We are at a strange juncture.

The symptoms seem familiar. We have experienced months of rising inflation and are living through something akin to an inflation scare.

Interesting. According to the UMich Survey, there's been a huge surge in people saying they've seen unfavorable news stories about what's going on with inflation.

— Joe Weisenthal (@TheStalwart) March 18, 2022

Whereas there's been a big drop in news stories about progress made in the labor market. pic.twitter.com/5IOLyefMWI

There is war involving Russia, a major energy exporter. The war in Ukraine compounds an existing crisis in the global energy economy. There is even talk of oil boycotts.

For some commentators the shades of the 1970s are irresistible. Larry Summers is the most notable example of this tendency.

But the retrospective tendency is not confined to the centrist mainstream. Without drawing false equivalences, some of the left Keynesian discourse on inflation also has a “back to the future” feel. The price controls debate is after all a deliberately historicizing provocation. The idea is as scandalous as is it is to mainstream economists because it smacks of a return to what they regard as the failed experiments of half a century ago.

Rather than back to the future, the left position is better described as “back to an alternative future”.

Given the actual macroeconomic track record in the 1970s and 1980s it surely ought to be mysterious why anyone would take the record of Paul Volcker and the costly monetarist experiments of the era as a success rather than a brutish demonstration of the effect of a sudden tightening of the dollar system.

Nevertheless, homage to Volcker is the charade that Fed chair Jerome Powell enacted in front of Congress last week. As Colby Smith reported for the FT.

Testifying before Congress earlier this month, Jay Powell was asked if the Federal Reserve was prepared to “do what it takes” to get inflation back under control — and if necessary, follow in the footsteps of his venerated predecessor, Paul Volcker, who regained price stability “at all costs”. Calling the late Volcker “the greatest economic public servant of the era”, Powell responded: “I hope history will record that the answer to your question is yes.”

As less credulous observers noted, the Fed’s actions speak louder than words and they seem to suggest the very opposite of any Volckerian inclinations.

Powell struck an optimistic note at a press conference on Wednesday, saying the sheer strength of the US economy meant it could “flourish” in the face of less accommodative monetary policy. Economists have welcomed Powell’s embrace of a much more aggressive policy approach, compared to the gradual pace signalled just three months ago. They warned, however, that the amount of monetary tightening potentially needed to quell inflation may produce much more economic pain than the Fed is willing to admit.

The real novelty in the current situation is this stark discrepancy between discourse and practice.

Whilst the rhetoric on all sides is redolent of the 1970s and 1980s and the need to make tough choices, America’s central bank. The Fed has been slow to raise rates and when it did, it chose to raise them by no more than a quarter percentage point. This week it rejected the idea of sending a dramatic signal by making a half percentage point move.

Much as Larry Summers demands that interest rates must be hiked faster than inflation, the Fed is holding back. It it is refusing to add to the drama of the situation by delivering a true monetary shock.

To its critics, Powell’s Fed has simply lost the plot. It is “behind the curve” and incoherent. As John Authers pointed out in a typical sharp-eyed piece:

The (most recent) inflation estimates (by the Fed) are, obviously, much higher. Perhaps more shockingly, they are all over the place. This year has nine months to run, and yet the spread of estimates for inflation at the end of it covers almost two percentage points. There is no consensus. That is alarming, and prompted some to fear that the Fed was admitting it didn’t know what was going on.

Then there’s the question of the Fed’s internal inconsistency. The FOMC allegedly believes that inflation will come back down to 2% for the long term, without a recession and with barely an increase in unemployment. On top of that, the committee also thinks that the fed funds rate will top out for the long term at 2.4%. In the decade that the Fed has been publishing the dots, this is the lowest projection for long-term rates on record. Somehow it has actually dropped 10 basis points since December, despite rocket-like inflation, omicron, and a land war in Europe:

But if the Fed, according to the hawks, has lost the plot, the question is why? In the standard model of policy-failure in the 1970s the underlying logic derives from a balance of social forces – organized labour v. capital. That is hardly a plausible story today.

One can hardly claim that Powell’s Fed is under pressure from powerful social forces, other than perhaps the stock market. Last fall the largest industrial dispute across the workplaces of the United States was the graduate strike on the campus of Columbia University. We are not actually back in the 1970s.

In any case, whatever the reason for its complacency, the cardinal sin is not to have listened to the hawks like Larry Summers.

The Fed’s defenders point to the fact that it is not only the Fed that is complacent. Bond markets don’t believe in a scenario of runaway inflation or violent recession either. On this view, the markets and the Fed are muddling through an unprecedented situation – COVID, supply chain difficulties, energy shock, Ukraine – as best theyt can. If this takes a bit of hypocritical mood music about Paul Volcker, that is a small price to play.

Finally, on a third reading, the Fed is acting entirely consistently, but it has adopted a model of the American economy which denies the idea that there is a strong linkage between the current inflation and the underlying state of the American economy.

As the FT remarks:

The Fed’s recent forecasts are notable for the central bank’s apparent belief that it can painlessly reduce inflation. The central bank predicts that the unemployment rate will fall further to 3.5 per cent and then remain there, even as rates rise from the current 0.5 per cent to an expected 2.8 per cent by 2023. Powell has previously expressed admiration for his predecessor Paul Volcker’s choices in the late 1970s to raise rates aggressively even in the face of mass joblessness; the latest forecasts deny such trade-offs even exist.

At the end of the last year Jerome Powell officially buried any talk of “transitory” inflation i.e. inflation induced by temporary and abnormal COVID-related shocks. And yet the modesty of the Fed’s moves on interest rates suggest that the Fed still believes that they are a not the best weapon with which to moderate price increases. As Ramesh Ponnuru argues, the theory seems to be that the inflation we are experiencing is simply not best addressed by monetary means.

As Joe Weisenthal points, there are a variety of structural factors other than energy prices that are helping to drive inflation.

The @neelkashkari piece on why inflation has stayed hot longer than he expected is a good read.

— Joe Weisenthal (@TheStalwart) March 18, 2022

IMO the persistence of the shift-to-goods spending is an important factor driving inflation, and can't simply be attributed to overly-stimulative policy.https://t.co/bxCGlui55j pic.twitter.com/fCGnqVYU7x

These three interpretations of the Fed are stereotypes.

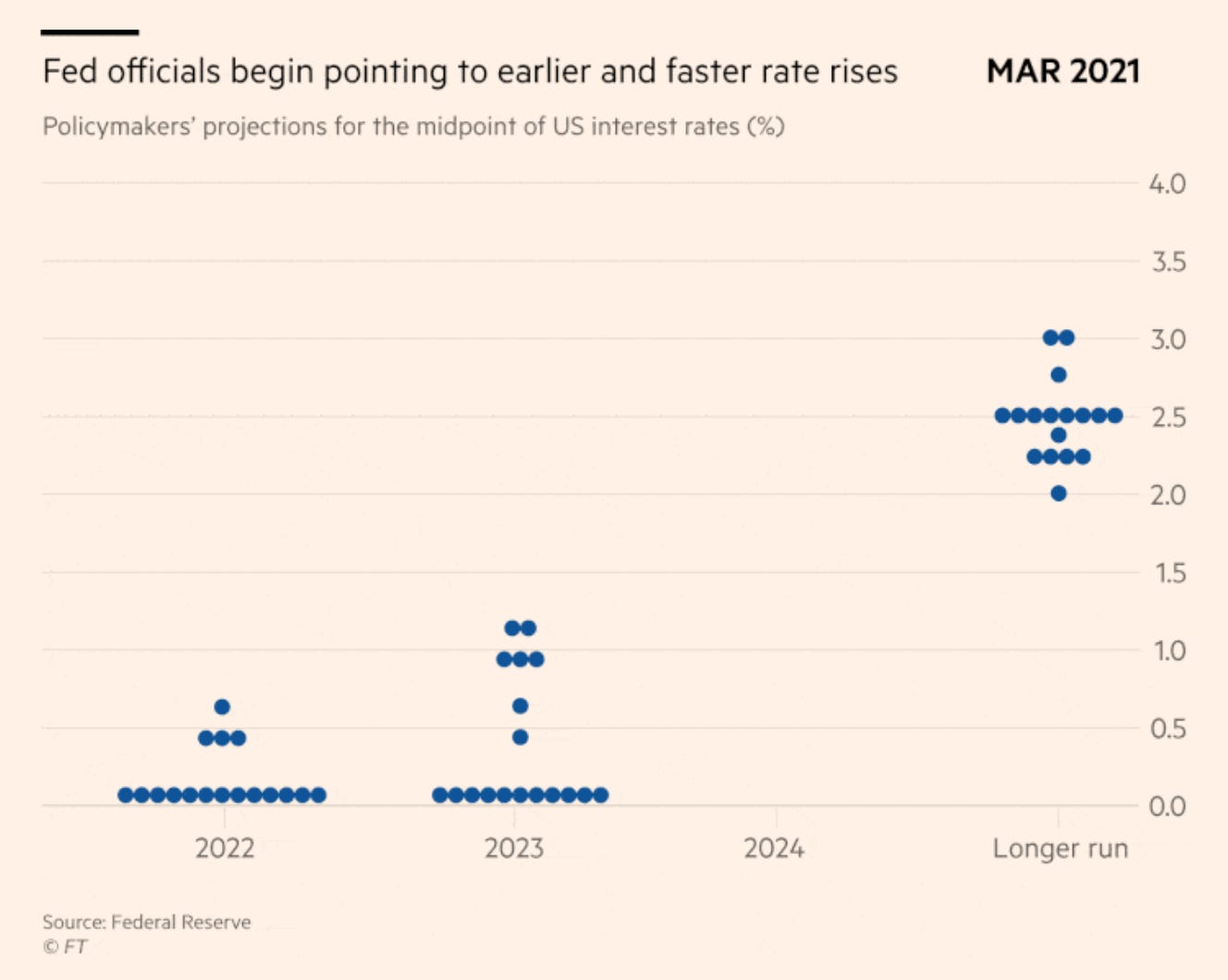

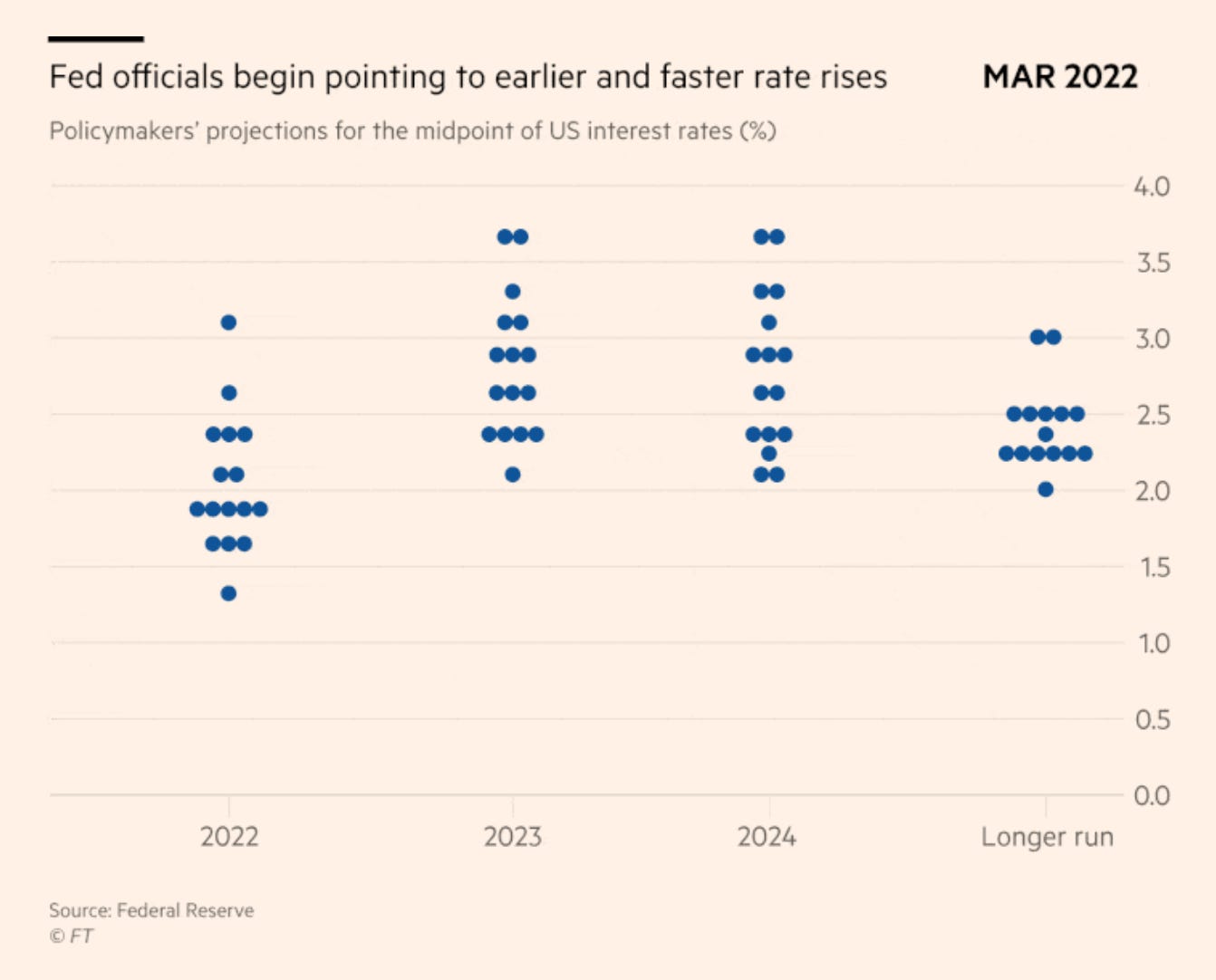

In fact the Fed is not reconciled with itself. The critics are not wrong to point to incoherence. With regard to the FOMC’s estimates of future interest rates there has been a truly spectacular shift over 12 months.

Source: FT

What are we to call this new moment? Some will no doubt want to denounce it as the “great complacency”. Might it simply be that the politics of the great moderation die hard. Rather than confusion or complacency, might the Fed actually be attempting something rather ambitious?

On either the second reading (muddling through) or the third (team transitory), the Fed’s aim seems to be to pull off something very difficult: a soft landing in heavy weather.

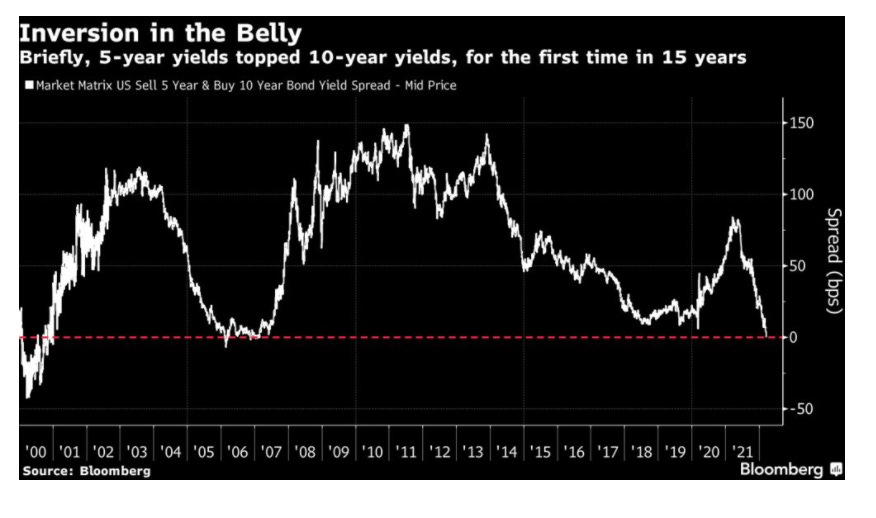

One is attempted to say that pulling off such a landing it is not just difficult but hedged by risks. What Summers and co worry about is a painful recession that may be necessary to end inflation. As Authers points out, the yield curve has already inverted.

In the wake of the Fed’s announcement, the relationship inverted, meaning that five-year bonds yielded more than the 10-year; the dreaded “inverted yield curve.” It was the first time this relationship had inverted since early 2007, shortly before the beginning of the credit crisis. Whenever the yield curve inverts, it tends to function as an early warning for a recession, suggesting that in the medium term rates will have to fall. Any inversion is a worrying sign, although one between five and 10 years, in the so-called “belly” of the curve, is not as alarming as an inversion between three-month or two-year yields and the 10-year yield

As Robin Brooks points out, the flattening of the yield curve results from the fact that the Fed is succeeding in hiking expectations of short-term rates, but long-term rates remain stuck.

Yield curve "bear flattening" is stymying Fed hikes. Front-end yields like 5-year (lhs, black) are rising as more hikes get priced, but back-end yields like 5y5y forward (lhs, pink) are stuck (rhs). Financial conditions aren't tightening, so how can we hope to get inflation down? pic.twitter.com/cwFtxqCvvC

— Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) March 18, 2022

The flattening of the US yield curve has at least one benign side effect. As Robin Brooks points out, the failure of US long-term yields to rise has, so far, spared the emerging markets a major taper tantrum.

How can we have a hawkish Fed meeting & yet EM rallies? The Fed is "lost in translation:" it talks about hikes, when what matters for US financial conditions are long-term yields, which remain low. As long as that's the case, US inflation will stay a problem & EM will do well… pic.twitter.com/wbFEfDgmyt

— Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) March 18, 2022

Faced with a flattening yield curve what is the Fed to do? The markets seem to believe that the most likely outcome is that it will pull back from any monetary tightening.

Ukraine will provide Powell with a further excuse to slow the increase in interest rates. But if that is the case will inflation not continue and will expectations become even more unanchored? And will that force the Fed to slam on the brakes really hard further down the line.

But, perhaps, to indulge in such dark scenarios is to concede too much to the Fed’s critics. Perhaps the best way to understand the underlying logic of Fed’s position is simply to see it as a comprehensive effort to convey one simple but important message: “no drama”.

After all, the situation is truly opaque. As as the FT remarks.

Any ceasefire or even a lasting peace deal (in Ukraine) would be disinflationary — partly reversing the increase in oil prices since the invasion began — while escalations of the violence could exacerbate the stagflationary pressure in the world economy. China’s Covid lockdowns, too, could have unforeseen effects, reducing global demand for commodities but also aggravating the problems with supply chains that have driven up prices for some manufactured goods.

One thing that the Fed does not have to fear is any serious political resistance to taking action against inflation, in the event that it has to do so. As Sonal Desai, chief investment officer at Franklin Templeton, told the FT

“It is rare for a central bank to have zero political pushback on tightening,” she said. “I think the level of conviction [of] the Fed comes from the fact that there is full, broad cross-party support for getting inflation under control because it is the single most significant issue for Americans.”

This, of course, is not merely a matter of public opinion. What has changed is the balance of social forces. There is no powerful lobby for organized labour pushing against deflation and that also means, as far as the Fed is concerned, there is no rush. It does not need to build anti-inflationary momentum. In the event that the problem is not transitory there will be agreement on doing “whatever it takes”.

Rather than chasing the shadows of the past we should recognize the situation for what it is: Something novel. Truly not a repeat of the 1970s.

*****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of readers around the world. But, what sustains the effort, are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters that keep it going, press this button and pick one of the three options:

Thanks for reading! And please share with your friends.

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

The chair of the central bank on Wednesday sought to drive home that point, framing the first interest rate rise since 2018 as the start of a series of increases and emphasising that the Federal Open Market Committee was “acutely aware of the need to return the economy to price stability and determined to use our tools to do exactly that”. Volcker’s efforts to squeeze out inflation sent the US economy into a steep recession. But Powell struck an optimistic note at a press conference on Wednesday, saying the sheer strength of the US economy meant it could “flourish” in the face of less accommodative monetary policy. Economists have welcomed Powell’s embrace of a much more aggressive policy approach, compared to the gradual pace signalled just three months ago. They warned, however, that the amount of monetary tightening potentially needed to quell inflation may produce much more economic pain than the Fed is willing to admit. “This was a big, important step in the right direction,” said Ethan Harris, head of global economics research at Bank of America. “But there could be other much less friendly steps where they basically say, ‘we’re taking away the punchbowl and we’re really going to end the party’.” Powell’s hawkish tilt was underscored by the so-called dot plot of individual interest rate projections, which showed officials expect to lift the federal funds rate to 1.9 per cent by the end of the year from the target range of 0.25 per cent to 0.50 per cent established on Wednesday — translating to six additional quarter-point increases this year. Additional rate rises pencilled in for 2023 would bring the benchmark interest rate to 2.8 per cent. That is slightly higher than the level a majority of policymakers believe will neither hasten nor hold up growth, known as the neutral rate, which they pegged at 2.4 per cent. At that pace, the majority of Fed officials forecast core inflation to moderate from 4.1 per cent by the end of 2022 to 2.6 per cent in 2023, before dropping to 2.3 per cent the year after. While economic growth is set to slow from 2.8 per cent to 2 per cent over the time period, according to the new projections, policymakers saw almost no change in the unemployment rate. Unemployment is expected to settle at 3.5 per cent this year and next before ticking up only 0.1 percentage point by 2024, despite the large increase in rates. For Peter Hooper, a nearly three-decade Fed veteran who now is global head of economic research at Deutsche Bank, the Fed’s overarching outlook amounted to “wishful thinking”. “The problem is that they need to acknowledge at some point that the economy is going to have to slow and unemployment is going to have to rise to begin to take some of this extra inflation out of the system if there’s a risk of it becoming increasingly embedded,” he said. “A lot of things have to go amazingly well for you to bring down inflation substantially.” Hooper said it is possible the fed funds rate may need to rise as much as 1 percentage point above “neutral” to roughly 3.5 per cent in order to tame price pressures. Even at the projected pace of tightening, Roberto Perli, a former Fed staffer, warned the central bank was “playing with fire”. He sees the risk of a recession rising for 2023. “The risk is that the FOMC may be too focused on bringing down inflation and willing to roll the dice with respect to growth and the labour market,” said Perli, who is now the head of global policy research at Piper Sandler. Powell on Wednesday again said the Fed would be “nimble” in its thinking about setting monetary policy, a point underscored by the wide range in central bank officials’ forecasts for the funds rate through this year, which spanned from 1.4 per cent to 3.1 per cent. Constance Hunter, global head of strategy and ESG at AIG, said the diversity of views indicates “a Fed that has a certain amount of agility with regard to how it might respond to events as they unfold for the remainder of this year”. Recommended Moral Money Biden team hits stumbling blocks in greening the US financial system Premium That may even mean reducing the pace of interest rate increases if growth slows too quickly, according to some economists, or using a policy tool the Fed has not deployed since 2000 — boosting the size of its rate increase to half a percentage point, said Jason Thomas, head of global research at Carlyle. It could also speed up the pace at which it shrinks its $9tn balance sheet. With clear signs that inflationary pressures have rippled out well beyond the pandemic-affected sectors where they began, Sonal Desai, chief investment officer at Franklin Templeton, said it is much more likely the Fed will lean in a more hawkish direction and is forced to raise interest rates much more significantly than anticipated. The political environment makes that more probable as well, she said. “It is rare for a central bank to have zero political pushback on tightening,” she said. “I think the level of conviction [of] the Fed comes from the fact that there is full, broad cross-party support for getting inflation under control, because it is the single most significant issue for Americans.”

Bond market sounds a growth alarm as curves continue to flatten. Can the Fed tighten this meaningfully without recession? Do we need a recession to dampen inflation below the Fed’s target? pic.twitter.com/IwKHhf2V04

— Valerie Tytel (@ValerieTytel) March 17, 2022

When the thought of war in Ukraine was only a dark shadow on the horizon, the chatter around the markets was all about one thing: when do the central banks tighten? How far will they have to go, to halt an acceleration of inflation? Can they pull off a tightening cycle without crash-landing the economy? Are we headed for a return of stagflation? If what is in store is not a return to the 1970s, could it be something bad and new, driven this time by an interest rate shock to over-leveraged balance sheets?

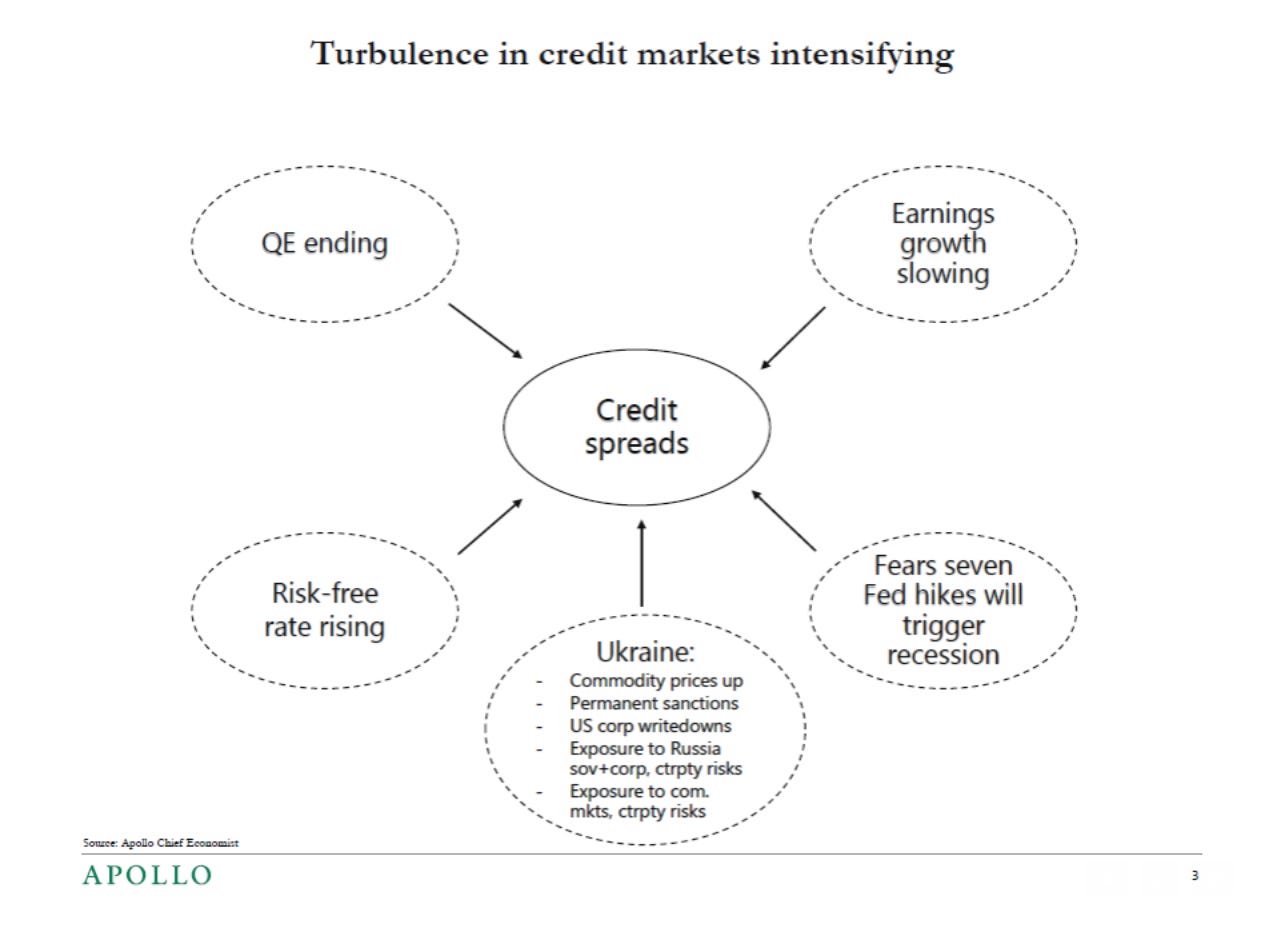

I was reminded of all this by a newsletter that came in this morning from Torsten Slok, long Chief Economist at Deutsche Bank in New York, now with Apollo. If you can get on Torsten’s mailing list, he is an essential follow. The lengthy report was put together by Slok, as Chief Economist, Jyoti Agarwal, Senior Economist and Rajvi Shah, Economist.

As this slide – reminiscent of one my Krisenbilder – shows, Torsten and his team are worried economists. And what they are worrying about is the private credit market.