Occasionally you come across a statistical chart that casts a part of your personal history in a new light, data that places your inner life in a broader historical context. This happened to me this week when I was asked to give a talk to what is now one of the largest car companies in the world, a car-maker that was founded in South Korea in 1967, the year that I was born.

Like many boys of my generation I grew up in a world of machines – a world that was both real and imaginary, life-sized and miniaturized in the form of toys and models.

The machine that dominates our lives today, the computer, did not begin to play a role in our world – as an object of fascination in its own right or as a platform for simulating “real” machines like cars and aircraft – until the late 1970s. In my case it was the TRS-80 of 1977 on which I learned BASIC.

Before the computer it was “real” machines that seized the imagination of so many people, and particularly boys and men – diggers, trucks, cranes, ships, aircraft, spaceships, rockets, tanks, trains, bicycles, mopeds, motorbikes, go-carts, but above all it was a world of cars.

Source: Spiegel

We read about cars, and ogled them We pressed our noses against windows to spy exciting cockpit interiors. We admired speedometers that went above 200 km per hour. We played games and imagined futures of car ownership. It was a world of fantasy and fandom. It was a world of father-son dynamics.

My father was born in the late 1930s in Birmingham, hub of the UK’s Midlands manufacturing district. His father worked all his life from the office floor up, in the automotive supply chain, at Lucas Industries.

I was passionately interested in the history of the car and of motor-racing. Growing up in Heidelberg we were close to ground zero, on the route of the first long-distance car journey ever undertaken – Bertha Benz’s ride from Mannheim to Pforzheim in August 1888. We were also close to the race circuit at Hockenheim.

Though they were increasingly ubiquitous, there was still a sense in the late 1960s and early 1970s, that cars could not be taken for granted. In the countryside of Southern Europe, opening up to mass tourism at the time, horses and donkeys were still widely used for traction. But that was the experience also of a working-class kid like my father. In Birmingham after, he grew up in a street where the only motor-vehicles until the 1950s were a motorbike and a delivery van. No one could afford a car. Whereas my upper-class paternal grandfather regaled us with tales of his outings in Bugattis in the 1930s, and beat his cars to bits, my paternal grandfather treated his 1960s vintage gold metallic Vauxhall Viva like it was a crown jewel and liked to take the family for “a drive”. No destination. Just for a drive. In the early 1970s that was, for their generation, still a precious and exciting novelty.

It was not all celebration. Very often, cars of that era did not work. Keeping them on the road was a communal effort. And the transformations they had brought to everyday life was not simply welcomed. Dinner tables divided over the havoc wrought by the car in European and American cities and controversial debates about pedestrianization. As the casualties of early motorization – motorization without seat belts or airbags or bike lanes – piled up, you were lucky if you did not know anyone who knew someone who had been maimed or killed. One of my tutors, a scholarship winning maths genius, was hit by a speeding car and never recovered, reduced to a suicidal, wheel-chair bound shadow of his former self.

Peacetime road fatalities in the UK peaked in 1966 at a rate of 22 deaths per day.

Source: Wikipedia

Professionally, I went on to write and think a fair amount about mass production and motorization in Nazi Germany.

So, after all of this, the statistical chart that I encountered this week should not have come as the surprise. But there they were: The numbers for the global production of cars in the 20th century.

Source: OICA

And the thing that struck me was the surge between the early 1950s and the 1980s. Two times, between the early 1950s and the early 1960s, and between the 1960s and the 1980s, global car production doubled, going from 10 million to 40 million units per annum. What I realized more starkly than I ever have before is the fact that the period in which my parents came of age and I grew up was in the midst of a revolutionary transformation of industrial production, transport and social life.

Furthermore, not only did global production quadruple, but almost all of the growth took place outside the United States, the original hub for the mass production of cars in the interwar period. In 1950, 75 percent of all cars produced worldwide were produced in the United States. But over the subsequent decades US production remained largely unchanged, whereas that of Europe and Japan surged. By 1980 the US share of global production had fallen to 20 percent and Japan was making more cars than the USA.

These numbers are compiled on a national basis, which is interesting from the point of view of the geography of production. But since motor car manufacturers operated globally, the reach of Ford, GM and Chrysler extended across the world. My grandfather’s Vauxhall was a General Motors car. In a future post about the global car industry and the IRA I will analyse some data on market share broken down by the big corporate blocks.

In any case, however you count it, what is clear is that the expansion in global car production took place between 1945 and the 1990s not within the territory of the US itself, or even North America, but within the ambit of the US hegemonic sphere, in Europe, in Japan and South Korea.

Of course, cars were produced in the Soviet bloc as well, but on a much smaller scale and often under license from Western firms, notably Italy’s FIAT. The car and thus petrol-based industrial and urban form was a specialty of the capitalist world. It was not until the 1990s that this became a truly global experience. In China the automotive revolution is still unfolding. In India and the rest of the low-income world is has barely begun.

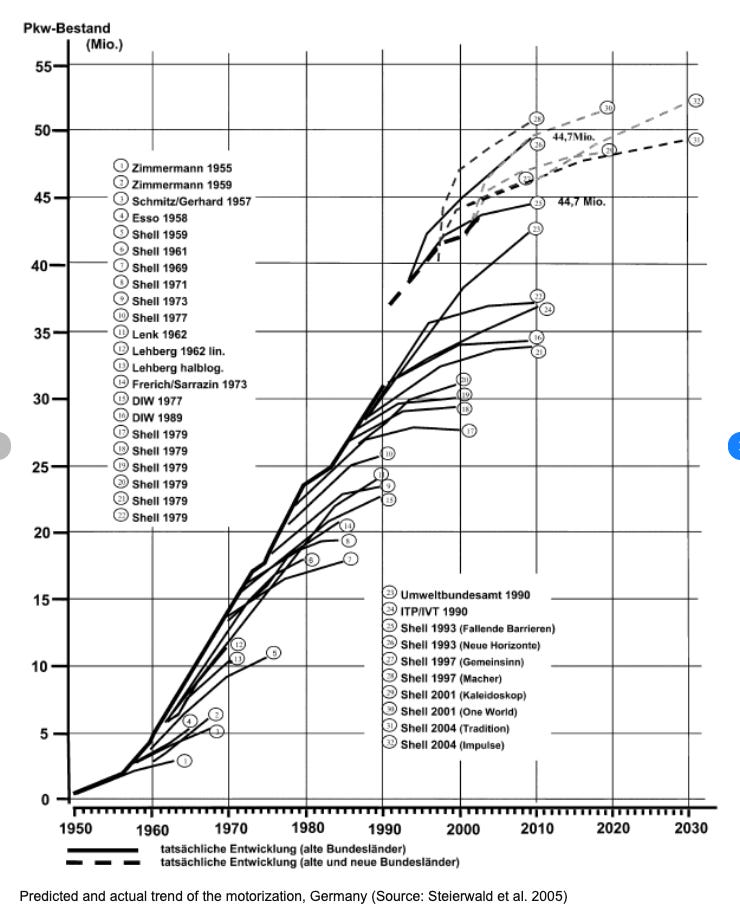

The impact of motorization on Europe in the postwar period was truly dramatic. In Germany the stock of cars went from only 5 million in 1960 to almost five times that twenty years later. Forecasters consistently failed to keep up.

Source: Steierwald et al

The car culture which I grew up in was fully internal to this “Fordist dream”.

But Fordism was always accompanied by its critique. This took high-brow form in the writing of Marxists such as Antonio Gramsci. It took practical form in the prevalence of wild-cat strikes in many car plants around the world. If you followed the news in the 1960s and 1970s you knew the location of Ford’s car factories in Dagenham and Halewood or Fiat’s giant plant at Mirafiori from the strike reports.

Critiques of alienation on the assembly line circulated alongside the triumphalist narrative of abundance. By the early 1970s the critiques themselves had become their own cliché. As a kid I remember being taken to see Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times in flea pit art house cinemas by a left-wing child minder. Understanding the ills of mass production was part of a liberal education.

And it was out of that common sense critique that the fascinating debates emerged in the 1980s about flexible specialization and smart alternatives to mass production -arguably the last major debate about industrial production before the conversation of the last decade that focuses on the energy transition and “hard to abate sectors”.

But then, at some point in the 1980s, the excitement around motorization let up. Perhaps it was a matter of growing-up. The generations raised on car fever entered adulthood and middle-age. For many of us, perhaps most of us, our priorities changed. Jn the 1990s the East Europeans were excited about Western cars, but that was a marker of their backwardness. You still enjoyed Top Gear, and marveled at the improvements in performance and reliability, that measured against the standards of the 1970s were simply astonishing, but it was no longer the passion or the drama it had once been, when the presses stood still and VW replaced Hitler’s Beetle with the hatchback Golf. No doubt it was an effect of saturation. The take-off was over. There were only so many cars you could sensibly drive and park, only so many GTI updates that you could get really excited about.

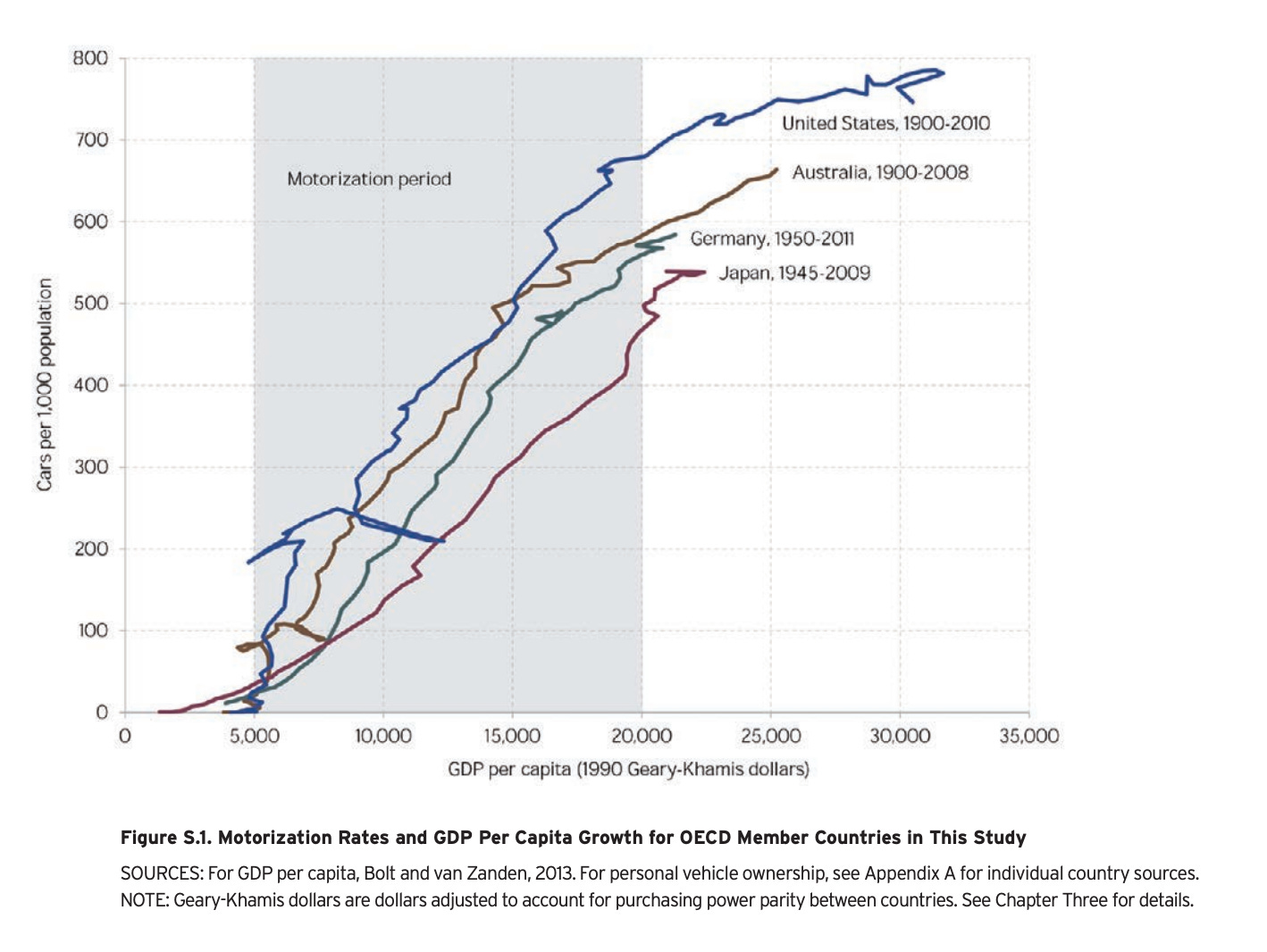

Source: RAND

Cars were no longer revolutionary. They were the status quo. Indeed, much of car culture took on a somewhat defensive attitude, resisting tighter regulations, higher parking fees and environmental regulation.

It is this arc, which I now read as both a personal and more general history – a gendered and generational experience – it is this arc that leaves me so fascinated that with the EV revolution and the Inflation Reduction Act, we are once again talking not just about the Biden administration, China and the climate, but about cars and how we make them. And by way of the work of Chuck Sabel, David Victor and others, the conversation about production that began in the 1970s and 1980s has at last resumed.

More soon in Chartbooks to come.

***

I love putting out the newsletter for free to thousands of readers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options.

Several times per week, paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

There are three subscription models:

- The annual subscription: $50 annually

- The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.

- Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.