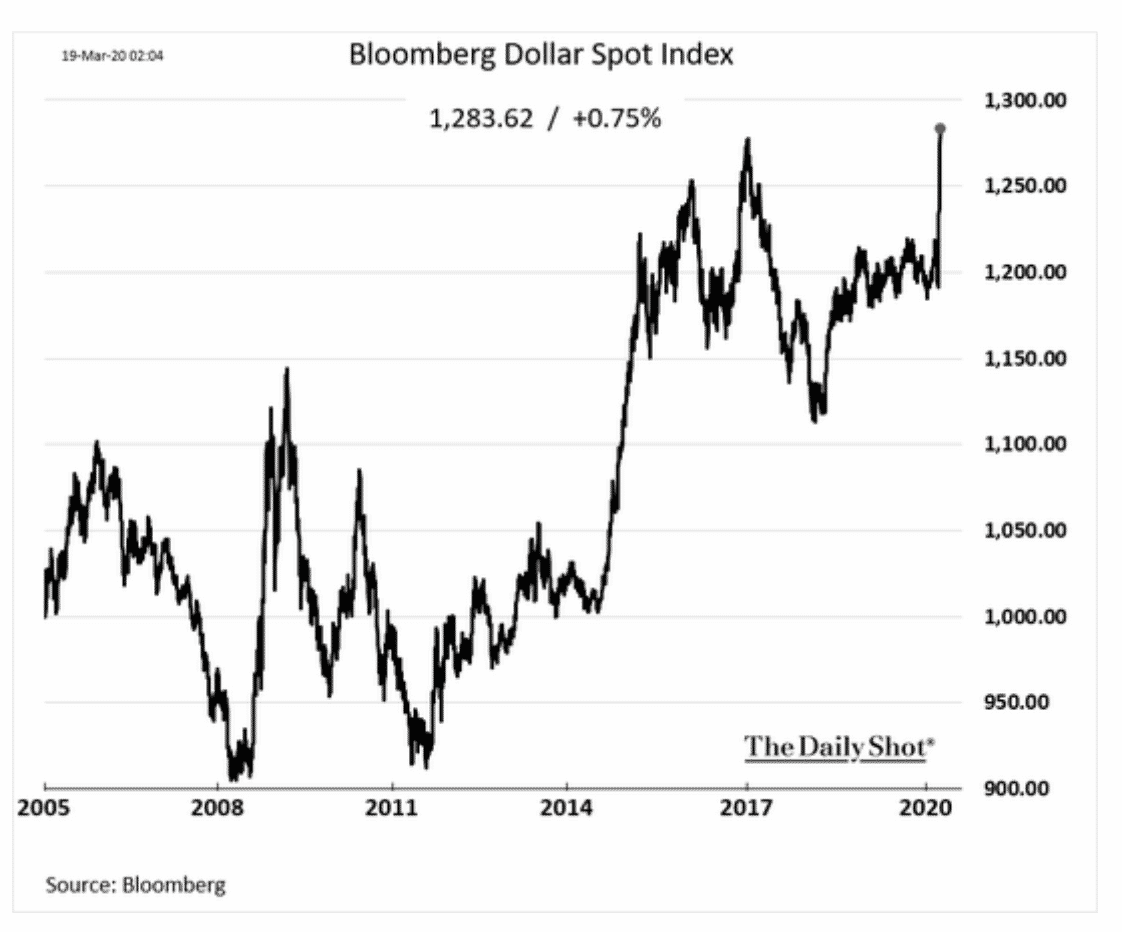

In the last two weeks, as the financial markets have reacted to the corona shutdowns, one of the most alarming features of the panic has been a rush into cash dollars or the closest possible substitutes, which are ultra-short-term Treasury bills. As demand shot up, their yields have crashed.

In the US itself this has shaken the markets. Everything has sold off – shares, corporate bonds, even gold. Globally, this has produced a huge shock to stock markets, bonds, both sovereign and corporate and a lurching devaluation of all currencies against the dollar.

This would be disruptive enough in any case, but it is particularly alarming given that the world financial system is based on dollars and many banks, financial institutions and non-financial corporations around the world rely heavily on borrowing dollars to fund their operations. To cover at least some of the risk of being short dollars they hedge against exchange rate fluctuations. As dollar funding dries up, as there is a run into dollars and the dollar appreciates, large parts of the world economy face dramatically increased funding costs, exchange losses and increased costs of hedging or swapping other currencies into dollars.

This would be disruptive enough in any case, but it is particularly alarming given that the world financial system is based on dollars and many banks, financial institutions and non-financial corporations around the world rely heavily on borrowing dollars to fund their operations. To cover at least some of the risk of being short dollars they hedge against exchange rate fluctuations. As dollar funding dries up, as there is a run into dollars and the dollar appreciates, large parts of the world economy face dramatically increased funding costs, exchange losses and increased costs of hedging or swapping other currencies into dollars.

In understanding the problem of global financial dependence on the dollar we all follow in the footsteps of the brilliant analysts at the BIS now led by Hyun Song Shin.

Brad Setser and collaborators have added key insights into private sector balance-sheets in Asia.

Once set in motion, the risk is that this becomes self-sustaining, further escalating the run into dollars. The problem first became acute in the week beginning Monday 9th March. Last week the dollar shortage tightened. On Wednesday 18th March the forex markets were in panic mode.

The major center of forex trading worldwide is the City of London. As rumors circulated that the Johnson government was finally going to shut London down, markets came close to collapse. In a market with daily turnover running into the trillions there were no buyers for anything other than dollars.

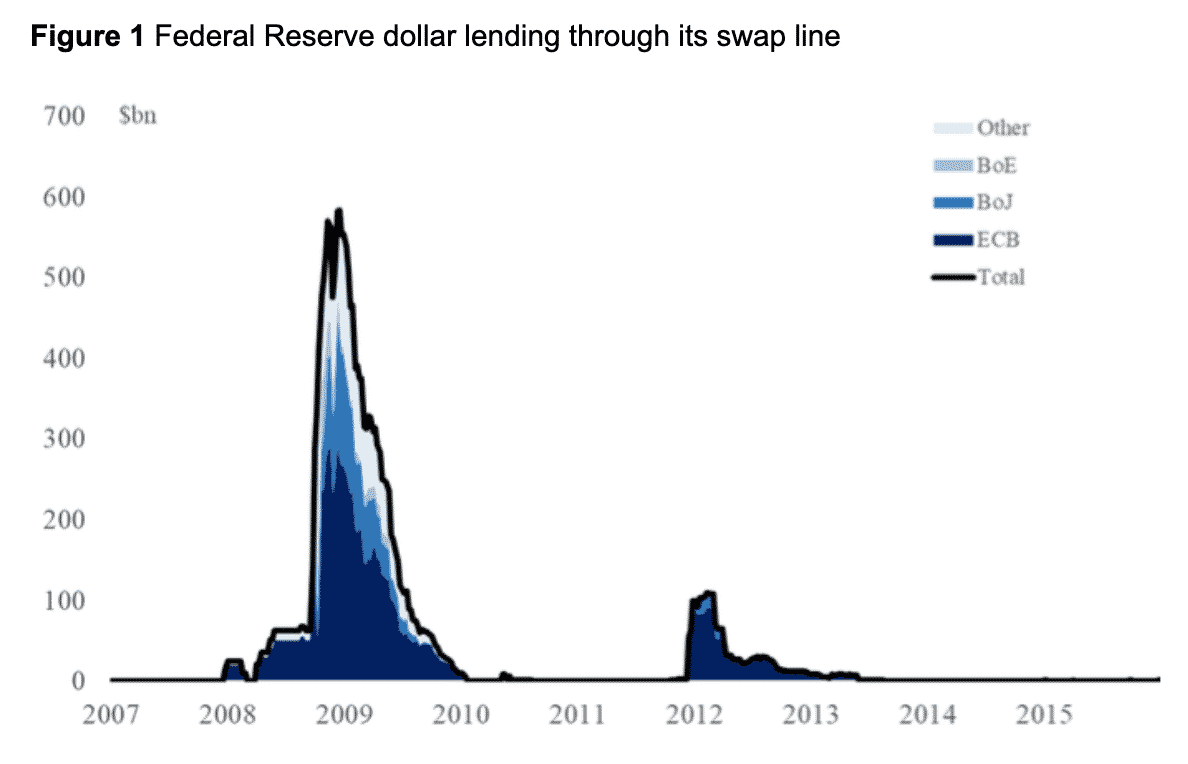

To staunch the panic-stricken demand for dollars, there needs to be a global lender of last resort that can provide dollars on demand. One option is the IMF. The other is the national central bank of the US, the Fed. In the face of the 2008 crisis the IMF was upscaled to meet the demands of a global financial crisis driven by private sector balance sheets rather than developing-country government fiscal problems. At the same time and in direct conjunction with the expansion of the IMF’s lending facilities, the Fed developed a system of liquidity swap lines with its partner central banks.

The swap lines have been the subject of an extensive academic discussion. They were a key theme of Crashed, my history of the crisis.

In the last two weeks the issue exploded back to the forefront of crisis-fighting. On Sunday 15th March – what we will probably come to think of as the second weekend of the financial panic – the Fed and its key partners signaled that the swap facilities institutionalized in 2013 are open for business.

As the news broke, several of us were trying to explain the significance of swaps and calling for more action. Izabella Kaminska at Alphaville took the lead laying out the work of Mathis Richtmann, the managing director of the German macro-finance think tank Dezernat Zukunft

I contributed a couple of short pieces. One in Prospect. One in Foreign Policy.

Thanks to real time analysis of central bank accounts funds by Richtmann and Dan Hinge, we know that funds did begin to be drawn on a substantial scale in the days that followed.

Dan Hinge has an excellent piece at Central Banking which you can download for a limited time only.

To really understand how the ECB was working the swap lines you need to read this twitter thread by the essential Daniella Gabor.

By the middle of the week it was clear that this would not be enough.

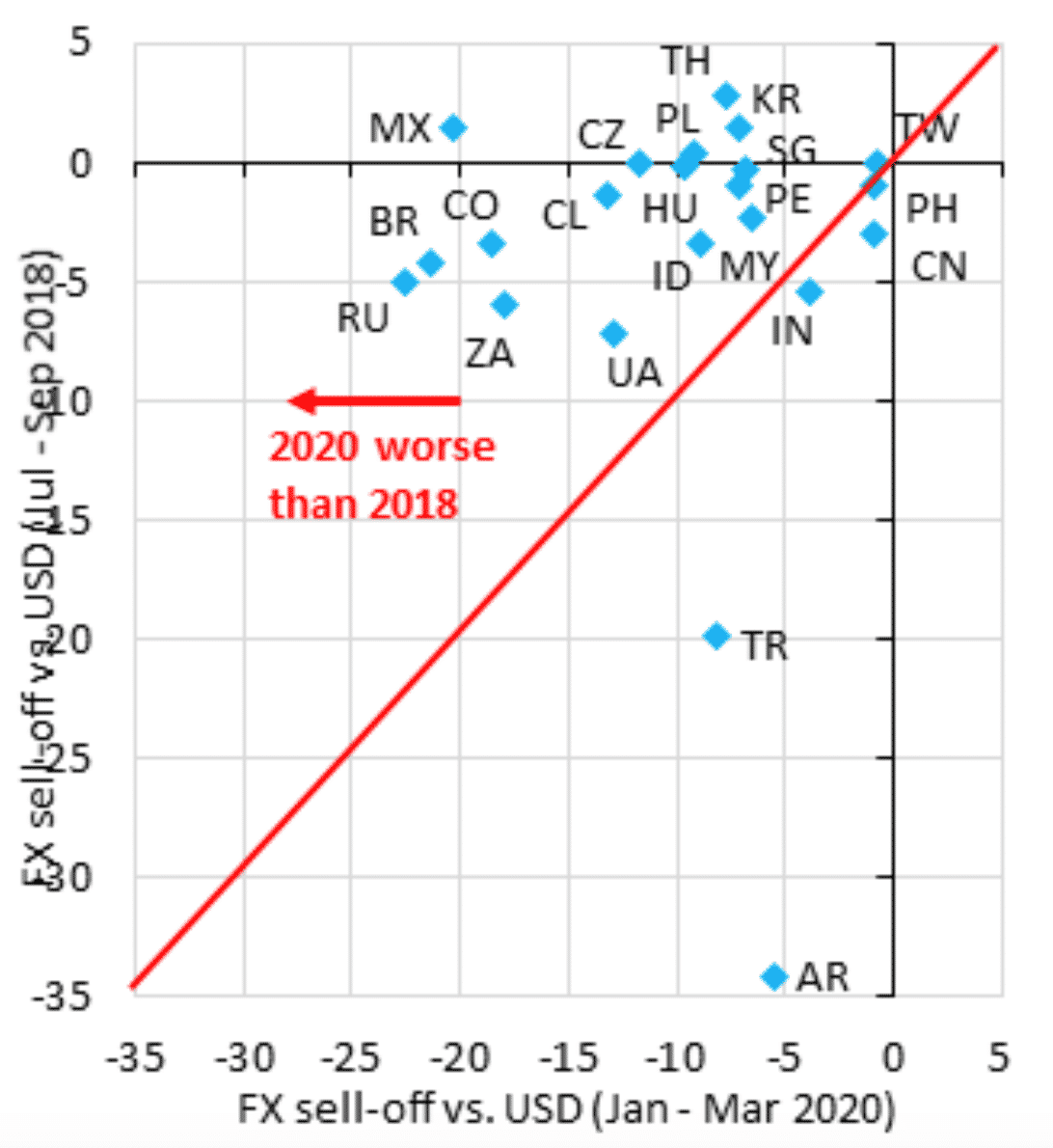

As the IIF economics team led by Robin Brooks has been pointing out insistently, the EM are suffering comprehensive and violent capital flight. This is worse that 2018, 2015-16 and the taper tantrum in 2013.

In response, on Friday the Fed extended the swap lines to a total of 14 countries including Mexico, Brazil and South Korea.

In response, on Friday the Fed extended the swap lines to a total of 14 countries including Mexico, Brazil and South Korea.

In effect, they restored the network of 2008. It was well-suited to that world, the key question I put in a New York Times piece is whether it actually fits the far more multipolar global economy that has emerged in the last 12 years.

Brad Setser is producing a rolling update on the question of global dollar funding. He argues for a repo facility that will enable the PBoC to use its US Treasuries for dollar borrowing without selling them.

Jon Turek’s global mapping is also highly recommended.

Claire Jones at Financial Times seriously canvassed the question of a Fed swap line with the PBoC. She draws on the early note by Pierre Ortlieb of MFIF.

Though it has been drowned out by the panic in the markets and the scale of national central bank action, the IMF has been pushing for concerted global action. This is welcome. But is the IMF in its current dimensions fit for purpose?

In the pages of the FT’s Alphaville Kevin Gallagher, José Antonio Ocampo & Uli Volz address the role of the IMF. As they point out “the harsh truth is that the Fund lacks sufficient resources to deal with a global crisis, and the decision taken last year to postpone the increase in quotas until 2023 came at the worst possible time. its current form, the global financial safety net is patchy: it lacks coverage and resources to deal with a crisis of the magnitude we are currently facing.” The authors call on the IMF to issue SDR’s to the tune of $ 500 bn to provide liquidity to the hardest hit.

As the last weeks have demonstrated, huge shocks are shaking the global financial system. It is a lop-sided construction at the best of times, dominated by its dependence on the US currency. Since 2008 it has not been fundamentally reformed. We were content to rely on the network of relationships put in place during that crisis. They remain dominated by the Fed and what can be broadly described as the “Western alliance”. It remains to be seen whether they are adequate to addressing a truly dramatic shock to a far more multipolar world economy.

Watch this space.