The Adani conglomerate, the business group most closely associated with Modi’s India, is under serious attack in the stock market, following a damning report by researchers at Hindenburg the outfit that specializes in short-selling overhyped tech stocks.

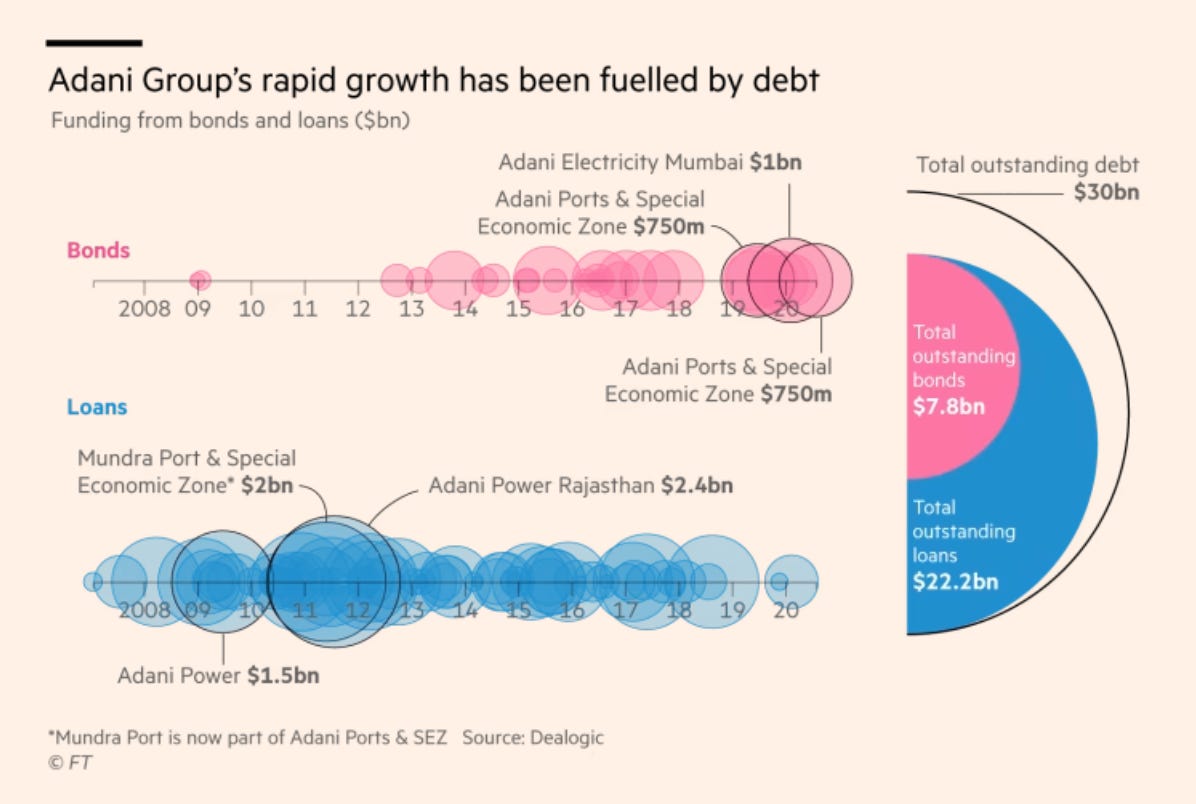

Source: FT

By early Friday morning New York time, Adani’s group had lost $51bn in value. This is a shocking blow to a business that is synonymous with the success story trumpeted by Delhi and the BJP leadership.

The slump in Adani shares follows breathtaking gains in recent years, including some of Asia’s biggest returns in 2022. The five-year advance in Adani Enterprises trumped even the likes of Elon Musk’s Tesla Inc., vaulting Adani from relative obscurity into the ranks of the world’s richest people.

It is hard to exaggerate Adani’s pivotal significance to the story of India’s rise. Founded in the 1980s as a commodity trading group, Adani has become a conglomerate of both national and global significance. In 2022 he crowned his rise to national prominence as “India’s businessman” by acquiring the three national channels of the NDTV television network.

As Bloomberg reported in September Adani’s rise has literally driven the indices.

Indian billionaire Gautam Adani’s ascent to rank as the world’s second-richest person has helped fuel a world-beating jump in the nation’s stocks and bolstered their clout among emerging-market equities. Eight firms controlled by Adani’s ports-to-power conglomerate, including recent cement acquisitions, have contributed more than a fifth of the 109-member MSCI India Index’s surge since end-June, data compiled by Bloomberg show. The index has outpaced Asian and emerging market peers during the period with a 12% jump.

Since 2020, the surge in Adani’s stock price has easily topped all of the madness in America’s equity markets.

Source: Ashok Mody, India is Broken, forthcoming Feb 2023

As Mody makes clear in his forthcoming book, India is Broken, the rise of Gautam Adani is deeply connected not just with rise of Indian equity market but more specifically with Modi’s vision & the Gujarat connection. As the FT reported back in 2020. Adani’s firms own everything from ports to coal mines.

“Nation building” is Mr Adani’s motto and he likes to talk about helping India achieve energy security.

Adani’s reach extends beyond India to highly controversial mega coal projects in Australia. More recently, the Adani group has positioned itself at the forefront of India’s dramatic Green energy projects. As the Economist reports:

Gautam Adani, the group’s founder and chairman (whose personal fortune of well over $100bn makes him one of the world’s richest people), claims his companies will spend $70bn on greenery in India by 2030. With nearly 5gw of solar generation capacity as of mid-2021, Adani Green Energy, one of the group’s divisions, is already on par with Italy’s Enel Green as the world’s leading developer of solar energy.

At the same time as driving national infrastructure development, Adani personifies the oligarchic linkages and rentier profits generated by licensing system for infrastructure on which Modi’s growth model has heavily relied.

How to make sense of this political economy is one of the critical questions in India today. And what will be revealed by this attack on Adani?

The question of India’s new political economy was first posed in 2012 when analyst Ashish Gupta raised the alarm about bad debts at state banks. The issue was taken up by US-based economist Raghuram Rajan when he was appointed to the Reserve Bank of India in 2014. Rajan and his colleague at Chicago-Booth Luigi Zingales cast India’s problem as one of crony capitalism. Rajan as Reserve Bank Governor only until 2016.

Modi was elected in 2014 on a slate to overcome the corruption of the previous administration. But instead, the entanglement between the Gujurat business clique, headed by Adani and Ambani, and the Modi regime became ever more intense. So intense did it become that it escaped generic categories of corruption or cronyism and put in question the historic model of India’s development. As the FT noted back in 2020.

Some argue the concentration of economic power in family-run conglomerates is a way to fast-track India’s economic development, like the chaebol did for postwar South Korea. But critics say the rapid consolidation of state assets is creating monopolies and stifling competition. “Is India going to move towards the east Asian model or the Russian model? So far the tendency looks towards the latter [more] than the former,” says Rohit Chandra, assistant professor of public policy at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. “It’s not clear whether India’s concentration of capital will lead to the long-term benefit of Indian consumers.”

Rupa Subramanya writing in Nikkei Asia warned that India might be sliding from crony capitalism into something more akin to the gangster model of 1990s Russia. It takes courage for Indian journalists or activists to oppose the plans of the government-industrial and media complex. Rather than either South Korea or Russia, the other historic example that comes to mind, as the FT noted, are the Robber Barons of gilded age America.

Whether India’s industrialisation leaves it more closely resembling the US at the turn of the 20th century when the likes of oil magnate John D Rockefeller wielded vast influence, or Russia in the 1990s, Mr Adani’s voracious appetite for dealmaking and political instincts have ensured he will play a central role.

For a deep-dive on the structure of Indian political economy delve into the remarkable survey by Jairus Banaji published by the Phenomenal World at the end of 2022. Against a historical backdrop that sweeps back to independence, Banaji argues that the rise of groups like Adani signifies the fact that “the business families who formed the mainstay of industrial capitalism in the country for a whole three or four decades after Independence have either disintegrated or have been disintegrating and will soon cease to exist as coherent entities, let alone cohesive ones.”

Judged by sales Banaji sees three leading types of corporate capital in India today (whether publicly listed or privately held)

Adani clearly belongs amongst what Banaji calls the “New Capitalists” group, who as he notes are “the most fervent supporters of Prime Minister Modi. This is the case among both bigger groups (Ambanis, Adani, Sunil Mittal (Airtel), Anil Agarwal (Vedanta), the Hindujas, and Sudhir Mehta of the Torrent Group) and some smaller and less solid ones (e.g., the media tycoon Subhash Chandra who recently lost control of his flagships, with Zee Entertainment passing to Sony).”

Reading Banaji’s survey of December 2022 in light of events in January 2023 one can’t help wondering whether he does not understate the particular significance of the Adani-(Ambani)-Modi connection. Banaji’s focus, instead, is on correcting the simplistic critique of crony capitalism, which implies that India might instead enjoy a level playing-field of capitalist competition. Not only does this idealize relations between the state and capital elsewhere in the world. But, as he remarks, this side-steps the question of the “governance of capital” i.e. the relations internal to capital between management and shareholders. And, in particular, it fails to focus on the peculiarly Indian malaise of the promoters, figures like Gautam Adani, “either as a fraction of capital or as a class”. They are the key figures in the process through which old power blocs within the Indian capitalist class are dismantled and remetabolized. The new Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) of 2016 has created an arena in which business groups with easy access to capital, amongst which the Adani’s figure prominently, can snap up the assets of ruined competitors.

But what if the biggest promoter-political-capitalist of all were to come under unsustainable pressure? It is not only inequality and power imbalances that are at stake, but the financial stability of the Indian economy.

Adani’s growth has been driven by a cycle between rising equity values and corporate debt. Already In 2014 Gautam Adani boasted that his deals were “immensely bankable”. And Wall Street has really begun to take a major interest since his turn to green energy.

Source: FT

The scale of this expansion set off alarm bells already years ago:

Credit Suisse warned in a 2015 “House of Debt” report that the Adani Group was one of 10 conglomerates under “severe stress” that accounted for 12 per cent of banking sector loans. Yet the Adani Group has been able to keep raising funds, in part by borrowing from overseas lenders and pivoting to green energy. “Groups that are perceived as politically connected can still tap the banks for loans,” says Hemindra Hazari, a Mumbai-based banking analyst

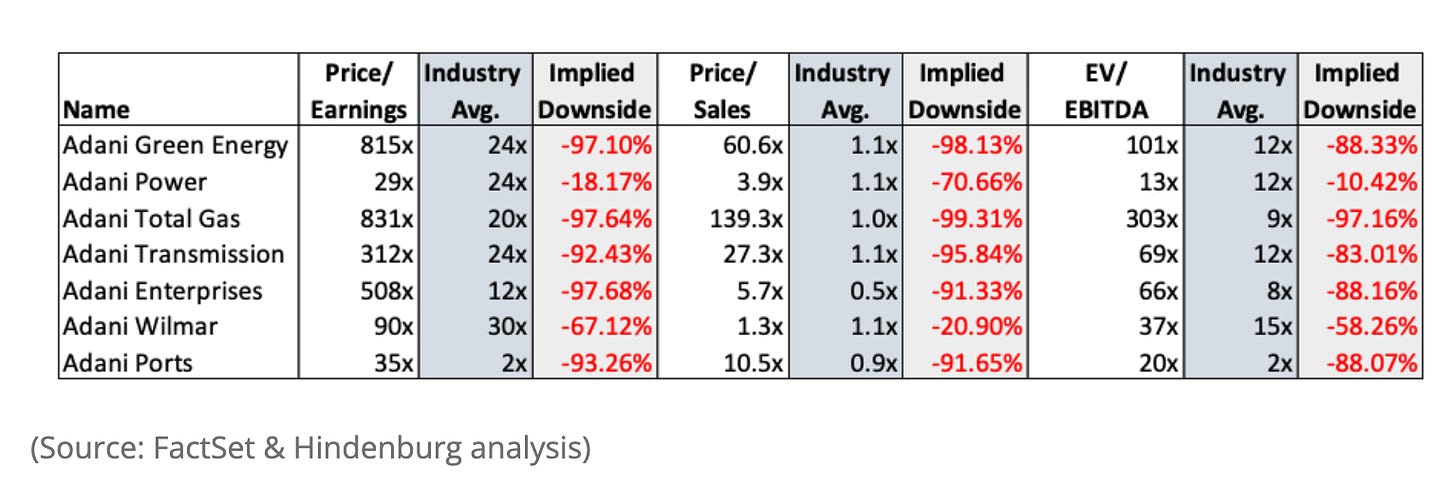

Against this backdrop, the data in the Hindenburg report are both ominous and damning.

The report alleges that the stock values of the Adani Group and thus its ability to raise debt and leverage has been wildly inflated. A valuation of the group at levels more typical of the market and the sectors that it is in, would imply a spectacular devaluation.

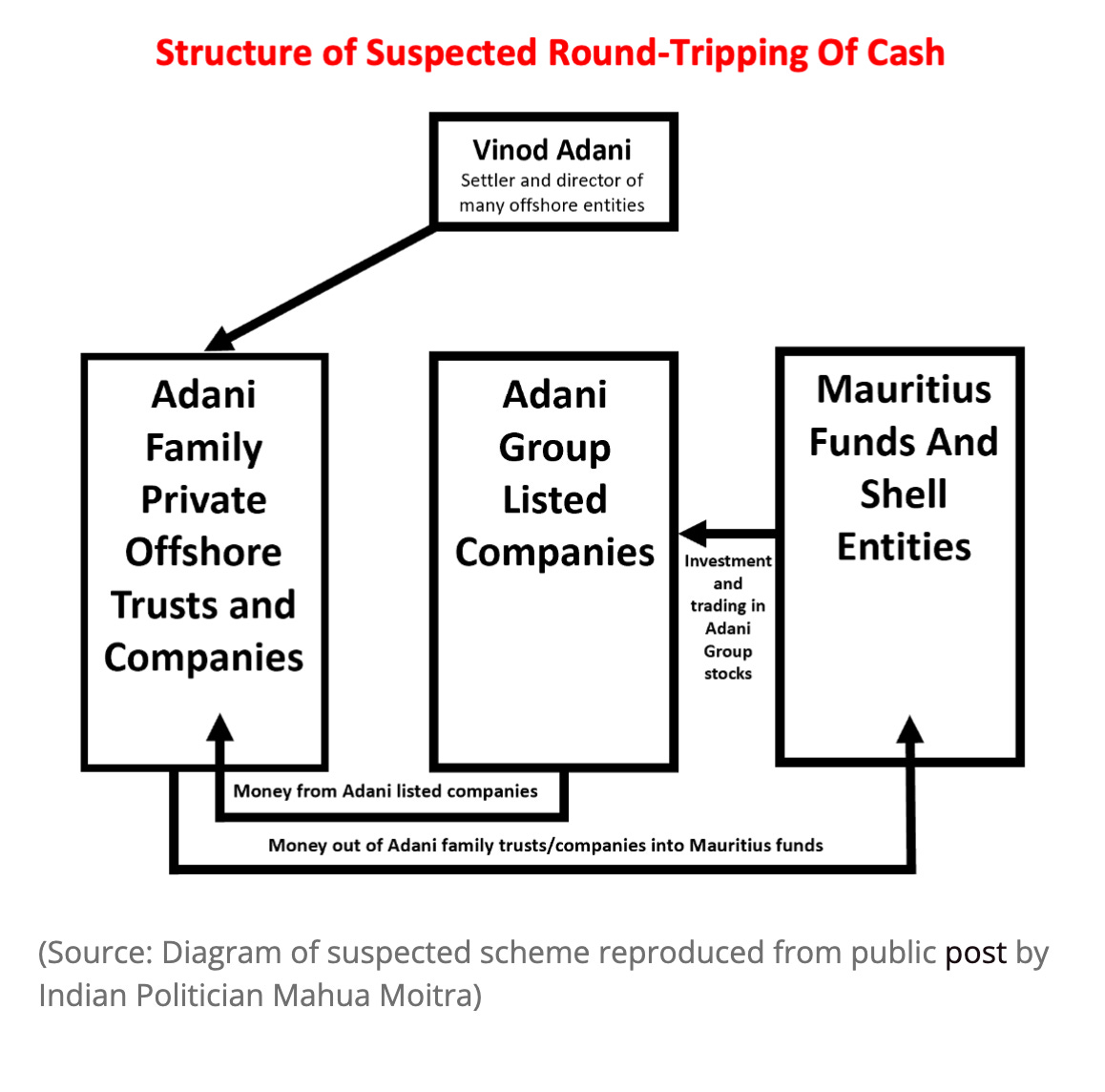

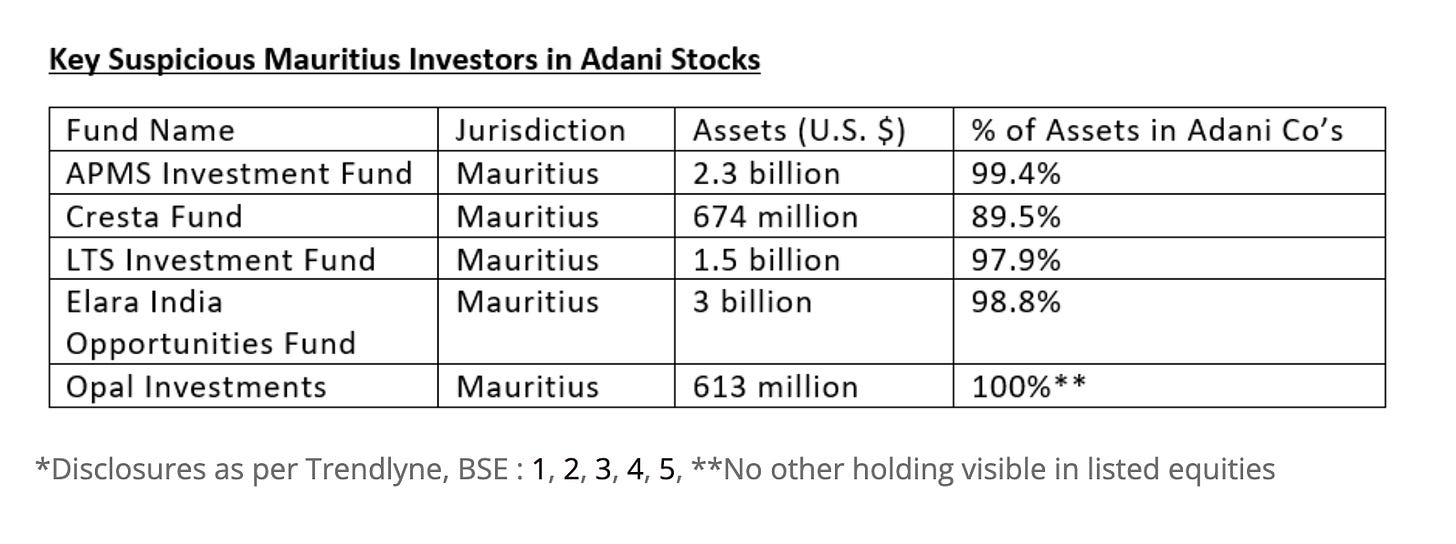

The Hindenburg report traces the mechanisms and personal networks through which stock values have been boosted by a group of circular, inside equity stakes:

Indian regulations require that a publicly listed company should have at least 25 percent outside shareholders.

Currently, 4 Adani listed companies are on the brink of India’s delisting threshold due to high disclosed promoter (insider) ownership. Adani Tranmission, Adani Enterprises, Adani Power and Adani Total Gas all have inside shareholder percentages of around 74 percent. Suspiciously large stakes in Adani group firms are held by offshore Mauritius-based letterbox firms, which are run by members of Adani entourage and appear to have no other business activity.

Were Adani to find itself in real trouble, there can be little doubt that the real anchor would be the state. Adani’s rise and the fortunes of Modi and the BJP are closely tied.

Unsurprisingly, the opposition Congress party has leapt on the Adani issue. As The Print reports, Party leader Jairam Ramesh has issued a statement.

“State-owned banks have lent twice as much to the Adani group as private banks, with 40 per cent of their lending being done by SBI,” Ramesh said. “This irresponsibility has exposed the crores of Indians who have poured their savings into LIC and SBI to financial risk.”

Congress’s standing is so weak that it is unlikely to pose a real threat. A more serious risk is that the panic spreads from Adani throughout the financial markets, forcing the Modi administration to make painful choices. As Bloomberg reports the shock and anxiety is catching especially amongst global investors who may swiftly reevaluate their weighting of Indian assets.

“The issues strike at the heart of the Indian corporate sector scene where a number of family-controlled conglomerates dominate,” said Gary Dugan, chief executive officer of the Global CIO Office. “By their very nature they are opaque, and global investors have to take on trust the issues of corporate governance.” “After last year’s stellar performance, Indian equities and any high-profile company’s shares are open to downside risk of profit-taking,”

How big the risk to the Indian banking system actually is, is disputed. The CLSA brokerage points out that much of Adani’s debt is in the form of bonds and private Indian banks are on the hook only for a small fraction of its bank borrowing. But contagion is not just a matter of facts and figures. It is a matter of overall risk appetite. Worryingly, on Friday 27 as the depth of the collapse in confidence sank in, the contagion spread to the financial sector. Shares of Indian banks and Life Insurance Corp. of India plunged on Friday.

In 2019, ahead of COVID, India was sometimes describes as a developing country suffering from rich-country banking problems. COVID displaced those concerns to the margins. With the crisis at Adani issues of financial stability come very much back to the fore. Adani’s group has been at the very forefront of the good news narrative that has yielded a series of decisive election victories for Prime Minister Modi. As Mihir Sharma points out, the Indian public is under few illusions about the extent of corruption and feather-bedding, what they expect from the likes of Adani and Ambani is delivery. But that depends on preserving at least a veneer of financial probity and stability. If the panic spreads, if there are huge losses to be absorbed, it is an open question which balance sheet will absorb the damage.

We don’t know what will come next. What we do know is that on Friday 27 January 2023 Gautam Adani suffered the worst financial blow ever experienced by an Asian billionaire. An ill-timed $2.5 billion share sale by the Adani group meant to fund capital expenditures and to pay down the debt of its various units, hangs in the balance. And much more besides. Under intense external pressure, will the Gujarat clique hold together? Will Delhi stay loyal to Adani? If it comes to a bailout will oppositional forces in India go along? What price will Modi pay? What might a dog-fight within the BJP-oligarch cabal look like?

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. I love sending out the newsletter for free to readers around the world. I’m glad you follow it. It is rewarding to write, but it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here: