Reminder – Conley & Silvers Zoom lecture, Monday 14 December 8 pm New York Time.

Quick reminder. For those of you who enjoy zoom talks, every month I share some ideas on the state of the world economy and politics with client’s of Conley & Silvers, my wife’s boutique educational travel company.

To join my talk on Monday 14 December use the complimentary code GETAWAY at checkout. Go to the Conley & Silvers website, then find my next talk on the calendar (14th of December), click on that talk and book your slot.

On Monday I am going to do a “three hubs” – EU, US, China – review of where we stand at the end of 2020.

Reading China’s State Capitalism

There is no more important issue right now than how to read China’s state capitalism and its likely trajectory.

In Chartbook Newsletter # 8 I collected some material on China’s recent economic development. In # 9 I want to dig a little deeper, on the lines along which China’s political economy is interpreted. I offer these thoughts as a general reader of political economy rather than a China specialist.

The basic question seems to be:

Are we seeing a power grab by Xi that will lead to an overgrowth of state-owned businesses and the strangulation of China’s private sector? Or, are we seeing the emergence of a new streamlined form of state capitalism?

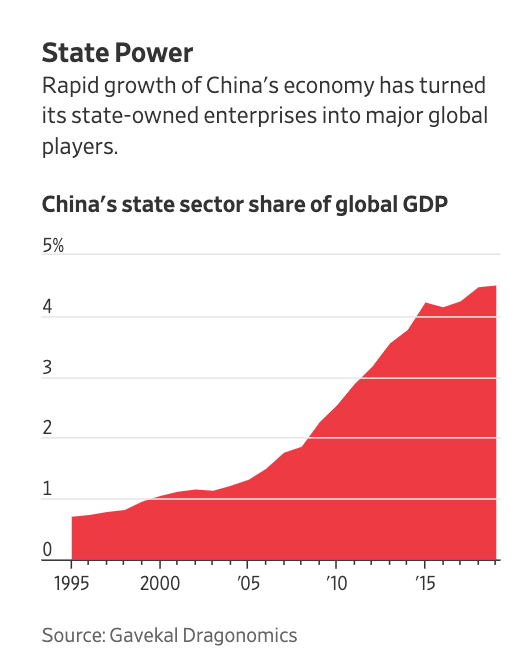

It is a crucial question for China. It is a crucial question for the world economy. By one estimate, China’s State-Owned Enterprises account for a larger share of global GDP than Japan.

But the trajectory of China’s state capitalism also has broader historical implications: Should we expect liberalism’s preconceptions about the logic of economic development to be confirmed in China, or not?

Dual Circulation

Faced with the Trump administration’s onslaught against the Chinese tech sector this year, the key theme of recent pronouncements on Chinese economic policy has been “dual circulation”. The idea is that China’s economic future will be shaped not on a flat vision of seamless integration with the West, but on two distinct circuits: one domestic, the other globally orientated.

As James Crabtree notes in an excellent long read for Noema Magazine, this marks a distinct shift in China’s outlook on globalization. It marks end to any aspiration of one world economic integration, if that, in fact, ever had any real relevance it is now buried.

And the illustration by Claire Wilson that I’ve featured at the top of this newsletter is fantastic too!

Kudos to Noema for commissioning great graphic work like this.

Bringing the Party back

Lurking in the background of debates about One Belt One Road or “Dual Circulation”, are a broader set of issues about the trajectory of China’s political economy.

In the pages of the WSJ, Lingling Wei has a big piece highlighting the ever greater control of the party over China’s economy.

Through a series of cameos she shows how even large private enterprises are falling under sway of the party. Party committees intervene in the running of business at all levels.

Lingling Wei notes a continuous shift within the Chinese elite away from those favoring “opening up” or market reform. She cites the case of Xu Zhong who until last year “was head of the research department of China’s central bank. He publicly blamed China’s poor governance and market distortions on the state’s hand in allocating credit, which had caused private firms to be deprived of financing. “The first institutional problem that leads to financial chaos is unclear boundaries between government and the market,” he wrote in an article published in December 2017. In a high-level economic forum in February 2019, he called for accountability of the government when it came to market reforms. Shortly after that, he was moved to a new role outside the central bank in an association of market dealers. “The market-reform camp is all but gone,” says an economist who advises the government. “By now, it’s pretty clear what kind of reform the top guy really wants.””

For Lingling Wei this shift has a history that goes back to 2015:

“Initially, Mr. Xi had been open to advancing market reforms that began in China under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s. In late 2013, Mr. Xi’s leadership vowed to give market forces a “decisive role.” He blessed market-minded regulators who talked up stock investing and relaxed government control over China’s currency. His administration even pondered a proposal to have professional managers rather than party apparatchiks run state companies.

One after another, those reform plans led to chaos. In the summer of 2015, a big stock-market selloff pounded markets and embarrassed Mr. Xi. The central bank’s move to set the Chinese yuan freer spooked the public further.

In closed-door meetings with underlings, Mr. Xi made his displeasure clear, according to the officials close to the leadership, and unleashed state forces to fix what he saw as the market’s woes.

Senior state-sector officials successfully lobbied Mr. Xi’s leadership to scratch plans to bring more market-oriented managers to state companies.”

For earlier reports by Lingling Wei on 2015 see this from 2015 and this from 2017.

Macroeconomic Frame

Picking up on the significance of Lingling Wei’s piece, Michael Pettis chimed in on twitter to remind us of his excellent FT piece from back in the spring, in which he offered an alternative explanation of the “return” of state-driven economic growth in China.

The issue for Pettis is less politics than the perverse logic of China’s macroeconomic governance:

“ Mainstream economists have long called for Beijing to improve China’s market mechanisms, and they have deplored the rolling back of the private sector over the past decade. But despite years of supply-side proposals and repeated reform pledges, there has been little evidence of a substantial reversal in the trend towards greater government control of the economy. This shouldn’t surprise anyone. Over the long term, Chinese growth might indeed benefit from a stronger private sector and a more market-oriented economy. Yet in the near and medium term, this approach will do almost nothing to address either the real causes of China’s slowdown or its growing reliance on debt. Nor would it diminish Covid-19’s economic effects. This is because China doesn’t have a supply-side problem. It has a demand-side problem, which the coronavirus pandemic has only made worse. What is more, the rolling back of the private sector in recent years is a consequence, not a cause, of China’s underlying demand-side problem.”

If you aim for higher growth rates than an economy with repressed household consumption can deliver, you can only achieve that growth by constantly raising the share of demand that comes from state-driven investment and infrastructure construction. The growth target combined with a warped, inequality-enhancing political economy, make any efforts at institutional change irrelevant.

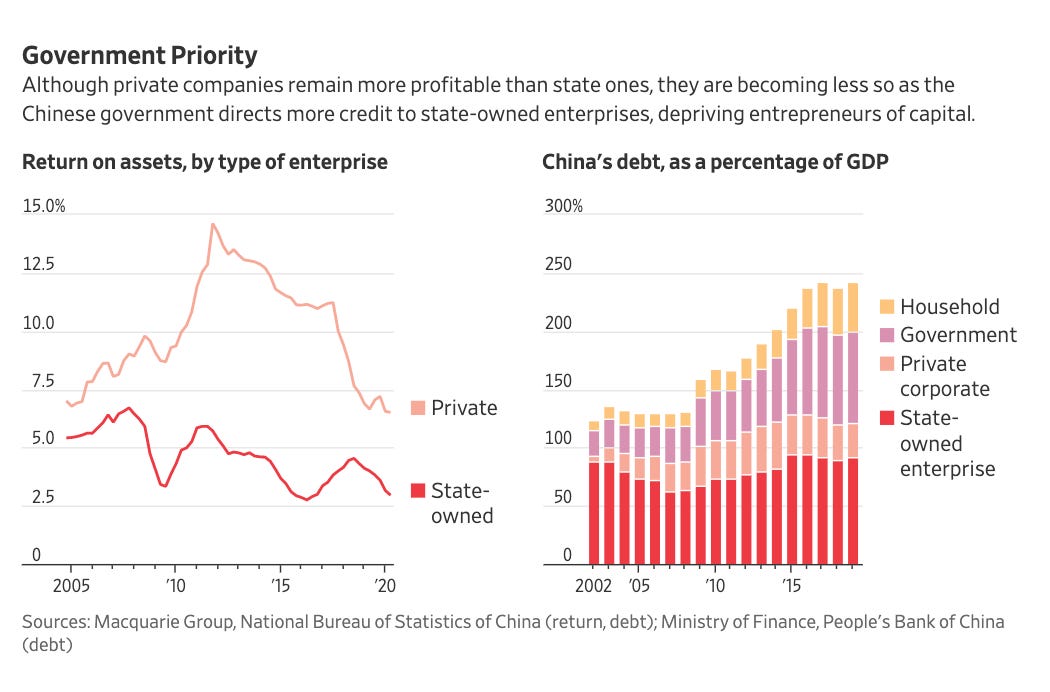

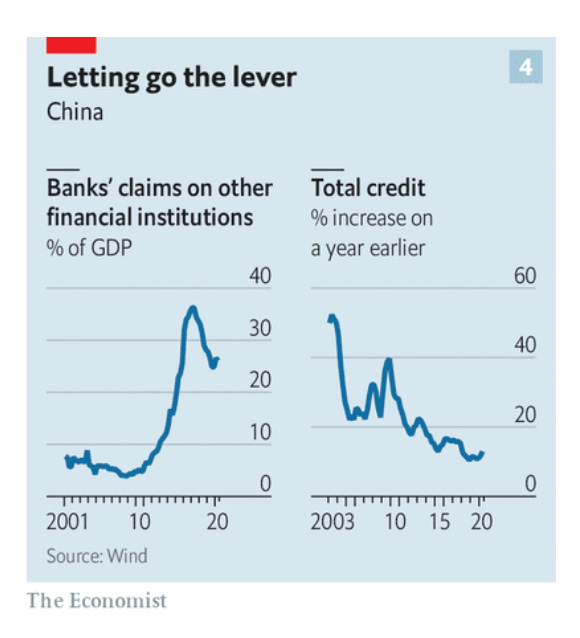

The upshot, for Pettis as for Lingling Wei, is a declining trend in productivity, falling rate of return and an unsustainable build-up of debt.

Is this inevitable?

Reinventing State Capitalism

There is in Western commentary about China an element of wishful thinking. There is a profound skepticism amongst liberals about the viability of long-run growth on the lines that the CCP has been pursuing. The one-man authoritarianism of Xi has reinforced this conviction. In the end, China’s hybrid political economy must surely run out of steam and succumb to its contradictions. Alarmingly, in the last few years, the aggression of the Trump administration towards China was rationalized, insofar as it was rationalized, by the daredevil hypothesis that Xi’s regime was fragile and it was time to strike.

That view echoed down to 2020 in the widespread expectation that corona would be Xi’s “Chernobyl moment”.

At this point that seems rather implausible. The regime’s response has been, to say the least, vigorous. Economic growth has returned to China ahead of any other major economy. Financial risks are real, but are being actively managed. Nor has China shrunk from taking measures even against its most mighty tech oligarchs. In November Beijing halted what would have been the largest IPO in the world, valuing Ant financial on a par with JP Morgan. It was stopped at the last moment and followed by tough new rules on tech competition designed to curb oligopolistic tendencies. Perhaps, state capitalism rather than reaching its limit, is being reformed to give it more order, longevity and even dynamism.

It is an argument that turns liberal assumptions about economic history on their head. It opens a vista on the next decades, which is radical in the sense of being open-ended. It challenges us to imagine that liberal logics will not work out the way we might expect. What if China is making history, not simply playing out its end?

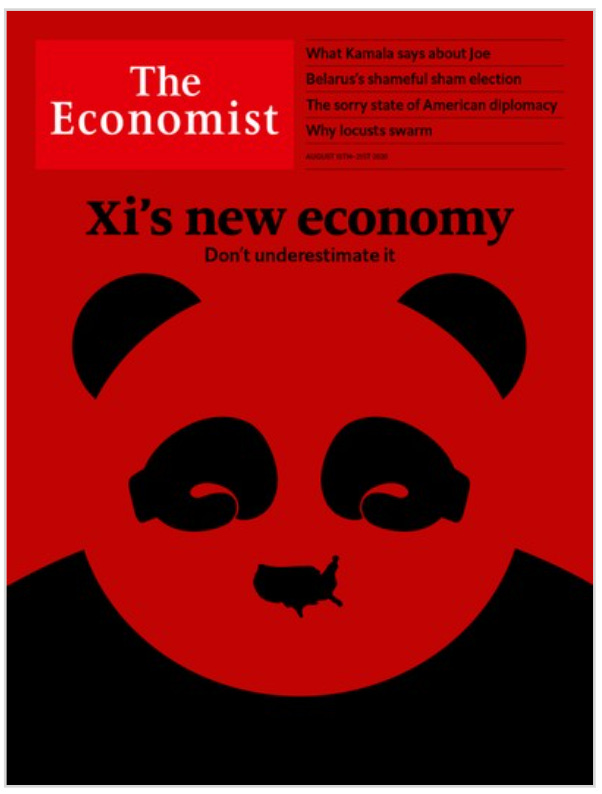

On grounds of interpretive principle, I find this take far more compelling than the standard liberal declinism. I find the “dynamic state capitalism” thesis all the more fascinating, because one of its most articulate proponents is The Economist magazine. One can accuse the Economist of many things, but as our friend Alex Zevin showed in his brilliant history of the magazine, it does not shirk when it comes to fighting the liberal corner in the war of historical ideas.

Xi’s New Economy

The leader and brief in the August 13th 2020 edition offer a powerful interpretation of China’s current trajectory that runs directly counter to liberal commonsense.

Economist pieces are not attributed, but I am reliably informed that the analysis is the work of Simon Rabinovitch.

The basic elements of the Economist’s “dynamic state capitalism” thesis are:

Contrary to Lingling Wei’s view, Xi has not changed his line. He inherited what was a highly unstable structure, which he has restructured since 2013 in pursuit of greater stability.

As the Economist puts it: “Mr Xi announced his agenda in 2013, vowing that China would “let the market play the decisive role in allocating resources”, while reinforcing “the leading role of the state-owned sector”. When domestic stocks crashed in 2015 the government’s focus shifted … But the party now thinks it has won this “battle against financial risks” and is getting Mr Xi’s agenda back on track in a new, bolder form.”

The instability of the previous system was in part due to its dualism: a lopsided marriage of a slow-moving state sector and a hyper dynamic private sector.

The project of stabilization involves:

Taming the credit-fueled dynamo ,whose risks revealed themselves in 2015.

Disciplining the oligarchs who were principal beneficiaries of credit-fueled growth. Cracking down on external capital flows was not just a macroeconomic measure. The haphazard purchase of prestigious Western assets by obscure Chinese firms was, in fact, a disguised forms of capital flight. Oligarchs feathering overseas boltholes.

Again China may be learning lessons on how not to do it from Russia’s recent history. In China, billionaires know that they must tread carefully or risk finding themselves behind bars.

But, a society as complex as modern China cannot be ruled on that kind of arbitrary basis. So, another major plank of Xi’s new regime is the use of rule of law for regulating lesser conflicts, even those between private interests and the state.

As a recent party statement put it: “”The more complicated the international and domestic environment, the more it is necessary to use rule-of-law thinking.” Governance capabilities must be enhanced to “ensure the long-term stability of the party and the country.”“

“Xi made the remarks at a meeting of the party’s Central Committee on the rule of law, which was held in Beijing on Nov. 16-17, with the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s top decision-making body, all attending.” As Nikkei Asian Review notes, the Chinese version of a recent Xinhua report of a key party meeting uses the word “rule of law” 114 times.

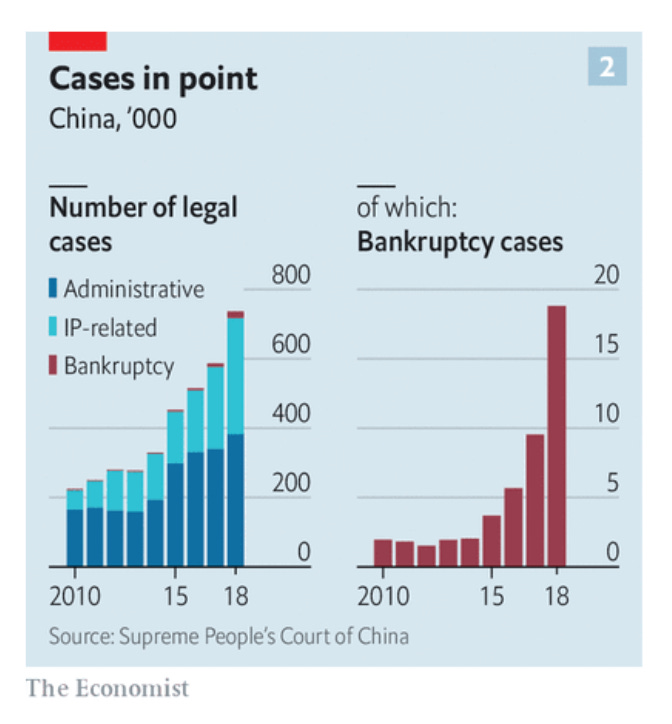

The “rule of law” is not mere window-dressing, but a functional necessity and it shows up both in Xi’s speeches and in a huge surge in activity of the courts in China.

As the Economist notes: The legal system “is a tool of oppression, as its extension into Hong Kong is making clearer than ever. Mr Xi has been relentless in targeting anyone standing up for human rights. Yet he has also overseen a partial professionalisation of the judicial system and given courts more authority on non-political matters. The economy is simply too complex, and corruption too prevalent, to rely on local officials to adjudicate disputes as they used to.

These changes to the courts have coincided with an explosion in cases. Administrative lawsuits, which typically involve people suing the government, have more than doubled since 2012, the year that Mr Xi became China’s paramount leader (see chart 2). Bankruptcy filings are up ten-fold. Last year Chinese courts accepted more than 480,000 intellectual property cases, nearly five times as many as they did in 2012, with some going to a new national court devoted to the area. Foreign plaintiffs won 89% of all patent infringement cases, according to Rouse, a consultancy.”

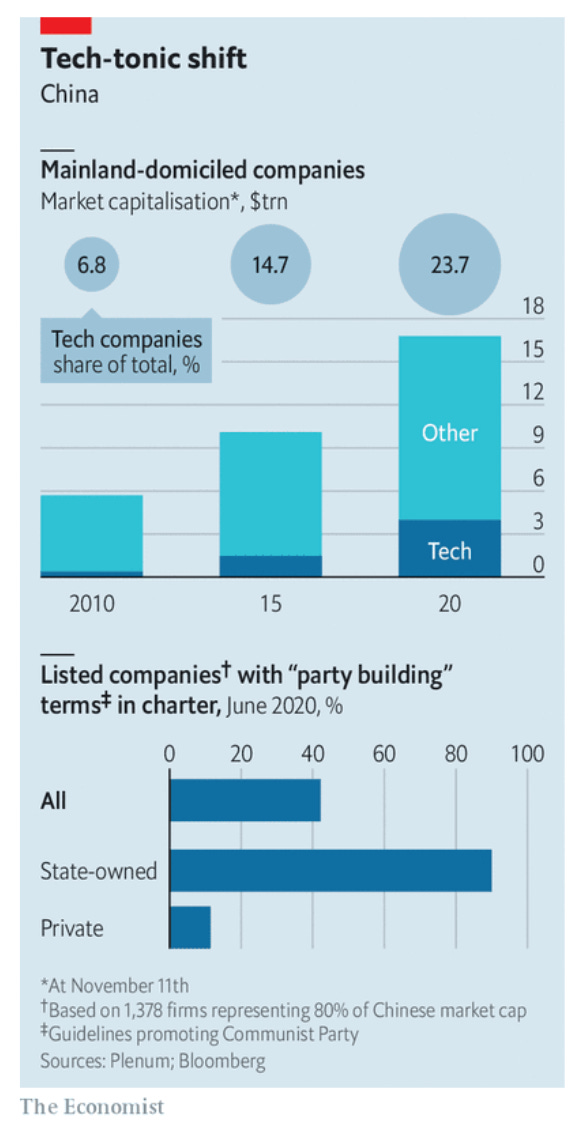

On top of derisking the financial system, curbing the oligarchs and regularizing the use of law, the fourth element of stabilization is overcoming the gulf between the realm of the state-party-economy and private business by fusing them together.

The aim is not to create a mass of stagnant state-owned monopolists, but to inject new dynamism into the economy as a whole. As the Economist puts it: “The idea is for state-owned companies to get more market discipline and private enterprises to get more party discipline, the better to achieve China’s great collective mission.”

With that in mind, the regime is pushing governance reform in SOE, which, at least, in some firms is having an effect. Again the Economist credits Xi with striking a prudent balance:

“Mr Xi has made clear that he does not favour a fundamental overhaul for soes. There will be nothing like the wave of closures and privatisations implemented in the 1990s, a cull that carried a steep social price in unemployment but also helped to clear the way for buccaneering entrepreneurs. But it is a mistake to view the situation as static. The state is trying both to get more out of soes and to use them to get more out of the private sector.”

One place to watch, to gauge the success of this balancing act is the stock market where well-informed locals make clear distinctions within the SOE sector. The Economist notes that the “China Merchants Bank trades at 1.5-times book value, compared with just 0.5-times for Bank of Communications.”

The regime “wants more state firms to attract private-sector investors and private firms to find state-owned partners. Cross-pollination along these lines has happened before (notably, when major soes listed on stock exchanges in the early 2000s). But this time it will tie together a wider array of companies, notes Chen Long of Plenum, a research firm. In the past few years, state firms have pulled in more than 1trn yuan ($145bn) of private capital. And in the first half of 2020 nearly 50 private-sector enterprises listed in China attracted chunky investments from state firms.”

And contrary to liberal preconceptions the results are not necessarily disastrous. As The Economist notes: “Zhang Xiaoqian, an economist at Zhejiang University, has found that both soes and private firms increase their spending on research and development after being remade as mixed-ownership firms. State firms benefit from an injection of ideas and risk appetite. Private firms benefit from better state connections which make it easier to raise capital.”

Top down industrial policy is, of course, the familiar mode of Chinese intervention. But, as The Economist notes, it actually has a checkered track record. All too often it is scatter shot. And this was true for Made in China 2025 as well.

But, in a dialectical twist, the fact that observers in the West are threatened by Chinese policy has in recent years provoked a dramatic reaction. China now finds itself in a bona fide tech war with the West. And that has actually served to give real clarity to the directions in which Beijing must act.

Through the reaction that it provokes in others, the vision of a coherent Chinese state capitalism may actually be taking on a new reality.

All in all the message from the Economist is clear. Underestimate China at your peril.

“Mr Xi is not simply inflating the state at the expense of the private sector. Rather, he is presiding over what he hopes will be the creation of a more muscular form of state capitalism.

It is getting harder to distinguish between the state and private sectors. It is getting harder to distinguish between corporate and national interests. And for all its inefficiencies, contradictions and authoritarianism, not to mention its increasingly pious cult of personality, it is getting harder to claim that state capitalism will hobble China’s attempts to produce companies and master technologies that put it on the world economy’s leading edge.

It isn’t Milton Friedman, but this ruthless mix of autocracy, technology and dynamism could propel growth for years.”

The leader in the August 13 edition draws the conclusion:

“One thing is clear: the hope for confrontation followed by capitulation is misguided. America and its allies must prepare for a far longer contest between open societies and China’s state capitalism. Containment won’t work: unlike the Soviet Union, China’s huge economy is sophisticated and integrated with the rest of the world. Instead the West needs to build up its diplomatic capacity (see article) and create new, stable rules that allow co-operation with China in some areas, such as fighting climate change and pandemics, and commerce to continue alongside stronger protections for human rights and national security. The strength of China’s $14trn state-capitalist economy cannot be wished away. Time to shed that illusion.”