Amidst all of the debate around Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, I was shaken this week by a typically salutary thread by Alan Allport on the anniversary of another bombing. Eighty years ago, in a ten-day joint operation, American bombers by day and British bombers by night destroyed a large part of the German industrial and port city of Hamburg.

On the ascending curve of aerial attacks on cities – a terrifying vision that haunted the 20th century – a crescendo that started in earnest in Guernica in 1937 and continued with the attacks on Warsaw, Rotterdam, the London Blitz and Coventry, after the RAF’s 1000-bomber raid on Cologne in 1942 and the sustained campaign against the German industrial centers of the Ruhr in the spring of 1943, Hamburg marked a point of culmination. It was the first aerial attack that came close to fully destroying a big city and rendering it at least temporarily uninhabitable. It was an important way-station en route to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

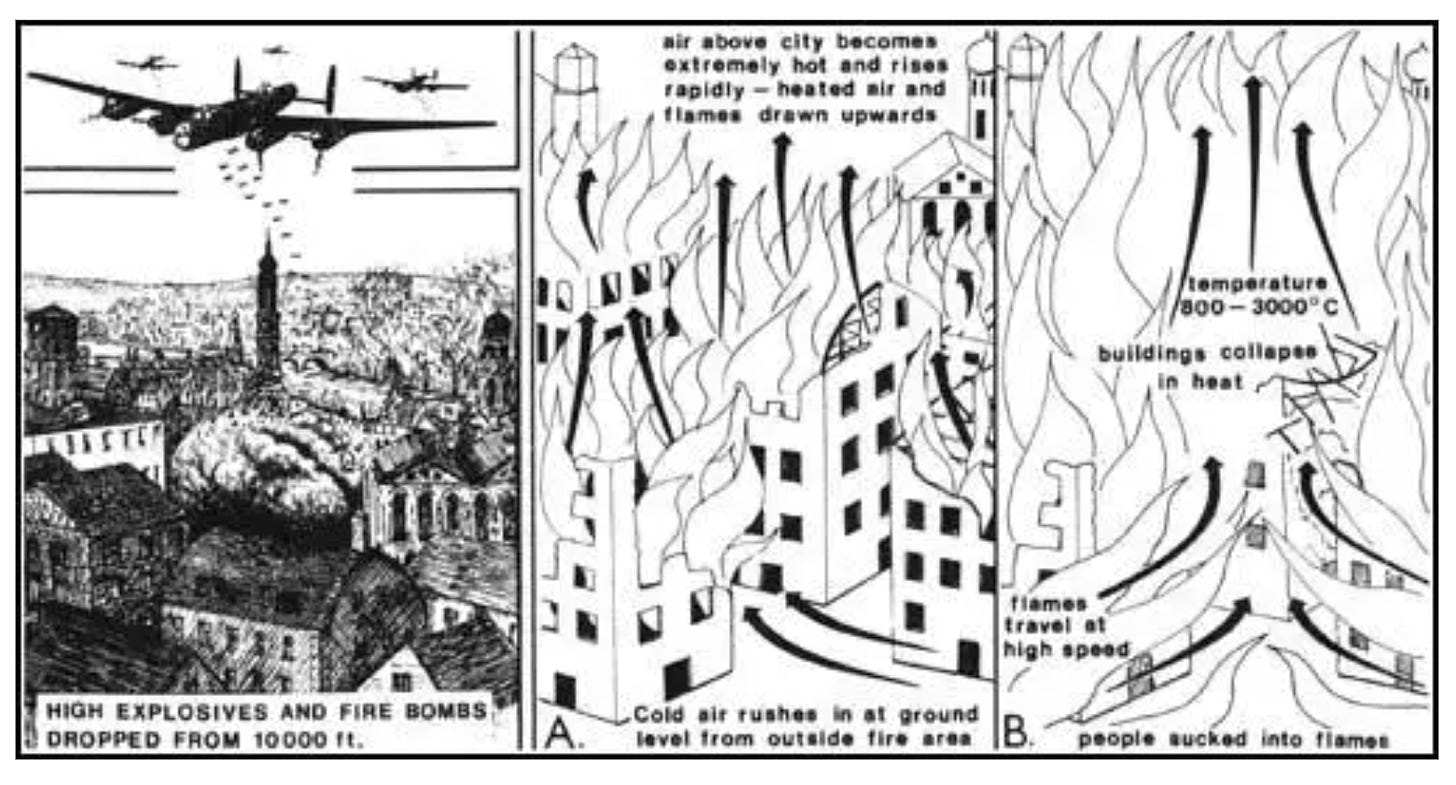

In Hamburg two-thirds of the city’s housing stock was damaged or destroyed. The death toll is imprecise, but something like 40,000 people were killed by the bombs and the firestorm they unleashed. A cocktail of high explosive and incendiary bombs were used to turn Hamburg’s tall tenement buildings into furnace chimneys. Giant block buster bombs destroyed underground water pipes to stop the fires being put out. Bombs with timed fuses spread fear amongst the fire crews many of which included camp inmates.

The temperatures generated by the fire storm were unprecedented and anticipated those of the atomic explosions to come. Glass and metal melted. Bodies were mummified en masse.

In the aftermath, one million people were forced to flee the city in panic. In Berlin, in Albert Speer’s Armaments Ministry the mood was apocalyptic. If the British and American bombers could do this to any German city at will, Speer remarked that the German economic planners might as well put a bullet in their brains.

As it turned out, Hamburg was hard to replicate, though the bombers tried. In October 1943 they managed to unleash a fire storm in Kassel. From 1943 onwards, Berlin was repeatedly attacked, but never with the same results. In 1944 as Allied aerial superiority became ever more overwhelming, the list of cities suffering serious attack grew longer and longer. But in Europe only the attack on Dresden on 13-14 February 1945 measured up to the intensity of Hamburg.

The most devastating single aerial attack of the war came not in Europe but in Japan, with the firebombing of Tokyo on March 9-10 1945, which likely killed over 100,000 people. The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 was not an isolated or unprecedented act of urbicide. It was the deliberate and long-planned extension of a campaign that first showed its terrifying potential in Hamburg 80 years ago.

If aerial bombing was the most concentrated expression of modern industrialism and the unleashing of the atomic fission is one possible marker for the dawn of the anthropocene, then the ascending curve of the British and American bombing effort that began in earnest in 1943 might well be taken as the origin point of what environmental historians call the “great acceleration”.

This was, as many historians have argued, the quintessential expression of particular type of high-tech warfare, of which not Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union (preeminent in land warfare) but Britain and the United States were the leading exponents. It is not for nothing that some have suggested that we speak not of the Anthropocene but the Anglocene (Bonneuil and Fressoz).

Allport puts it very well.

I would not necessarily associate Allport with this line, I want to excuse him if he does not share this view, but both David Edgerton and I regard strategic bombing as a weapon that was chosen not merely accidentally by Britain. It was not just a matter of industrial capacity and the lack of alternative means to strike at Germany after 1940. Maximum effort strategic bombing was a distinctly liberal mode of war-fighting. For me the key reference point remains David Edgerton essay on “liberal militarism”, which somehow slipped past the editors at New Left Review in 1991.

As Edgerton argues, conventional narratives of British power have a hard time acknowledging where power and resources have historically been concentrated within the British state. And this goes for many critical takes on British imperial power as well. As I put it in reply to Enzo Taverso some time ago, strategic air war was a

distinctively liberal mode of total war – deploying a comparative advantage in high-tech weaponry to disrupt the enemy home front, while satisfying the desire for punishment and putting only a relatively small number of personnel in harm’s way. Antony Beevor recently remarked that the mediocre fighting performance of the British army on D-day and its tendency to rely on bludgeoning firepower reflected a“trade union consciousness”. Though dripping with contempt, it is a phrase that points to precisely what is missing from Traverso’s study of the politics of the age of extremes. Traverso prefers the martyrs of the communist resistance to the tea-drinking Tommies who crushed nazism with weapons of mass destruction. He insists that we learn more from the vantage point of the vanquished than from that of the victors. But the result is a caricature, which falls short of its own commendable ambition. If the aim is to destabilise liberal complacency by showing how civil conflict was sublimated into the great wars that shaped contemporary Europe, we need a more capacious and less literal-minded account than this.

Right the way back to “light-touch” aerial policing of the Middle East after World War I – Empire on the cheap that avoided putting “boots on the ground”, as Churchill argued – airpower has been an essential element in the arsenal of liberal (imperial) power. Another way of thinking the connection to liberalism – more Schmittian in its inspiration – has been more recently provided by Nick Mulder and his brilliant study of World War I, the Allied blockade and the economic weapon.

If as Geoff Mann argues, the essence of Keynesian liberalism is the way that it operates on the boundary between the economic and the political, then strategic air war is the militarized version of that. Not for nothing the analysis first of the blockade and then of the air war, was a high-road through which economic expertise entered modern government. The list of luminaries involved in the 1940s in the analysis of strategic air war is extraordinary. That the economists were often critics of the bombing campaign highlights the double-edged quality of expertise and its engagement in politics. Modern government engages in perpetual self-problematization. It is a place where, in Natasha Lennard’s terms, certainty and uncertainty mingle.

Alan Allport’s thread offers an excellent list of suggested reading on Hamburg and the history of bombing. From the German side I would add Alexander Kluge’s Air Raidwhich like Middlebrook, Deighton and others explores the radical modernist, multi-perspectival nature of the bombing war.

Kluge who went on to be one of West Germany’s leading cultural and critical theorists survived the war in Halberstadt which on 8 April 1945 was subjected to a devastating and yet largely accidental attack. This from the Suhrkamp webpage.

1.5 million cubic metres of debris and rubble: On April 8, 1945, the German city of Halberstadt was heavily bombed by US-forces. The American bomber squadrons had been redirected to Halberstadt as their originally intended targets were hidden under cloud cover and it was too late for them to turn back to their base. And Halberstadt, which, as a mid-sized city without any special industry or any strategic importance, wouldn’t have been on the radar of the Allied Forces, had to bear the brunt of the final days of World War II.

Thus Halberstadt entered the list of destruction that ends with Nagasaki five months later.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.