Before signing off to finish Shutdown (out in September!) I was worried about Europe. I still think we should be.

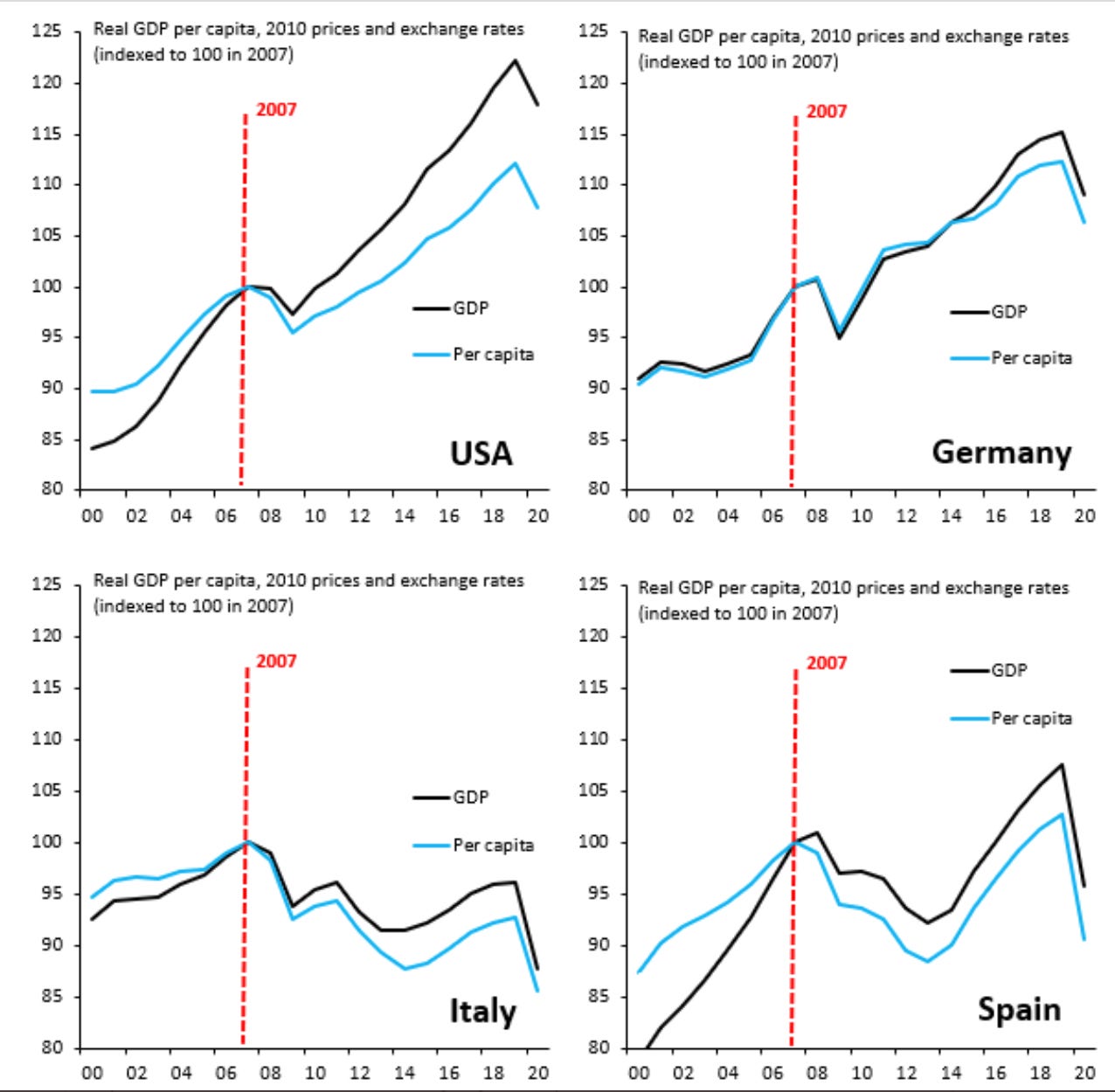

In 2020, the corona crisis delivered a devastating hit to both Italy and Spain . This comes on top of two previous shocks – 2008 and the eurozone crisis 2010-2013. The result is an alarming divergence in economic performance between the most troubled parts of the Eurozone, the rest of Europe and the United States.

Source: Robin Brooks, IIF Twitter

These graphs from Robin Brooks and the team at the IIF are particularly striking because they compare GDP and GDP per capita.

Adjusting for population growth reveals that German and American economic performance have been strikingly similar since 2000. Neither is exactly breathtaking, but they have achieved a 15 point increase in gdp per capita. By contrast, Italy’s performance once we allow for modest population growth is even more catastrophic. GDP per capita in 2020 was 15 percent below its 2007 peak. In Spain as well, GDP per capita in 2020 was barely higher than it was in the early 2000s.

The double dip recession of 2008-2013 was exacerbated by a pro-cyclical contractionary fiscal policy in Europe. That mistake was not repeated in 2020.

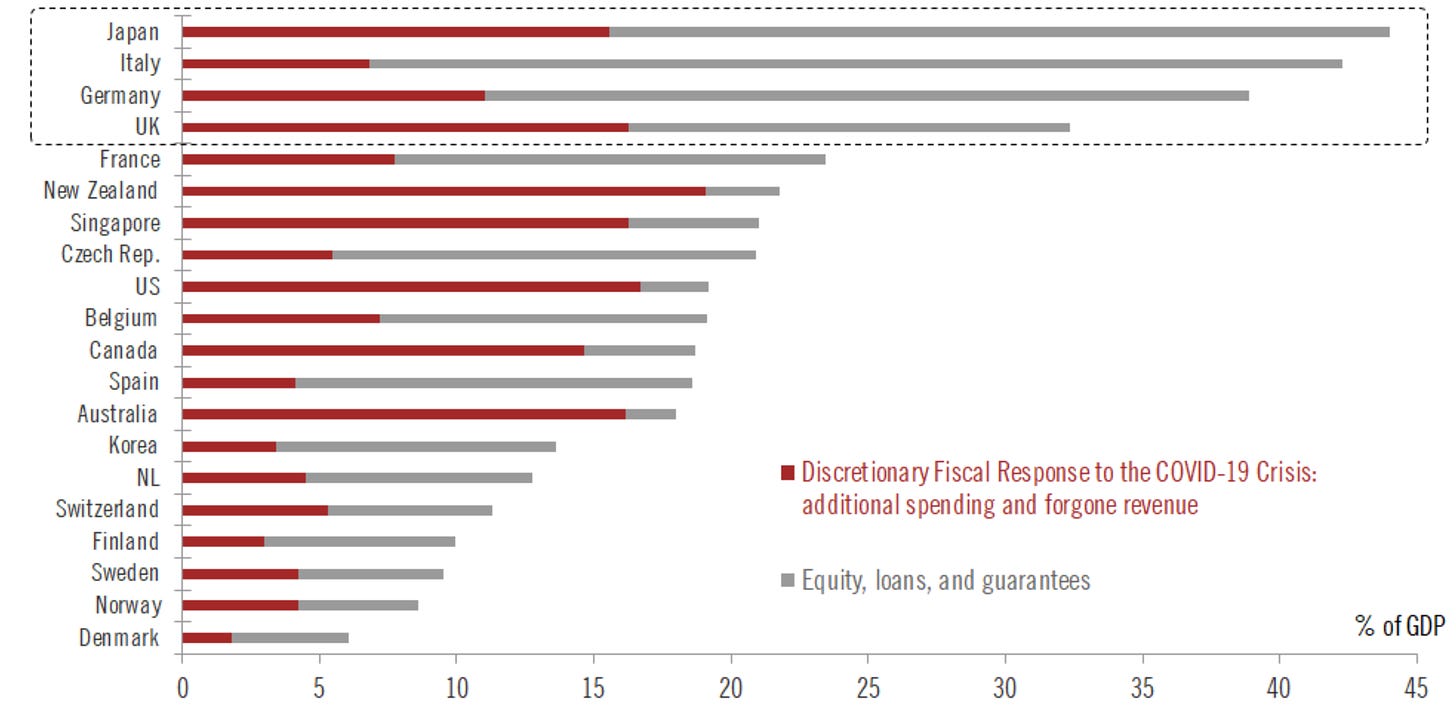

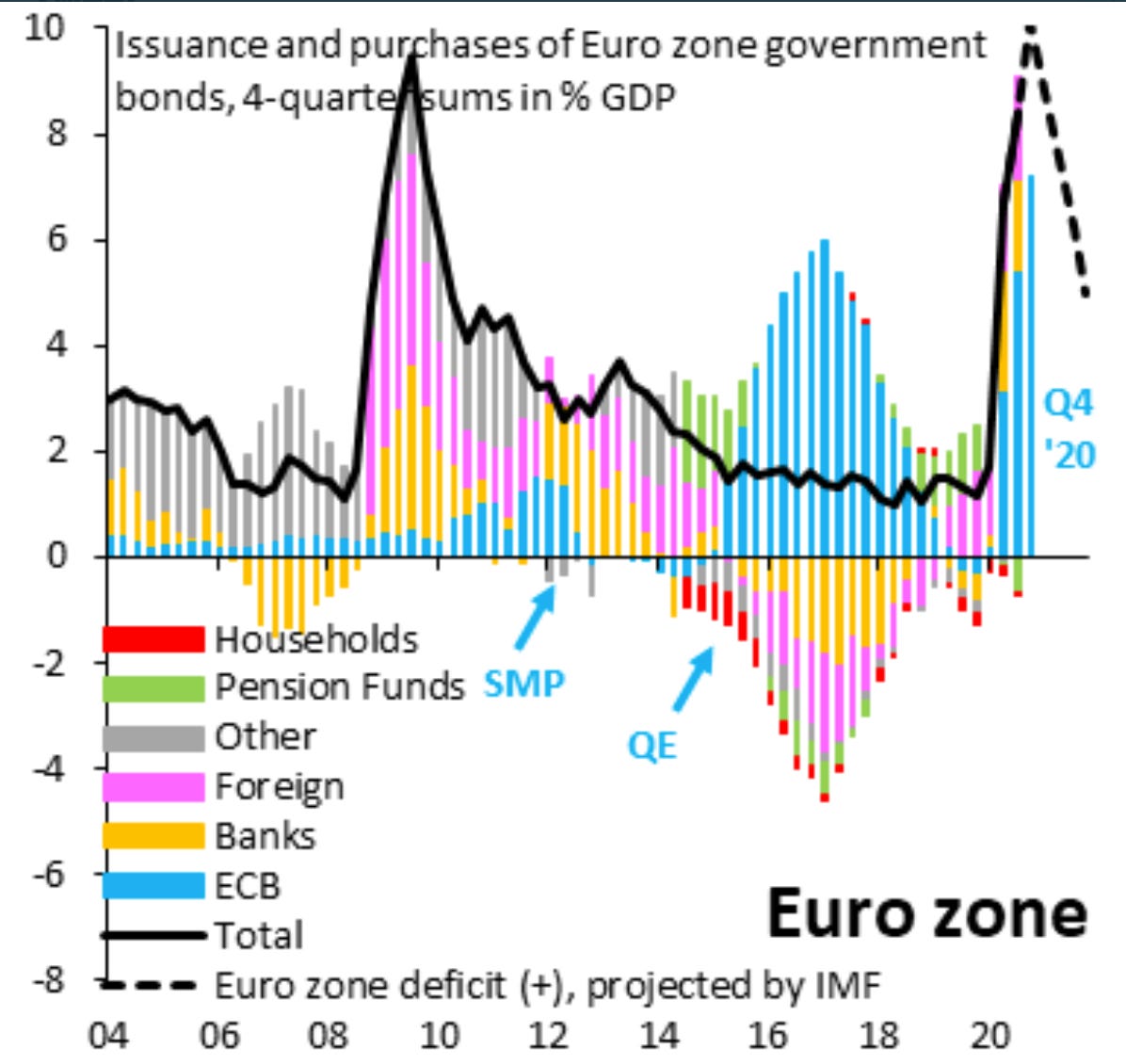

In response to the 2020 crisis there was unprecedented fiscal and monetary action.

As the latest release of data from the IMF, handily compiled by the indispensable Frederick Ducrozet make clear, though the European fiscal effort was very large, much of it took the form of equity, loans and guarantees rather than additional spending or tax cuts.

The NextGen EU funding that will begin to be disbursed in 2021 is novel in its funding through debt, its allocation of large grants to member states and its size – 209 bn euro in the case of Italy. But, given Europe’s gloomy outlook for 2021 and the track record of the last two decades, it is not enough.

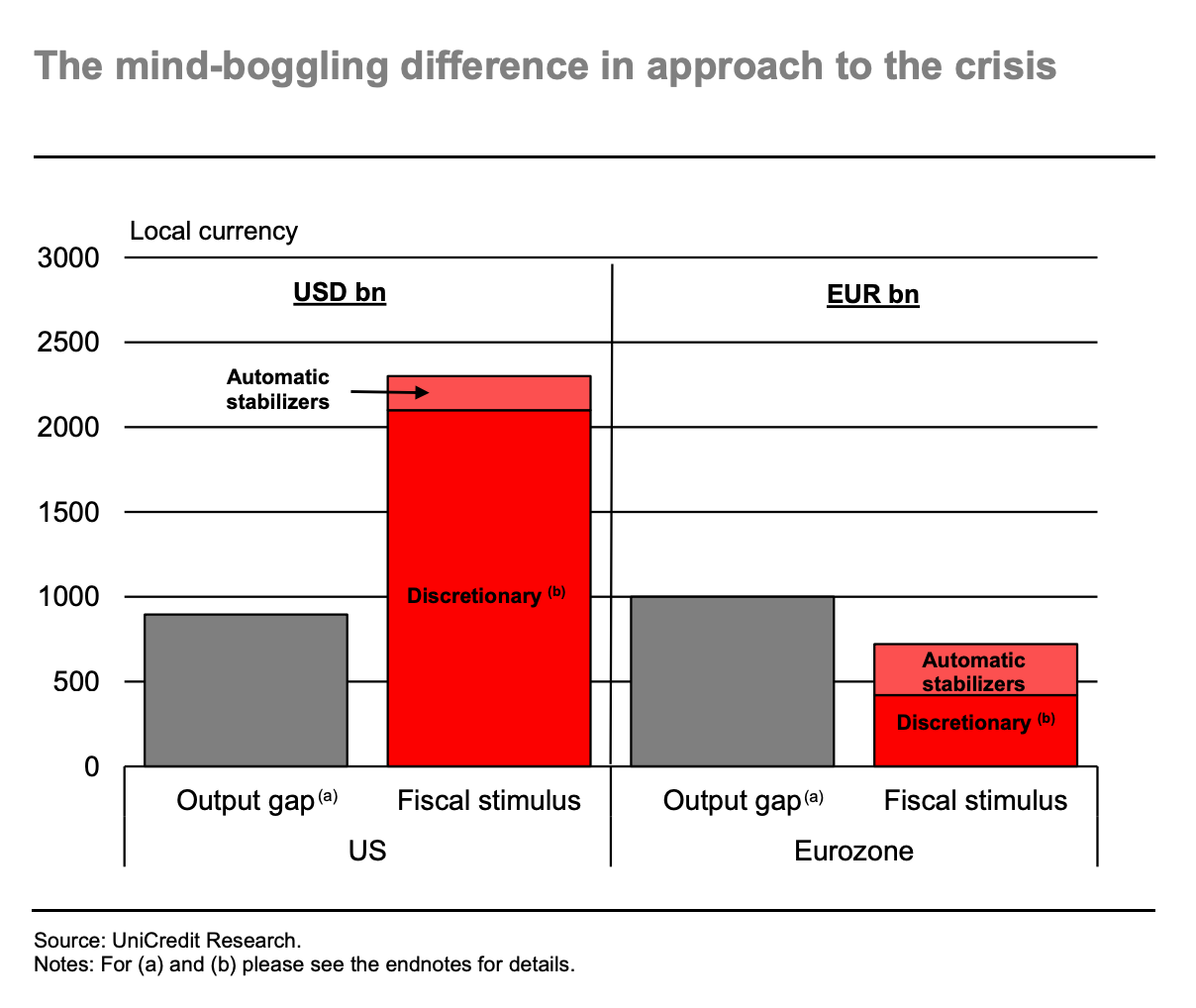

In 2020 the collective EU deficit surged from 0.6% to 8.8% of GDP. The ECB now projects that the deficit will tighten to 6.4% of GDP in 2021. In part that is due to economic recovery, which automatically increases revenues, but it also has to do with the slowing of life support and stimulus spending. This contrasts with the US.

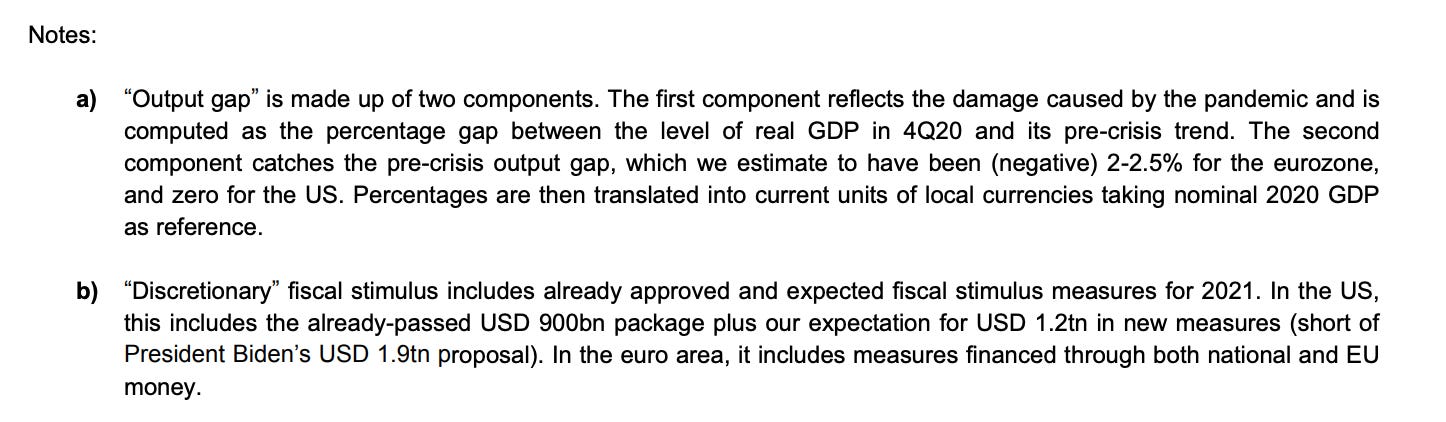

Earlier in February, Erik Fossing Nielsen of Unicredit produced a dramatic comparison of the US and EU stimulus programs highlighting the gap between them in 2021.

Source: Unicredit

I used my Social Europe column of a few weeks ago to argue for a bigger fiscal and monetary effort. See Chartbook Newsletter #12

I’m delighted to see that the FT editorial board has come out in favor of the same view.

The immediate challenge is to find the best way to spend the money that is already allocated. As the FT and before them Jean Pisani-Ferry pointed out, it is, indeed, crucial that Italy find ways to productively employ the large funding allocated to it. If it fails to do so, it will cast a shadow over any future fiscal project going forward.

Beyond that, the question is how the EU ensure that its member states are in a position to continue to deliver the fiscal support they need to speed up recovery and boost the laggards onto a higher growth path.

Currently, the pre-crisis budget rules are suspended until the end of 2021. For them to be reimposed, given current deficit and debt levels, would be a recipe for disaster. The rules were already up for debate as 2020 began. See this January 2020 IMF conference.

The debate over how to reshape the EU’s fiscal framework will continue with ever greater intensity in 2021. Olivier Blanchard, Álvaro Leandro, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer have issued a PIIE paper on the topic.

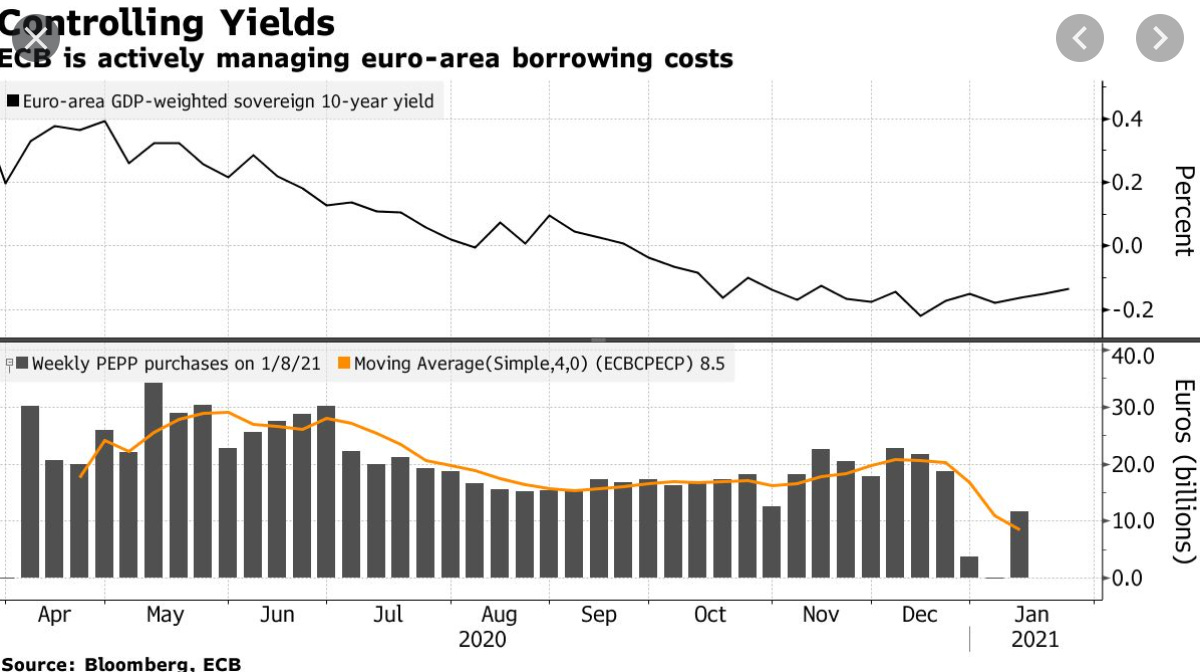

The reason that we have time to reflect, the reason that the debate is not driven by panic, as it was between 2010 and 2012 is that the ECB is stabilizing the bond market. ECB bond purchases are pinning Eurozone interest rates at record low levels. Without saying so explicitly the ECB is effectively managing yields.

But is the ECB doing enough?

Given what the ECB has done, it may seem like a ludicrous question. But the ultimate test are the impact of central bank policy on financial markets and the real economy. And the impact of policy in one area depends on the stance of policy in the rest of the world.

Under Mario Draghi in 2107, the ECB’s asset purchases were large enough, given the stance of other central banks at the time, to drive money out of the Euro Area in search of better yields in the US and elsewhere. This is a desirable effect of a QE policy, helping to push the exchange rate down. In 2020 despite the scale of the ECB’s bond buying we have seen no such effect.

Source: Robin Brooks IIF

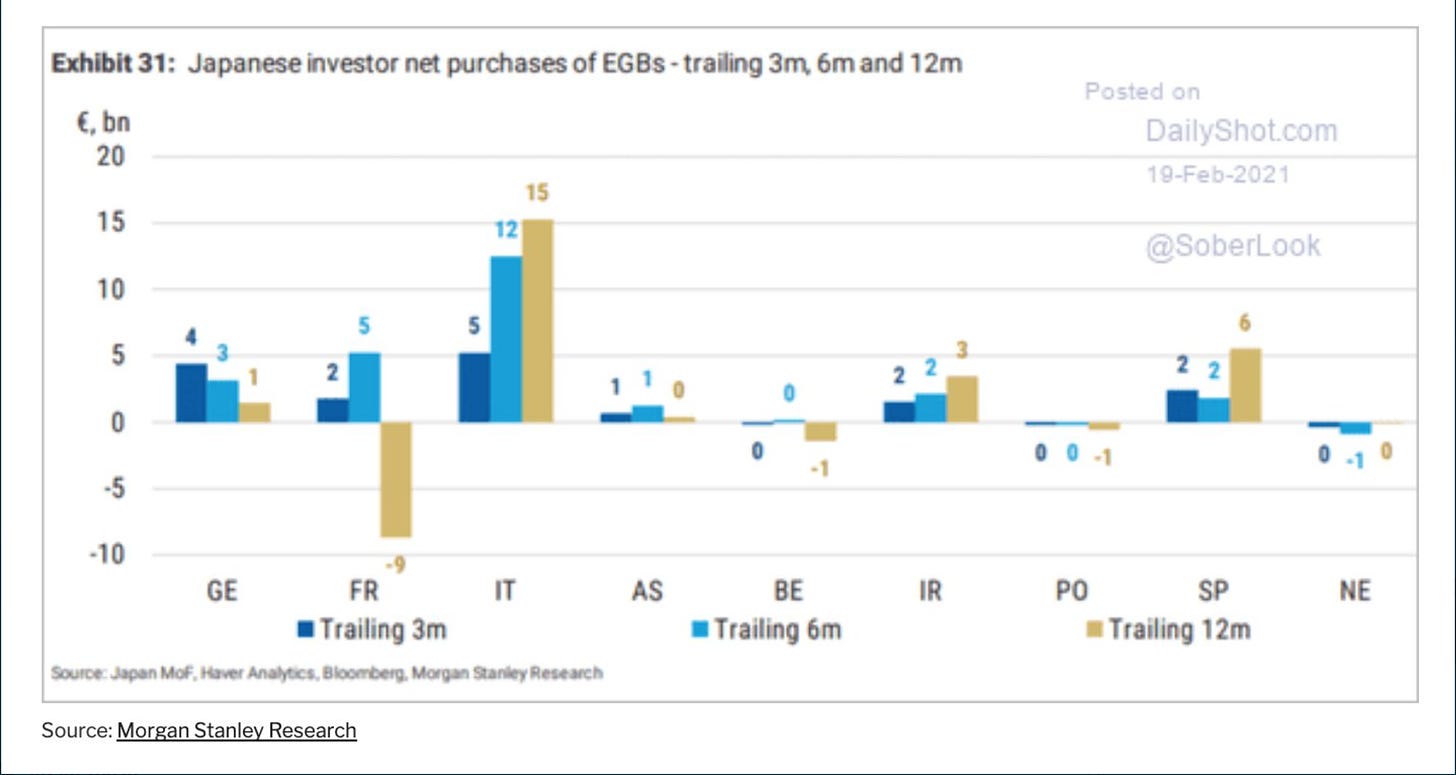

Foreign funds have, in fact, flowed into the Euro area. The Euro has strengthened v. the dollar. This is evidence of confidence in the robustness of higher yield Euro zone bonds but it also suggests that given the conditions in Europe, the ECB could be doing even more to push yields down.

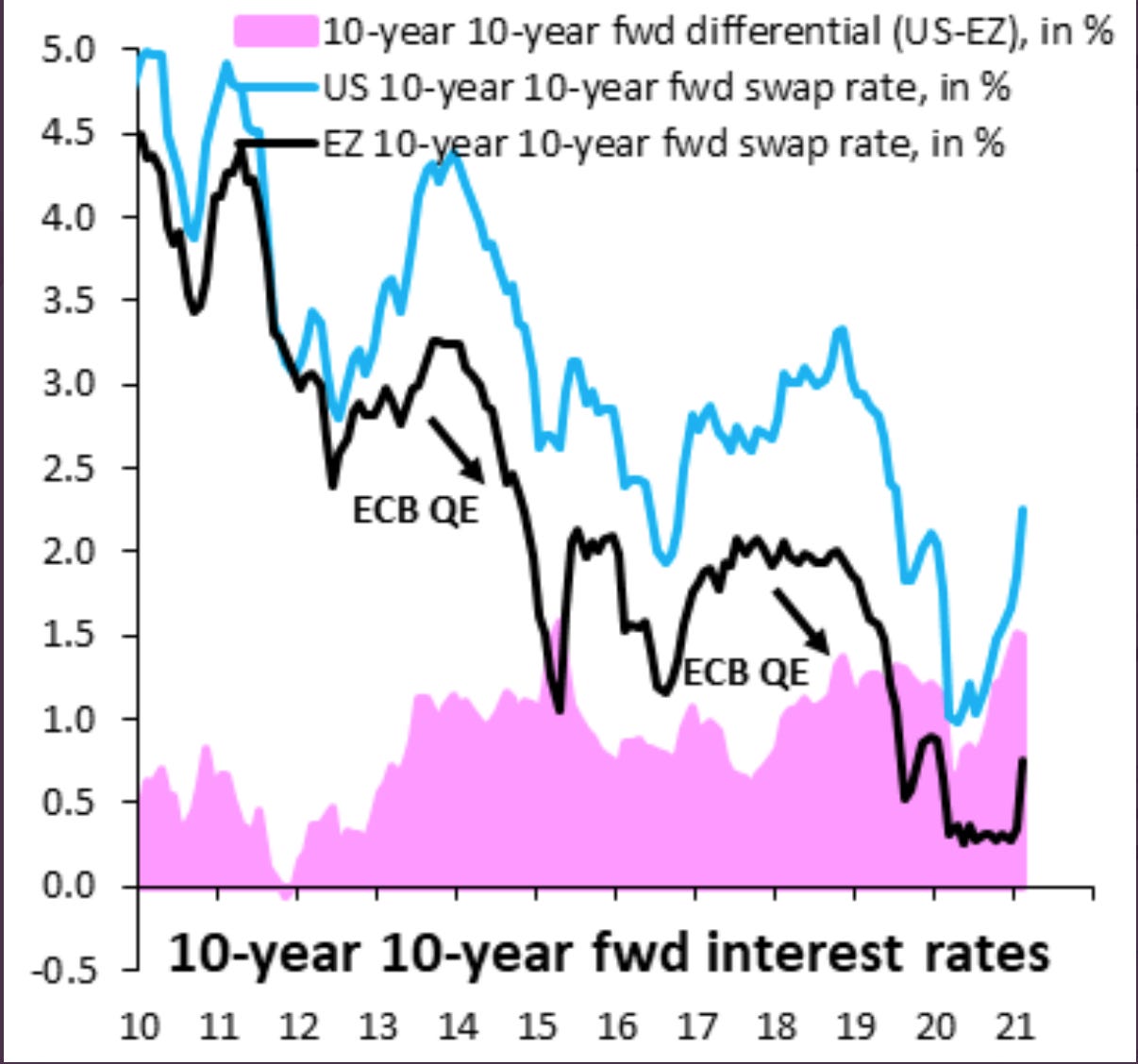

Source: Morgan Stanley via DailyShot

There is all the more reason to act if, as has begun to happen in recent days, the upward movement in interest rates in the US begins to trigger an upward movement on the other side of the Atlantic too.

Source: Robin Brooks, IIF

It is all very well for rates in the US to be nudging upwards. Markets are anticipating an accelerating recovery and absolutely massive fiscal stimulus in 2021. But that is the last thing that the EU needs.

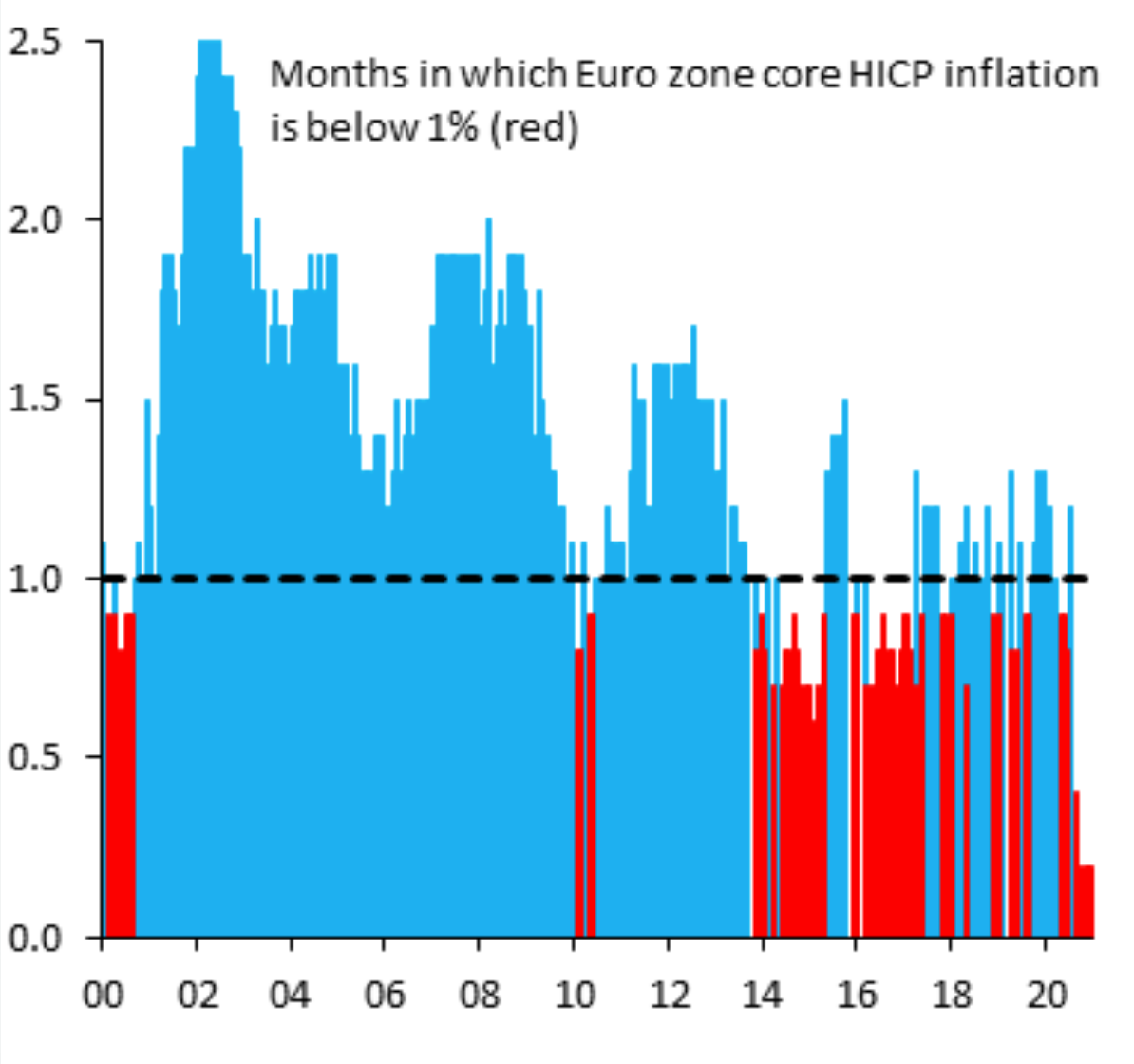

As Robin Brooks puts it: “The ECB’s done great things since 2014: negative rates, QE & PEPP. But it hasn’t done enough. Core inflation continues to grind lower, so – relative to the scale of the deflation problem – stimulus just hasn’t been aggressive or proactive enough.”

PS and yes, if you don’t already, you should follow Robin Brooks and Erik Fossing Nielsen and Francois Ducrozet and Jean Pisani-Ferry they are essential reading.