Back in December last year, the collapse of FTX set off a train of thought, which was less about crypto than about the place of SBF’s arrest, the Bahamas.

Over last four years, the island chain has taken on an outsized role in my life. In the summer of 2019 Dana and I bought a tiny cottage on the outer islands chain of the Abacos that within weeks was destroyed by hurricane Dorian, the historic storm which swept through the islands between 1 and 3 September 2019.

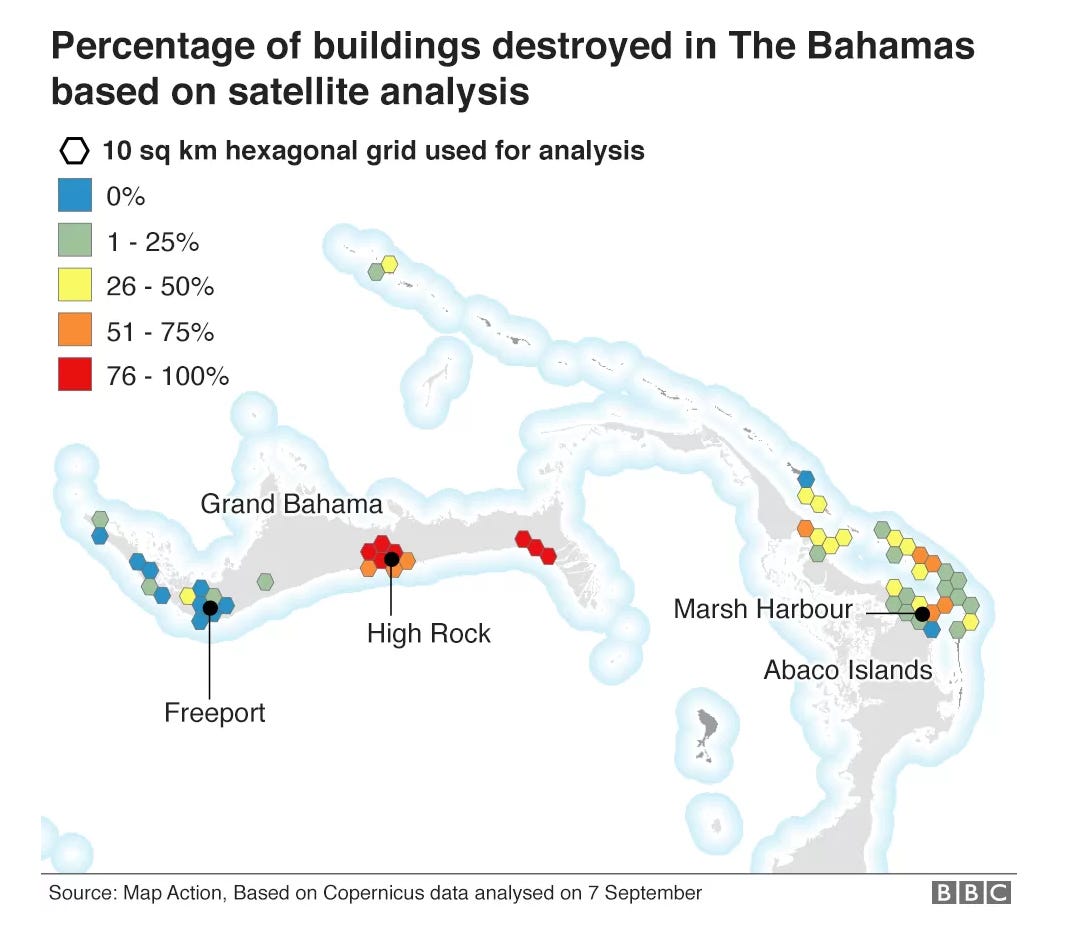

Wind speeds were sustained at more than 200 mph for several days and in an unusual and ominous development Dorian became stationary. If the storm had hit Nassau or Miami the loss of life and damage would have been immense. Our island was one of those on which 50-75 percent of buildings were destroyed.

All told the damage inflicted by Dorian in those three days came to c. 25 percent of Bahamian GDP and the Bahamas are one of the richest nations in the region.

Within a season or two the vegetation begins to recover from the lashing with salt water. Lives were put back together again. Billions of dollars flowed into reconstruction. But three years on, the scars are still clearly visible. Many ruins remain and the trauma is still live. For those who survived on the islands, all it takes is a thunder storm to revive the memory of those awful days and their prolonged and ghastly aftermath.

Since 2021, on what was left our lot, we have rebuilt a beautiful house (facebook, instagram, vrbo). The experience has been a psychodrama à la Grand Designs mixed with post-hurricane disaster capitalism in the complex economic and social setting of the greater Caribbean.

It has been a journey sustained by the beauty of the scenery, the support and love of dear friends and Dana’s indefatigable energy. It has also been an education. Along the way I’ve been trying to make sense of the experience, in medias res, so to speak. I’ve been wondering about what brought us to these islands and what kind of place they are.

Even before Dorian, feeling the force of a storm shaking what was then our tiny cottage, I wrote in a speculative fashion about the challenges to sovereignty posed by climate change. I wrote about the hurricane itself more or less as it happened. My vision then widened to the Caribbean as a whole and in particular to Haiti and US engagement there. You cannot spend time in the Bahamas with your eyes and ears open without becoming deeply interested in and concerned about Haiti. The majority of the people that built and maintain our house are from Haiti. They are in constant touch with family and friends and business connections there.

And then the FTX/SBF story added another layer. Why was FTX operating out of the Albany resort in Nassau? How did that world relate to the one that we were getting to know on the Abacos?

At one level the answer is obvious. The Bahamas are an offshore financial center. But that begs the question. Why are there offshore financial centers? And why are several of them in the Caribbean?

Over Christmas break I dug into this question in a long read for Foreign Policy.

***

In writing the Foreign Policy piece I was digesting three widely-cited historical and critical projects that have converged on the question of the geographies of capitalism and archipelago capitalism.

One was Quinn Slobodian’s illuminating discussion in Globalists of the relationship between neoliberal economics and the crisis of Empire. He traces the emergence of the original Austrian branch of neoliberalism and the founding of the Mont Pelerin society to the collapse of the Habsburg Empire in the aftermath of World War I. As he argues, Austrian economists of the 1920s saw the democratic nation-state as a threat to the free flow of resources that had been previously secured by Imperial power. A new political economy was required to encase the economy and insulate it from democratic national sovereignty.

As I show in the Foreign Policy piece, it is a logic that can be extended in interesting ways to the way in which offshore finance has found a home in the remnants of the British empire in the Caribbean.

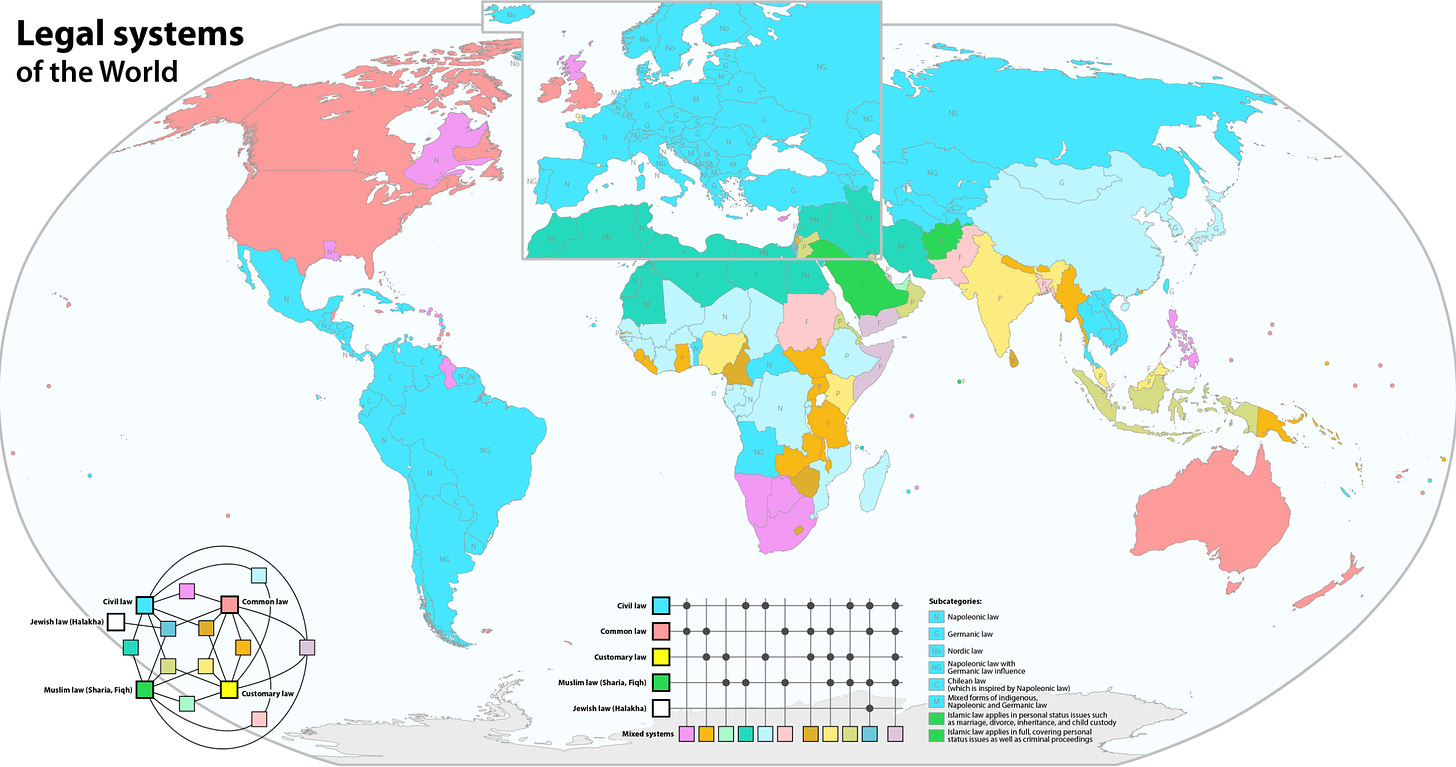

Then in The Code of Capital Katherina Pistor showed us how the English common law functions as one of the key systems worldwide for the encoding of capital. Much of the Caribbean and the wider region including, of course, the United States has inherited the English common law from the original moment of settler colonialism when the region was joined in an interconnected system of plantation slavery and long-range commerce.

Source: Wikipedia

Finally in her ongoing project on archipelago capitalism Vanessa Ogle has explored the way in which decolonization impelled the flow of funds – so-called “funk money” – around the British Empire. As she points out:

In the British Empire and the age of empire more generally, the natural state of affairs entailed legal unevenness—“lumpiness,” as Lauren Benton has characterized it.3 This world was made up of centralized nation-states, multiethnic land empires, overseas empires with their colonies, protectorates, settlements, and dominions, as well as “informal empire” with its regimes of extraterritoriality and legal pluralism. Sovereignty was often attenuated, multiplied, and layered, and authority delegated. Local administrations in overseas territories had considerable leeway in drafting company and bank laws or tax codes and accounting standards for these respective entities and sub-entities. Legal and political unevenness greatly benefited tax avoidance, and capital accumulation more generally, on a global scale.4

This offers a counterpoint to the world of nation state economic policy, “(t)he New Deal, the European welfare state, decolonization, development and modernization projects in the Third World, and the Bretton Woods system” all of which were centered on nation-state-based and government-driven projects. The offshore world by contrast offered enclaves, special economic zones, havens, relaxed regulations and minimal oversight, flags of convenience, anonymous financial and banking institutions.

***

Between the three of them Slobodian, Pistor and Ogle, offer a compelling account of the way in which the world of empire smoothed the passage to that of neoliberal globalization and why the British Empire, in particular, was a complement to the American-centered model of global capitalism after 1945.

But my question was more specific and localized. Why do certain common law jurisdictions within the patchwork left by the British empire became successful tax havens and not others? Of the British territories and former British territories in the wider Caribbean there are only four that function as offshore centers – Caymans, British Virgin Islands, Bahamas and Bermuda. Why those and not others?

One obvious explanation for the role of the Caymans, BVI and Bermuda comes straight out of the logic of Slobodian and Ogle’s work. All three have in common that they remain in the grey zones of sovereignty. Colonial elites, predominantly white, opted to remain as British overseas territories, rather than to become fully independent states. But that makes the role of the Bahamas even more interesting. In 1967, after a decade of campaigning, the colonial parliamentary system was overturned in favor of Black majority rule. And on July 10 1973 after a further round of contested campaigning, the Bahamas became fully independent. Nevertheless, the Bahamas have continued to function as a significant offshore financial center. Indeed, in the course of its half century of independence the Bahamas have become the richest Black-majority independent state in the world, as measured by gdp per capita.

That wealth, however, does not derive from offshore finance. This is one of the traps into which we fall by writing history above all through the lens of our interests in global finance. Offshore finance, though it is of great interest to Wall Street and the City of London, to regulators and campaigners in the global North, makes a relatively modest contribution to local economic activity in the Caribbean. Even in the Caymans it is not the main employer or source of income. In the Bahamas it has never been a principal source of growth or economic development. What maintains the conditions for offshore capital is a balancing act, which is dominated by a second circuit of offshore capital, the one in which, in a small way, Dana and I have been participating: the circuit of offshore property development and tourism.

In the case of the Bahamas, once you include construction and property development, this accounts for between 60 and 65 percent of GDP and a majority, even in the Caymans.

The only sector which has ever rivaled tourism and property development, was the illegal circuit of drugs from Colombia to the United States. In the 1970s and 1980s this generated a giant boom on the islands. But it also posed the greatest threat to date to their sovereignty – through the influence of the drug cartels, the damage done to Bahamian society and the intrusion of US drug-enforcement agencies. It was shut down by joint action by the Bahamian and US authorities and the shifting economics and politics of the cartels themselves, with Mexican groupings displacing the Colombians.

The mainstay of the Bahamas thus remains property development and tourism. Whereas offshore finance is truly global in reach, property development and tourism is above all an American-centered circuit. It is one which draws big money from all over the USA. Resorts like Albany where SBF holed up, or Bakers Bay on Guana are populated by US A- and B-listers. But local tourism and property development also bears the imprint of the US states closest to the Caribbean, i.e. the South – not just Miami, which helped to inspire the original hotel boom, but also Northern Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas.

That connection shaped the region in the 18th century, in the era of plantation slavery. In the 1930s money from bootlegging rum to the prohibition US paid for local white elites in Nassau to build a wall separating the black from the white town. For a great introduction to Collins Wall check out this excellent video by local historian Barbara Gibson-Wilson:

Right down to the 1960s the Bahamas was still being envisioned by its white promoters and developers as a space of segregation. That future was stopped by the fight for Black-majority rule. But the legacy persists today in the racial hierarchies of housing and the labour market. Who sleeps where and takes which ferry remains an open question on the islands. The boundaries of the racial, social and economic order are policed in an uneasy coalition of investors, homeowners and the local Bahamian authorities. In that hierarchy tens of thousands of unregistered Haitian workers occupy the lowest rung, but the permutations of race and class, ownership, residence and legal rights run all the way up and down the scale.

It is with that complex structure that the economy of offshore finance and the far larger business of land development, offshore living and large-scale resort tourism are interwoven – whether it be giant postmodern resorts like Atlantis, exclusive enclaves like Albany, or our home at the remote Southern tip of Great Guana Cay, facing out t the Atlantic and across the aquamarine waters of the lagoon known locally as “the cut”.

***

This interplay of economic system and social and racial hierarchy is of course not unique to the Caribbean. It plays out in New York City, Hong Kong or any European society. It is simply more manifest in Caribbean as it has been for more than half a millennium.

It is not a static configuration but constantly shifting. And it is that constant evolution that brings us to crypto, FTX and the Bahamas.

In Foreign Policy I argue that it was a sense of impasse in the Bahamian economic model that inspired the local political and business elite in the 2010s to embrace the promise of crypto and fintech.

It was a project that failed. Not the first and not the last.

The Bahamas are amongst things a place where “projects” go to die – plantation agriculture, sisal, pineapples, resort developments, casinos. The islands have been a theatre for one failed development project after another. Capitalism’s creative destruction plays itself out in the region with a particularly febrile dynamic. It is tempting to say that what remains, what abides is the weather, the breeze, the sun, the water. And yet, as Dorian taught us, that too can no longer be taken for granted.

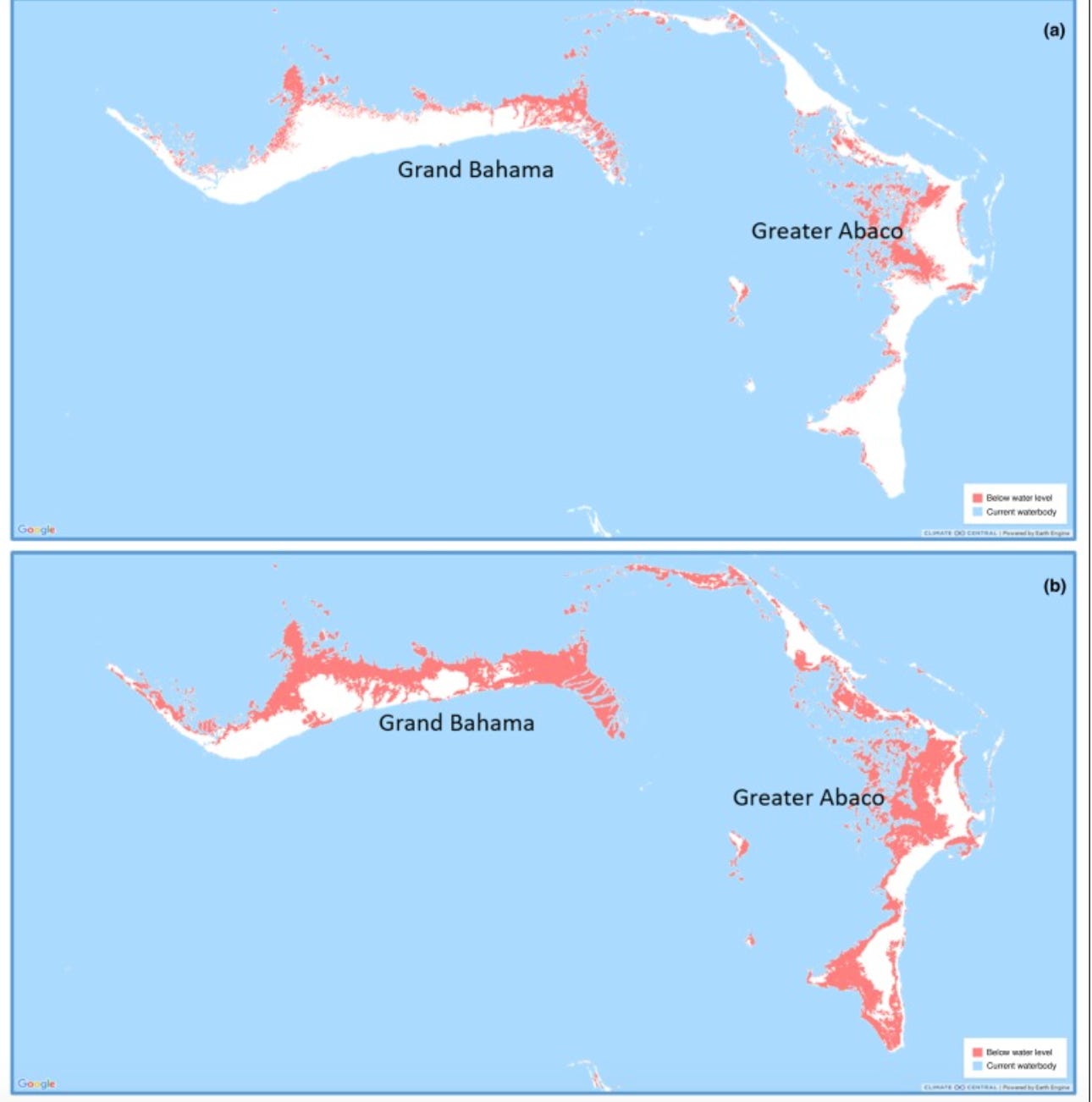

Climate change poses a mortal threat to Small Island Developing States like the Bahamas. The projections for 2100 have large parts of Grand Bahama and the Abacos under water.

Source: Martyr-Koller et al (2021)

The Foreign Policy piece ends by drawing a contrast between the approach to the climate crisis currently adopted by the governments of Barbados and the Bahamas.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. I love sending out the newsletter for free to readers around the world. I’m glad you follow it. It is rewarding to write, but it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here: