In picking Kristalina Georgieva, the Bulgarian chief executive of the World Bank, as their candidate to succeed Lagarde at the IMF, the EU made the best of a bad choice. To have picked Dijsselbloem would have been a disaster.

But the manner in which Georgieva was picked not only leaves the EU divided – she gained only 56 percent of the vote – but also confirms the illegitimacy of the entire process.

It is by historical convention that it is the Europeans who pick the Managing Director of the IMF. It is part of the Bretton Woods carve up that handed the World Bank job to the Americans.

Why should the rest of the world accept a new head for the IMF decided by politicking by a group of small to medium-sized European countries which no longer play the role in the global economy that they once did, whose recent track record of economic policy is miserable, who have entangled the IMF in the shambles of the Eurozone and whose weight is set to dwindle in future?

In this piece for Social Europe I made the case for the competition to be opened to suitably qualified candidates from around the world. Several other folks have made similar arguments.

The balance of opinion is hardly surprising. How, after all, could anyone mount a cogent defense of the existing arrangement?

But agreeing that we must go beyond the Bretton Woods deal of 1944 is just the beginning of the discussion. The question then becomes what criteria should be used to decide a new balance of quotas and voting rights on the IMF board.

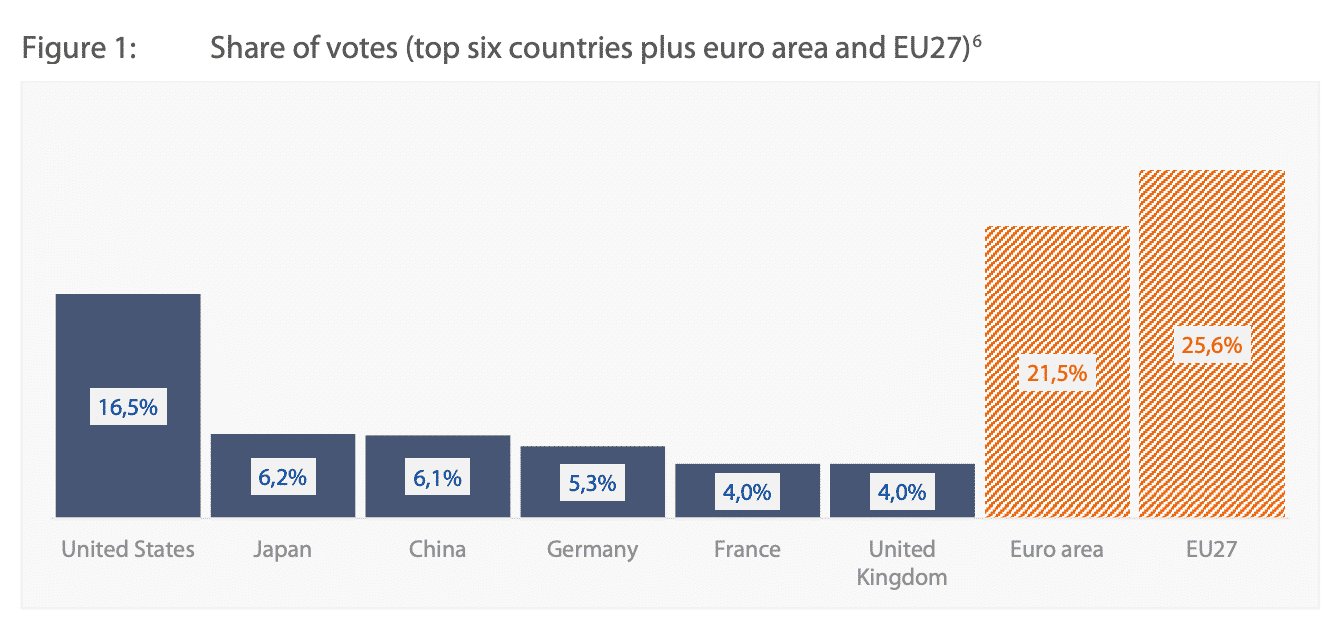

Currently voting rights at the IMF are distributed as follows.

source: European Parliament Brief

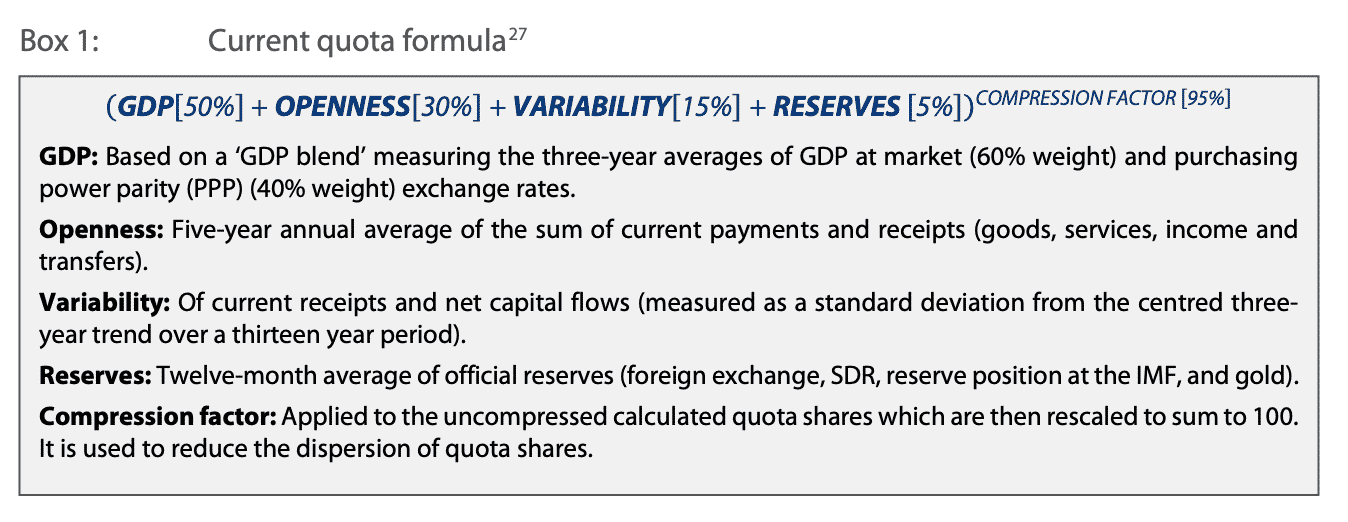

Voting rights are decided by a somewhat more rational mechanism than the convention that gives the Europeans the right to pick the person for the top job. The formula that is notionally used to decide the composition of the IMF Board is a weighted average of four factors.

source: European Parliament Brief

The formula makes clear why the balance is as skewed as it is. The Europeans score highly in terms of GDP measured in market exchange rates and openness.

Another way of thinking about it would be to say that the IMF Board reflects the distribution of international banking in the early 2000s before the crisis. On that basis you can see why the Europeans would have the votes that they do.

Setting aside the question of whether this is an appropriate base on which to decide the power balance at the IMF, if one were to apply this formula strictly it would involve a major shift in favor of China.

source: European Parliament Brief

By reducing the US below the critical 15 percent threshold, this would deprive Washington of its veto over Board decisions (which require a 85 percent majority) and would fundamentally upset the politics of the IMF.

Setting aside the question of whether the American Congress can actually be persuaded to vote constructively on the issue, if we imagine a reasonable discussion about the most minimal reform, would the solution lie in a combination of two changes:

(1) a reallocation of shares in favor of the EM

(2) combined with an increase in the majority required for decision-making, say from 85 to 90 %.

This would make the board more “representative” of the world economy today whilst giving a veto to the US, China and any substantial coalition of Europeans plus Japan. Or would that render the body dangerously incapable of making decisions?

Deadlock would be bad. The IMF matters, especially in a crisis.

In a piece I did for the Fund’s anniversary earlier this year, which I wrote before the current round of musical chairs began, I outlined some of the more fundamental issues of policy that need to be on the Fund’s agenda.

It remains as urgent as ever.