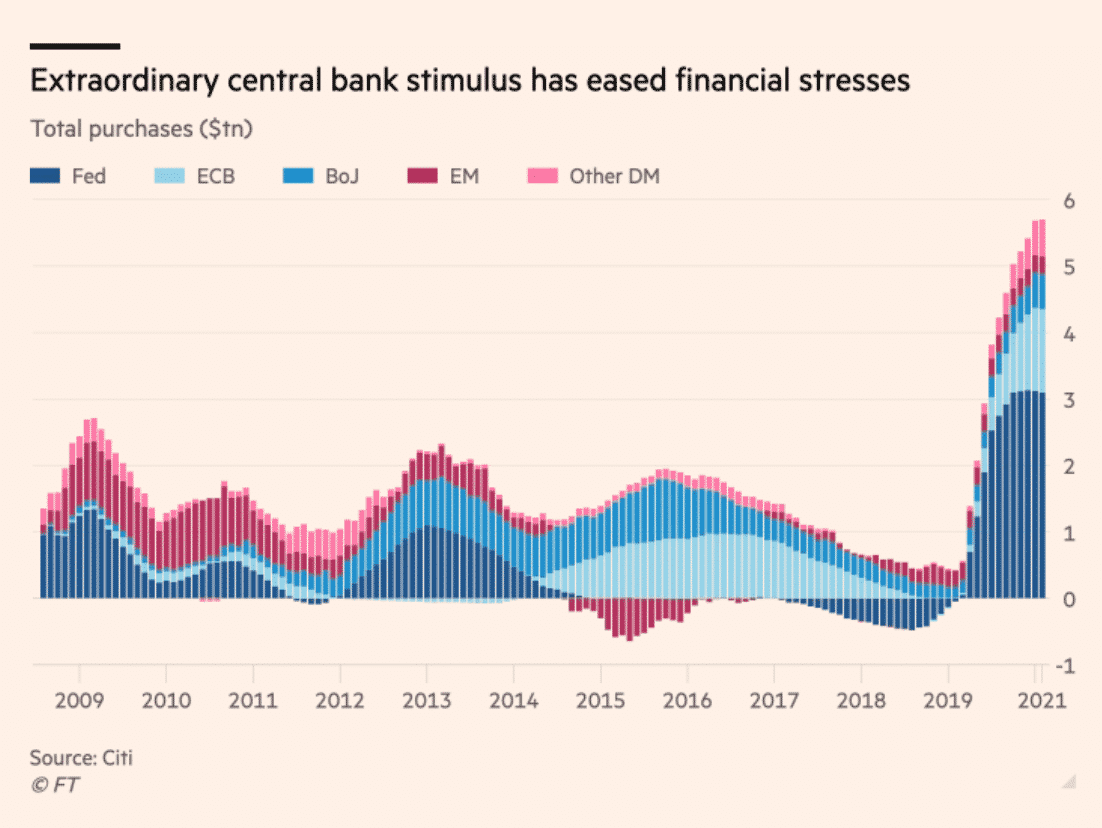

The scale, pace and extent of central bank action in response to the COVID-19 crisis has been spectacular. It dwarfs that which followed the financial crisis of 2008.

In this piece in the Guardian, I sketched a first analysis of action on the part of the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of England. My aim was simply to establish a chronology of the action.

This is no more than the beginning of a comprehensive investigation. That would involve a deeper analysis of the actual dynamics of crisis in the financial markets, which will be for another post.

We would also like to know more about the key decision-makers at the central banks.

The expansion of the programs is beginning to raise serious issues about conflicts of interest. We are exiting the phase of awed amazement at the scale of the actions taken. A more critical evaluation will soon begin.

This post is a collection of materials that expands upon the simple chronology I laid out in the Guardian piece.

For sheer analytical clarity this excellent piece by Craig Torres comes top of my list. He breaks down the Fed’s nine new programs launched since the beginning of the crisis into three groups:

Lender of Last Resort: Commercial Paper Funding Facility and the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility the Primary Dealer Credit Facility and the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility –

Fiscal Partner: Programs in which the Fed is acting as an extended arm of Congressional stimulus policy – the Main Street lending program, which will buy up to $600 billion in loans from banks. Municipal Liquidity Facility. Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility

Investor of Last Resort: “the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility, will buy debt or loans directly from corporations. The other — named the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility — will buy corporate debt in secondary markets, including exchange-traded funds that specialize in high-risk, high-yield debt.”

This is a typology which one can easily see having wide application.

At Politico a team of reporters assembled their own narrative review of the crisis-fighting in March. It is particularly illuminating concerning the officials around Treasury Secretary Mnuchin.

The Bloomberg reporters Jana Randow and PIotr Skolimowski are doing a great job covering the ECB. This is an excellent piece on the events in Frankfurt in mid March. They confirmed the bombshell that Lagarde’s gaffe on 12 March was not unmotivated. The crucial line about spreads not being the business of the ECB appears to have been fed to Lagarde directly by Isabel Schnabel.

The muffled rumbles of dissent within the ECB can be read off this official account of the meeting on the evening of 18 March.

What is becoming clear is that apart from Lagarde herself a key role in the formulation of the ECB’s policy response is being played by Chief Economist Philip Lane formerly of the Central Bank of Ireland and Lagarde’s advisor the macroeconomist Roland Straub. who was appointed to that role by Mario Draghi, and Massimo Rostagno the director of monetary policy.

Unsurprisingly, Jerome Powell and the Fed are attracting a lot of attention. Unlike Bernanke and Yellen, Powell is no super-wonk. Unlike his predecessors, Powell does not offer academic observers of the Fed a point of personal identification. But he has, nevertheless, hurled the institution into a feverish bout of activism.

Neil Irwin at the New York Times has a profile which argues that it is precisely Powell’s lack of doctrinal commitments and varied business career that has enabled his remarkable activism.

Gilliant Tett of the FT also points to the fact that Powell “forged most of his career in the camera-shy world of corporate law. Colleagues described him as “pragmatic”, “self-effacing”, “genial”, “humble” and “cautious”. However, Mr Powell is fast becoming the least cautious — or dull — Fed chair in history.” She ascribes his freedom of action to his close working relationship with Mnuchin at Treasury, Powell’s assiduous cultivation of Congress and the fact that Trump is preoccupied with turning COVID-19 into a daily electoral campaign. Tett also remarks that the sheer scale of the Fed’s intervention gives us an alarming indication of how serious it thinks the risks to the American economy are.

Richard Clarida (Fed Vice Chair), Jerome Powell, John Williams (NY Fed)

As is highlighted in an excellent profile by Nick Timiraos of the WSJ, Powell works with a close team of advisors. One is Vice Chair Richard Clarida, a monetary economist who until 2018 worked for the giant bond house PIMCO.

“Messrs. Clarida and Powell, both mild-mannered professionals who formed the nucleus of the Fed’s leadership team, had built a strong relationship during their first year working together and cultivated the respect of the Fed’s staff. At the central bank’s holiday party last December inside the marble atrium, Mr. Clarida sang “What the World Needs Now Is Love” with Mr. Powell playing guitar.”

Another key figure is Lorie Logan

“Lorie Logan, the manager of the Fed’s portfolio. Ms. Logan, a 21-year veteran of the bank, had been at the New York Fed on Sept. 11, 2001. When the World Trade Center towers collapsed a few blocks from the New York Fed’s fortresslike headquarters, she led a few colleagues to check on the markets, working upstairs while others hunkered down in the basement.”

Logan’s Fed biography is here.

Logan moved into her new role in December 2019. Her elevation followed a year of turmoil at the New York Fed after John Williams “ousted” Simon Potter who had previously been responsible for financial markets. The Fed faced a surge of turbulence in repo markets and questions were asked about the leadership. None of that hesitancy has remained in 2020.

Now at the PIIE, Simon Potter wrote a striking account of the sheer scale of Fed asset purchases. It has broken all records for central bank intervention.

In Dissent magazine historian Trevor Jackson offers a dramatic assessment of the Fed’s role. He remarks: “In terms of crisis governance, the United States is not a country with a central bank; it is a central bank with a country.”

Its a great line. But I cant help wondering whether it captures the dynamic of our current moment. The Fed’s degree of agency is undoubtedly dramatic. But what is sucking it into new engagements are the ramifying shocks to the American economy . Furthermore, by the third week of March it was clear that the Fed could no longer act alone. It needed to work in close conjunction with Treasury and Congress. That may turn out to be the more distinctive feature of this crisis.