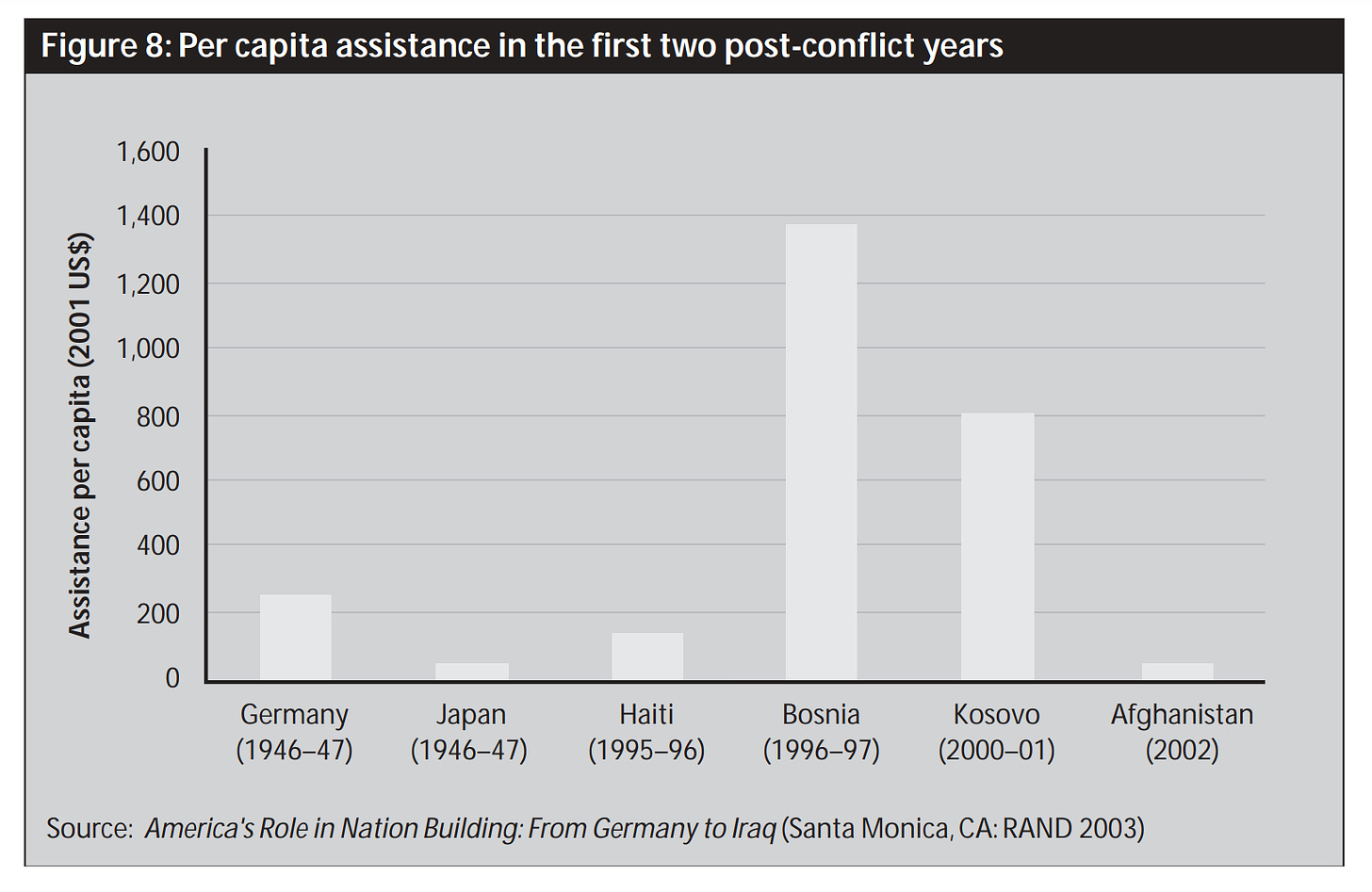

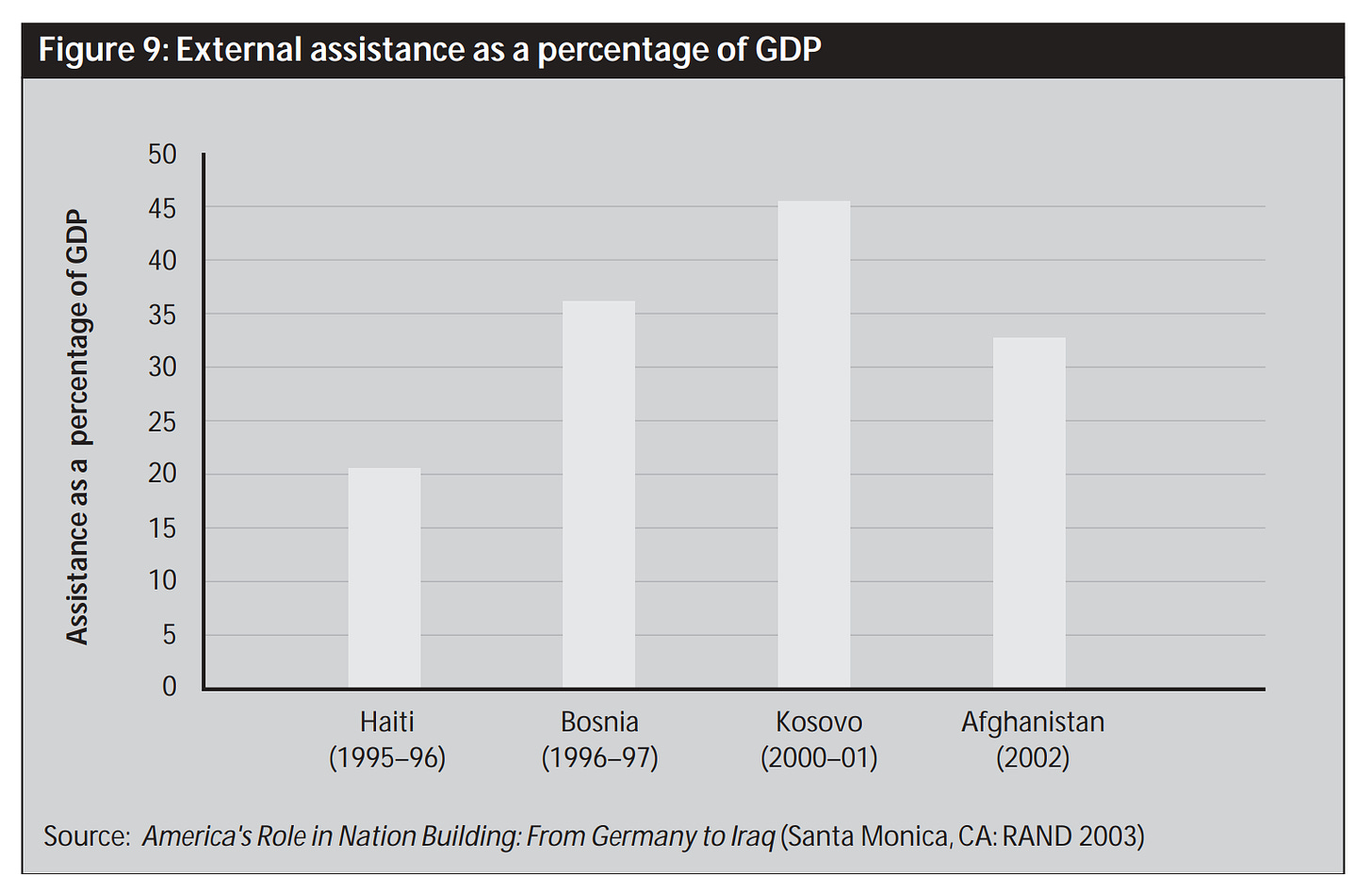

In 2003 Dobbins was Director for International Security and Defense Policy at the RAND Corporation. In the RAND report that he helmed, the Haiti and Afghanistan interventions were directly benchmarked against each other, along with the other major nation-building efforts.

Source: RAND

In light of present events, how should one read these numbers? Do they tell us that the effort in Afghanistan in its early stages was too small? Or that the effort in Haiti in the 1990s was quite large? Perhaps both.

For the then Senator Biden it was clear already in the 1990s that the effort in Haiti was misguided. As he notoriously remarked in 1994: “If Haiti – a God awful thing to say – if Haiti, just quietly sunk into the Caribbean or rose up 300 feet, it wouldn’t matter a whole lot in terms of our interest.”

For the rest of that very revealing interview, see this account from Newsweek, complete with video. It says a lot about how Biden at the time viewed both American foreign policy and its relationship to American domestic politics, a questions which continues to occupy the administration today, though the term is now “foreign policy for the American middle class”.

What Biden opposed in Haiti in 1994 was an intervention that seemed to usher in a new era.

Following several years of political violence and turmoil in Haiti, under considerable pressure from the Black Caucus in Congress in 1994 the Clinton White House launched a military intervention and reconstruction effort. This was not like those after 9/11. It was not triggered by an immediate need to retaliate for an attack on the US. The intervention was driven by more general concerns. As the official historian of the State Department reports, “On July 31 the Security Council passed UNSCR 940, the first resolution authorizing the use of force to restore democracy for a member nation.”

The intervention in Haiti that Biden opposed was the original expression, if one can speak of such a thing, of 1990s unipolar self-confidence. It was the original “regime change” moment. In the Caribbean. In Haiti.

At first, the intervention was considered a success and Clinton was urged to consider something similar in Afghanistan too. If America brought peace and put an end to the warlord chaos it would forestall a slide towards Taliban-rule. On the Afghanistan option Clinton demurred. As the 9/11 Commission reported, by the late 1990s, whilst the CIA and Justice Department were hunting Bin Ladin, “the State Department was focused more on lessening Indo-Pakistani nuclear tensions, ending the Afghan civil war, and ameliorating the Taliban’s human rights abuses than on driving out Bin Ladin. Another key actor, Marine General Anthony Zinni, the commander in chief of the U.S. Central Command, shared the State Department’s view.”

After Somalia, Haiti and Bosnia, by the late 1990s the enthusiasm for large-scale reconstruction interventions was wearing thin. It was that disillusionment which caused George W. Bush on the stump, to criticize nation-building and, later, to soft pedal any such ambition in Afghanistan.

On the ground in 2001-2, the Bush administration would, in fact, push for expansive reconstruction plans, but it counted on the UN and NATO to pay. America was pivoting to Iraq. And in both Iraq and Afghanistan the Bush-era strategists expected the private sector to deliver on a huge scale. Amongst the ruins, disaster capitalism would thrive.

Neither in Haiti or Afghanistan did it prove possible to realize the goals of the intervention and then to effect a clean exit. Instead, what resulted were prolonged, extensive and often highly dysfunctional engagements. Whatever the US were initially supposed to be doing, it did de facto become involved in nation-building in both places. And this engagement surged under the Obama administration, in Afghanistan in 2009 and in Haiti from 2010 following the devastating earthquake.

To trace the threads that weave Haiti and Afghanistan together in American policy and world history over the last two decades, through the Bush, Obama, Trump and Biden administrations, is far more than I can do here.

The story of the Clintons in Haiti continues down to the present. For details, see this long read in the Guardian and this level-headed account from the BBC.

Salacious details aside, the “Clintons in Haiti” saga points to a more general point. State-building acquires the momentum that it does, often because it is not so much a state that is being built but a complex of para-state agencies, propped up by businesses, foreign government agencies and NGOs invested in every sense of the word in the ongoing management of the crisis.

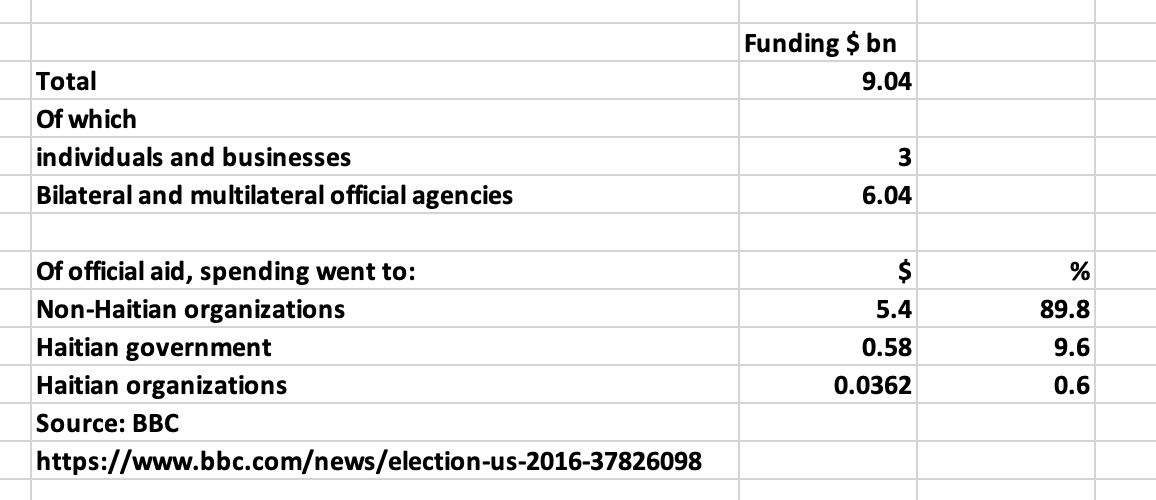

Total Aid Flows “to Haiti” Jan 2010-June 2012

Both in Afghanistan and Haiti the large spending figures should not be confused with money that actually stayed in place locally or was paid to the national government or local agencies. The vast majority of the money never touched the budgets of the respective national Treasuries. It simply recycled in the contracts and pay checks paid out to foreign workers on the ground. There is nothing per se incriminating or inappropriate about this. If foreign contractors actually deliver their services, then the receiving economy benefits at least from those. But it is important to understand this cycle to understand what the political economy of aid is driven by and why its impact on the ground is less than one might imagine.

If a blow by blow history is too much for now, alternatively, one could attempt a comparison based on systematic criteria, assessing points of similarity and difference. Why did Afghanistan come to occupy such a central place and Haiti fade away? Race? Terrorism? Geopolitical location? Religion?

You might say that Afghanistan matters because it is a geopolitical fracture zone, it was the source of the 2001 attack, it is Muslim and because Westerners find Hazari children adorable. On those same criteria, Haiti is classed as a second-order priority.

You might also ask, how robust is such a categorization? Imagine the gothic national security planning visions that might be spun by flipping each of those criteria. For sake of argument imagine a Pentagon planner sitting down to devise a scenario in which: “Haiti in 2031 is in the grip of an alien religious cult, harboring marauding bands of eco terrorists, attacking Western tourists across the heavily defended border to the Dominican Republic and launching drone strikes on Gulf of Mexico oil installations, or Miami, less than 700 miles away, funding themselves by smuggling the latest generation of genetically engineered ultra-addictive cocaine, in partnership with Central American cartels and Haitian diaspora connections across the urban centers of the United States”.

Haiti morphs into Black Afghanistan – a cli-fi scenario for ten years from now.

My point is not that this is a sensible exercise. My point is that if you embark on the exercise of classification and categorization you can, as we seem to be doing right now, flip “Afghanistan” into the “Haiti” category – “irrelevant, poor, chaotic, remote”. But you can also reverse the operation and turn “Haiti” into an “Afghanistan in the making”.

I use the scare quotes because the entities involved in this mental operation may have little to nothing to do with the complex realities on the ground. They are a “threat vector” characterized by a certain set of parameters. The entire exercise is framed by historical and racialized imaginings of threat and danger. And if you view the world that way it can hardly be assumed that either place will remain in a steady state for long. “Seeing like a state” can be capricious.

You don’t “need” to know more than just that terrorism, or “religious extremism” is present – check – to know whether you should care. The benefit is that you compress information.

Economic data are also a way of compressing information in an extreme form. What do the economic statistics tell us about the unlikely pairing of Haiti and Afghanistan?

I must admit that my prior information on this was poor. Life expectancy: Afghanistan v. Haiti? Higher? Lower? Kudos to you, if you do have strong priors on that comparison. Thinking about it I realized that all I knew was that both Afghanistan and Haiti were very poor. “Right at the bottom”. In my head they were simply lumped together in a crude category, a mode of thinking we should, I think, seek continually to correct in ourselves.

If you feel confident that you don’t fall into that mode of thought, tell me your best guess as to relative infant mortality, or GDP per capita in Haiti and Afghanistan – take your pick as to any relevant indicator – and I will take my hat off to you.

In all honesty, I couldn’t do much better than “life, nasty brutish and short”. Not good enough! Bad thinking.

So what can we learn from the obvious sources. World Bank, UNESCO etc?

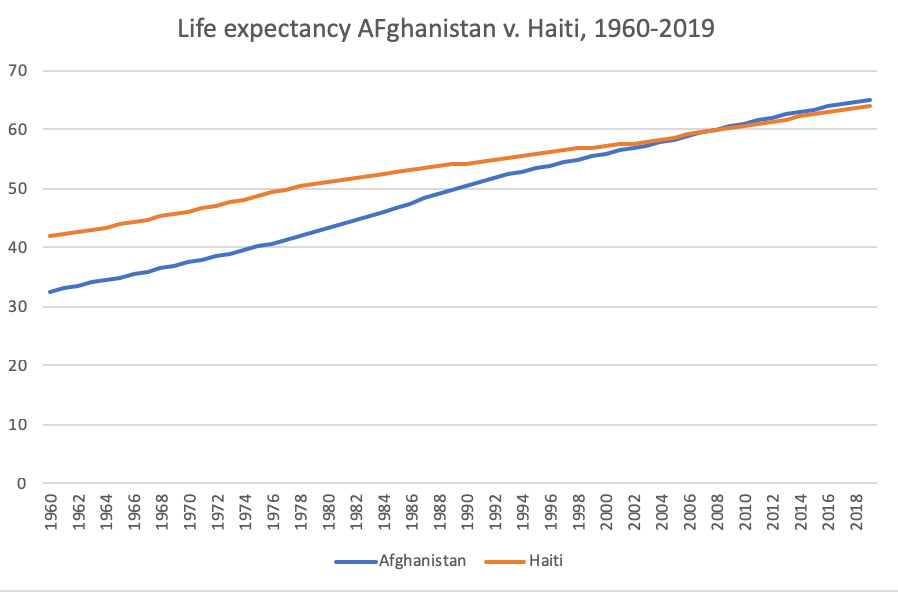

To take two basic indicators: life expectancy and maternal mortality. They both point to the fact that Afghanistan was initially a long way behind Haiti. Demographic data go back a relatively long way and they capture the extent to which Haiti was once integrated into the world economy far more directly than Afghanistan – on exploitative and unequal terms, of course – but nevertheless with productive effects.

Data Source: World Bank

Haiti’s development at least with regard to life expectancy has continued in a broadly positive direction, though at a grindingly slow pace. Afghanistan, from its terribly low base, has caught up. Despite the violence, in 2008 Afghanistan’s life-expectancy for the first time overtook that of Haiti.

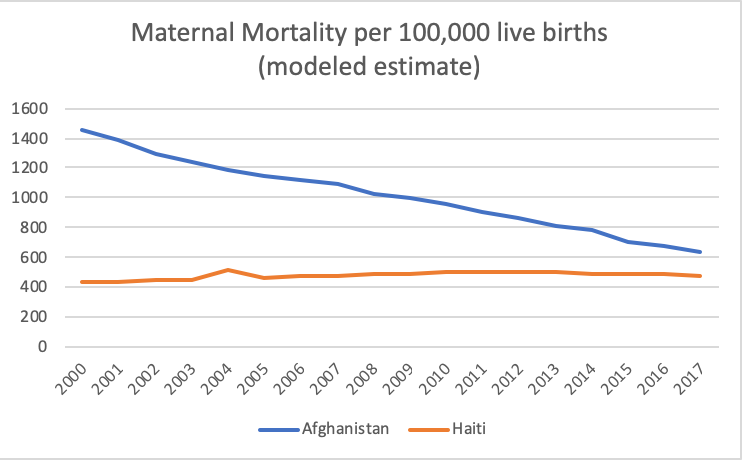

Source: World bank

The huge levels of maternal mortality in Afghanistan are telling. Inequalities along lines of gender are horrifyingly large in Afghanistan and they were so, long before the Taliban arose.

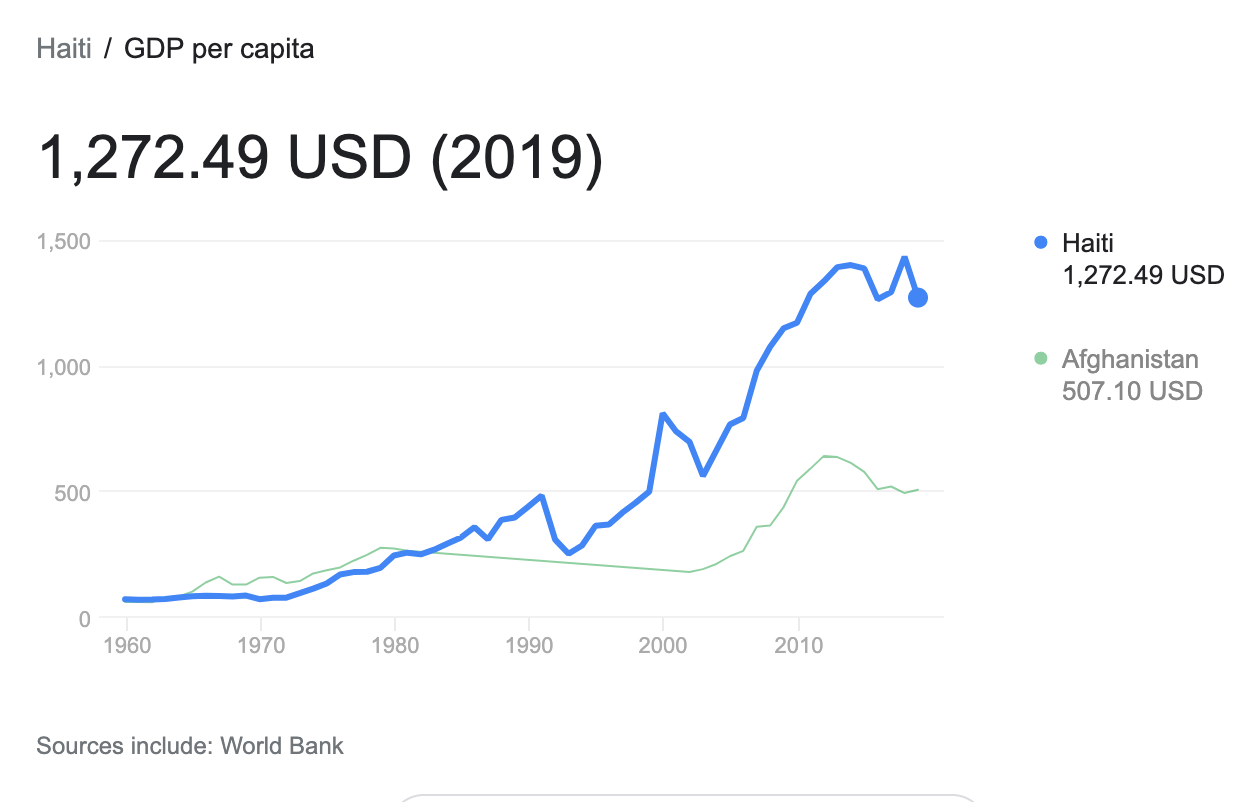

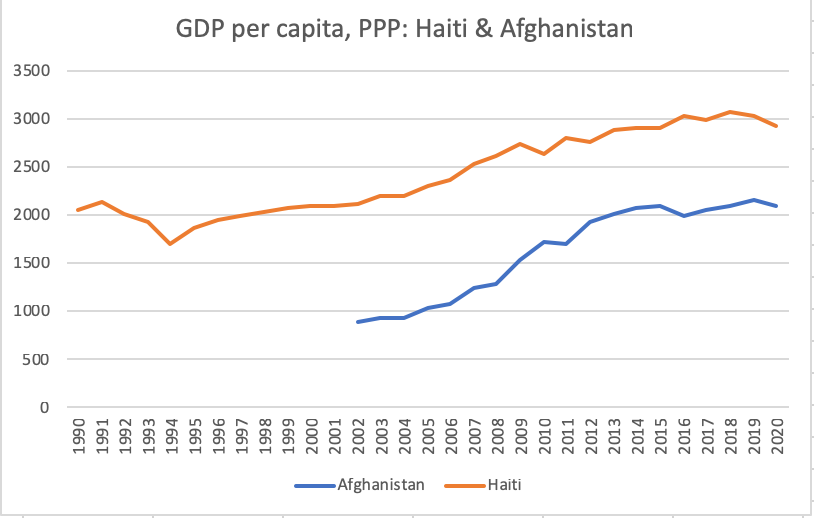

If you had asked me prior to conducting this exercise, where I though Haitian GDP per capita stood in relation to that of Afghanistan I would have been stumped.

What the numbers, in fact show is that despite Afghanistan’s convergence with Haiti in terms of mortality and life expectancy, it remains far behind in terms of the overall level of (measured) economic activity.

If you take GDP per capita at current exchange rates, the gap is very large indeed.

This represents the ability to “purchase” goods on global markets.

If you ask the question in terms of purchasing power parity, making allowance for the different internal cost of living, the gap closes somewhat, but remains very substantial.

The tens of billions in aid that flowed through Afghanistan over the last twenty years, did not manage to close the gap to Haiti. A humbling comparison if there ever was on.

You could also say that despite the dysfunction, corruption and disaster that has struck Haiti over recent decades, its location and long-standing integration into the Caribbean economy seems to confer resilient advantages. At least as a first approximation.

Tragically, in the last few years, both countries have been headed in the wrong direction.

Remittances play a large part in both economies, particularly in Haiti where they run over 20 percent of GDP. To avoid distorting the comparison, the measure being used here is Gross Domestic Product, which excludes remittances. The multiplier effects that come from spending the remittances locally is captured in the data. If the comparison were based on GNP it would be even more favorable to Haiti.

Using national averages in both cases is deeply problematic not only because the quality of the numbers is suspect but because both countries are characterized by huge income and wealth inequality. In Haiti, the Gini coefficient is a staggering 0.61, where 0 is absolute equality and 1 marks the most extreme inequality. That places it alongside South Africa as one of the most unequal places on earth. The data for Afghanistan are not reliable enough to make such a calculation very meaningful.

Both Haiti and Afghanistan are characterized by a huge gap between urban and rural incomes. The majority of the city inhabitants live in informal settlements. The Poverty rate in Afghanistan and Haiti is over 50 percent in both cases. Those are widely cited as drivers of the Taliban mobilization.

Another similarity is that both Afghanistan and Haiti are extremely vulnerable to major natural disasters, both in the form of seismic shocks and the more fast-moving timescales of the Anthropocene. Afghanistan has been plagued by drought, Haiti by devastating hurricanes.

One could go on. But that would not be in the spirit of the Chartbook project which is non finito. I wanted to put this idea on the table and see how far I am able to push it for now. What would an interconnected analysis of these two places, apparently so distant from each other, mean at this moment? How can we resist both of them being pushed off into a flattening category of irrelevance, or dumped into the box of which Ashraf Ghani, now safely in the UAE, was once a great expert, i.e.“failed states”.

Here, as a depressing coda, a 2008 meeting at which Ghani and his co-author Claire Lockhart discuss Haiti as an example of failed donor efforts to build an effective state.