Though the news from the frontline may be good for Ukraine. As the summer comes to a close, its economic situation is increasingly alarming. The Russian invasion dealt a devastating blow to Ukraine’s economy, its public finances are in free fall, inflation is surging and millions are threatened with misery and deprivation. Unless Ukraine’s allies step up their financial assistance, there is every reason to fear both a social and a political a crisis on the home front, which will massively compound Kyiv’s difficulties in continuing the war regardless of its progress on the battlefield.

This bleak news is driven home by a joint report compiled by the government of Ukraine, the World Bank and European Commission.

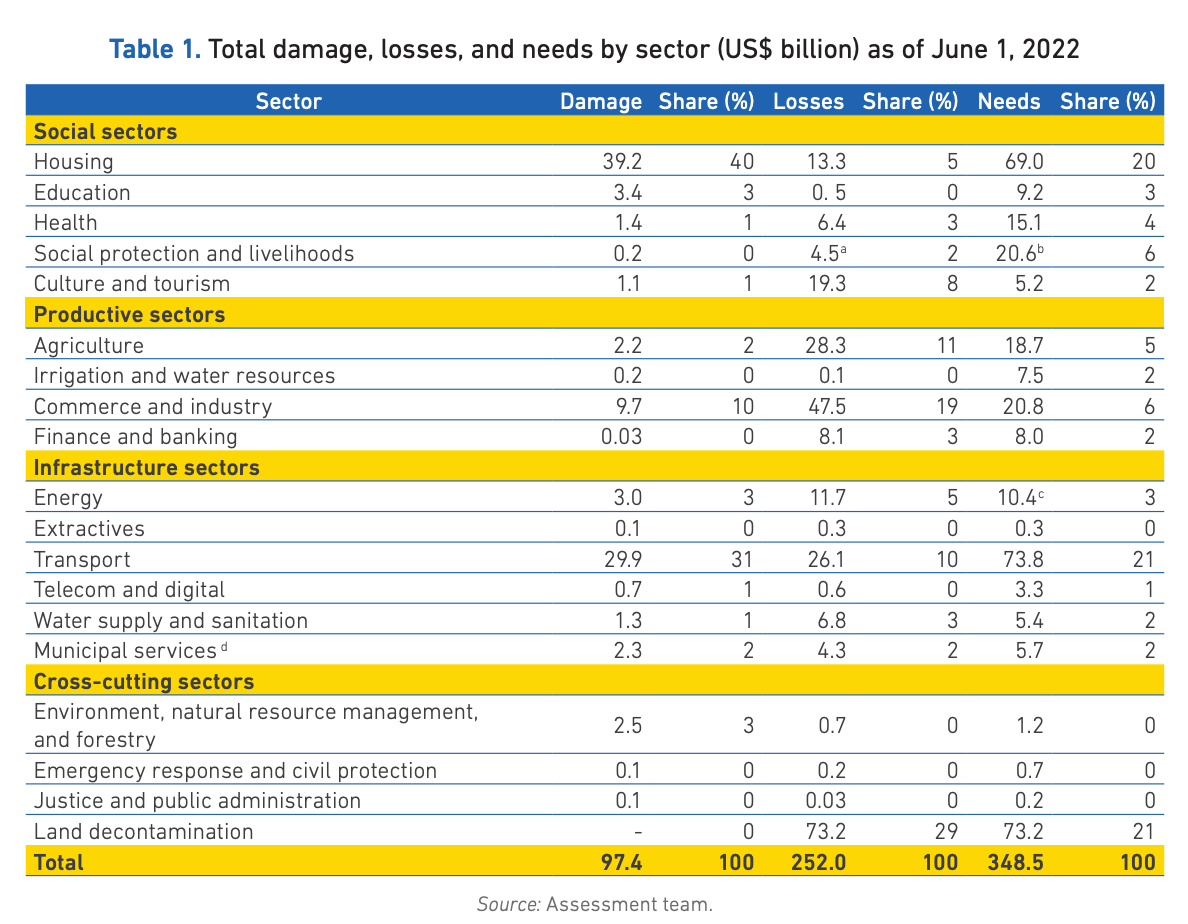

The main purpose of the Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment report is to document the financial needs of long-term reconstruction. To this end the report contains an impressive compilation of tables showing damage to housing, infrastructure and the need for decontamination.

All told the bill for recovery and reconstruction comes to $104 bn in immediate and short-term spending and $243 bn over the longer term.

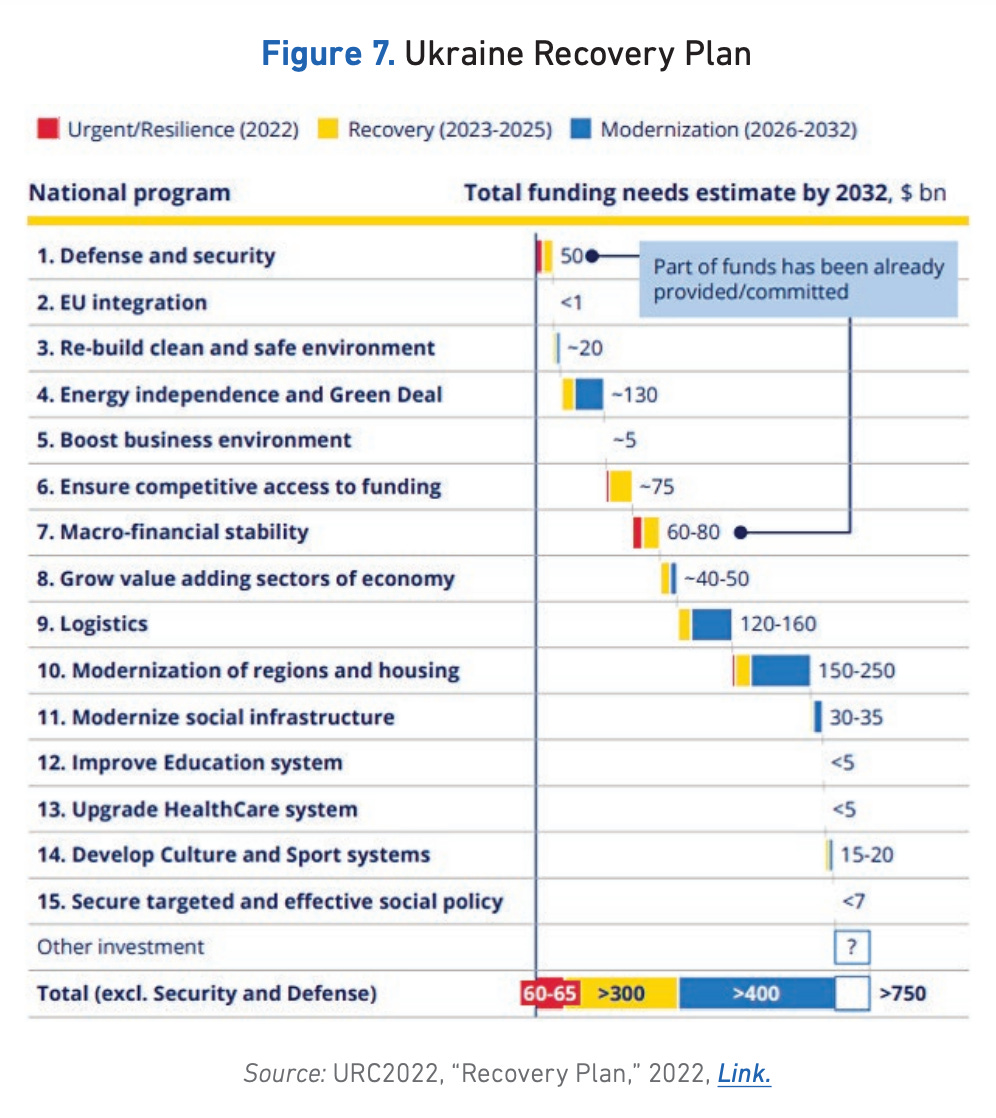

As laid out at the Lugano reconstruction conference in July, Kyiv has a recovery plan that stretches to 2032 and involves spending on reconstruction and modernization totaling $750 billion.

All of this long-term planning, however, has a ghostly aspect given the desperate economic and social situation facing Ukraine, not by 2032, or 2025, but over the coming weeks and months.

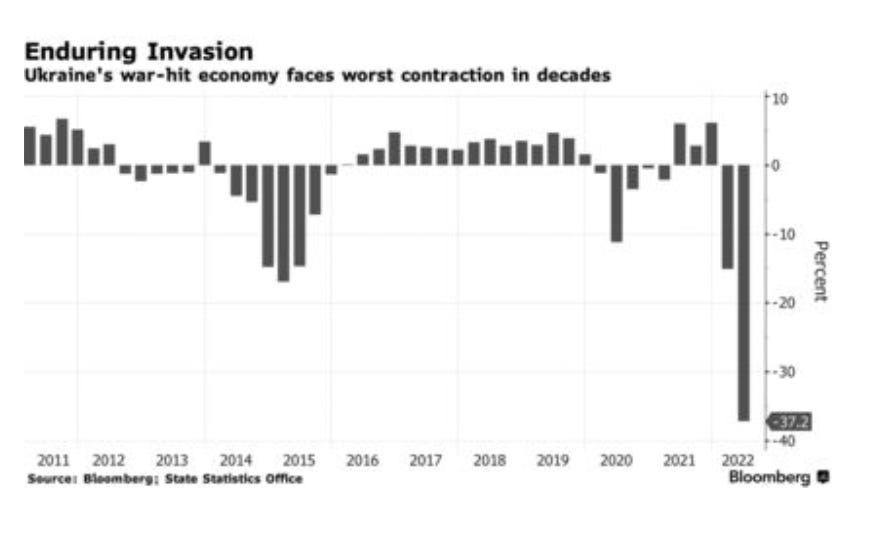

The hit to Ukraine’s economy in the spring was devastating. In March, the Russian attack engulfed 10 oblasts and the city of Kyiv, which together account for more than 55% of prewar GDP. Today, the fighting continues in regions which account for c. 30% of prewar GDP.

Under the immediate impact of Russia’s assault, in the first quarter of 2022 Ukraine’s GDP shrank by 15.1 percent year over year (YoY), wtih a gigantic 45 percent fall in March. In the second quarter, the contraction on an annualized basis was measured at 37 percent. This is far worse than the shock suffered by Ukraine in 2014-2015. With some signs of recovery in August, Kyiv is now guestimating that the contraction for the year as a whole will be in the order of 33 percent.

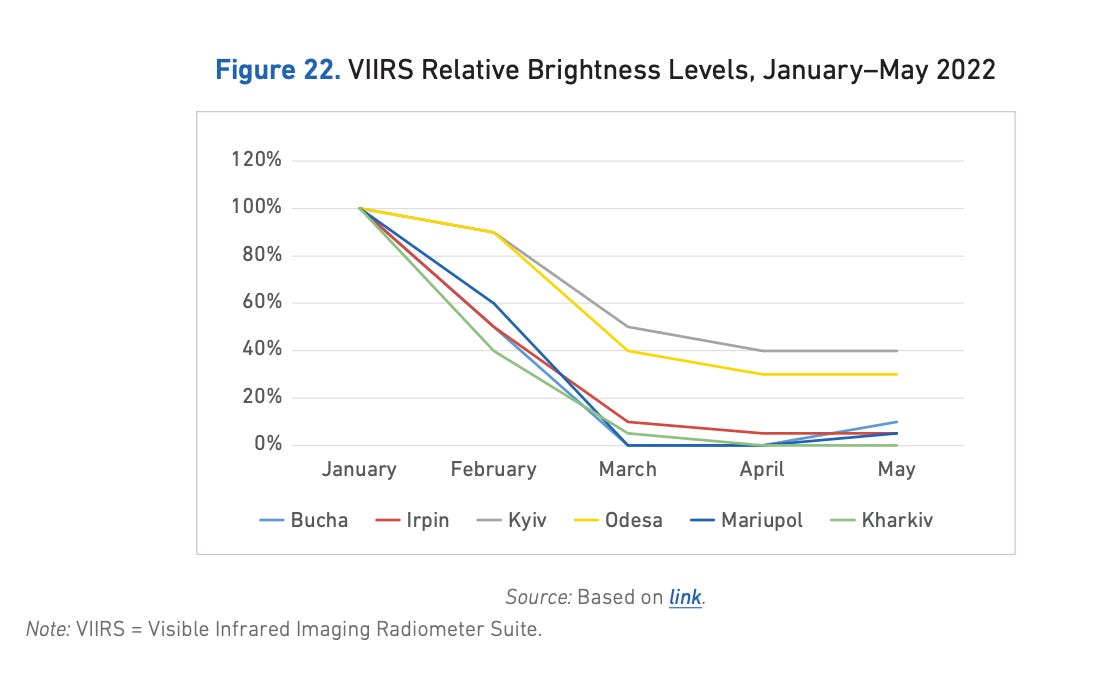

These GDP figures are dramatic. But they are also rather abstract. A more concrete way to track the level of economic activity is to monitor night-time illumination. All over Ukraine in the spring of 2022 the lights went out.

This is normally an excellent indicator of the overall level of economic activity. But as the RDNA report notes, there are things to bear in mind when monitoring illumination in wartime.

While in this case nightlight brightness is not a direct indicator of access to electricity services (since many citizens hide in their basements at night), in some cities it remains an indication of the loss of access to electricity. As shown in Figure 22, streetlights completely disappeared in most of Bucha and Irpin during March and April. In Kyiv, the decline was more gradual and has remained stable after the end April.

Another way to bring home the significance of the GDP numbers, is to examine levels of poverty.

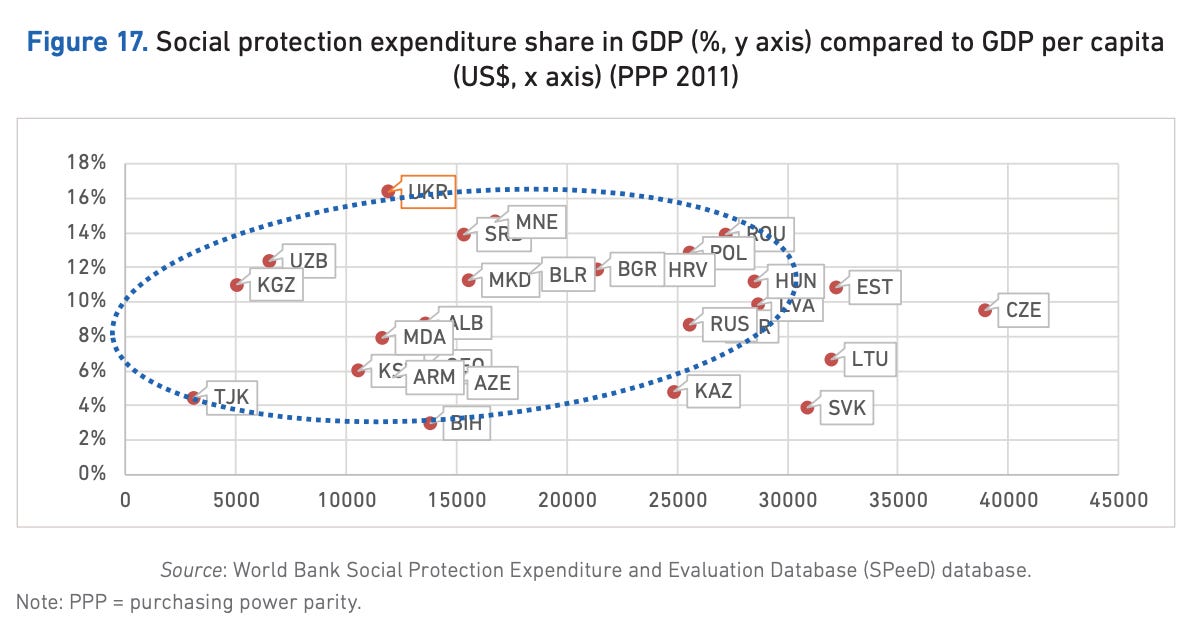

Prewar, Ukraine was a middle-income country with a poor track record of growth. But it was also a post-Soviet society with an unusually large welfare network. In Ukraine, a quarter of the population receives old-age pensions, which are a key safety net.

As a result of this extensive welfare network, severe poverty below US$5.5 per person per day was rare. Under the impact of the war, the share of Ukrainians falling below that poverty line is expected to increase tenfold and reach at least 21 percent in 2022; war-affected regions are expected to experience much higher poverty rates. In Khersonska oblast, which is currently at the heart of fighting, food prices have surged by 62 percent resulting in a spiking poverty rate.

For a large part of Ukraine’s population of 44 million, the war has upended normal life:

One-third of Ukrainians have been displaced by the war. Over 6.8 million Ukrainian residents have left the country, a large majority of them women and children.4 An estimated 6.6 million people are internally displaced—fewer than in the previous month5 —with many individuals displaced more than once since leaving their homes of origin.6 According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the humanitarian situation is deteriorating rapidly, as access to critical services such as clean water, food, sanitation, and electricity declines, and 17.7 million people are left in need of humanitarian assistance

The social crisis is so severe, because of the inability of the majority of the internally displaced refugees to support themselves.

To address this crisis, Ukraine’s needs a capable government apparatus. It has a dense network of social provision. But those agencies, networks and institutions need funding and that is in jeopardy.

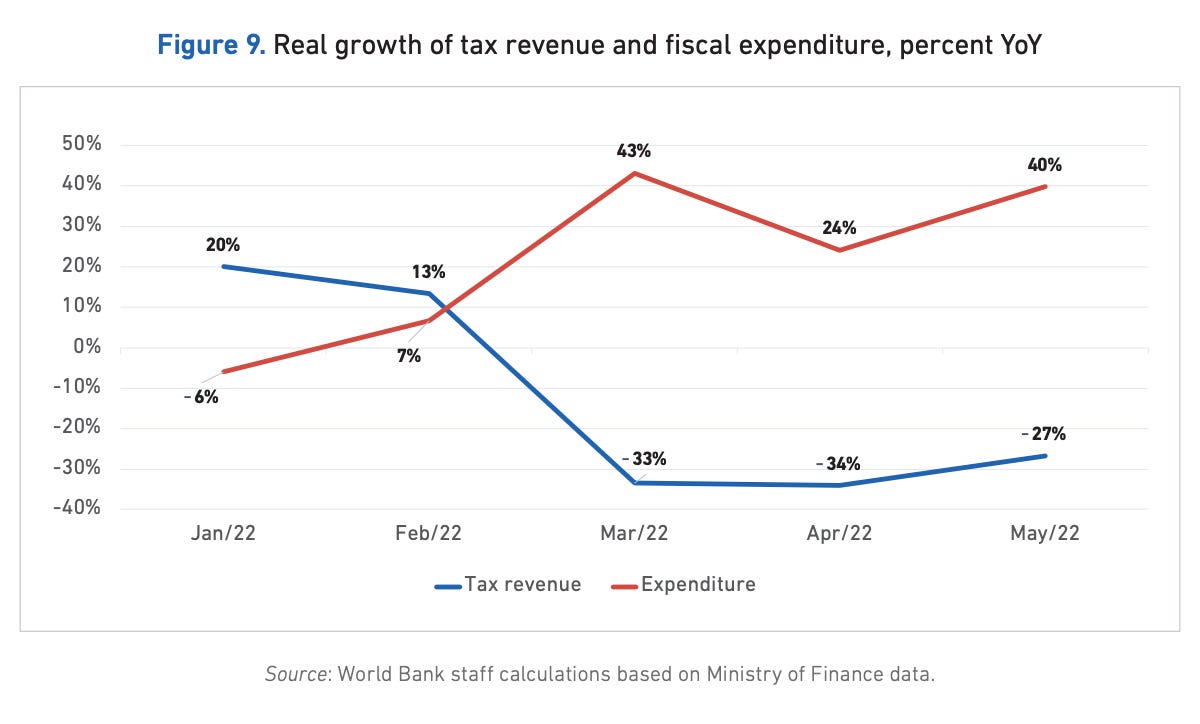

Since the beginning of the war, tax revenue collection has deteriorated significantly, while public expenditure has increased sharply.

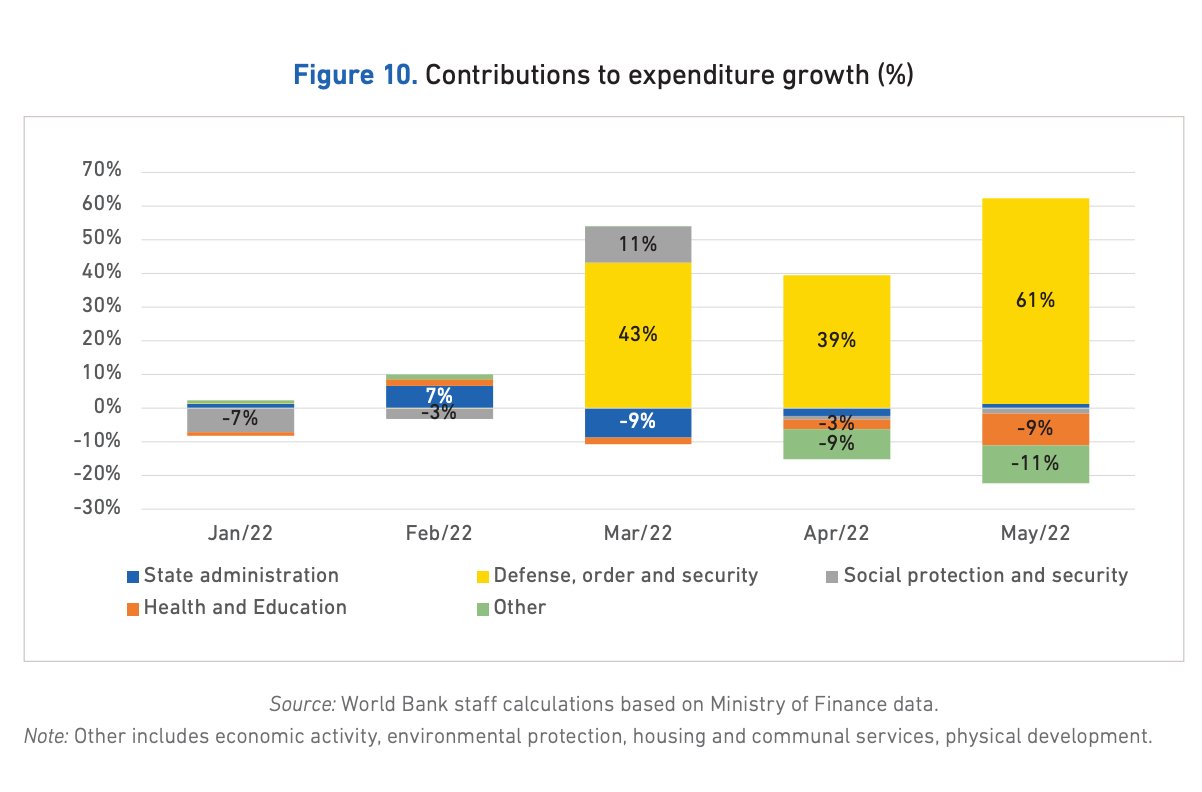

Since the beginning of the war, as military spending surged by 4.5 times, Kyiv has struggled to slash non-military spending.

Non-essential current expenditures have been cut 78 percent YoY. Far from engaging in large-scale reconstruction, capital spending has been cut back by 61 percent YoY. But there is a limit to how far austerity can be carried in wartime. Between March and May, Ukraine’s public spending on wages and salaries surged, including for emergency medical personnel and first responders. Transfers and social protection spending increased, as did procurement of goods and services, to pay for basic recovery work. All told – despite the cuts in non-priority areas – surging spending and falling tax revenues have opened a nonmilitary fiscal need of over US$15 billion for the second half of 2022. This figure takes account of Kyiv’s efforts to reduce its debt service by rolling over domestic debt and a two-year deferral on external debt amortization. Allowing for military spending and current recovery needs, Ukraine’s total fiscal financing needs may reach US$28.8 billion in the second half of 2022 (around US$4.8 billion per month).

To cover some of this funding shortfall, the National Bank has stepped in to monetize the deficit. As of the end of June the National Bank had monetized over US$7.7 billion in fiscal needs.

That paid the bills but it also helped to stoke a surge in inflation. In August inflation in Ukraine reached 23 percent year on year, more than double the rate in February. By the end of the year, the central bank warns that inflation may reach 30 percent.

If this continues the outlook is disastrous.

In a scenario of continued deficit monetization, the poverty rate is expected to climb to 34 percent by the end of 2022—a level not seen since the early 2000s—as rising inflation erodes the purchasing power of low- and middle-income households. Going forward, if the extent of monetization is limited to avoid excessive inflation, sweeping expenditure cuts will be needed and will affect the most vulnerable segments of Ukrainian society. Under this scenario of austerity, poverty rates are projected to further increase to over 40 percent in 2022 and 58 percent by 2023. In this worst-case scenario, an additional 18 million Ukrainians would fall below the poverty line.

The National Bank is struggling to control inflation. It has raised interest rates to 25 percent. It would like ideally to absorb as much purchasing power as possible into stable, government war debt. That puts pressure on the government to offer attractive interest rates. But, for fear of further burdening the budget, Zelensky’s government is resisting an increase in bond coupon. If interest rates on war bonds are too low, however, they will not attract buyers, which in turn forces the central bank to finance the war effort itself.

Given the scale of the financial pressure it is under, it is hardly surprising that Kyiv is appealing for help from outside. Last week it asked for an immediate package of international financial support totaling $17 billion.

So far the international community has been providing c. $1.5bn a month to support Ukraine’s budgetary needs, which is significant, but far short of Kyiv’s needs. Pledges to date extend no further than the end of 2022, with no firm commitments for 2023. The EU signed up to a notional total of €9bn in budgetary support in May, but only about €1bn has been disbursed. With Kyiv running deficits of $5bn a month Von der Leyen said on Friday that €5bn from the EU was “in the pipeline”.

The urgency of those funding needs is compounded by the seasonal outlook. With the summer having drawn to a close, Ukraine now faces falling temperatures. As the FT reports, “average temperatures in Ukraine typically fall from 20C in summer to minus 3C in winter, with an average of minus 7C in some regions, according to the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia.” As Arup Banerji, the World Bank’s regional director for eastern Europe, noted:

the bank was “terribly concerned” about the arrival of winter. “The damage that Ukraine has suffered has been just staggering,” said Banerji. “Ukraine’s winter season starts on October 15 and can be really harsh. This could be quite devastating given that many houses have windows and doors missing and there are so many internally displaced people.”

A population of millions, facing a freezing winter with windows and doors blown out, is a grim prospect indeed. Without a dramatic step up in international financial assistance, Ukraine will face a tragic choice between continuing the war at full intensity and risking a social and economic crisis that will destabilize the home front. If Kyiv finds itself in that impasse, the risk is that the highly technical tensions that are currently visible over interest rate policy between the central bank and the national government will widen into deeper political divides over the management of the war effort. That would put in jeopardy the political consolidation that has been one of Ukraine’s most remarkable achievements in this terrible ordeal.