My dear friend Prof Deborah Cohen (Northwestern) invited me to give a short lunchtime talk to the Modern European section of the American Historical Association this year.

This gave me the chance to pull together some of the threads connecting Deluge and Crashed and to organize them around the theme of how to think Europe’s place in the history of our global age.

“Where in the world is America?” That was the question posed, back in 2002, by Charles Bright and Michael Geyer as a prelude to outlining a history of the United States in a global age. Today another question seems even more urgent: “where in the world is Europe?”

Briefly, two years ago there was a delirious moment when the Chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel was nominated as the leader of the free world.

That didn’t last. On the whole the commentary has been decidedly downbeat.

This fall the French economist Jean Pisani-Ferry published a fascinating piece about the mounting global tension unleashed by the Trump administration. At the risk of over-intellectualizing American policy-making he outlined a three-level chess game: 1. a general American pushback against multilateralism, 2. an effort to make China play by the multilateral rules and 3. finally an effort to actually curb and contain China’s rise.

As far as that third game is concerned – the power play that dominates global politics in the moment – Pisani-Ferry’s conclusion was unambiguous and sobering:

As far as that third game is concerned – the power play that dominates global politics in the moment – Pisani-Ferry’s conclusion was unambiguous and sobering:

“Europe, Japan, and Canada are not part of this rivalry – they simply do not matter in the same way that the US and China do.” Europe is inevitably involved. But they did not dictate either the rules of the game, or the moves of the key players.

Pisani-Ferry is a die in the wool pro-European, advisor to Europe’s most pro-European leader, President Macron of France. And his conclusion as far as the most important tension in “global politics” today is concerned is that the Europeans “simply do not matter”.

Meanwhile, the FT’s top economist Martin Wolf, whose words are gospel for much of the commentariat, began the year with a column in which he questioned whether the future really did belong to China. But who else might it “belong” to? Once again Wolf’s judgment is crushing and definitive: “The most interesting other economy is not Europe, which seems destined for a slow relative decline, but India”.

These are just two weighty examples taken from the last few months. The chorus is deafening: Europe does not matter now and will matter even less in future. As someone whose life now involves a daily diet of such material, you can see perhaps why I am drawn back to Dipesh Chakrabarty’s fascinating classic of 2000: Provincializing Europe. Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference.

These are just two weighty examples taken from the last few months. The chorus is deafening: Europe does not matter now and will matter even less in future. As someone whose life now involves a daily diet of such material, you can see perhaps why I am drawn back to Dipesh Chakrabarty’s fascinating classic of 2000: Provincializing Europe. Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference.

Chakrabarty’s title is taken from a gloomy meditation by the Heidelberg philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer. Chakrabarty’s work itself is a brilliant exercise at the intersection of intellectual and political history and the philosophy of history. But to frame his argument this is how he starts:

Chakrabarty’s title is taken from a gloomy meditation by the Heidelberg philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer. Chakrabarty’s work itself is a brilliant exercise at the intersection of intellectual and political history and the philosophy of history. But to frame his argument this is how he starts:

“This is not a book about the region of the world we call “Europe”.

Why not? Because, Chakrabarty continues: ”That Europe, a region of the world, one could say, has already been provincialized by history itself. Historians have long acknowledged that the so-called “European age” in modern history began to yield place to other regional and global configurations toward the middle of the twentieth century. European history is no longer seen as embodying anything like a “universal human history.” No major Western thinker, for instance, has publicly shared Francis Fukuyama’s “vulgarized Hegelian historicism” that saw in the fall of the Berlin wall a common end for the history of all human beings. The contrast with the past seems sharp when one remembers the cautious but warm note of approval with which Kant once detected in the French Revolution a “moral disposition in the human race” or Hegel saw the imprimatur of the “world spirit” in the momentousness of that event.”

What for Chakrabarty still demands intellectual work is not the provincialization of the “region of the world we call Europe”. That is an accomplished fact. The ghosts that needs to be laid to rest are Europe’s ideas. And it those ghosts that he pursues into the intellectual history of colonial India.

But it is Chakrabarty’s very first sentences that preoccupy me. There we find him in resounding agreement with commentators like Pisani-Ferry and Martin Wolf. “Europe, one could say, has already been pronvicialized by history”.

That throwaway line gives me pause for thought.

(1) As a European it poses a no doubt healthy challenge to one’s self-esteem.

(2) It gives pause politically. Does Europe really have to be as irrelevant as it is? Is its provincialization necessary or to a large degree self-inflicted?

(3) It gives me pause also professionally. What does it mean for the future of European history and other cognate fields such as European Studies, that Europe is widely seen, no longer to matter?

(4) But it also gives me pause for thought intellectually. Of course I get it. I fully understand the attractions of the global and have myself made no attempt to resist them. But what about this historical dismissal of Europe that Chakrabarty performs no less off-handedly than Wolf and Pissani-Ferry?

What is this force that Chakrabarty invokes, “this history” that has ALREADY by ITSELF done the work of provincializing Europe?

You can see the point that I am driving at.

Is it not somewhat perplexing that the dethroning of Europe and its philosophies of history should be declared in such triumphantly Hegelo-European tones? History rises from the dead, as in a second coming, to announce the end of the end of history.

This kind of twisting effect is not, of course, lost on Chakrabarty. It is the stuff of his book. But to find it at work in the very opening sentences, quite unconsciously it seems to me, to find it so operative in the most common-place assumptions that frame our sense of where we stand today, is nevertheless thought-provoking.

In this short piece, at the risk of disjointedness, I want to make two distinct points each of which aims to destabilize this monolithic sense of Europe’s provincialization and to offer a suggestion, also drawn from Chakrabarty’s opening lines, about how we might think more productively about the flux of our present moment.

Let us start with the familiar ambiguity in the word history. Does history, in the sense that Charkrabarty is using it, refer to actual events, processes, structures, or to retrospective discourse about them? When Chakrabarty says, “Europe has already been provincialized by history itself”, does he mean that Europe was provincialized by the Marshall Plan and decolonization, or does he mean that from the mid twentieth century Europe has been repositioned in the narratives of historians? My guess is that he means both and that he views them as enmeshed with each other.

I

Let us take the historiographical side first. It is surely right to say that around the mid 20th century something began to change in the way in which modern history was narrated, which tended to decenter or provincialize Europe. It is a phenomenon that first struck me when I was struggling to finish Deluge my book from a few years back about WWI and its aftermath. What struck me was an inward turn in several of the most influential works of European history composed in the 1960s and 1970s. That is not surprising. The times they were a changing. Decolonization under the sign of an American led Cold War produced a narrowing of horizons. The Suez debacle in 1956 was humiliating. But rather than bringing about a new synchronization, a new fit between narrative and reality – history in and history for itself converging in Hegelian panorama of the setting European sun – what we run up against when we return to those classic texts and debates of the 1960s is a new torsion, a weird, warping, anachronistic effect.

What do I mean?

Well to start with historical discourse unlike philosophy or politics stands constitutively in an ambiguous relationship with its own time. The historians of 1960s and 1970s were not writing about 1960s and 1970s they were writing about the past. The ones I was interested in were writing about early 20th century when, in fact, world power in fact still did revolve around Europe. The effect of Europe’s new mid-century humility, perversely was to render the early twentieth century, the first age of globalization, globalization under the sign of empire, in terms that are more reminiscent of the post-colonial, provincialized, nationalized Europe of the 1960s and 1970s. The result was certainly provincializing but also distorting. A particularly important liminal case, certainly for a German historian, is Fritz Fischer and the debate he triggered in 1961 about the outbreak of World War I.

Fischer’s Griff nach der Weltmacht was anything but a parochial book. But that is what the debate he unleashed made of it.

Think about the title. How was Griff nach der Weltmacht (Bid for World Power) translated into English? Germany’s Aims in the First World War.

The reference to the world dropped out. The first couple of chapters of an enormous book that if not a global history could at least be described as a history of “Germany and the world” launched an infuriatingly narrow debate about German strategy. In the subsequent years of argument this became ever more focused on Berlin’s blank cheque guarantee to Vienna in the July crisis of 1914. As Jennifer Jenkins has commented perspicaciously in her Journal of Contemporary History article of 2013 this meant ignoring what most of Fischer’s book was actually about.

The question of the outbreak of the Great War, which was widely seen at the time as emerging out of global imperialist competition, was recast from the mid century in more local terms. What was lost from view was the dynamic competition of global expansion. Explanations of 1914 now start earlier, in 1900 or 1905 or 1911. But they still terminate in August 1914. They do not generally take in the expansive dynamic that brought in Italy, Bulgaria, Romania, the United States and Greece. And yet it was this escalatory dynamic that was crucial for Fischer. It motivated his treatment of Imperial Germany’s strategy of revolutionary warfare and his focus on the escalation of the later war years at Brest Litovsk and in Erich Ludendorff’s increasingly excessive vision of total war etc etc.

Much of the work we have been doing in recent decades to reglobalize WWI, I would argue, is necessitated by the provincialization that was imposed on our narrative in the inward turn of fifty years ago. This is not to suggest that the first wave of commemoration and history writing in the 1920s and 1930s did justice to colonial soldiers in the way that we would demand today. But likewise no one was in any doubt about the imperial contribution. In the wake of 1914-1918, it was essential to the politics of empire and the legitimation of claims within an imperial framework. My hypothesis is that as that imperial political imperative became largely irrelevant from the 1960s onwards, historiographical horizons fragmented and shrank.

The provincialization of Fritz Fischer is a particularly striking example, but to put more flesh on this thesis consider two further examples.

Recall how Arno Mayer narrated the history of the war’s aftermath in Political Origins of the New Diplomacy, 1917–1918 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1959) and then in Politics and Diplomacy of Peacemaking: Containment and Counterrevolution at Versailles, 1918–1919 (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1967). The subtitle says it all. The central contest is between Wilson and Lenin. The issue at stake is containment. Mayer back-projected the politics of the high cold war of the early 1960s into the global politics of 1918-1919. What is the effect? To decenter Europe. Europe is the battlefield of course but as in the Cold War the key actors are the United States and the Russian revolutionaries. A figure like Clemenceau shrinks to a wizened French nationalist. Lloyd George reduces to a quicksilver welsh cynic. Both are seen as betraying progressive liberalism’s promise in favor of a narrow reactionary counterrevolutionary politics. The best hope of the world is the vacillating Wilson administration, a disastrous disappointment not made good until America’s decisive modernizing intervention after 1945.

The result is a flattening of European politics in the early 20th century, which Mayer would later radicalize with his astonishingly reductive thesis about the persistence of the ancien regime.

If you, in fact, examine Clemenceau’s biography you find a globe trotting cosmopolitan trans-Atlantic radical effectively bilingual in English. Likewise if you want to understand the spread of the language of “self-determination” across the globe, as far as the British empire was concerned what matters are not Wilson’s vague promises, but the home rule politics and the bloody example of Ireland. For the European left, the French socialist and the British Labour party, Wilson might serve as a cudgel with which to belabor Clemenceau and Lloyd George. But ironically Wilson was himself an aficionado of Gladstone and Mazzini. And if the Soviet regime actually envisioned a global antagonist in the early 1920s, if there was a first Cold War in the interwar period, its antagonist was not the US but the British empire.

So the Fischer debate turned a global history book into a debate about Germany and the blank check for Vienna. Mayer redescribed Versailles as an arena for a first iteration of the cold war.

My third example comes from a decade later, Charles Maier’s astonishing 1975 PhD book, the Recasting Bourgeois Europe.

As every grad student of 20th c European history will know, this is a dauntingly complex analysis of corporatist politics in the aftermath of World War I. But what is also striking is what for Maier, bourgeois Europe consisted of – Germany, France and Italy.

Those are, of course, the three largest continental European countries and those most intensively studied. But if the question to be examined is the financial and industrial politics of bourgeois reconstruction, then the selection is not innocent. Not only are the colonial empires of France and Italy entirely missing. But in the politics of postwar financial stabilization, none of Maier’s case study countries was really a sovereign actor. The terms of stabilization were set by the United States and Great Britain, with regard to war debts, reparations and monetary policy. They set the pace with their deflationary push in 1920. And it was those two powers also that brokered the naval arms deal at Washington in the fall of 1921 that went a long way to dampening military spending and imperial rivalry. Those were the powers that set the parameters for bourgeois stabilization within which Maier’s continental European drama then unfolded.

Of course, to have included the British Empire would have been a huge challenge. Monumental as it is, Recasting is a PhD. But there was also, I suspect a broader provincializing historical vision in effect, if not in Maier’s own conception then in the reception of his work. Maier’s bourgeois Europe is the Europe of the postwar, the Europe of the 1950s, the Europe of the Coal and Steel Community and the Treaty of Rome. That is also the world of the classic era of comparative European history from the 1960s forward.

In economic history we know this as the era of the “Keynesian welfare state”, the era between the great ages of globalization, the era of the “great compression”. It was the period which witnessed the formation of compact national economic, social and political systems. And as David Edgerton has recently argued in his brilliantly iconoclastic history of modern Britain, that had a historiographical counterpart. After World War II Europeans rewrote their histories in national welfarist terms

The bracketing of Britain and its empire from Europe’s 20th century history has a spectacularly provincializing effect. Not only did it sanction the elimination of everyone else’s imperial history. But it impacts our understanding of Europe’s broader relation to the world more generally, since especially for the lesser European colonialists, those connections so often ran through networks and frameworks shaped by the British.

All in all, Chakrabarty is right. Historical writing really did provincialize Europe from the mid-century. But the effects of that sudden and traumatic process were weird. They involved the production of a history of Europe’s 20th century that was not just short, in Eric Hobsbawm’s terms, but narrow: several sizes too small to fit the realities of the early 20th century.

II

One could multiply examples. But, instead, let me turn to the other dimension of what history’s provincialization of Europe might mean. And let me focus on Chakrabarty’s invocation of the great event that marks the end of the Cold War in Europe, 1989. “No major Western thinker”, he tells us, “has publicly shared Francis Fukuyama’s “vulgarized Hegelian historicism” that saw in the fall of the Berlin wall a common end for the history of all human beings.”

Really? Well first of all you would need to bracket Jürgen Habermas who from the 1990s did see the widening and deepening of European integration after 1989 as the forerunner of a more universal cosmopolitanism.

But, more importantly, you would need to exclude from the class of “major Western thinker” pretty much the entire profession of economics. Economists did indeed see in 1989 the ultimate and conclusive proof of the non-viability of communism and the universality of the market model.

The grand narrative of the market revolution has at least two distinct subplots: globalization and neoliberalism. I don’t want to get into hair splitting about definitions of either of those here. What I want to highlight is a rather striking tension between these two master narratives of the history of the present: a tension that might best be characterized as geo-intellectual.

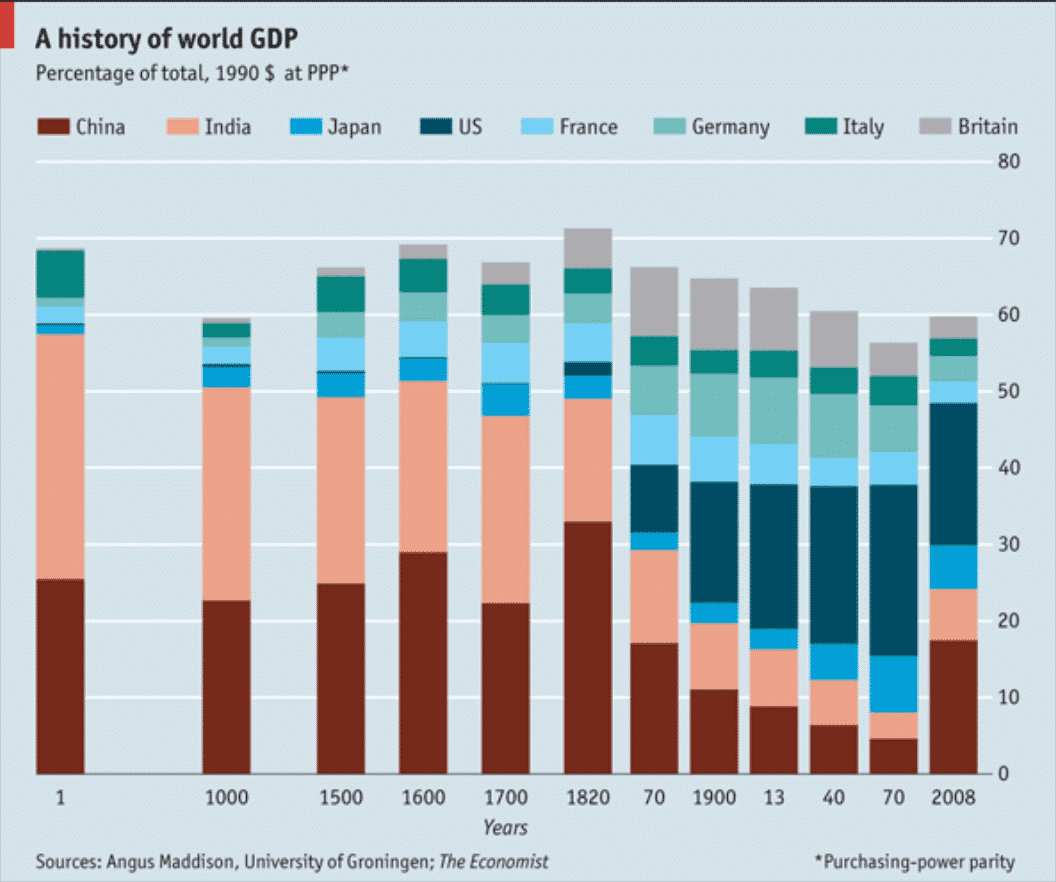

On the one hand we have the narrative of globalization that Chakrabarty, Pisani-ferry, Wolf are all invoking. This is defined precisely as the waning dominance of the West in the global economy. Seen in the rearview mirror this can indeed make 1989 appear like no more than a local European event. With hindsight the Tiananmen square massacre and the survival of the Communist regime in China may matter more than the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of Soviet power in Europe.

Contrast this with the narrative of neoliberalism, which, when investigated closely, has a surprisingly old world genealogy. Quinn Slobodian has recently reemphasized this with his brilliant and aptly titled book Globalists.

As he shows, the preoccupation neoliberals with the construction of a supranational framework of economic order capable of containing the explosive force of economic nationalism emerged in the context of Europe’s first post-imperial moment, not after 1945, but in Vienna after 1918.

As he shows, the preoccupation neoliberals with the construction of a supranational framework of economic order capable of containing the explosive force of economic nationalism emerged in the context of Europe’s first post-imperial moment, not after 1945, but in Vienna after 1918.

Stubenring 5-12 Vienna where von Mises had his offices in the Chamber of Commerce.

It is not by accident that Austrian economists are key to the early history of neoliberalism. It was the collapse of the Habsburg Empire that prompted them to find a new depoliticized framework for liberal economics.

Thus Europe spawned not only the EU as a supranational body, which Habermas et al see as the harbinger of a better model of transnational politics. It also was the incubator, by way of neoliberalism, for the global architecture that would replace empire and secure global capitalism in an age of postcolonial nationalism. As Slobodian shows, the key architects of the WTO’s global trading order are not MIT-trained star economists, but obscure German lawyers. If you want a European history that avoids precisely the problem of premature provincialization that was characteristic of writing from the 1960s, Slobodian would be a perfect reply. He gets the complex trajectory of the downsizing of Europe right with the surprising result of recentering Europe at the heart of global political economy.

Nor is this merely a matter of the history of ideas and their politics. As Rawi Abdelal showed in his 2007 book Capital Rules: the construction of global finance, the European influence extended to the engine room of global political economy.

The most essential element of what became known from early 1990s as the Washington consensus – the absolute liberalization of capital movement – was formulated and promoted as a general system not from Washington but from Paris, not by British or American financial economists but by disillusioned French socialists, the likes of Jacques Delors, Michel Camdessus and DSK. Why? Because what they realized in the wake of the failure of the Mitterrand experiment in 1983 was the impossibility of making social democracy work in a medium sized European economy. What they wanted instead was a global system of rules in which a unified European currency would stand alongside the dollar.

And this had practical consequences. As globalization transformed circuits of trade and supply chain integration and brought hundreds of millions of people in Asia into the factory workforce, the neoliberal vision of radical market liberalization was most fully realized not in economic relations with China, but in the financial markets of the North Atlantic, the old cradle of the modern world economy. One of the great surprise for those of us interested in unearthing the history of the financial crisis of 2008 was precisely this North Atlantic geography. We refer to 2008 as the GFC, the global financial crisis and the crisis did have ramifications around the world, but its hub was in the North Atlantic.

And, tellingly, this was a historic surprise. Right up to the spring of 2008 it is striking how far Asian-centered globalization dominated the discussion of economic policy on both sides of the Atlantic. For good reason. The rise of China is quite simply the greatest story in economic history. Ever. Bar none. Including Europe’s industrial revolution. And this was shaped in a special relationship with the United States, which Niall Ferguson and Moritz Schularick dubbed Chimerica.

But the Sino-American story has a peculiar and in some ways quite old fashioned logic. It is a story of industrialization and trade. It is a story of lending by Chinese sovereign wealth managers to the US government, across exchanges controlled on the Chinese side in ways that are reminiscent of the Marshall Plan era. This is a story of national economy-on-national economy relations. One could imagine a Sino-American crisis and before 2008 many people did. But that is not the crisis that actually transpired. The crisis that almost destroyed the world economy ten years ago was not between China and the US but between the US and Europe in the private market-based banking system enabled by the great trans-Atlantic liberalizing partnership since the 1960s.

Here is a map of the global financial system before 2008.

You can see how it pivots not on the Sino-American but on the European hub. As a result the buried story of crisis management is a transnational story, the latest installment in trans-Atlantic financial diplomacy that goes back to World War I. What was reawakened in a shadowy way which no longer bears much public exposure and celebration, were connections that go back to gilded age. Of course, when we say that “European” banks were at heart of crisis, we are talking about Americanized, dollarized transnational financial entities. That is the dark European secret of 2008. None of Europe’s banks would have survived without dollar liquidity pumped in by the Fed. But the trans-Atlantic relationship is one of deep symbiotic interdependence. The city of London, Frankfurt and Paris were all too big for the Fed to allow them to fail, second only to wall street. The dollar system that superseded the sterling system after 1945 is a distributed trans-Atlantic network with minor hubs in Tokyo, Singapore and now in Hong Kong and its center in the Wall Street-City of London-Paris-Frankfurt network. It was built around the Eurodollar market. It still is. Ten years later this is how the interlocking balance sheets of the global banking system looks, as mapped by the Bank of England.

In light of this, how do we make sense of those loudly proclaimed statements of Europe’s irrelevance with which I began and which unified Pisani-Ferry, Wolf and Chakrabarty?

Well perhaps you might say they are predictive as well as descriptive. Europe’s provincialization is only now really beginning. We may have reached a tipping point, a moment of inflection, a point of no return in Europe’s long decline into provinciality. The financial crisis of 2008 did irreparable damage. What Pisani-Ferry and Wolf are reacting too is the dismal record of the Eurozone since 2008.

But we should be alert to two other possibilities. First there are strategic reasons for Europe to provincialize itself. The Commission right down to the present day is in business of minimizing involvement of the Europeans in US subprime disaster. At the same time they stylize the Eurozone crisis as a peculiarly European affair involving constitutional politics and the issue of Greece. The Europeans continuously and actively produce their own discursive provincialization. Globalization is presented as something that “happens” to Europe from the outside rather than being something that the EU and European corporations contribute to as important hubs of world trade and finance not to mention through their toleration and active encouragement of outrageous tax evasion by global corporations. Why adopt such a position of deliberate obscurity and marginality? Well, think Switzerland. What could be more provincial? What could be more profitable? It is a mode of free riding at the expense of history and political agency.

But more fundamentally, what the map of global financial interconnection highlights is the inadequacy at a conceptual level of any history that is overly unitary, that sees a single progressing front which sweeps forward and divides the world between the leading and backward edge. There are multiple networks each with its own peculiar geography of combined and uneven development. To grasp this reality, the very idea of provinciality is unhelpful, suggesting as it does a clear center and a clear periphery. Such hierarchies do exist but they need to be understood as just one amidst a field of options for complex totalities structured in dominance.

So how might we better envision this? Right there in Chakrabarty’s opening paragraph, for which I am so grateful, in the third sentence is a better version. This one: “Historians have long acknowledged that the so-called “European age” in modern history began to yield place to other regional and global configurations …”. “Configurations” seems precisely the right term to grasp the kind of complicated geometry you see in pictures like this. And these are of course in one dimension only, money denominated in dollars. Draw something similar for multiple dimensions, overlay and interrelate them and you begin to have something more adequate to capturing the flux of our moment. Let us talk of Europe’s shifting place amidst reconfigured global networks, not its provincialization.

For me this train of thought called to mind a wire sculpture by the émigré Venezuelan-German artist Gego, whose work I saw in Paris last year.

And then I realized that precisely that imagery is in fact the boilerplate of corporate and business school iconography.

Something to ponder. What would a critical network analysis look like? I am sure there must be such a discipline. How do we put the dominance back into the notion of complex totalities (structured in dominance)?

Something to ponder. What would a critical network analysis look like? I am sure there must be such a discipline. How do we put the dominance back into the notion of complex totalities (structured in dominance)?